Supporting Perinatal Mental Health and Wellbeing during COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rapid Critical Review of the Literature

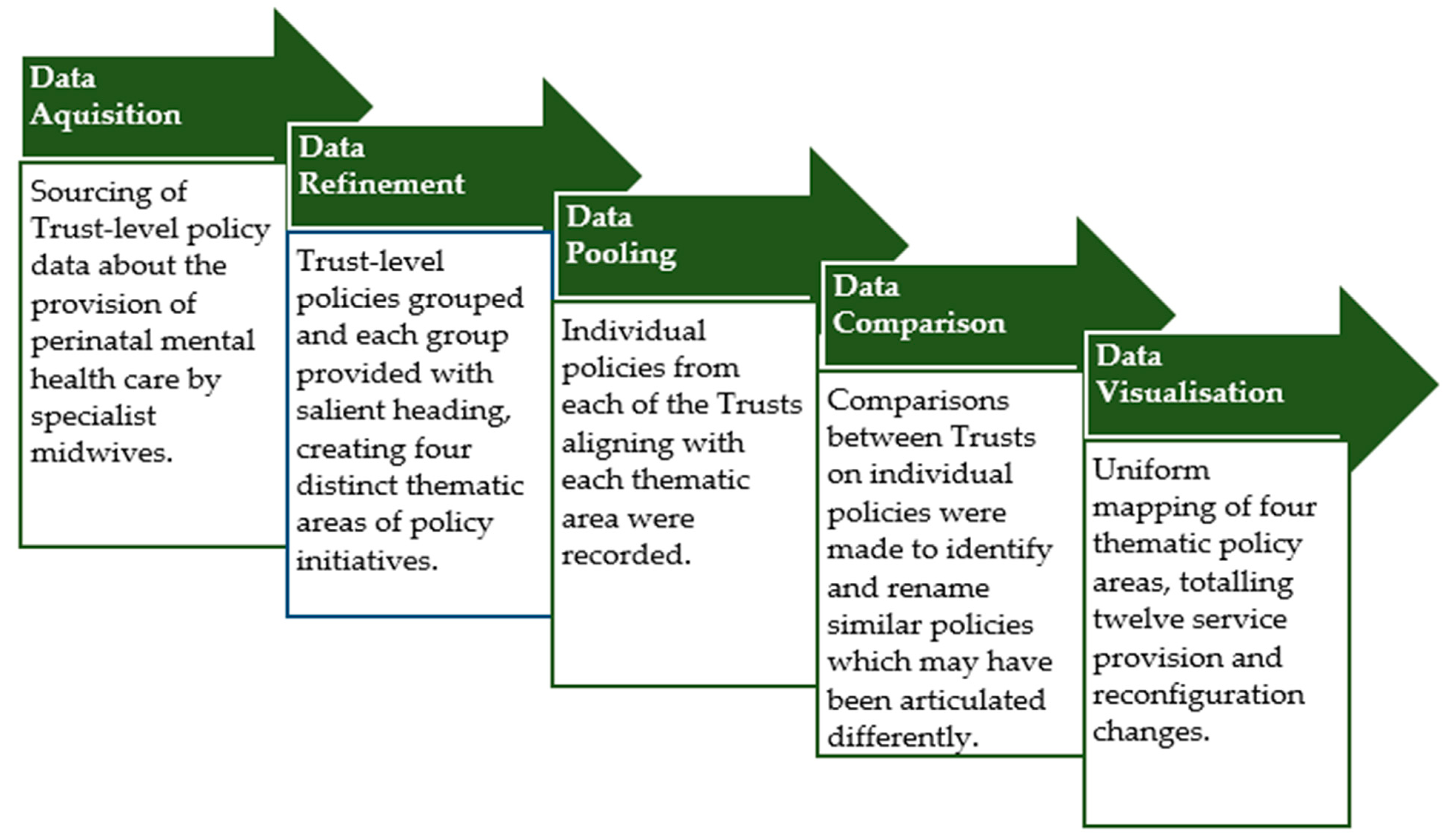

2.2. Local Knowledge Mapping Exercise

3. Results

3.1. Rapid Response to COVID-19 Pandemic Critical Review of the Literature

3.1.1. Increased Perinatal Distress

3.1.2. Inaccessible Services and Support

3.2. Knowledge Mapping Exercise

3.2.1. Retention of Existing Service Provision

3.2.2. Additional Services Provided

3.2.3. Reconfiguration of Service Provision

3.2.4. Additional Provision to Support Staff Wellbeing

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

4.2. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, L. Falling through the Gaps: Perinatal Mental Health and General Practice; Centre for Mental Health: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/falling-through-gaps (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Papworth, R.; Harris, A.; Durcan, G.; Wilton, J.; Sinclair, C. Maternal Mental Health during a Pandemic: A Rapid Evidence Review of Covid-19’s Impact. 2021. Available online: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/maternal-mental-health-during-pandemic (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Watson, H.; Harrop, D.; Walton, E.; Young, A.; Soltani, H. A systematic review of ethnic minority women’s experiences of perinatal mental health conditions and services in Europe. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.; Ryan, E.; Trevillion, K.; Anderson, F.; Bick, D.; Bye, A.; Byford, S.; O’Connor, S.; Sands, P.; Demilew, J.; et al. Accuracy of the Whooley questions and the EPDS in identifying depression and other mental disorders in early pregnancy. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2018, 212, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.M.; Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Psychiatry, T.L. Isolation and inclusion. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020, 5, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, J.; Relph, S.; Magee, L.A.; von Dadelszen, P.; Morris, E.; Ross-Davie, M.; Draycott, T.; Khalil, A. Maternity services in the UK during the coronavirus disease 2019 Pandemic: A national survey of modifications to standard care. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Midwives and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Pregnancy. 2021. Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/coronavirus-pregnancy (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Adhanom Ghebreyesus, T. Addressing mental health needs: An integral part of COVID-19 response. World Psychiatr. 2020, 19, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matvienko-Sikar, K.; Meedya, S.; Ravaldi, C. Perinatal mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women Birth 2020, 33, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midwives, Royal College of London. Specialist Mental Health Midwives: Why They Matter; Royal College of Midwives: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silverio, S.A. Women’s mental health a public health priority: A call for action. J. Public Ment. Health 2020, 20, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebener, S.; Khan, A.; Shademani, R.; Compernolle, L.; Beltran, M.; Lansang, M.A.; Lippman, M. Knowledge mapping as a technique to support knowledge translation. Bull. World Health Organ. 2006, 84, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, G.; Knighting, K.; Bray, L. The specification, acceptability and effectiveness of respite care and short breaks for young adults with complex healthcare needs: Protocol for a mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata-Delgado, A.; Perinatal Distress: Early Screening and Management. PHN Central and Eastern Sydney. 2021. Available online: https://www.cesphn.org.au/news/latest-updates/57-enews/2425-perinatal-distress-early-screening-and-management (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Motrico, E.; Mateus, V.; Bina, R.; Felice, E.; Bramante, A.; Kalcev, G. Good practices in perinatal mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A report from task-force RISEUP-PPD COVID-19. Clínica Salud. 2020, 31, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. Perinatal mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatr. 2020, 19, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, B.; Garad, R.; Boyle, J.; Skouteris, H.; Teede, H.; Harrison, C. Perinatal Distress during COVID-19: Thematic Analysis of an Online Parenting Forum. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2021, 22, e22002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotlar, B.; Gerson, E.; Petrillo, S.; Langer, A.; Tiemeier, H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: A scoping review. Reprod. Health, 18, 1–39.

- The Guardian. Most New and Expectant Mothers Feel More Anxious Due to Covid, Finds Survey. 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/jan/01/most-new-and-expectant-mothers-feel-more-anxious-due-to-covid-finds-surve (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Best Beginnings, Home-Start UK, Parent-Infant Foundation. Babies in Lockdown: Listening to Parents to Build Back Better; Parent-Infant Foundation: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hessami, K.; Romanelli, C.; Chiurazzi, M.; Cozzolino, M. COVID-19 pandemic and maternal mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 21, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.; Parish, N.; Working for Babies. Lockdown Lessons from Local Systems. First 1001 Days Movement. 2021. Available online: https://parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/210121-F1001D_Working_for_Babies_v1.2-FINAL-compressed_2.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Basu, A.; Kim, H.H.; Basaldua, R.; Choi, K.W.; Charron, L.; Kelsall, N. A cross-national study of factors associated with women’s perinatal mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambrook Smith, M.; Lawrence, V.; Sadler, E.; Easter, A. Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: Systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptie, G.; Baddelley, A.; Smith, J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Women’s Maternity Choices. 2021. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1UyzRKrQHvxhRcTlRA8mhy8CyJ7FV_PNU/view (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020, 41, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Dalton-Locke, C.; Johnson, S.; Simpson, A.; Oram, S.; Howard, L. Challenges and opportunities of the COVID-19 pandemic for perinatal mental health care: A mixed methods study of mental health care staff. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health. 2020, 24, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.; Bunch, K.; Cairns, A.; Cantwell, R.; Cox, P.; Kenyon, S.; Kotnis, R.; Luca, N.; Lucas, S.; Marshall, L.; et al. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care Rapid Report: Learning from SARS-CoV2-Related and Associated Maternal Deaths in the UK March–May 2020; Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership and National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Romanis, E.C.; Nelson, A. Homebirthing in the United Kingdom during COVID-19. Med. Law Int. 2020, 20, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimstad, R.; Dahloe, R.; Laache, I.; Skogvoll, E.; Schei, B. Fear of childbirth and history of abuse: Implications for pregnancy and delivery. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2006, 85, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham-Harrison, E.; Giuffrida, A.; Smith, H.; Ford, L. Lockdowns around the World Bring Rise in Domestic Violence. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Childcare, Covid and Career: The True Scale of the Crisis Facing Working Mums. 2020. Available online: https://pregnantthenscrewed.com/the-covidcrisis-effect-on-working-mums/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Knight, M.; Bunch, K.; Cairns, A.; Cantwell, R.; Cox, P.; Kenyon, S.; Kotnis, R.; Lucas, D.N.; Lucas, S.; Nelson-Piercy, C.; et al. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care Rapid Report 2021: Learning from SARS-CoV-2-Related and Associated Maternal Deaths in the UK June 2020–March 2021; National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Midwives; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in Pregnancy: Information for Healthcare Professionals. 2021. Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/coronavirus-covid-19-pregnancy-and-womenshealth/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Silverio, S.A.; De Backer, K.; Easter, A.; von Dadelszen, P.; Magee, L.A.; Sandall, J. Women’s experiences of maternity service reconfiguration during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative investigation. Midwifery 2021, 102, 103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon, V.; Davies, S.M.; Silverio, S.A.; Jackson, L.; De Pascalis, L.; Harrold, J.A. Psychosocial experiences of postnatal women during the COVID-19 pandemic. A UK-wide study of prevalence rates and risk factors for clinically relevant depression and anxiety. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Silverio, S.A.; Davies, S.M.; Christiansen, P.; Aparicio-García, M.E.; Bramante, A.; Cheng, P.; Costas-Ramón, N.; de Weerth, C.; Della Vedova, A.M.; Infante Gil, L.; et al. A validation of the Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale 12-item research short-form for use during global crises with five translations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.; De Pascalis, L.; Harrold, J.A.; Fallon, V.; Silverio, S.A. Postpartum women’s psychological experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A modified recurrent cross-sectional thematic analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverio, S.A.; Easter, A.; Storey, C.; Jurković, D.; Sandall, J. Preliminary findings on the experiences of care for parents who suffered perinatal bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 840, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.; De Pascalis, L.; Harrold, J.A.; Fallon, V.; Silverio, S.A. Postpartum women’s experiences of social and healthcare professional support during the COVID-19 pandemic: A recurrent cross-sectional thematic analysis. Women Birth 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, N.H.S. Implementing Better Births: Continuity of Carer; NHS: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Turienzo, C.; Newburn, M.; Agyepong, A.; Buabeng, R.; Dignam, A.; Abe, C.; Bedward, L.; Rayment-Jones, H.; Silverio, S.A.; Easter, A.; et al. Addressing inequities in maternal health among women living in communities of social disadvantage and ethnic diversity. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Service Provisions and Reconfigurations | Trust A | Trust B | Trust C | Trust D | Trust E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention of Existing Service Provision | Continuation of face-to-face appointments for women with a current diagnosis of mental illness |  |  |  |  |  |

| Perinatal Mental Health Midwives working alongside Caseloading Midwives |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Additional Services Provided | Additional support provided (to meet increased reporting of perinatal anxiety) |  |  |  |  |  |

| Provision of co-developed resource offering virtual support for women and/or families |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Provision of ‘Birth Without Fear’ class to meet rise in elective caesarean section requests |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Increased Perinatal Mental Health Midwife staffing to meet demand on service |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Reconfiguration of Service Provision | Face-to-face exercise classes moved to on-line provision |  |  |  |  |  |

| Art psychotherapy moved to online provision |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Virtual antenatal clinics offering continuity of (midwife) carer |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Provision of support for partner/parent to accompany woman/birthing person in exceptional circumstances only |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Provision of virtual appointments for those unable or not wanting to attend face-to-face |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Additional Provision to Support Staff Wellbeing | In-house support for staff mental wellbeing |  |  |  |  |  |

= yes: continuation of service provision;

= yes: continuation of service provision;  = yes: addition of service provision;

= yes: addition of service provision;  = no;

= no;  = not applicable.

= not applicable.Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bridle, L.; Walton, L.; van der Vord, T.; Adebayo, O.; Hall, S.; Finlayson, E.; Easter, A.; Silverio, S.A. Supporting Perinatal Mental Health and Wellbeing during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031777

Bridle L, Walton L, van der Vord T, Adebayo O, Hall S, Finlayson E, Easter A, Silverio SA. Supporting Perinatal Mental Health and Wellbeing during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031777

Chicago/Turabian StyleBridle, Laura, Laura Walton, Tessa van der Vord, Olawunmi Adebayo, Suzy Hall, Emma Finlayson, Abigail Easter, and Sergio A. Silverio. 2022. "Supporting Perinatal Mental Health and Wellbeing during COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031777

APA StyleBridle, L., Walton, L., van der Vord, T., Adebayo, O., Hall, S., Finlayson, E., Easter, A., & Silverio, S. A. (2022). Supporting Perinatal Mental Health and Wellbeing during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031777