The Development of a Model to Predict Sports Participation among College Students in Central China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

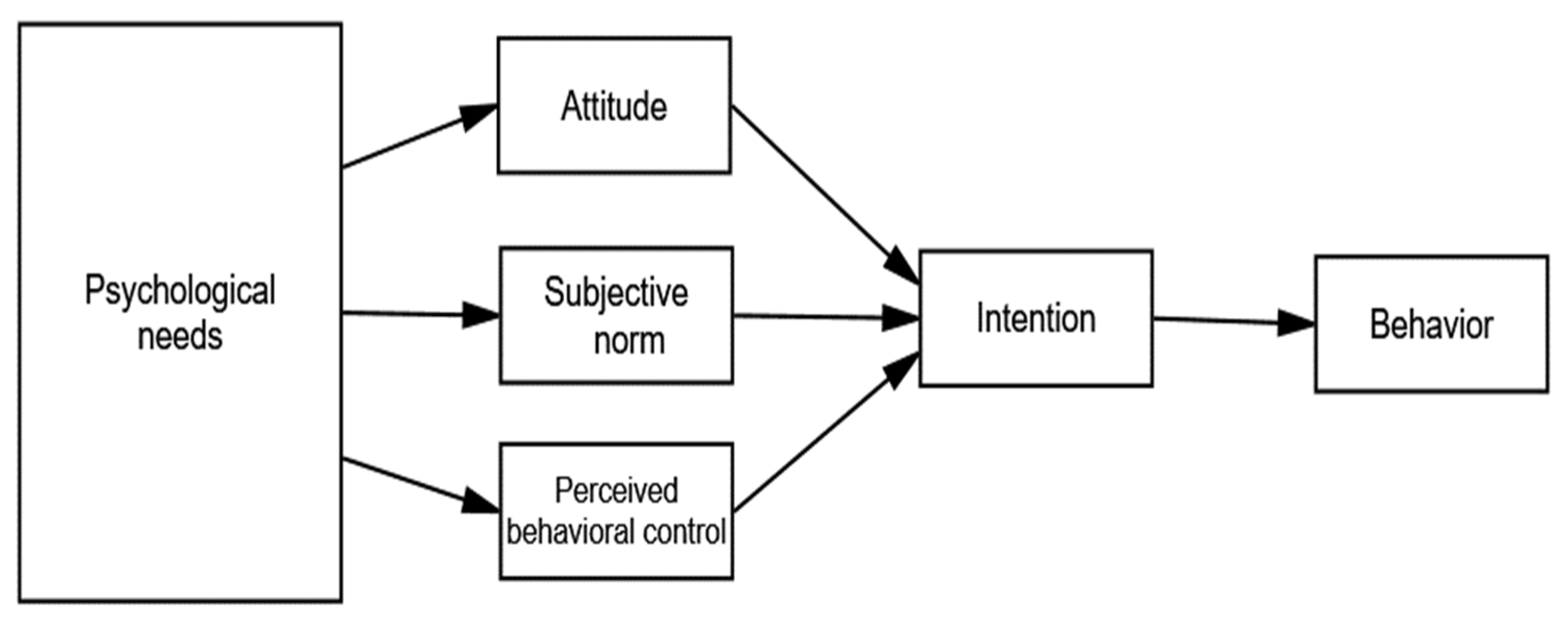

1.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

1.2. Self-Determination Theory

1.3. Aim of the Present Study

- When integrating SDT and the TPB, how do the basic psychological needs from SDT enhance sports participation and exercise intentions?

- What intermediary roles do the TPB’s three factors play in the relationship between sports participation and basic psychological needs?

2. Methodology

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Model Fit and Direct Effects

3.2. Indirect Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouchard, C.; Shephard, R.J.; Stephens, T.E. (Eds.) Physical activity, fitness, and health: International proceedings and consensus statement. In Proceedings of the International Consensus Symposium on Physical Activity, Fitness, and Health, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2 May 1992; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Fish, C.; Nies, M.A. Health promotion needs of students in a college environment. Public Health Nurs. 1996, 13, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z. The Research on the Extracurricular Physical Exercise Current Situation and Countermeasures of College Student in Hubei Province; Huazhong University of Science and Technology: Wuhan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dinger, M.K.; Brittain, D.R.; Hutchinson, S.R. Associations between physical activity and health-related factors in a national sample of college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, D.E.; Wilson, P.M.; Lightheart, V.; Oster, K.; Gunnell, K.E. Healthy Campus 2010: Physical activity trends and the role information provision. J. Phys. Act. Health 2009, 6, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; Nelson, M.C.; Popkin, B.M. Longitudinal physical activity and sedentary behavior trends: Adolescence to adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparling, P.B.; Snow, T.K. Physical activity patterns in recent college alumni. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2002, 73, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J. Can the theory of planned behavior predict the maintenance of physical activity? Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grol, R.P.; Bosch, M.C.; Hulscher, M.E.; Eccles, M.P.; Wensing, M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 93–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. (Eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Sparks, P. Theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour. Predict. Health Behav. 2005, 2, 121–162. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, H.; Paulussen, T.; Schaalma, H. Physical exercise habit: On the conceptualization and formation of habitual health behaviours. Health Educ. Res. 1997, 12, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chan, D.K.C.; Protogerou, C.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Using meta-analytic path analysis to test theoretical predictions in health behavior: An illustration based on meta-analyses of the theory of planned behavior. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Harris, J. From psychological need satisfaction to intentional behavior: Testing a motivational sequence in two behavioral contexts. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 32, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.D.L. Integrating the theory of planned behaviour and self-determination theory in health behaviour: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jubari, I.; Arif, H.; Liñán, F. Entrepreneurial intention among University students in Malaysia: Integrating self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1323–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Hagger, M.S.; Smith, B. Influences of perceived autonomy support on physical activity within the theory of planned behavior. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 934–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.M.; Chen, S.; Carter, C. Fundamental human needs: Making social cognition relevant. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Standage, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. A model of contextual motivation in physical education: Using constructs from self-determination and achievement goal theories to predict physical activity intentions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.M.; Rodgers, W.M. The relationship between perceived autonomy support, exercise regulations and behavioral intentions in women. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Personal. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Flaste, R. Why We Do What We Do: The Dynamics of Personal Autonomy; GP Putnam’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Silva, M.N.; Mata, J.; Palmeira, A.L.; Markland, D. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. Handb. Self-Determ. Res. 2002, 2, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, P.M.; Mack, D.E.; Grattan, K.P. Understanding motivation for exercise: A self-determination theory perspective. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Meek, G.A. A self-determination theory approach to the study of intentions and the intention–behaviour relationship in children’s physical activity. Br. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Biddle, S.J.H. Functional significance of psychological variables that are included in the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Self-Determination Theory approach to the study of attitudes, subjective norms, perceptions of control and intentions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Hagger, M.S.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Karageorghis, C. The cognitive processes by which perceived locus of causality predicts participation in physical activity. J. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Biddle, S.J.H. The influence of autonomous and controlling motives on physical activity intentions within the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D. Structural equations modeling: Fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. 2006. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235913732_Constructing_a_Theory_of_Planned_Behavior_Questionnaire (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. (2002): 2013. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.601.956&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Shen, M.; Mao, Z.; Yimin, Z. Intervention strategies of Chinese Adult’s Exercise Behavior: The Integration of the TPB with the HAPA. China Sport Sci. 2010, 12, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, P.M.; Rogers, W.T.; Rogers, W.M.; Wild, T.C. The psychological need satisfaction in exercise scale. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P. Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Stine, R.A. Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.M.; MacKinnon, D.P. Bootstrapping the standard error of the mediated effect. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting of SAS Users Group International, Nashville, TN, USA, 22–25 March 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blue, C.L. The predictive capacity of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior in exercise research: An integrated literature review. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Biddle, S. A meta-analytic review of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior in physical activity: Predictive validity and the contribution of additional variables. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.D.L.; Culverhouse, T.; Biddle, S. The processes by which perceived autonomy support in physical education promotes leisure-time physical activity intentions and behavior: A trans-contextual model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noar, S.M.; Zimmerman, R.S. Health behavior theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: Are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ. Res. 2005, 20, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beville, J.M.; Meyer, M.R.U.; Usdan, S.L.; Turner, L.W.; Jackson, J.C.; Lian, B.E. Gender differences in college leisure time physical activity: Application of the theory of planned behavior and integrated behavioral model. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-U.; Lee, C.G.; Kim, D.-K.; Park, J.-H.; Jang, D.-J. A Developmental Model for Predicting Sport Participation among Female Korean College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachan, R.R.C.; Conner, M.; Taylor, N.J.; Lawton, R.J. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 97–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G. The theories of reasoned action and planned behavior: Overview of findings, emerging research problems and usefulness for exercise promotion. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1993, 5, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L.; Carlsmith, J.M. Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1959, 58, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A. Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: A role for group identification. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 22, 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A.; White, K.M. The theory of planned behaviour: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 38, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number (Persons) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Males | 144 | 49.00 |

| Females | 150 | 51.00 | |

| Age | 18 | 8 | 2.72 |

| 19 | 13 | 4.42 | |

| 20 | 45 | 15.31 | |

| 21 | 42 | 14.29 | |

| 22 | 59 | 20.07 | |

| 23 | 63 | 21.43 | |

| 24 | 33 | 11.22 | |

| 25 | 27 | 9.18 | |

| 26 | 3 | 1.02 | |

| 27 | 1 | 0.34 | |

| College year | Freshman | 80 | 27.21 |

| Sophomore | 62 | 21.09 | |

| Junior | 77 | 26.19 | |

| Senior | 75 | 25.51 | |

| Sport | Jogging | 170 | 57.82 |

| Team sport | 34 | 11.57 | |

| Dancing | 35 | 11.91 | |

| Aerobic activity | 17 | 5.78 | |

| Walking | 10 | 3.40 | |

| Other | 28 | 9.52 | |

| Per week | No | 6 | 2.04 |

| 1–2 times | 124 | 42.18 | |

| 3–4 times | 93 | 31.63 | |

| 5–6 times | 50 | 17.01 | |

| 7 times | 21 | 7.14 | |

| Time per exercise | Less than 10 min | 20 | 6.80 |

| 11–20 min | 111 | 37.75 | |

| 21–30 min | 71 | 24.15 | |

| 31–60 min | 54 | 18.37 | |

| 60 min or more | 38 | 12.93 | |

| Habits | Less than 1 months | 64 | 21.77 |

| 1–3 months | 130 | 44.22 | |

| 3–6 months | 46 | 15.65 | |

| 6 months–1 year | 21 | 7.14 | |

| More than 1 year | 33 | 11.22 | |

| Path (Direct Effects) | Parameter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Std. | |

| COM → ATT | 0.313 | 0.07 | 4.476 | *** | 0.311 |

| COM → SUB | 0.146 | 0.063 | 2.299 | 0.022 | 0.168 |

| COM → PBC | 0.397 | 0.072 | 5.495 | *** | 0.401 |

| AUT → ATT | 0.203 | 0.091 | 2.238 | 0.025 | 0.162 |

| AUT → SUB | 0.026 | 0.082 | 0.315 | 0.753 | 0.024 |

| REL → SUB | 0.357 | 0.076 | 4.701 | *** | 0.353 |

| AUT → PBC | 0.077 | 0.093 | 0.827 | 0.408 | 0.062 |

| REL → PBC | 0.104 | 0.083 | 1.263 | 0.207 | 0.091 |

| REL → ATT | 0.215 | 0.08 | 2.678 | 0.007 | 0.184 |

| ATT → INT | 0.295 | 0.047 | 6.301 | *** | 0.543 |

| SUB → INT | 0.018 | 0.05 | 0.362 | 0.718 | 0.029 |

| PBC → INT | 0.352 | 0.052 | 6.789 | *** | 0.636 |

| INT → SP | 0.253 | 0.063 | 4.012 | *** | 0.310 |

| Indirect Effects | Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency | Attitude | Intention | Sport participation | 0.022 (***) |

| Subjective norm | Intention | Sport participation | 0.003 (*) | |

| Perceived behavioral control | Intention | Sport participation | 0.031 (***) | |

| Relatedness | Attitude | Intention | Sport participation | 0.014 (*) |

| Subjective norm | Intention | Sport participation | 0.001 | |

| Perceived behavioral control | Intention | Sport participation | 0.006 | |

| Autonomy | Attitude | Intention | Sport participation | 0.015 (***) |

| Subjective norm | Intention | Sport participation | 0.007 (*) | |

| Perceived behavioral control | Intention | Sport participation | 0.008 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, T.; Tang, S.; Shim, Y. The Development of a Model to Predict Sports Participation among College Students in Central China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031806

Liao T, Tang S, Shim Y. The Development of a Model to Predict Sports Participation among College Students in Central China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031806

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Tianzhi, Saizhao Tang, and Yunsik Shim. 2022. "The Development of a Model to Predict Sports Participation among College Students in Central China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031806

APA StyleLiao, T., Tang, S., & Shim, Y. (2022). The Development of a Model to Predict Sports Participation among College Students in Central China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031806