Conflict Sources and Management in the ICU Setting before and during COVID-19: A Scoping Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Methods

2.3. Study Selection

- Year of publication: 2015–2021 (the researchers focused on the latest studies, hence the years of publication);

- Studies carried out in intensive care units for adults;

- Publication type (original papers only).

- Year of publication earlier than 2015;

- Studies carried out in departments other than ICUs;

- Articles concerning neonatal and paediatric intensive care units;

- Publication type (articles with research examples, letters to the editor, meta-analyses, review papers).

2.4. Research Variables and Strategy

2.5. Methodological Quality and Level of Evidence

2.6. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

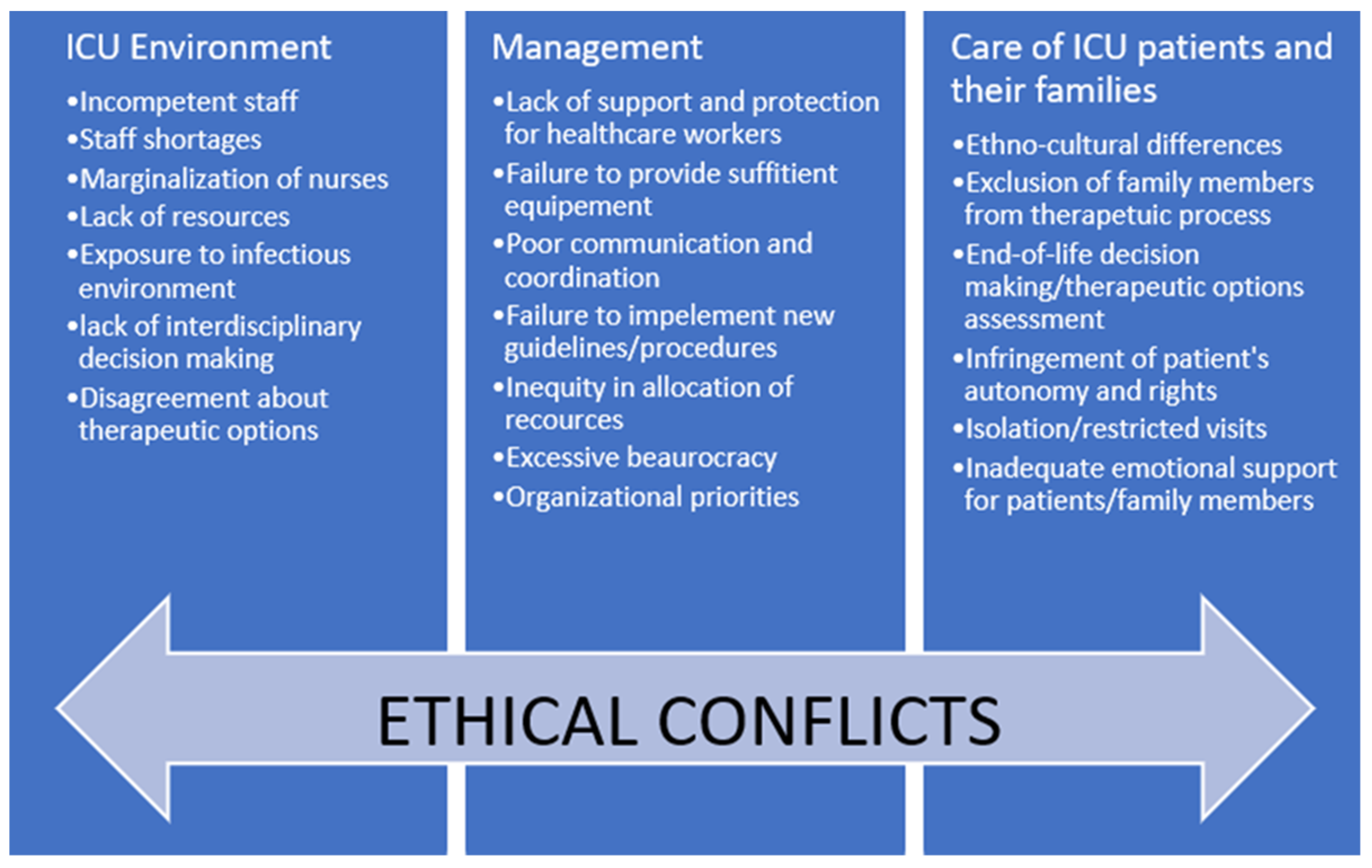

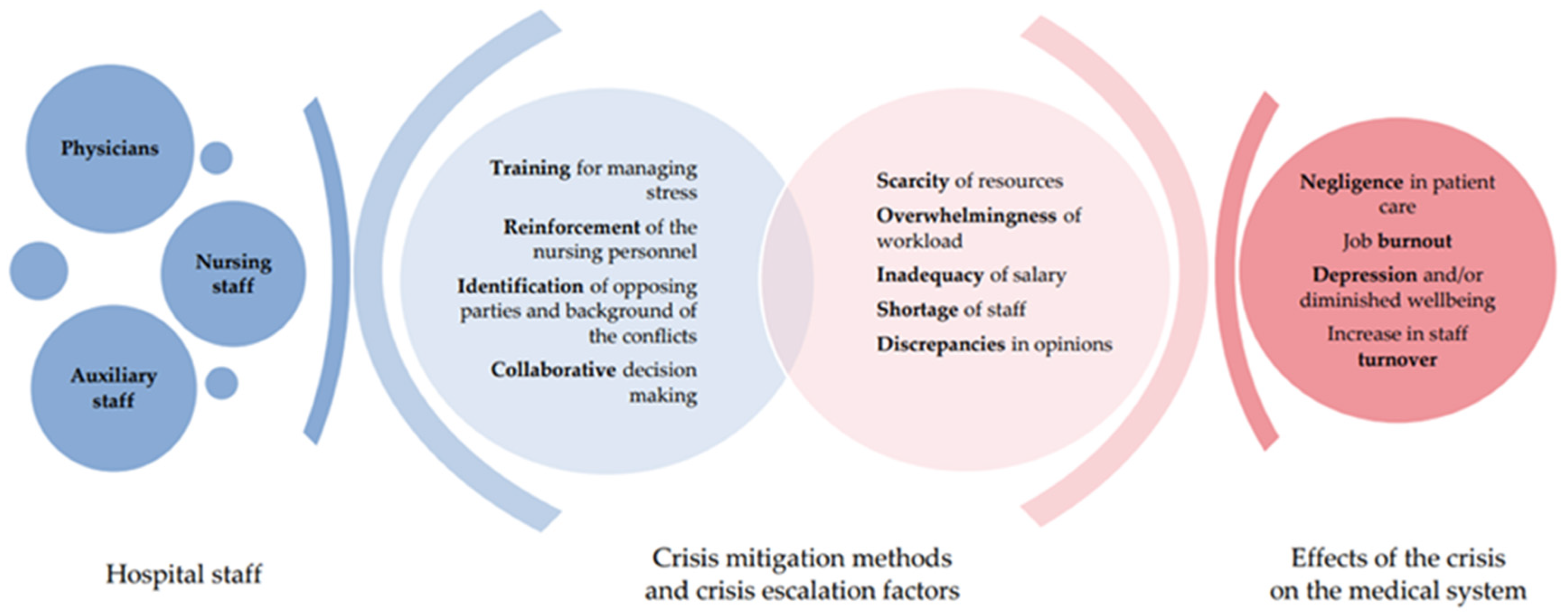

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications for Practice

- identification of opposing parties;

- identification of the background of the conflict;

- provide a time and place for the analysis and debate of conflictive situations;

- personnel training on interpersonal communication;

- training on managing stress and relieving emotions, e.g., debriefing;

- training for managing personnel in conflict management;

- reinforcement of nursing personnel in reaching a consensus on the suggested therapy;

- more accessible psychological support;

- clear vision and feedback from management;

- shared decision making;

- improving the implementation of new guidelines and orders.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wujtewicz, M.; Wujtewicz, M.A.; Owczuk, R. Konflikty na oddziale anestezjologii i intensywnej terapii. Anaesthesiol. Intensiv. Ther. 2015, 47, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingart, L.R.; Behfar, K.J.; Bendersky, C.; Todorova, G.; Jehn, K.A. The Directness and Oppositional Intensity of Conflict Expression. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarchiaro, J.; White, D.B.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Buddadhumaruk, P.; Schuster, R.A.; Arnold, R.M. Conflict Management Strategies in the ICU Differ Between Palliative Care Specialists and Intensivists. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbat, L.; Mnatzaganian, G.; Barclay, S. The Healthcare Conflict Scale: Development, validation and reliability testing of a tool for use across clinical settings. J. Interprof. Care 2019, 33, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embriaco, N.; Azoulay, E.; Barrau, K.; Kentish, N.; Pochard, F.; Loundou, A.; Papazian, L. High Level of Burnout in Intensivists. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, J.B.; Cohen, T.R.; White, U.B. Reducing the Stress on Clinicians Working in the ICU. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 320, 1981–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Hajiesmaeili, M.; Kangasniemi, M.; Fornés-Vives, J.; Hunsucker, R.L.; Rahimibashar, F.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Farrokhvar, L.; Miller, A. Effects of Stress on Critical Care Nurses: A National Cross-Sectional Study. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2017, 34, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.Y.; Kim, J.-O. Ethics in the Intensive Care Unit. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2015, 78, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pattison, N. End-of-life decisions and care in the midst of a global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Intensiv. Crit. Care Nurs. 2020, 58, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlster, S.; Sharma, M.; Lewis, A.K.; Patel, P.V.; Hartog, C.S.; Jannotta, G.; Blissitt, P.; Kross, E.K.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Greer, D.M.; et al. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic’s Effect on Critical Care Resources and Health-Care Providers. Chest 2021, 159, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, R.; Kentish-Barnes, N.; Boyer, A.; Laurent, A.; Azoulay, E.; Reignier, J. Ethical dilemmas due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, L. Interprofessional collaboration in the ICU: How to define? Nurs. Crit. Care 2011, 16, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kłusek, B. Five Styles of Conflict Resolution: A Questionnaire. Czas Psychol. Available online: http://www.czasopismopsychologiczne.pl/files/articles/2009-15-kwestionariusz-stylw-rozwizywania-konfliktw.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Klusek-Wojciszke, B. Personality Antecedents of Conflict Resolution Styles (Osobowosc jako Determinanta Wyboru Stylu Rozwiazywania Konfliktów). Available online: http://bazekon.icm.edu.pl/bazekon/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000164805565 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Saryusz-Wolska, H.; Adamus-Matuszyńska, A. Conflicts and Their Solutions in Healthcare Organization. Available online: File:///C:/Users/Gumed/AppData/Local/Temp/ZZL(HRM)_2-2011_Saryusz-Wolska_H_Adamus-Matuszynska_A_86-104-1.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Johansen, M.L.; Cadmus, E. Conflict management style, supportive work environments and the experience of work stress in emergency nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI Man. Evid. Synth. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Falcó-Pegueroles, A.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Roldan-Merino, J.; Goberna-Tricas, J.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J. Ethical conflict in critical care nursing. Nurs. Ethic 2014, 22, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishgooie, A.H.; Barkhordari_Sharifabad, M.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F.; Falcó-Pegueroles, A. Ethical conflict among nurses working in the intensive care units. Nurs. Ethic. 2018, 26, 2225–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, Z.; Shahriari, M.; Yazdannik, A.R. The relationship between ethical conflict and nurses’ personal and organisational characteristics. Nurs. Ethic. 2018, 26, 2427–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAndrew, N.S.; Hardin, J. Giving nurses a voice during ethical conflict in the ICU. Nurs. Ethic. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, C.R.; Miller, S.M.; Zimmerman, J.L. A Qualitative Study Exploring Moral Distress in the ICU Team. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramathuba, D.U.; Ndou, H.; Ramathuba, N.H. Ethical conflicts experienced by intensive care unit health professionals in a regional hospital, Limpopo province, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid 2020, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paprocka-Lipińska, A.; Drozd-Garbacewicz, M.; Erenc, J.; Wujtewicz, M.; Suchorzewska, J.; Olejniczak, M.; Wujtewicz, M.; Aszkiełowicz, H.; Dończyk, A.; Furmanik, J.; et al. Potential sources of conflict in intensive care units—a questionnaire study. Anaesthesiol. Intensiv. Ther. 2019, 51, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Keer, R.-L.; Deschepper, R.; Francke, A.L.; Huyghens, L.; Bilsen, J. Conflicts between healthcare professionals and families of a multi-ethnic patient population during critical care: An ethnographic study. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castillo, R.; González-Caro, M.; Fernández-García, E.; Porcel-Gálvez, A.; Garnacho-Montero, J. Intensive care nurses’ experiences during the COVID -19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Chen, O.; Xiao, Z.; Xiao, J.; Bian, J.; Jia, H. Nurses’ ethical challenges caring for people with COVID-19: A qualitative study. Nurs. Ethic. 2021, 28, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, J.M.; Magbee, T.; Yoder, L.H. The experiences of critical care nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 during the 2020 pandemic: A qualitative study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2021, 59, 151418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Wu, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhu, P.; Waidley, E. Ethical dilemmas faced by frontline support nurses fighting COVID-19. Nurs. Ethic. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkers, M.A.; Gilissen, V.J.H.S.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; van Dijk, N.M.; Kling, H.; Heijnen-Panis, R.; Pragt, E.; van der Horst, I.; Pronk, S.A.; van Mook, W.N.K.A. Moral distress and ethical climate in intensive care medicine during COVID-19: A nationwide study. BMC Med. Ethic. 2021, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcó-Pegueroles, A.; Zuriguel-Pérez, E.; Via-Clavero, G.; Bosch-Alcaraz, A.; Bonetti, L. Ethical conflict during COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Spanish and Italian intensive care units. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almost, J.; Wolff, A.C.; Stewart-Pyne, A.; McCormick, L.G.; Strachan, D.; D’Souza, C. Managing and mitigating conflict in healthcare teams: An integrative review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 1490–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, R.A.; Hong, S.Y.; Arnold, R.M.; White, D.B. Investigating Conflict in ICUs—Is the Clinicians’ Perspective Enough? Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecanac, K.; Schwarze, M.L. Conflict in the intensive care unit: Nursing advocacy and surgical agency. Nurs. Ethic. 2018, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fant, C. Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing. Available online: https://www.nursetogether.com/Career/Career-Article/itemid/2520.aspx (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Shaffer, F.A.; Curtin, L. What Can Employers Do to Increase Nurse Retention? Available online: https://www.myamericannurse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/an8-Turnover-728.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Bartholomew, K. Managing RN/RN and RN/MD Conflict in the ICU: Productive Ways of Communicating. Available online: https://healthmanagement.org/c/icu/issuearticle/managing-rn-rn-and-rn-md-conflict-in-the-icu-productive-ways-of-communicating (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Azoulay, E.; De Waele, J.; Ferrer, R.; Staudinger, T.; Borkowska, M.; Povoa, P.; Iliopoulou, K.; Artigas, A.; Schaller, S.J.; Hari, M.S.; et al. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azoulay, E.; Pochard, F.; Reignier, J.; Argaud, L.; Bruneel, F.; Courbon, P.; Cariou, A.; Klouche, K.; Labbé, V.; Barbier, F.; et al. Symptoms of Mental Health Disorders in Critical Care Physicians Facing the Second COVID-19 Wave. Chest 2021, 160, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data Base | Search Strings | Search Period | Obtained Articles | Articles Meeting Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBSCO | (conflicts) AND (nurses OR physicians) AND (intensive care unit OR ICU) AND (conflict management) | 2015–2020 | 225 | 4 |

| Ovid | 2015–2020 | 42 | 2 | |

| PubMed | 2015–2020 | 137 | 0 | |

| Web of Science | 2015–2020 | 16 | 2 | |

| ProQuest | 2015–2020 | 3172 | 0 | |

| Cochrane | 2015–2020 | 3 | 0 | |

| PubMed | (conflicts OR ethical conflicts OR ethical dilemmas OR ethical challenges) AND (nurses OR physicians OR medical staff) AND (intensive care unit OR ICU) AND (pandemic OR COVID-19) AND (conflict management) | 2020–2021 | 411 | 7 |

| Total | 2015–2021 | 4001 | 15 |

| Author/Date | Participants | Research Instrument | Conflict Type | Quality Assessment JBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wahlster, S. et al., 2021 [10] | 2700 respondents (physicians, nurses, RTs, APPs) | Structured questionnaire | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Falcó-Pegueroles, A. et al., 2015 [18] | 203 nurses | Ethical Conflict in Nursing Questionnaire–Critical Care Version | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Pishgooie, A.H. et al., 2018 [19] | 382 ICU nurses | Ethical Conflict in Nursing Questionnaire–Critical Care Version | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Saberi, Z. et al., 2018 [20] | 216 critical care nurses | Ethical Conflict in Nursing Questionnaire–Critical Care Version | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| McAndrew, N.S. et al., 2020 [21] | 111 ICU nurses | Open-ended questions | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Bruce, C.R. et al., 2015 [22] | 29 participants (ICU and auxiliary staff) | Interview | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Ramathuba, D.U. et al., 2020 [23] | 17 healthcare professionals | Unstructured interview | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Paprocka-Lipińska, A. et al., 2019 [24] | 232 (nurses and physicians) | Original questionnaire | Various conflicts | Include |

| Van Keer, R.L. et al., 2015 [25] | ICU staff (92) and 10 patients’ relatives | Ethnographic study (descriptive) | Various conflicts | Include |

| Fernández-Castillo, R.J. et al., 2021 [26] | 17 ICU nurses | Semi-structured interviews | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Jia, Y. et al., 2021 [27] | 18 nurses caring for COVID-19 patients | Interview | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Gordon, J.M. et al., 2021 [28] | 11 nurses from one ICU | Semi-structured interviews | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Liu, X. et al., 2021 [29] | 10 nurses, post-deployment to Wuhan | Semi-structured interviews | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Donkers, M.A. et al.,2021 [30] | 488 ICU Staff (nurses, intensivists, supporting staff) | Measurement of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) and Ethical Decision-Making Climate Questionnaire (EDMCQ) | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Falcó-Pegueroles, A. et al., 2021 [31] | Working group (5 experts) | A nominal group technique | Ethical conflicts | Include |

| Author/Date | Country | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Wahlster, S. et al., 2021 [10] | United Sates of America | Emotional distress or burnout was high across regions and associated with

|

| Falcó-Pegueroles, A. et al., 2015 [18] | Spain | Moral distress was caused by:

|

| Pishgooie, A.H. et al., 2018 [19] | Spain | Ethical conflicts occurred mostly when:

|

| Saberi, Z. et al., 2018 [20] | Iran | Ethical conflicts mostly occurred when working with incompetent physicians/nurses/nurses assistants; high exposure to ethical conflict appeared within poor organizational culture and management. |

| McAndrew, N.S. et al., 2020 [21] | United States of America | Ethical dilemmas were a result of:

|

| Bruce, C.R. et al., 2015 [22] | United States of America | Moral distress occurred in situations:

|

| Paprocka-Lipińska, A. et al., 2019 [24] | Poland | Most common conflicts concerned:

|

| Ramathuba, D.U. et al., 2020 [23] | Republic of South Africa | Ethical conflicts occurred when:

|

| Van Keer, R.L. et al., 2015 [25] | Belgium | Conflicts involved:

|

| Fernández-Castillo, R.J. et al., 2021 [26] | Spain | Nursing care has been influenced by fear and isolation, making it hard to maintain the humanization of the health care. |

| Jia, Y. et al., 2021 [27] | China | Major ethical challenges, conflicts, and dilemma appeared: neglected patient rights, the lack of emotional support, unequal exposure to the infectious environment, role ambiguity between doctors and nurses, insufficient response to urgency requirements of the situation, low sense of responsibility in nursing services, lack of knowledge and skills, inability in psychological adjustment and stress resistance |

| Gordon, J.M. et al., 2021 [28] | United States of America | Ethical conflicts occurred due to:

|

| Liu, X. et al., 2021 [29] | China | Three main categories of ethical dilemmas have been identified: ethical dilemmas in clinical nursing, ethical dilemmas in interpersonal relationships, and ethical dilemmas in nursing management. |

| Donkers, M.A. et al.,2021 [30] | Holland | Inadequate emotional support for patients and their families was the highest-ranked cause of moral distress for all groups of professionals. Moral distress scores during COVID-19 were significantly lower for ICU nurses and intensivists compared to one year prior |

| Falcó-Pegueroles, A. et al., 2021 [31] | Spain | Factors of ethical conflicts were identified:

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czyż-Szypenbejl, K.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W.; Falcó-Pegueroles, A.; Lange, S. Conflict Sources and Management in the ICU Setting before and during COVID-19: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031875

Czyż-Szypenbejl K, Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska W, Falcó-Pegueroles A, Lange S. Conflict Sources and Management in the ICU Setting before and during COVID-19: A Scoping Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031875

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzyż-Szypenbejl, Katarzyna, Wioletta Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, Anna Falcó-Pegueroles, and Sandra Lange. 2022. "Conflict Sources and Management in the ICU Setting before and during COVID-19: A Scoping Review of the Literature" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031875

APA StyleCzyż-Szypenbejl, K., Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W., Falcó-Pegueroles, A., & Lange, S. (2022). Conflict Sources and Management in the ICU Setting before and during COVID-19: A Scoping Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031875