Heart Failure Care: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Theory of Dyadic Illness Management

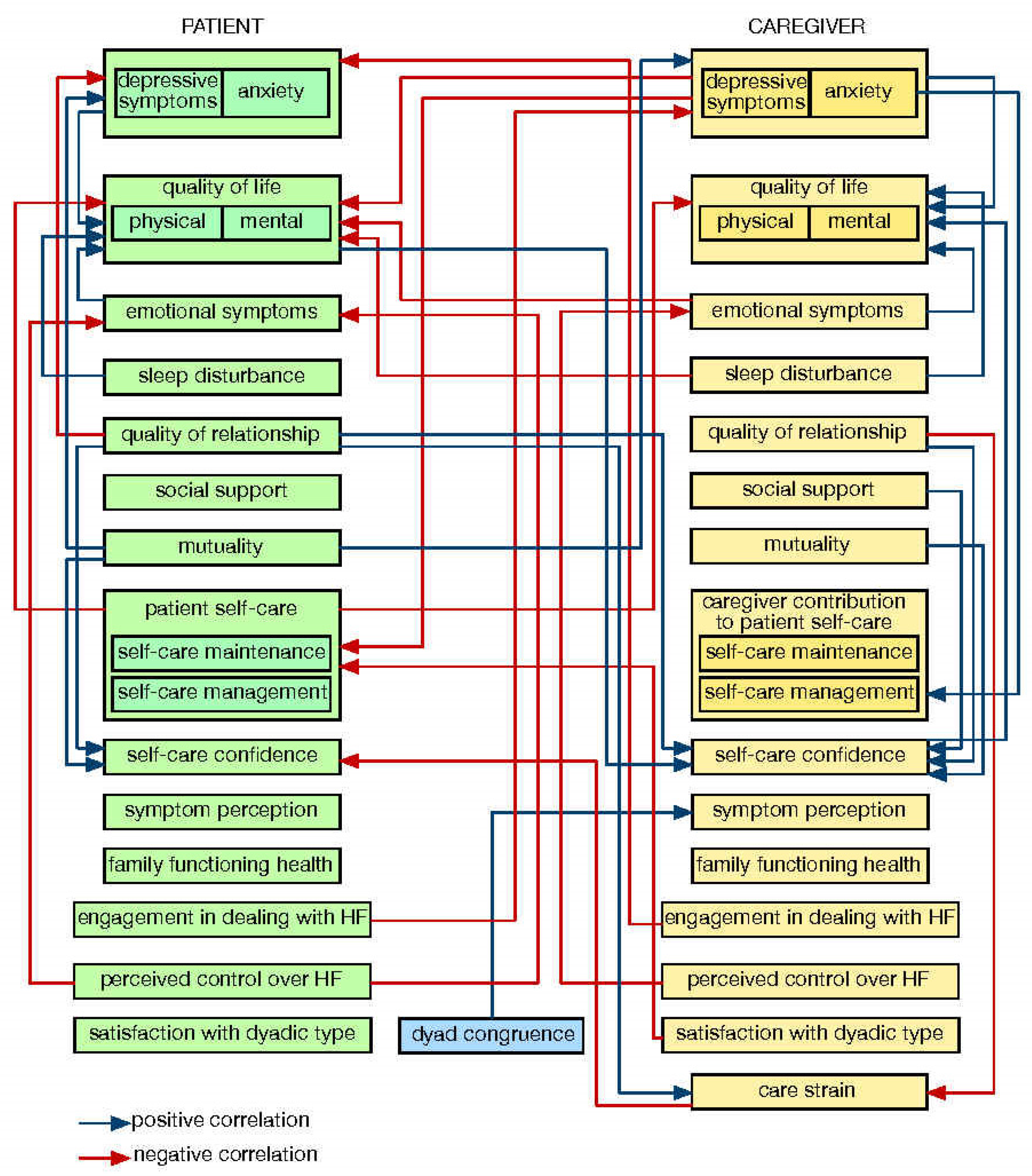

3.1. The Situation-Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self-Care

3.2. The Situation-Specific Theory of Caregiver Contribution to HF Self-Care

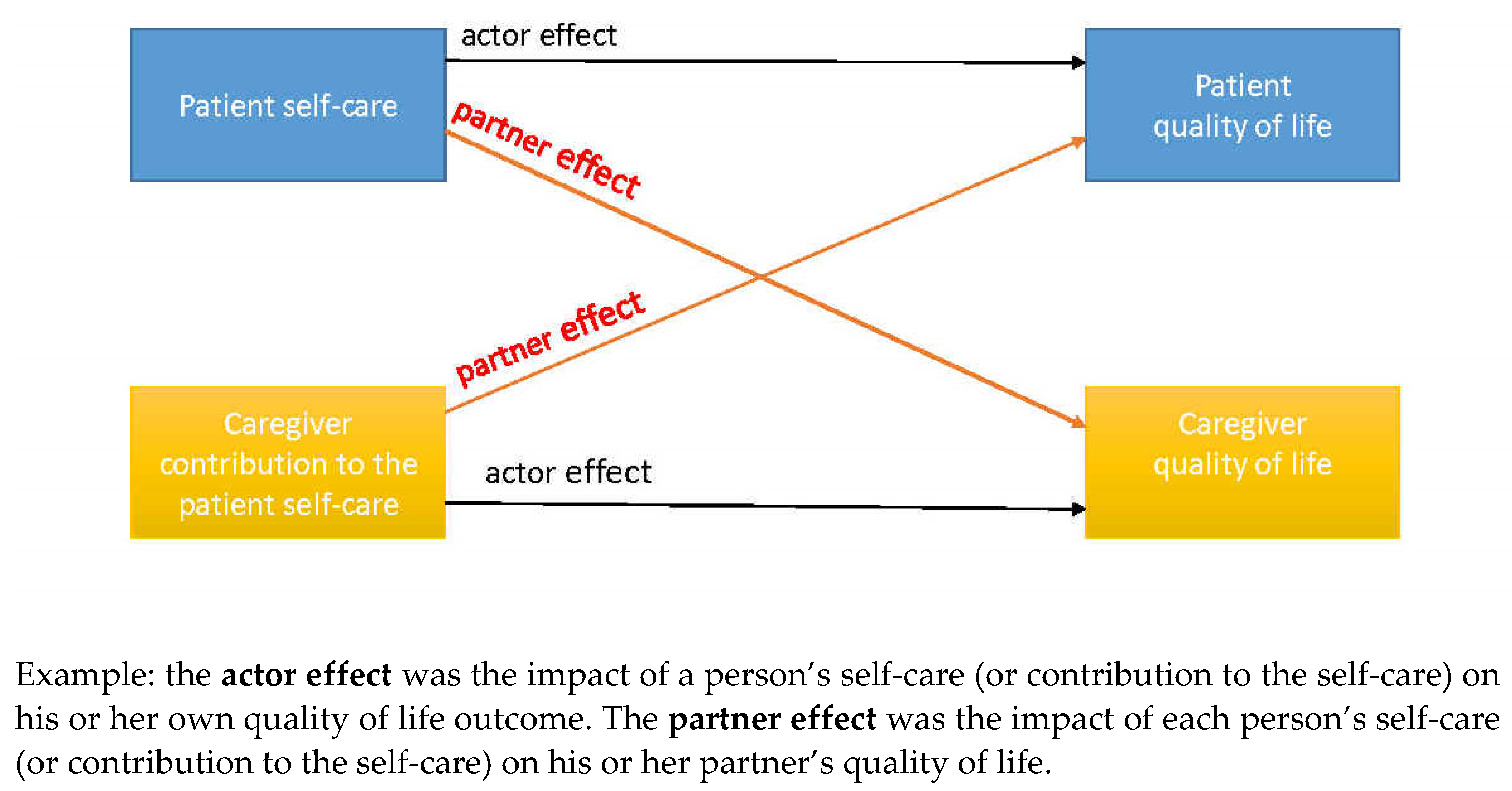

3.3. The Actor–Partner Interdependence Model

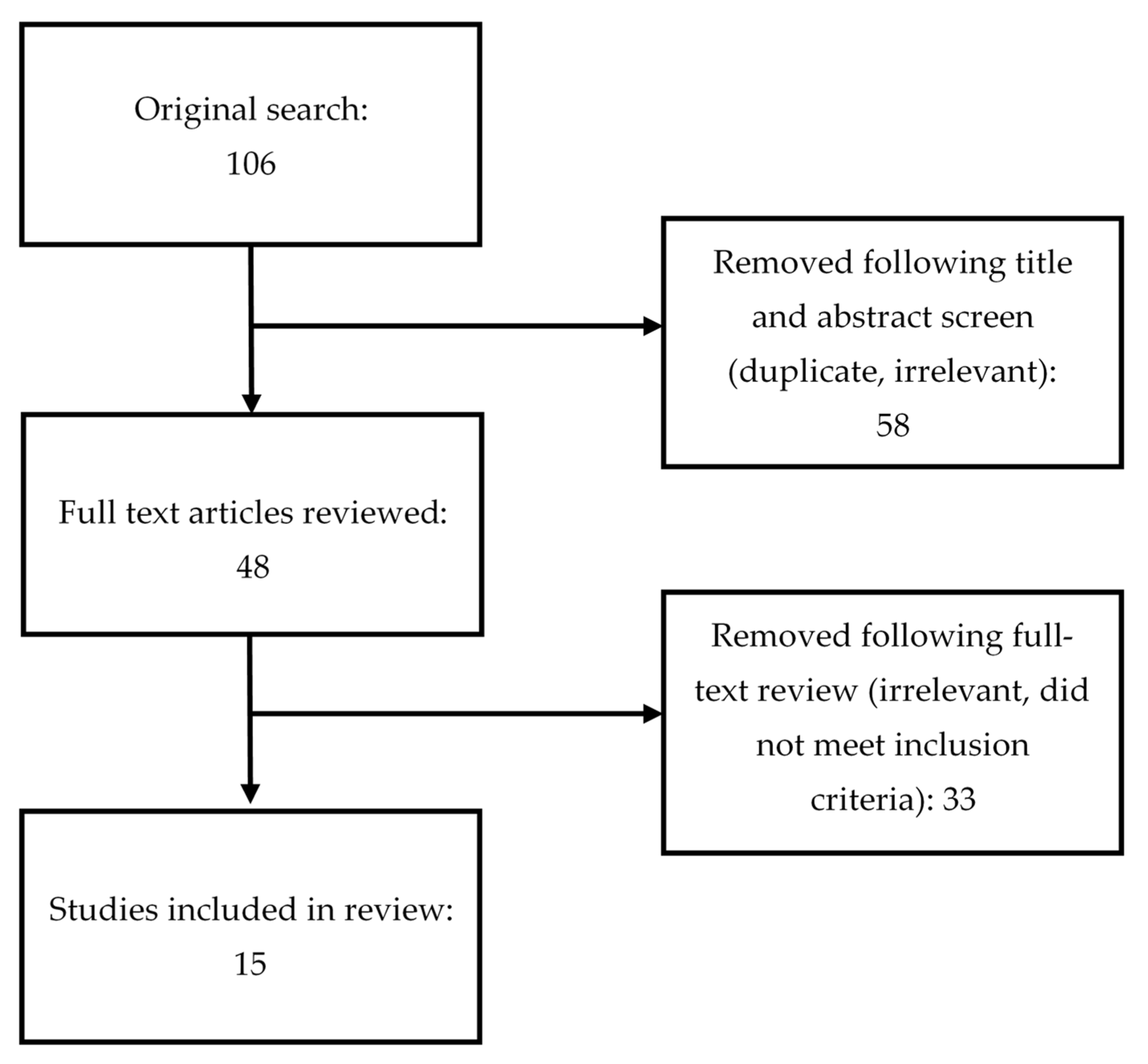

4. Data Search

5. Results

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.1.1. Quality of Life and Emotional Aspects of Dealing with HF

5.1.2. Dyadic HF Self-Care Confidence

5.1.3. Maintenance and Management

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Friedman, M.M.; Quinn, J.R. Heart Failure Patients’ Time, Symptoms, and Actions before a Hospital Admission. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008, 23, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauptman, P.J.; Masoudi, F.A.; Weintraub, W.S.; Pina, I.; Jones, P.G.; Spertus, J.A. Variability in the Clinical Status of Patients with Advanced Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2004, 10, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Moser, D.K.; Lennie, T.A.; Riegel, B. Event-Free Survival in Adults with Heart Failure Who Engage in Self-Care Management. Heart Lung J. Acute Crit. Care 2011, 40, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzapfel, N.; Löwe, B.; Wild, B.; Schellberg, D.; Zugck, C.; Remppis, A.; Katus, H.A.; Haass, M.; Rauch, B.; Jünger, J.; et al. Self-Care and Depression in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Heart Lung 2009, 38, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Moelter, S.T.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; Pressler, S.J.; De Geest, S.; Potashnik, S.; Fleck, D.; Sha, D.; Sayers, S.L.; Weintraub, W.S.; et al. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Is Associated with Poor Medication Adherence in Adults with Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2011, 17, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, V.V.; Buck, H.; Riegel, B. A Qualitative Meta-Analysis of Heart Failure Self-Care Practices among Individuals with Multiple Comorbid Conditions. J. Card. Fail. 2011, 17, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, C.Y. Somatic Awareness, Uncertainty, and Delay in Care-Seeking in Acute Heart Failure. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, J.T.; Vellone, E.; Lyons, K.S.; D’Agostino, F.; Riegel, B.; Paturzo, M.; Hiatt, S.O.; Alvaro, R.; Lee, C.S. Caregiver Determinants of Patient Clinical Event Risk in Heart Failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 16, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.G.; Harkness, K.; Wion, R.; Carroll, S.L.; Cosman, T.; Kaasalainen, S.; Kryworuchko, J.; McGillion, M.; O’Keefe-Mccarthy, S.; Sherifali, D.; et al. Caregivers’ Contributions to Heart Failure Self-Care: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 14, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas Dionne-Odom, J.; Hooker, S.A.; Bekelman, D.; Ejem, D.; McGhan, G.; Kitko, L.; Strömberg, A.; Wells, R.; Astin, M.; Metin, Z.G.; et al. Family Caregiving for Persons with Heart Failure at the Intersection of Heart Failure and Palliative Care: A State-of-the-Science Review. Heart Fail. Rev. 2017, 22, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.S.; Lee, C.S. The Theory of Dyadic Illness Management. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar, S.B.; Clark, P.C.; Quinn, C.; Gary, R.A.; Kaslow, N.J. Family Influences on Heart Failure Self-Care and Outcomes. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008, 23, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graven, L.J.; Grant, J.S. Social Support and Self-Care Behaviors in Individuals with Heart Failure: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidwell, J.T.; Higgins, M.K.; Reilly, C.M.; Clark, P.C.; Dunbar, S.B. Shared Heart Failure Knowledge and Self-Care Outcomes in Patient-Caregiver Dyads. Heart Lung J. Acute Crit. Care 2018, 47, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, H.G.; Hupcey, J.; Mogle, J.; Rayens, M.K. Caregivers’ Heart Failure Knowledge Is Necessary but Not Sufficient to Ensure Engagement With Patients in Self-Care Maintenance. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2017, 19, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.S.; Vellone, E.; Lee, C.S.; Cocchieri, A.; Bidwell, J.T.; D’Agostino, F.; Hiatt, S.O.; Alvaro, R.; Vela, R.J.; Riegel, B. A Dyadic Approach to Managing Heart Failure with Confidence. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, S64–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Dickson, V.V. A Situation-Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self-Care. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008, 23, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Dickson, V.V.; Faulkner, K.M. The Situation-Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self-Care Revised and Updated. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E.; Riegel, B.; Alvaro, R. A Situation-Specific Theory of Caregiver Contributions to Heart Failure Self-Care. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciere, Y.; Cartwright, M.; Newman, S.P. A Systematic Review of the Mediating Role of Knowledge, Self-Efficacy and Self-Care Behaviour in Telehealth Patients with Heart Failure. J. Telemed. Telecare 2012, 18, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.P.; Oliveira, C.; Pais-Vieira, M. Symptom Perception Management Education Improves Self-Care in Patients with Heart Failure. Work 2021, 69, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, M.; Clark, A.M. How Do Patients’ Values Influence Heart Failure Self-Care Decision-Making? A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 59, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaling, M.A.; Currie, K.; Strachan, P.H.; Harkness, K.; Clark, A.M. Improving Support for Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review to Understand Patients’ Perspectives on Self-Care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 2478–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.S.; Graven, L.J. Problems Experienced by Informal Caregivers of Individuals with Heart Failure: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 80, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.Y.; Oh, S.; Son, Y.J. Caring Experiences of Family Caregivers of Patients with Heart Failure: A Meta-Ethnographic Review of the Past 10 Years. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, C.A.; Upchurch, R. A Developmental-Contextual Model of Couples Coping with Chronic Illness across the Adult Life Span. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 920–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitko, L.; McIlvennan, C.K.; Bidwell, J.T.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Dunlay, S.M.; Lewis, L.M.; Meadows, G.; Sattler, E.L.P.; Schulz, R.; Strömberg, A. Family Caregiving for Individuals with Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e864–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, H.D.; Carey, E.P.; Fairclough, D.; Plomondon, M.E.; Hutt, E.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Bekelman, D.B. Burdensome Physical and Depressive Symptoms Predict Heart Failure–Specific Health Status Over One Year. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, A.; Luttika, M.L. Burden of Caring: Risks and Consequences Imposed on Caregivers of Those Living and Dying with Advanced Heart Failure. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 9, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, B.; Fleischmann, K.E.; Howie-Esquivel, J.; Stotts, N.A.; Dracup, K. Caregiving for Patients With Heart Failure: Impact on Patients’ Families. Am. J. Crit. Care 2011, 20, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, J.T.; Hostinar, C.E.; Higgins, M.K.; Abshire, M.A.; Cothran, F.; Butts, B.; Miller, A.H.; Corwin, E.; Dunbar, S.B. Caregiver Subjective and Physiological Markers of Stress and Patient Heart Failure Severity in Family Care Dyads. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 133, 105399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R.; Czaja, S.J.; Martire, L.M.; Monin, J.K. Family Caregiving for Older Adults. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 4, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonet Andreu, E.M.; Morales Asencio, J.M.; Canca Sanchez, J.C.; Sepulveda Sanchez, J.; Mesa Rico, R.; Rivas Ruiz, F. Effects and Consequences of Caring for Persons with Heart Failure: (ECCUPENIC Study) a Nested Case-Control Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressler, S.J.; Gradus-Pizlo, I.; Chubinski, S.D.; Smith, G.; Wheeler, S.; Sloan, R.; Jung, M. Family Caregivers of Patients with Heart Failure: A Longitudinal Study. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.G.; Hupcey, J.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Vellone, E.; Riegel, B. Heart Failure Care Dyadic Typology: Initial Conceptualization, Advances in Thinking, and Future Directions of a Clinically Relevant Classification System. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Strömberg, A. A Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2012, 35, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Van Lange, P.A.M. Interdependence, Interaction, and Relationships. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Kashy, D.A. Estimating Actor, Partner, and Interaction Effects for Dyadic Data Using PROC MIXED and HLM: A User-Friendly Guide. Pers. Relatsh. 2002, 9, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayens, M.K.; Svavarsdottir, E.K. Focus on Research Methods: A New Methodological Approach in Nursing Research: An Actor, Partner, and Interaction Effect Model for Family Outcomes. Res. Nurs. Health 2003, 26, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, T.; Macho, S.; Kenny, D.A. Assessing Mediation in Dyadic Data Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2011, 18, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.S.; Sadowski, T.; Lee, C.S. The Role of Concealment and Relationship Quality on Patient Hospitalizations, Care Strain and Depressive Symptoms in Heart Failure Dyads. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; Howie, K.; Leslie, S.J.; Angus, N.J.; Andreis, F.; Thomson, R.; Mohan, A.R.M.; Mondoa, C.; Chung, M.L. Evaluating Emotional Distress and Healthrelated Quality of Life in Patients with Heart Failure and Their Family Caregivers: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.L.; Moser, D.K.; Lennie, T.A.; Rayens, M.K. The Effects of Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety on Quality of Life in Patients with Heart Failure and Their Spouses: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 67, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawashdeh, S.Y.; Lennie, T.A.; Chung, M.L. The Association of Sleep Disturbances with Quality of Life in Heart Failure Patient-Caregiver Dyads. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 39, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, S.A.; Schmiege, S.J.; Trivedi, R.B.; Amoyal, N.R.; Bekelman, D.B. Mutuality and Heart Failure Self-Care in Patients and Their Informal Caregivers. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 17, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, J.T.; Vellone, E.; Lyons, K.S.; D’Agostino, F.; Riegel, B.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Hiatt, S.O.; Alvaro, R.; Lee, C.S. Determinants of Heart Failure Self-Care Maintenance and Management in Patients and Caregivers: A Dyadic Analysis. Res. Nurs. Health 2015, 38, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.G.; Mogle, J.; Riegel, B.; McMillan, S.; Bakitas, M. Exploring the Relationship of Patient and Informal Caregiver Characteristics with Heart Failure Self-Care Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: Implications for Outpatient Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E.; Chung, M.L.; Cocchieri, A.; Rocco, G.; Alvaro, R.; Riegel, B. Effects of Self-Care on Quality of Life in Adults with Heart Failure and Their Spousal Caregivers: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J. Fam. Nurs. 2014, 20, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamali, M.; Konradsen, H.; Stas, L.; Østergaard, B. Dyadic Effects of Perceived Social Support on Family Health and Family Functioning in Patients with Heart Failure and Their Nearest Relatives: Using the Actor–Partner Interdependence Mediation Model. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, A.; Liljeroos, M.; Ågren, S.; Årestedt, K.; Chung, M.L. Associations Among Perceived Control, Depressive Symptoms, and Well-Being in Patients With Heart Failure and Their Spouses: A Dyadic Approach. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021, 36, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.S.; Hiatt, S.O.; Gelow, J.M.; Auld, J.; Mudd, J.O.; Chien, C.V.; Lee, C.S. Depressive Symptoms in Couples Living with Heart Failure: The Role of Congruent Engagement in Heart Failure Management. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1585–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E.; Chung, M.L.; Alvaro, R.; Paturzo, M.; Dellafiore, F. The Influence of Mutuality on Self-Care in Heart Failure Patients and Caregivers: A Dyadic Analysis. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellafiore, F.; Chung, M.L.; Alvaro, R.; Durante, A.; Colaceci, S.; Vellone, E.; Pucciarelli, G. The Association between Mutuality, Anxiety, and Depression in Heart Failure Patient-Caregiver Dyads. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugajski, A.; Buck, H.; Zeffiro, V.; Morgan, H.; Szalacha, L.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. The Influence of Dyadic Congruence and Satisfaction with Dyadic Type on Patient Self-Care in Heart Failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitko, L.A.; Hupcey, J.E.; Pinto, C.; Palese, M. Patient and Caregiver Incongruence in Advanced Heart Failure. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2015, 24, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, J.T.; Lyons, K.S.; Lee, C.S. Caregiver Well-Being and Patient Outcomes in Heart Failure a Meta-Analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 32, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.; Thompson, D.R.; Szer, D.; Greig, J.; Ski, C.F. Dyadic Incongruence in Chronic Heart Failure: Implications for Patient and Carer Psychological Health and Self-Care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4804–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retrum, J.H.; Nowels, C.T.; Bekelman, D.B. Patient and Caregiver Congruence: The Importance of Dyads in Heart Failure Care. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Mudd, J.O.; Auld, J.; Gelow, J.M.; Hiatt, S.O.; Chien, C.V.; Bidwell, J.T.; Lyons, K.S. Patterns, Relevance and Predictors of Heart Failure Dyadic Symptom Appraisal. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 16, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.C.; Kyle, D.J. The Role of Perceived Control in Coping with the Losses Associated with Chronic Illness. In Loss and Trauma: General and Close Relationship Perspectives; Harvey, J.H., Miller, J.H., Eds.; Brunner-Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2000; pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Olchowska-Kotala, A. Illness Representations in Individuals with Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Willingness to Undergo Acupuncture Treatment. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2013, 5, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Norman, P. Information Processing in Illness Representation: Implications from an Associative-Learning Framework. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, S.A.; Grigsby, M.E.; Riegel, B.; Bekelman, D.B. The Impact of Relationship Quality on Health-Related Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients and Informal Family Caregivers: An Integrative Review. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, S52–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.L.; Lennie, T.A.; Mudd-Martin, G.; Dunbar, S.B.; Pressler, S.J.; Moser, D.K. Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Heart Failure Negatively Affect Family Caregiver Outcomes and Quality of Life. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 15, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonet-Andreu, E.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Alcalá Gutierrez, P.; Cruzado Alvarez, C.; López-Moyano, G.; Mora Banderas, A.; López-Leiva, I.; Canca-Sanchez, J.C. Health-Related Quality of Life and Use of Hospital Services by Patients with Heart Failure and Their Family Caregivers: A Multicenter Case-Control Study. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020, 52, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge-Samitier, P.; Durante, A.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Fernández-Rodrigo, M.T.; Juárez-Vela, R. Sleep Quality in Patients with Heart Failure in the Spanish Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Schlesinger, S.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Tonstad, S.; Norat, T.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J. Physical Activity and the Risk of Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, M.; Börjesson, M. The Importance of Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness for Patients with Heart Failure. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 176, 108833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchera, B.; Delloiacono, D.; Lawless, C.A. Best Practices for Patient Self-Management: Implications for Nurse Educators, Patient Educators, and Program Developers. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2018, 49, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntsinger, M.E.; Rabara, R.; Peralta, I.; Doshi, R.N. Current Technology to Maximize Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Benefit for Patients With Symptomatic Heart Failure. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2015, 26, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/Year | Country; Sample | Main Outcome Measure(s) | Aim of the Study | Main Results | Main Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Lyons et al., 2020) [41] | USA; 60 dyads (patient–spousal caregiver); 67% male patients; Mage = 59.5 (patient) and Mage = 57.8 (caregiver) | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9); Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI); Emotional-Intimacy-Disruptive-Behavior Scale; Mutuality Scale | To examine the role of interpersonal factors (i.e., concealment and relationship quality) on the depressive symptoms of HF patients and their spouse care partners, care partner strain, and patient hospitalizations |

- Patients who conceal their worries and concerns from their care partner may be at risk for increased depressive symptoms and hospitalizations - When patients perceived greater relationship quality with spouse care partners, they reported significantly less depressive symptoms; when spouse care partners perceived greater relationship quality with patients, they reported significantly less care strain - When patients perceived greater relationship quality, spouse care partners reported significantly higher care strain | Patient concealment of worries or concerns (lack of open communication) is a risk factor for patient depressive symptoms and healthcare utilization; one’s own perception of the relationship could have the protective factor. |

| (Thomson et al., 2020) [42] | UK; 41 dyads (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregivers); 78% male patients; Mage = 68.6 (patient) and Mage = 65.8 (caregiver) | Brief Symptom Inventory; Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire | To examine relationship between emotional symptoms and health-related quality of life |

- No differences in emotional symptoms and health-related quality of life between patients with heart failure and their caregivers - Patients’ and caregivers’ emotional symptoms were associated with their own health-related quality of life (actor effect) - Caregivers’ emotional symptoms negatively influenced their partners’ health-related quality of life (partner effect) | Emotional aspects of dealing with heart failure may affect the caregivers as much as their partners who have the illness; the substantial impact of caregivers’ emotional symptoms on the health-related QoL of patients suggest that the caregiver’s emotional well-being needs to be addressed. |

| (Chung et al., 2009) [43] | USA; 58 dyads (patient–spousal caregiver); 71% male patients; Mage = 61.7 (patient) and Mage = 57.5 (caregiver) | Brief Symptom Inventory; Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire | To explore impact of emotional distress on quality of life (QoL) |

- Both patients’ and spousal caregivers’ depressive symptoms and anxiety influenced their own quality of life (actor effect) - Spousal caregivers’ depressive symptoms and anxiety negatively impacted patients’ quality of life, with high depressive symptoms or anxiety in the caregiver spouse predicting poorer quality of life in the patient (partner effect) | Patients with HF may be particularly vulnerable to the emotional distress of their spouse caregivers; interventions to reduce depression and anxiety and to improve patients’ quality of life should include both patients and spouses. |

| (Al-Rawashdeh et al., 2017) [44] | USA; 78 dyads (patient–spousal caregiver); 56% male patients; Mage = 62.2 (patient) and Mage = 59.5 (caregiver) | Sleep disturbance: a composite score of four common sleep complaints; Short-Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12) | To determine whether sleep disturbances of patients and their spousal caregivers predicted their own and their partners’ quality of life | - Each individual’s sleep disturbance predicted their own poor physical and mental well-being (actor effect), while spousal caregivers’ sleep disturbance predicted patient’s mental well-being (partner effect) | Patients’ mental well-being is sensitive to their spouses’ sleep disturbance; interventions targeting improving sleep and quality of life may have to include both patients and spousal caregivers. |

| (Lyons et al., 2015) [16] | Italy; 329 dyads (patient–spousal caregiver or adult children); 56% male patients; Mage = 76.8 (patient) and Mage = 58.3 (caregiver) | Self-Care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI); Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; Short-Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12) (single items); Caregiver Burden Inventory; COPE | To identify individual and dyadic determinants of self-care confidence |

- Both patients and caregivers reported moderate levels of confidence, with caregivers reporting slightly higher confidence than patients - Significant heterogeneity in confidence across the dyads - Patient and caregiver levels of confidence were significantly associated with greater patient-reported relationship quality and better caregiver mental health (actor and partner effects) - Patient confidence in self-care was associated with patient female gender, non-spousal care dyads, poor caregiver physical health, and low care strain (partner effect) - Caregiver confidence to contribute to self-care was significantly associated with poor emotional quality of life in patients (partner effect) and greater perceived social support by caregivers (actor effect) | Caregiver mental health must be prioritized; better caregiver mental health and greater relationship quality were the modifiable hallmarks of better self-care confidence in both the patient and the caregiver; the level of confidence in dyads is generallylower-than-adequate. |

| (Hooker et al., 2018) [45] | USA; 99 dyads (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregiver); 34% male patients; Mage = 65.6 (patient) and Mage = 57.4 (caregiver) | Mutuality Scale of the Family Caregiving Inventory; Self-care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI); The Zarit Burden Inventory-Short Form (ZBI-SF) | To examine the associations among patient/caregiver self-care confidence and mutuality and caregiver perceived burden. |

- Patients and caregivers who perceived better mutuality were more confident in patient self-care (actor effect only) - Caregivers with greater mutuality reported less perceived burden | Mutuality in patient–caregiver dyads is associated with patient self-care and caregiver burden and may be an important intervention target to improve self-care and reduce hospitalizations; there is a need for screening for the quality of the patient–caregiver relationship. |

| (Bidwell et al., 2015) [46] | Italy; 364 dyads (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregiver); 57% male patients; Mage = 76.2 (patient) and Mage = 57.4 (caregiver) | Short-Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12); Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; The Barthel Index; Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI); Carers of Older People in Europe Index (COPE); Self-care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI); perceived quality of the relationship between patient and caregiver | To identify determinants of patient and caregiver contributions to HF self-care maintenance (daily adherence and symptom monitoring) and management (appropriate recognition and response to symptoms) |

- Both patients and caregivers reported low levels of HF maintenance and management behaviors - Non-spousal relationship type was a significant determinant of higher caregiver contributions to patient self-care management - Better relationship quality was associated with better patient self-care and caregiver contributions to patient self-care although it was the individual’s own perception of the quality of the relationship that was important - Even mild cognitive impairment can have a substantial impact on patient’s self-care | There is the need to examine HF self-care maintenance and management in the context of the patient-caregiver dyad; significant individual and dyadic determinants of self-care maintenance and self-care management included gender, quality of life, comorbid burden, impaired ADLs, cognition, and hospitalizations. |

| (Buck et al., 2015) [47] | USA; 40 dyads (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregiver); 70% male patients; Mage = 71.2 (patient) and Mage = 58.8 (caregiver) | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); Brief Symptom Inventory; Dyadic Adjustment Scale; Self-care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI) | To describe the dyadic characteristics of mood and perception of the relationship in HF patients and caregivers |

- Higher levels of depression or anxiety for the caregiver predicted lower HF self-care maintenance scores for the patient (partner effect) - Higher caregiver anxiety predicted lower caregiver HF self-care management scores, and higher caregiver ratings of relationship quality predicted greater caregiver ratings of self-efficacy (actor effects) | Caregivers’ mood states and perception of the relationship impacts the patient and their own engagement in HF self-care as well as the caregiver’s self-efficacy. |

| (Vellone et al., 2014) [48] | Italy; 138 dyads (patient–spousal caregiver); 64% male patients; Mage = 73.6 (patient) and Mage = 70.4 (caregiver) | Self-care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI); Short Form 12 (SF-12) | To explore relationship between self-care behavior and quality of life |

- Higher self-care was related to lower physical QoL in patients and caregivers - Higher self-care maintenance in patients was associated with better mental QoL in caregivers - In caregivers, confidence in the ability to support patients in self-care was associated with improved caregivers’ mental QoL | In caregivers, confidence in the ability to support patients in the performance of self-care improved caregivers’ mental QoL; interventions that build the caregivers’ confidence are needed. |

| (Shamali et al., 2019) [49] | Denmark; 312 dyads (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregiver); 71% male patients; Mage = 64.7 (patient) and Mage = 58.9 (caregiver) | The Family Functioning, Health and Social Support(FAFHES) | To examine whether perceived social support from nurses is associated with better family functioning of patients with heart failure and their nearest relatives |

- The higher the level of family health of the nearest relative, the better the family functioning of the patient (partner effect) - High level of perceived social support from nurses was associated with a higher level of family health and better family functioning in patients with HF and their partner - family health partially (in the patient) and completely (in the nearest relative) mediated the association between social support and family functioning | Social support from nurses could increase the level of family health and family functioning. |

| (Strömberg et al., 2021) [50] | Sweden; 155 dyads (patient–spousal caregiver); 75% male patients; Mage = 71 (patient) and Mage = 69 (caregiver) | Control Attitude Scale; Beck Depression Inventory; Short-Form 36 | To examine on whether the patients’ perceived control over the management of HF and depressive symptoms predicts their own and their spouses’ physical and emotional well-being and depressive symptoms |

- Perceived control over HF was significantly associated with their partners’ emotional well-being - Perceived control over HF had actor effect on emotional well-being for patients | Lack of control over heart disease in any member of the dyads makes their partner feel more insecure and worried; perceived control should be routinely assessed in both patients and spouses during HF follow-up. |

| (Lyons et al., 2018) [51] | USA; 60 dyads (patient–spousal caregiver); 67% male patients; Mage = 59.4 (patient) and Mage = 57.7 (caregiver) | European Heart Failure Self-Care Behavior Scale (EHFScB-9); Self-care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI); Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) | To examine the role of congruent engagement in HF-management behaviors on the depressive symptoms of the couple living with HF |

- Higher levels of engagement by one’s partner were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms for both membersof the couple - When couples engage in similar levels of HF-management behaviors, spouses experience lower depressive symptoms | Partner’s level of engagement plays an important role in managing the illness |

| (Vellone et al., 2018) [52] | Italy; 366 dyads (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregiver); 56% male patients; Mage = 71.9 (patient) and Mage = 58.6 (caregiver) | Mutuality Scale; Self-care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI) | To evaluate the influence of the total mutuality and its dimensions on self-care maintenance, management, and confidence in HF patient–caregiver dyads |

- Higher patient mutuality was associated with better self-care maintenance and confidence, and higher caregiver mutuality was associated with better caregiver self-care confidence - Patients and caregivers respond better to symptoms when they experience feelings of appreciation, help, comfort, confidence, and emotional support -If one member of the dyad feels higher mutuality toward the other member of the dyad, this improves only his or her own self-care confidence and not the self-care confidence of the other member of the dyad | The quality of the relationship within the dyad is a protective factor in illness management as mutuality improves self-care in the dyad; self-care maintenance in both patients and caregivers could be improve by shared pleasurable activities within the dyad. |

| (Dellafiore et al., 2019) [53] | Italy; 366 dyads (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregiver); 56% male patients; Mage = 71.9 (patient) and Mage = 53.8 (caregiver) | Mutuality Scale; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | To evaluate the associations among mutuality, anxiety, and depressionin HF patient–caregiver dyads |

- Higher patient mutuality in his/her relationship with the caregiver was associated with lower patient anxiety and depression - Higher patient mutuality was associated with higher caregiver depression | Good relationship with patients is not “protective” against anxiety and depression in caregivers. |

| (Bugajski et al., 2020) [54] | Italy; 277 dyad; (patient–spousal and non-spousal caregiver); 55% male patients; Mage = 75.5 (patient) and Mage = 52.8 (caregiver) | Self-care of HF Index (SCHFI) and Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF Index (CC-SCHFI); The Dyadic Symptom Management Type (DSMT) | To examine the role of HF self-care dyadic type congruence on patient self-care (maintenance, symptom perception, and management) |

- Dyad congruence was a significant predictor of patient’s symptom perception scores but not self-care maintenance or management. - Caregiver’s satisfaction with the dyad was differentially and significantly associated with self-care (inversely with patient self-care maintenance and positively with patient self-care management) | Congruence in HF dyads is associated with better patient symptom perception; the important factor of dyadic HF self-care is the relationship between partners. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uchmanowicz, I.; Faulkner, K.M.; Vellone, E.; Siennicka, A.; Szczepanowski, R.; Olchowska-Kotala, A. Heart Failure Care: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041919

Uchmanowicz I, Faulkner KM, Vellone E, Siennicka A, Szczepanowski R, Olchowska-Kotala A. Heart Failure Care: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041919

Chicago/Turabian StyleUchmanowicz, Izabella, Kenneth M. Faulkner, Ercole Vellone, Agnieszka Siennicka, Remigiusz Szczepanowski, and Agnieszka Olchowska-Kotala. 2022. "Heart Failure Care: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)—A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041919

APA StyleUchmanowicz, I., Faulkner, K. M., Vellone, E., Siennicka, A., Szczepanowski, R., & Olchowska-Kotala, A. (2022). Heart Failure Care: Testing Dyadic Dynamics Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041919