This exploratory study aimed to investigate the prevalence and effect of injury in British horseracing staff. The results established high self-reported incidents of pain, musculoskeletal injuries, and suspected concussion, with several risk factors for injury type related to occupational demands, such as working hours. When injured, staff typically relied on pain management strategies to continue working, and if adaptations were required at work, these typically involved reduced duties, or restrictions in ridden activities. Horseracing staff were less likely to report or take time-off for invisible injuries, such as concussion or musculoskeletal pain, compared to fractures, and attitudes towards injury reporting and management were influenced by several factors, including financial circumstances, perception of staff shortages, previous injury experiences, and perception of employer and peer expectations.

4.1. Injury and Risk Factors

Injury rates were high in racing staff; only 11.9% of participants reported no injuries in the last 12 months. Injury incidence was estimated at 0.166 injuries/person for the population of British horseracing staff (~7000), with staff in this survey reporting 3.30 injuries/person in the 12-month period surveyed. Racing staff have previously reported very high injury incident rates, with over 50% of yards reporting accidents [

2,

4,

8]. Racing staff typically work long, unsocial hours, with 52.53% (

n = 103) of staff typically working more than 8 h per day. In a recent study, trainers reported long work hours as one of the sources of stress in their profession [

9], whilst over 85% of stable staff surveyed in Australia reported working more than 40 h/week, averaging 46 h/week in full-time staff [

7]. Mandatory overtime can reduce perceptions of job control, which is a predictor for burnout, and can result in an increased number of sick days for the same injury compared to those staff who did not work overtime [

13]. This may be a concern for racing staff who previously reported working overtime or on days off to cover reduced numbers of staff on the yard on race days [

17]. The National Association of Racing Staff (NARS) report that no employee should work more than 48 h on average over a 7-day period in Great Britain [

48], however, limited research is available to confirm this. Increased hours have been reported to link to higher levels of fatigue and psychological distress, which can increase the risk factor for injury in several occupations, including veterinary, nursing and construction industries [

49,

50,

51]. Care should be taken when considering working hours in relation to job demand in this study, as data collection took place during the 3rd national coronavirus lockdown between January and February 2021 [

52]. Whilst many industries were closed during this period due to government-imposed restrictions, previous research from the 1st national lockdown in March 2020 shows that most horseracing staff were likely to be working the same number of hours, with only 32.8% working fewer hours during a COVID-19 lockdown than normal [

34]. This suggests that the working behaviours reported in this study are representative of typical occupational demands for horseracing staff.

Very few studies have formally investigated injury incidence or the patterns of injury in stable staff [

4,

7,

8], but the research available suggests the profile of injury for staff is different to that seen in jockeys, who have received greater representation within the empirical literature [

5,

7,

53,

54,

55]. The most common injuries reported in this study were bruises and lacerations, upper and lower back pain, chronic musculoskeletal issues, and suspected concussion, which aligns with Cowley et al. [

5], who found higher rates of back injuries in staff compared to jockeys (16% vs. 9%, respectively). Chronic and overuse injury have also been reported for equestrian athletes in other disciplines, with between 74–96% of riders reporting pain, predominately linked to the neck and back [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Occupational demands between Olympic-discipline riders and those working in horseracing could be seen to be similar; long hours and weekend/shift work, workforce instability, and low job control due to strict health and safety requirements of the role, and the requirement to maintain equine welfare standards—all of which increase the risk of injury [

2,

14,

60,

61]. Daily repetitive tasks for horseracing grooms, such as sweeping, mucking out or lifting and carrying, are all risk factors for increased neck and back pain [

62,

63,

64,

65]. Overuse injuries in horseracing staff could decrease the efficiency of the workforce [

13,

14,

15], and issues of poor horse welfare can also arise when staff are not fully engaged in their daily tasks, a potential consequence of physical and mental fatigue [

19].

Several factors influenced the type of injuries that staff were likely to have experienced in a 12-month window, including perceived job control, and working hours. Organisational structure and working conditions have previously been reported as causal factors for injury risk in occupational settings [

15]. Staff who felt they had little control over their daily tasks at work were more likely to have experienced musculoskeletal injuries in the last 12 months, whilst those staff who had full control over their job were more likely to report no injuries sustained. Job control is defined as the feeling of autonomy in the workplace, through control over work shift patterns, hours, and responsibility for management and timing of daily tasks and is often limited in high-risk roles due to health and safety [

61]. Racing grooms are required to work long hours, with increasing weekend shift work due to the expansion of the fixture list [

17]. Anecdotal reports identify struggling to access doctor’s appointments or co-ordinate calendars for off-work activities due to ever changing schedules [

2,

7,

9], which has been exacerbated in recent months by the impact of COVID-19 on racing staff (see [

34] for further detail). In addition, staff are required to demonstrate stringent management practices to ensure high standards of horse care and consequently welfare, such as in handling and exercising to avoid equine injury. The rigor of these management practices can result in a perceived loss of job control, which was recently reported by stable staff in an industry study [

10]. Research suggests that roles with limited control over daily tasks, and that have increased physiological and psychological demands such as seen for racing staff, can be classified as high strain roles [

13]. These highly demanding roles increase physiological arousal that cannot be effectively managed due to limited job control, therefore resulting in internal mental fatigue and physical exhaustion [

36,

61]. Employees in high-strain occupations may also lack the ability to recover if annual leave or days off are limited, or if off-work situations are directly linked to the job role, i.e., provision of employee housing, as observed in the racing industry [

2,

61]. The inability to recover can lead to accumulation fatigue, reduced coping mechanisms and subsequent injury from poor decisions [

60] which may explain the high injury incidence and the associations seen here between perceived job control and injury type. Previous research has identified that where occupational demands are unable to be alleviated due to health and safety regulations, such as in training yards and studs, individual intervention strategies are an effective method to reduce injury occurrence [

64,

66]. This may include staff education about early identification of increased muscle tension as a predictor of injury, or management of equipment use in repetitive tasks, such as mucking out, which can reduce the incidence of back pain [

64].

In addition, the current study identified that staff working 10–11 h were at increased risk of lower back pain compared to other staff, whilst those working 8–9 h were more likely to experience more musculoskeletal injuries, such as sprains, strains, and muscle pain. Working longer hours has been seen in other industries to increase the risk of injury [

14] due to greater levels of physiological and psychological fatigue, combined with a lack of recovery time. Whilst the National Association of Racing Staff (NARS) recommends a 48-h average working week (over a 7-day period), de Castro and Fujishiro [

13] identified that working over 40 h per week increases the risk of work-based illnesses, sick days, and back pain. Over half of the participants in this study (52.53%,

n = 103) were working more than an average 40-h week (typically 8+ h per day), with 6.1% working an average 60-h week, which may explain the increased injury reported in staff working longer hours. Due to the nature of the role in caring for animals as well as the financial challenges trainers face related to recruitment and retention in the current climate [

9,

17,

67,

68], recommendations to reduce working hours for stable staff as a method to reduce injury risk are unrealistic. Therefore, other preventative strategies are required to maximise health and safety for racing staff in training and stud yards to counteract the effect of physical fatigue from working longer hours. Whilst longer hours are typically associated with increased stress responses, and higher risk of injury [

13,

14]; perception of working hours by staff in other vocational sectors, such as nursing and health, or veterinary, has also been shown to influence injury risk [

69]. Satisfaction with working hours reduces employee perception of associated stress [

69,

70], which could reduce the risk of occupational injury, as daily stressors have been found to increase injury risk through altered cognitive function, memory loss, sleep disruptions and impaired relationships [

15,

71,

72]. Racing staff in this survey who wished to work less hours were more likely to report injuries in the last 12 months, which would suggest that work-place satisfaction is a key contributor to injury risk in this population and should be explored further.

Something of note within these data is the unexpectedly high rate of survey drop out (43.75%) after participants reported their personal injury experiences. This finding would suggest that participants who began the survey were willing to report their injuries but chose not to continue the survey when asked to consider the psychosocial factors or wider effects of the injury experienced. It has been suggested that pain is a culturally accepted construct within certain vocations, and thus positively embraced as a sign of success or ‘fitting in’ with the culture [

73,

74], which could be an explanation for the survey engagement behaviours seen here. Anecdotally, those working in equestrian and horseracing industries may be more likely to verbalize injury as a ‘badge of honour’, something recently identified in McVey [

75], who found riders in their ethnographic study were likely to show off injuries as a sign of their commitment to the hard work of owning and riding horses. Dancers have previously reported comparing their injuries to one another with a sense of pride [

73], and view pain as a sign of personal improvement [

76], whilst female rugby players describe bruises as a sign of physical ability and strength [

77]. In addition, farmers identified an honour and prestige attached to continuing to work despite injury [

78]. Wider equestrian culture has been shown to take a stoic approach to injury, and riders often revel in physical risk rather than take steps to mitigate them, which may be similar to the attitude seen in horseracing staff here [

75]. The drive to keep working through injury or pain could be seen as an embodied necessity, and stopping work undermines the social and cultural capital derived from the activity or engagement in that community [

75,

79,

80]. The potential disengagement from injury discussion beyond the identification of injuries as a ‘list of accomplishments’ seen in this population warrants further consideration and is something researchers should factor into study design moving forwards when working with horseracing staff.

4.2. Injury Management

During the 12-month period, staff typically relied on pain management strategies to continue working whilst injured. Over half of staff reported to using over-the-counter medication at least once per week to manage daily tasks at work, with 18% taking painkillers daily. Only 10% of staff did not use any medication to manage physical pain at work. Use of prescription medication for pain relief has previously been reported in 4–8% of racing staff [

10], although this was not categorized by drug type, or reason for use. The use of analgesics as a tool to comply with presenteeism is seen in several vocations, including sporting athletes [

81]. There is a high reported use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) in sport [

82,

83] with Harle

et al., [

84] suggesting over 50% of elite athletes use oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at international events. Similarly, equestrian athletes report a high prevalence of taking medication, with 51% of dressage riders [

58], 67% of show jumpers [

57], and 96% of event riders [

56] using pain relief medication during equestrian activities (training and competing). Overbye [

81] suggests that the practice of using analgesics to maintain performance, improve recovery and reduce the impact of injury has become a socially accepted practice in sport, and is often encouraged by peers and coaches as “routine” despite potential negative side effects. When taken frequently, NSAID’s can cause side effects to the gastrointestinal system and kidneys [

81,

85], with some research suggesting long term analgesic use can result in negative effects on muscle recovery [

86], which would further increase the risk of injury and may partially explain the higher rates of chronic pain observed in older racing staff [

2]. The high reported use of painkillers within this study to maintain daily occupational demands highlights a potential problem with the overuse of pain medication in the racing industry and is something that requires further investigation into the long-term consequences on staff health.

Over half the racing staff surveyed here reported continuing to work without any adaptations or accommodations, whilst less than a quarter of staff took time off in relation to the injury sustained, similar to previous industry reports [

4,

8,

10]. Of those who continued to work, adaptations to working environment mostly involved reduced duties or restrictions in ridden activity. Most workers with recurrent musculoskeletal pain or discomfort continue to work, reporting minimal time loss [

87], however, this has previously been seen to decrease workplace productivity [

88]. Due to concerns with staffing structure, and the decreased workforce retention seen in horseracing presently, staff who are ‘not pulling their weight’ may be seen to be an inconvenience or nuisance, which could result in loss of job security, which is already of concern to this population [

10,

17,

34]. The inability to work at normal capacity, due to injury or fatigue, may also increase the risk of injury to horses under the care of stable staff or lead to poor management practices [

18,

19]. Lack of concentration, physical fatigue and burnout resulting from a stressful working environment or reduced mental resilience can negatively impact task efficiency by affecting visual acuity, accuracy, and individual reaction time [

60]. Slower reactions, or loss of focus around horses could result in preventable injury to both parties or result in subpar management and care of the horse, thus highlighting the importance of a healthy workforce to maintain high equine welfare standards within the sector.

Despite concerns about presenteeism in horseracing staff, Crawford et al. [

89] identify that staff are not required to be 100% fit to return to work, however, accommodations should be made, based on work ability, to facilitate a safe return, which was seen in a large group of participants in this study. Research suggests that workplace interventions can make return to work easier, enhance quality of life and reduce the cost of injuries to the healthcare industry [

90]. Returning to work earlier can also result in improvements in physical recovery and has psychosocial benefits, such as enhanced social connection and heightened morale [

91]. Return to work is often facilitated by temporary modifications to the job role [

87], managed by the employer [

22,

23] and may be physical, social/organisational, or psychological [

89]. This study saw a range of physical adaptations, such as changes in job requirements or restricted duties, as well as flexibility in changing work hours which are classified as organisational adaptations. Williams et al. [

90] suggests that adaptations of both task requirements (physical) e.g., non-ridden duties or less boxes to muck out, and working hours (organisational) are effective at managing return to work from injury, whilst modification to the working environment overall has been shown to be effective at reducing the perception of pain. Modification of tasks is a common workplace adaptation following injury or illness [

21,

24] and has been linked to increased perception of job control, a factor that could mitigate the risk of re-injury and improve overall job satisfaction [

23,

24,

36,

61]. Whilst adaptations were reported in this study, the ability to temporarily modify job roles within horseracing would be dependent on managerial culture and staffing structure within the yard environment. Many training and stud yards are understaffed [

17,

67,

68], increasing the difficulty to provide adequate workplace adaptations for injured staff. Trainers previously reported finding staff cover a substantial workplace stressor [

9], whilst staff reported an increase in physical effort because of a diminished workforce [

17,

34]. Staff in this study felt guilty that colleagues were “carrying the weight” whilst they were injured, which may suggest this population would be unlikely to follow strict restrictions on workplace tasks if they were to be implemented. The staff shortage was further exacerbated by ongoing COVID-19 restrictions in place [

23], whereby staff were under increased pressure to maintain high standards whilst adhering to social distancing requirements, hygiene protocols and covering staff who were isolating, shielding or unwell [

23,

34]. Where horseracing staff may continue to work whilst experiencing injury, or may return to work early, workplace interventions such as adaptations to tasks and hours, should be implemented as a standard protocol, with modifications implemented on an individual basis, considerate of physical limitations, injury type and pain levels. These adaptations should be monitored closely and return to work should be contingent on reduced workload subject to doctors’ approval.

Work friends, parents, and employers were viewed as both positive and negative support mechanisms whilst coping with injury, which reflects previous sport & occupational health literature [

28,

89,

92]. Social support, such as from employers, friends, family, or colleagues, is particularly important in maintaining adherence to rehabilitation, and disengagement can lead to feelings of isolation, which decreases adherence to rehabilitation [

93,

94]. Udry et al. [

95] suggested more athletes reported negative social support than positive, whilst 54% of unhelpful supporters are typically family members [

96]. Comparatively, in military personnel, home-based social support (including family members) has been shown to be a protective factor for veterans at risk of suicide [

97]. Interestingly, Tveito et al. [

87] found that workers were concerned about being too vocal in complaints of pain at work due to fear of annoying colleagues, which has been seen here in this study, with staff reporting concern over “embarrassment”, “looking weak”, “being a nuisance” or “being seen as soft”. Research suggests that post-trauma, negative social support, such as criticism or indifference to the wellbeing of that person, has a greater impact on successful recovery outcomes than lack of support [

28].

The quality of the relationship can influence perception of support more than the nature of the relationship between individuals [

92], and open communication between employers and employees is recognized as critical to a successful return to work following injury by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [

89]. Open communication is a key managerial skill, something reported as lacking within the horseracing sector, whereby staff are often promoted to management level due to horsemanship skills rather than people skills [

17]. Management behaviour have also been found to be a key factor in influencing how employees handle pain at work [

98,

99]. Within the racing industry, 44% of employees previously stated that their employer was “not supportive at all” in response to their injury rehabilitation, which could affect rehabilitation success and recovery in stable staff, and mirrors the results shown in this study (41%) [

10] (pp. 39). Trauma within the workplace can also create a distrust in senior staff, who are entrusted with care of employees and a sense of betrayal may be formulated here which can further affect communication between staff and employees and exaggerate the underreporting of work-based injuries previously seen in this population [

7,

9,

10,

28]. The disparity seen here in whether employers are supportive during the injury process may stem from ineffective people management practices in horseracing yards, and highlights a need for specialized, targeted managerial training to support staff who are promoted to senior management [

17,

24].

Under the U.K. national legislative framework, the employer has a responsibility to manage employee risk at work, including taking measures to control risk, therefore managerial or senior staff are critical in successful injury management within racing yards [

23]. Whilst there has been an increasing amount of guidance available for employers on mental health in the workplace in recent years, there is still a lack of guidance on musculoskeletal pain and injury available [

89]. Palsson et al. [

100] identified that educational resources for organisations could reduce pain-related loss of workability and fostering cultures of open communication with staff could decrease absenteeism in the workforce, whilst both training and targeted organizational campaigns were found to have a positive effect on injury reduction globally [

24]. The Racing Occupational Health Service offers workplace talks as part of their suite of services [

26], however, these resources are relatively new within the industry, and according to this survey are underutilized. Furthermore, as OHS provision is voluntary within the U.K., the responsibility for promotion of available services lies with the employer, suggesting that racing staff may not be accessing Racing Welfare’s suit of services as they are not being directed to them by their employer when required. Further development of Racing Welfare’s educational resources, particularly targeted to employers to highlight the economic, performance and productivity benefits for OHS provision in the workplace [

21,

22,

23,

24] would be greatly beneficial to maintaining the health and wellbeing of the workforce in horseracing.

4.3. Attitudes to Injury and Injury Reporting Behaviours

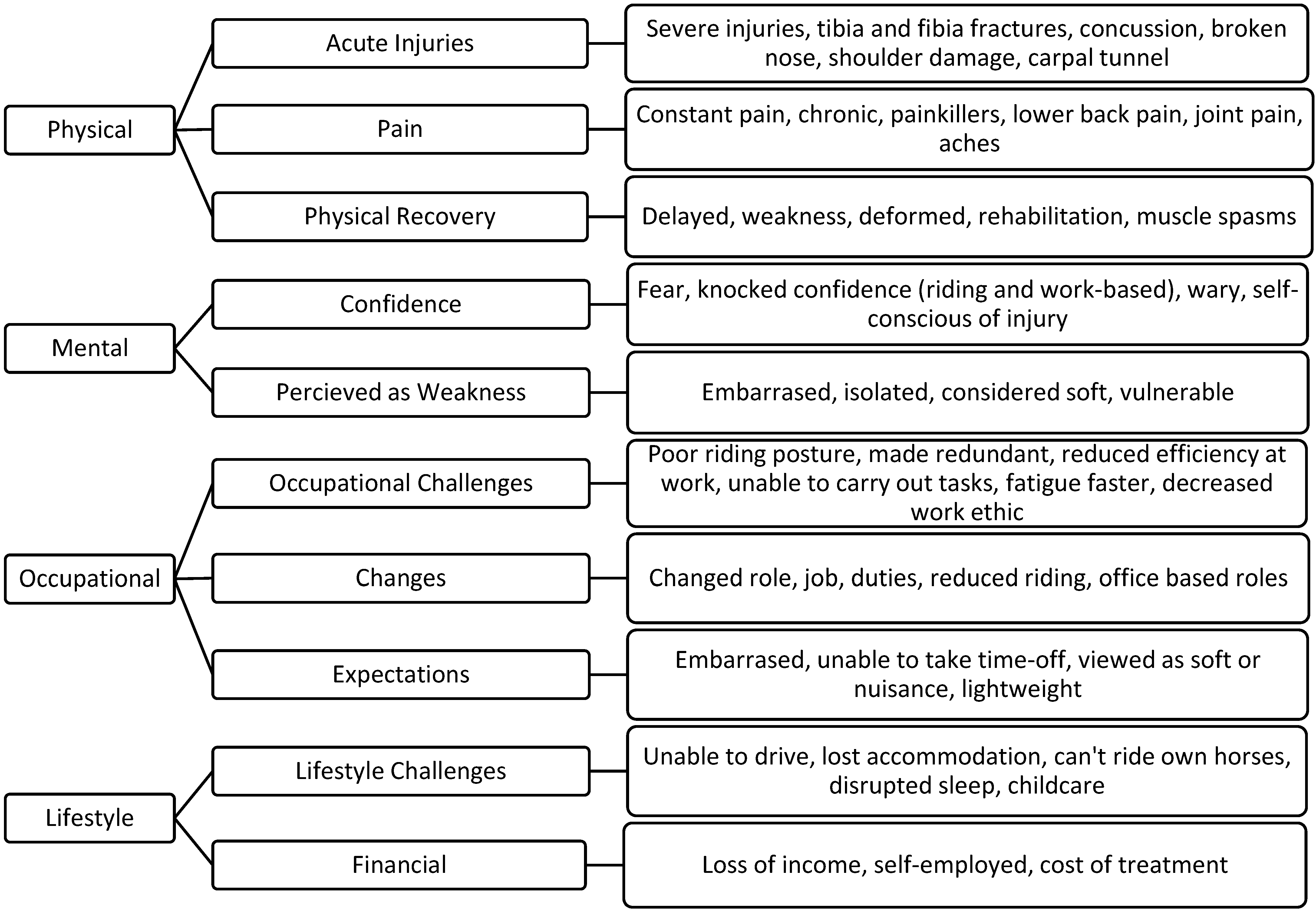

The results of this study indicate presenteeism is seen in horseracing, and there was a tendency for staff to underreport occupational injuries to their employer. Attitudes towards injury reporting behaviours in this study were influenced by a range of sociocultural and occupational factors, including perceived industry expectations, financial circumstances, previous experiences of injury, staffing structure and perceived employer expectations.

Injury reporting has previously been considered a concern in the racing industry, with anecdotal reports of staff unwilling to take sick leave or continuing to work despite chronic pain or injury [

2,

7,

9,

10]. Staff often cite a love of the job, moral or ethical obligations (for example to animal welfare), or concerns for job security as reasons for not taking adequate time off [

10,

101]. Underreporting of injuries, or not seeking subsequent medical intervention, has also been seen in wider equestrian sports [

102], whereby injury is seen as something that cannot be avoided but should not delay or prevent engagement with equestrian activities [

75], suggesting there may be a cultural connotation with injury attitudes in horse-related industries, rather than solely within horseracing. In other animal care industries, presenteeism is often associated with guilt, as well as concern that animal welfare is being impacted by their absence [

18], resulting in continuing to work despite injury or illness. Within horseracing, the requirements to maintain high standards of care of the horses is vital for the success of training yards, and if injured staff prioritize their own needs and career ahead of daily management and care of the horses in their care, they may experience guilt, linked to both equine welfare and perhaps their colleagues who are taking on additional work.

Employees may also reduce reporting behaviour to avoid guilt for letting the team down, which has been seen in injured athletes [

103,

104,

105]. Within the racing industry, there is currently a staff shortage, which can lead to issues with being covered if off sick or injured [

9,

67,

68]. Different to the psychological belief that an employee is irreplaceable [

18], the current working conditioning within racing highlights a physical lack of staff who can cover shifts. This was highlighted as a concern for trainers in Sear’s [

9] study, whereby finding staff cover was reported as a main source of stress for those working in industry. Injury has been previously highlighted as a significant source of stress for managerial or coaching staff, who are in positions of responsibility to ‘fill the gaps left by injury’ within a team, much the same as a trainer [

9,

106]. If this stress is made known, directly, or indirectly, to a team of subordinates, that team may alter their behaviours, and subsequently hide injuries or pain, to reduce stress on their manager, particularly where good relationships have been developed. Many staff in this study highlighted a pressure to continue working, either related to their employer (don’t want to hassle them, not necessary), to other staff (burden on other staff) or to the horses themselves (horses need me).

However, in this study, some staff did identify a clear injury reporting protocol, and stressed the importance of following this in their own practice (and influencing others to do the same) to maintain staff health and wellbeing. In both horseracing and equestrian sport, horsemanship skills are typically learnt in apprenticeship positions [

20] and in deference towards those with greater equine experience [

17,

75], thus attitudes to injury are often ‘taught’ through peer-to-peer interaction [

107]. This could suggest that whilst injury minimalization culture is a concern in horseracing [

16], its prevalence and impact on injury reporting may be subject to individual yard microcultures, rather than a comprehensive industry-wide problem. Further research should consider the role of individual yard culture on injury reporting practices, and design educational intervention packages to reduce the stigma associated with injury and increase awareness of the implications of injury denial on employee health and wellbeing.

Whilst there are many factors that can affect reporting behaviour in occupational settings, an increase in injury severity typically results in improved reporting behaviours [

107], however, that relationship is not seen here with respect to concussion. Staff were more likely to seek medical attention and report injuries to their employer for visible injuries, such as fractures, compared to suspected concussion or other musculoskeletal injuries. Underreporting of concussion has been identified as a common issue in athletic populations, and it is believed that many sport concussions go unreported and undiagnosed due to limited disclosure of symptoms from athletes [

108,

109]. Common reasons for hiding symptoms includes downplaying severity, loss of athletic standing amongst coaches or peers [

108] and prior experiences of concussion resulting in belief of ‘knowing oneself’ and limits of capability linked to the current concussion [

109]. Downplaying the severity of injuries could be attributed to injury denial [

110,

111], which is one of the five stages of grief commonly attributed to athlete injury during the emotional response phase [

37]. Denial often results in emotional instability following injury [

93], and difficulty coping with stress [

112], which could result in risk of reinjury, as well as impact workplace retention and career longevity.

Horseracing has previously been at the forefront of concussion protocols for jockeys since 2003 with the introduction of the British Horseracing Authority’s (BHA) standardized concussion protocol [

20], however, this study would suggest that the self-management of concussion for staff on training and stud yards is suboptimal. Whilst most research suggests the need to enhance concussion education for athletes and coaches, or in this instance, staff and trainers [

10,

109], Conway et al. [

108] suggested that there was no relationship between lack of concussion knowledge in athletes and underreporting behaviours, in fact higher knowledge often related to enhanced ability to hide symptoms. National targeted media strategies highlighting the reasons why athletes should disclose concussion, as well as the implications for non-disclosure on health, finances, and support networks (family, friends, spouse, children) is equally important to increasing reporting behaviours in sport [

108]. Horseracing has previously used several major national campaigns to promote healthy behaviour in professional jockeys, such as the 2016 Jockey Matters campaign run by the Jockey Education and Training Scheme (JETS) [

113], which provided educational resources and helplines offering support on nutrition, physical fitness, injury and concussion and mental health. Stable staff recently highlighted the need for such resources [

10] despite some already being provided through Racing Welfare. A national campaign to promote concussion awareness, alongside standard protocols for stud and stable staff are the next steps for the industry to tackle workplace concussion.

Within this study, women were less likely to report musculoskeletal injuries to their employer, as well as less likely to seek medical attention and take time off compared to male counterparts. Wider research in Sweden has identified that the highest rates of underreporting occupational injuries were seen in female dominated organisations [

107], whilst culturally, men are more likely to engage in risk taking behaviour which is causally linked to injury incidence [

78]. Male athletes have also been found to affiliate with hypermasculine ideologies, such as indifference to physical pain, which has been found to be a predictor in negative attitudes to seeking help [

114]. Within the racing industry, significant strides have been made regarding gender equality, with current estimations of a 70:30 split (female to male) on racing yards [

115], however, there are still some residual perceived sex imbalances which can act as key barriers for women in racing to advance in the industry [

115,

116,

117]. As a result of the potential gender biases within the workforce culture in racing, female staff may be less likely to report injuries compared to their male counterparts for fear of being viewed as weaker [

117]. Employers within the racing industry should be conscious that female staff may be more likely to report injury behaviours differently to their male counterparts [

107].