Initiatives Addressing Precarious Employment and Its Effects on Workers’ Health and Well-Being: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Links between PE, Non-Standard Employment (NSE), and Informal Work

1.2. Factors Contributing to the Rise in NSE and Implications for PE

1.3. Significance of PE to Public Health

1.4. Review Justification, Contribution, Objectives, and Approach

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- (i)

- Editorial, commentary, discussion paper, review.

- (ii)

- No clear initiative implemented.

- (iii)

- Initiatives designed to:

- Facilitate PE or increase exposure to PE.

- Improve workers’ health through individual behavioural change without a focus on PE.

- Improve work performance or health, safety, or well-being of workers with disabilities without a focus on PE.

- Eliminate or reduce workers’ exposure to unemployment.

- Eliminate, reduce, or mitigate the effects of unemployment on health and well-being.

- Promote workers’ return to work after illness or injury without addressing PE.

- (iv)

- Initiatives not evaluated formally or assessed using empirical data or initiatives with an evaluation that does not include a clear focus on reduction in precarious employment and/or on precarious workers and/or their families.

- (v)

- Not in a language covered by the members of this team, mentioned for inclusion in the review protocol (Catalan, Danish, Dutch, French, Italian, Norwegian, Romanian, Spanish, and Swedish).

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Qualitative Assessment

2.5. Presentation of Results

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Included Studies

3.2. Study and Initiative Characteristics

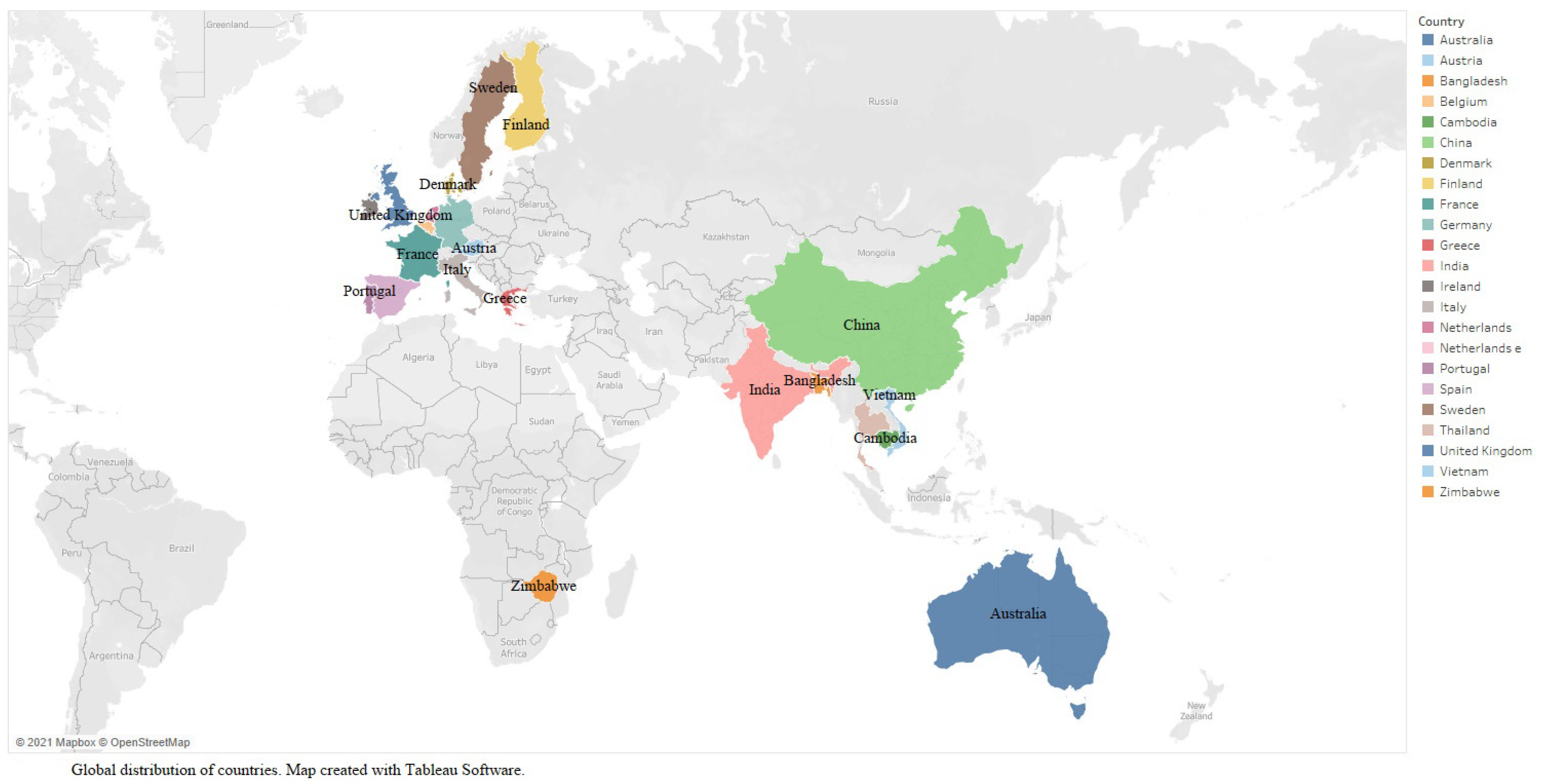

3.2.1. Countries Examined, Type of Evidence, Study Design, Targeted Economic Sector, and Population Sub-Groups

3.2.2. Description of Initiatives, Ways in Which They Could Impact PE, and Design and Data Collection Approaches Used to Evaluate Them

3.3. Health and Well-Being Outcomes

3.3.1. Occupational Health and Safety

3.3.2. Health and Well-Being

3.4. Facilitators and Barriers

3.5. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Practice Implications

4.2. Research Implications

4.3. Policy Implications

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matilla-Santander, N.; Ahonen, E.; Albin, M.; Baron, S.; Bolíbar, M.; Bosmans, K.; Burström, B.; Cuervo, I.; Davis, L.; Gunn, V.; et al. COVID-19 and Precarious Employment: Consequences of the Evolving Crisis. Int. J. Health Serv. 2021, 51, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilla-Santander, N.; Lidón-Moyano, C.; González-Marrón, A.; Bunch, K.; Sanchez, J.C.M.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M. Measuring precarious employment in Europe 8 years into the global crisis. J. Public Health 2019, 41, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C.; Solar, O.; Santana, V.; Quinlan, M. Introduction to the WHO commission on social determinants of health employment conditions network (EMCONET) study, with a glossary on employment relations. Int. J. Health Serv. 2010, 40, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadden, W.C.; Muntaner, C.; Benach, J.; Gimeno, D.; Benavides, F.G. A glossary for the social epidemiology of work organisation: Part 3, Terms from the sociology of labour markets. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntaner, C.; Benach, J.; Hadden, W.C.; Gimeno, D.; Benavides, F.G. A glossary for the social epidemiology of work organisation: Part 2. Terms from the sociology of work and organisations. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, M.; Benach, J.; Muntaner, C.; Amable, M.; O’Campo, P. Is precarious employment more damaging to women’s health than men’s? Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C. Precarious employment and health: Developing a research agenda. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-H.; Khang, Y.-H.; Muntaner, C.; Chun, H.; Cho, S.-I. Gender, precarious work, and chronic diseases in South Korea. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2008, 51, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benach, J.; Vives, A.; Amable, M.; Vanroelen, C.; Tarafa, G.; Muntaner, C. Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreshpaj, B.; Orellana, C.; Burström, B.; Davis, L.; Hemmingsson, T.; Johansson, G.; Kjellberg, K.; Jonsson, J.; Wegman, D.H.; Bodin, T. What is precarious employment? A systematic review of definitions and operationalizations from quantitative and qualitative studies. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2020, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, T.; Caglayan, C.; Garde, A.H.; Gnesi, M.; Jonsson, J.; Kiran, S.; Kreshpaj, B.; Leinonen, T.; Mehlum, I.S.; Nena, E.; et al. Precarious employment in occupational health—An OMEGA-NET working group position paper. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2020, 46, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calenda, D.; Return Migration and Development Platform (RDP); Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS); European University Institute (EUI). Investigating the Working Conditions of Filipino and Indian-Born Nurses in the UK; ILO Country Office for the Philippines: Makati City, Philippines, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Casual Work: Characteristics and Implications; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C.; Santana, V.; Employment Conditions Knowledge Network (EMCONET). Employment Conditions and Health Inequalities. Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health; Employment Conditions Knowledge Network (EMCONET), Pompeu Fabra University: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Lewchuk, W. Collective bargaining in Canada in the age of precarious employment. Labour Ind. 2021, 31, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization-Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health—Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Renard, K.; Cornu, F.; Emery, Y. The impact of new ways of working on organizations and employees: A systematic review of literature. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julià, M.; Tarafa, G.; O’Campo, P.; Muntaner, C.; Jódar, P.; Benach, J. Informal employment in high-income countries for a health inequalities research: A scoping review. Work 2015, 53, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILO. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, 3rd ed.; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Whitehead, D.; Ghellab, Y.; Muñoz de Bustillo Llorente, R. (Eds.) The New World of Work: Challenges and Opportunities for Social Partners and Labour Institutions; Edward Elgar Publishing & International Labour Office: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muntaner, C.; Ng, E.; Gunn, V.; Shahidi, F.V.; Vives, A.; Finn Mahabir, D.; Chung, H. Precarious employment conditions, exploitation, and health in two global regions: Latin America and the Caribbean and East Asia. In Handbook of Socioeconomic Determinants of Occupational Health. Handbook Series in Occupational Health Sciences; Theorell, T., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, B.; Hünefeld, L. Temporary Agency Work and Well-Being—The Mediating Role of Job Insecurity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. World Social Protection Report 2020–2022. Social Protection at the Crossroads-in Pursuit of a Better Future; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, J.; Muntaner, C.; Bodin, T.; Alderling, M.; Balogh, R.; Burström, B.; Davis, L.; Gunn, V.; Hemmingsson, T.; Julià, M.; et al. Low-quality employment trajectories and risk of common mental disorders, substance use disorders and suicide attempt: A longitudinal study of the Swedish workforce. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilla-Santander, N.; González-Marrón, A.; Martín-Sánchez, J.C.; Lidón-Moyano, C.; Hueso, À.C.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M. Precarious employment and health-related outcomes in the European Union: A cross-sectional study. Crit. Public Health 2019, 30, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnblad, T.; Grönholm, E.; Jonsson, J.; Koranyi, I.; Orellana, C.; Kreshpaj, B.; Chen, L.; Stockfelt, L.; Bodin, T. Precarious employment and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2019, 45, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulford, A.; Thomson, R.; Popham, F.; Leyland, A.; Katikireddi, S.V. Does Persistent Precarious Employment Affect Health Outcomes among Working Age Adults? Prospero CRD42019126796; National Institute for Health Research: York, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lewchuk, W.; Clarke, M.; de Wolff, A. Working without commitments: Precarious employment and health. Employ. Soc. 2008, 22, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koranyi, I.; Jonsson, J.; Rönnblad, T.; Stockfelt, L.; Bodin, T. Precarious employment and occupational accidents and injuries—A systematic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2018, 44, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrin-Petersen, R.; Bolko, I.; Hlebec, V. The Effects of Precarious Employments on Subjective Wellbeing: A Meta-Analytic Review; PROSPERO CRD42019140288; National Institute for Health Research: York, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lewchuk, W. Precarious jobs: Where are they, and how do they affect well-being? Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2017, 28, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn Ahonen, E.; Fujishiro, K.; Cunningham, T.; Flynn, M. Work as an inclusive part of population health inequities research and prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgard, S.; Lin, K.Y. Bad jobs, bad health? How work and working conditions contribute to health disparities. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1105–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.H.; Khang, Y.H.; Cho, S.I.; Chun, H.; Muntaner, C. Gender, professional and non-professional work, and the changing pattern of employment-related inequality in poor self-rated health, 1995–2006 in South Korea. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2011, 44, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntaner, C.; Chung, H.; Solar, O.; Santana, V.; Castedo, A.; Benach, J.; Network, E. A macro-level model of employment relations and health inequalities. Int. J. Health Serv. 2010, 40, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewchuk, W.; Procyk, S.; Laflèche, M.; Dyson, D.; Goldring, L.; Shields, J.; Viducis, P. Getting Left Behind: Who Gained and Who Didn’t in an Improving Labour Market; Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario (PEPSO), McMaster University & United Way Greater Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C.; Solar, O.; Santana, V.; Quinlan, M.; Network, E. Employment, Work and Health Inequalities: A Global Perspective; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.-M.; Chang, J.; Won, E.; Lee, M.-S.; Ham, B.-J. Precarious employment associated with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in adult wage workers. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 218, 201–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-Y.; Jang, S.-I.; Bae, H.-C.; Shin, J.; Park, E.-C. Precarious employment and new-onset severe depressive symptoms: A population-based prospective study in South Korea. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2015, 41, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, E.-C.; Lee, T.-H.; Kim, T.H. Effect of working hours and precarious employment on depressive symptoms in South Korean employees: A longitudinal study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 73, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.; Reeves, A.; Clair, A.; Stuckler, D. Living on the edge: Precariousness and why it matters for health. Arch. Public Health 2017, 75, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julià, M.; Vanroelen, C.; Bosmans, K.; Van Aerden, K.; Benach, J. Precarious employment and quality of employment in relation to health and well-being in Europe. Int. J. Health Serv. 2017, 47, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Kim, C.-Y.; Park, J.-K.; Kawachi, I. Is precarious employment damaging to self-rated health? Results of propensity score matching methods, using longitudinal data in South Korea. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1982–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.-Y.; Park, S.-G.; Hwang, S.H.; Min, K.-B. Disparities in precarious workers’ health care access in South Korea. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 59, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, J.; Matilla-Santander, N.; Kreshpaj, B.; Orellana, C.; Johansson, G.; Burstrom, B.; Aldering, M.; Pedkham, T.; Kjellberg, K.; Selander, J.; et al. Exploring multidimensional operationalizations of precarious employment in Swedish register data—A typological approach and a summative score approach. Scand J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, F.G.; Benach, J.; Muntaner, C. Associations between temporary employment and occupational injury: What are the mechanisms? Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, A.; Amable, M.; Ferrer, M.; Moncada, S.; Llorens, C.; Muntaner, C.; Benavides, F.G.; Benach, J. The Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES): Psychometric properties of a new tool for epidemiological studies among waged and salaried workers. BMJ Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, J.; Vives, A.; Benach, J.; Kjellberg, K.; Selander, J.; Johansson, G.; Bodin, T. Measuring precarious employment in Sweden: Translation, adaptation and psychometric properties of the Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES). BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Measuring Precarious Work; A working paper of the EINet Measurement Group; University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Premji, S.; Shakya, Y.; Spasevski, M.; Merolli, J.; Athar, S.; Immigrant, W.; Immigrant Women and Precarious Employment Core Research Group. Precarious work experiences of racialized immigrant woman in Toronto: A community-based study. Just Labour 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarström, A.; Virtanen, P.; Janlert, U. Are the health consequences of temporary employment worse among low educated than among high educated? Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 21, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, S.A. Self-employment in times of crisis: The case of the Spanish financial crisis. Economies 2019, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. The Illusions of Entrepreneurship: The Costly Myths that Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Policy Makers Live by; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower, D.G. Self-Employment: More May Not Be Better; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kepler, E.; Shane, S.A. Are Male and Female Entrepreneurs Really that Different? An Office of Advocacy Working Paper; SBA Office of Advocacy: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, B.; Grey, C.; Hookway, A.; Homolova, L.; Davies, A. Differences in the impact of precarious employment on health across population subgroups: A scoping review. Perspect. Public Health 2021, 141, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdorf, A.; Porru, F.; Rugulies, R. The COVID-19 pandemic: One year later—An occupational perspective. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2021, 47, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delphine, S. Covid Crisis Threatens UK Boom in Self-Employed Work; FT.com: Financial Times (Nikkei): London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, 29–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, V.; Håkansta, C.; Vignola, E.; Matilla-Santander, N.; Kreshpaj, B.; Wegman, D.H.; Hogstedt, C.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Muntaner, C.; Baron, S.; et al. Initiatives addressing precarious employment and its effects on workers’ health and well-being: A protocol for a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, V.; Håkansta, C.; Vignola, E.; Matilla-Santander, N.; Kreshpaj, B.; Wegman, D.; Hodgstedt, C.; Quinn Ahonen, E.; Muntaner, C.; Baron, S.; et al. Systematic Review of Implemented and Evaluated Initiatives to Eliminate, Reduce, or Mitigate Workers’ Exposure to Precarious Employment and/or Its Effects on the Physical and Mental Health, Health Equity, Safety, and Well-Being of Workers and Their Families. PROSPERO Registration 2020 CRD42020187544; International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; National Institute for Health Research (NIHR): London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Hong, Q.N.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A.; Pluye, P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 49–59.e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R. The Impact of Globalization on Local Communities: A Case Study of the Cut-Flower Industry in Zimbabwe. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/africa/information-resources/publications/WCMS_228866/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Salvatori, A. Labour contract regulations and workers’ wellbeing: International longitudinal evidence. Labour Econ. 2010, 17, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.; Anema, J.R.; Schellart, A.J.M.; Knol, D.L.; van Mechelen, W.; van der Beek, A.J. A participatory return-to-work intervention for temporary agency workers and unemployed workers sick-listed due to musculoskeletal disorders: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2011, 21, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bowman, J.R.; Cole, A.M. Cleaning the ‘people’s home’: The politics of the domestic service market in Sweden. Gend. Work Organ. 2014, 21, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manothum, A.; Rukijkanpanich, J. A participatory approach to health promotion for informal sector workers in Thailand. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2010, 2, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rothboeck, S.; Comyn, P.; Banerjee, P.S. Role of recognition of prior learning for emerging economies: Learning from a four sector pilot project in India. J. Educ. Work 2018, 31, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.A.M.; Ahmed, S.; Sultana, M.; Sarker, A.R.; Chakrovorty, S.; Rahman, M.H.; Islam, Z.; Rehnberg, C.; Niessen, L.W. The effect of a community-based health insurance on the out-of-pocket payments for utilizing medically trained providers in Bangladesh. Int. Health 2020, 12, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.; Dehejia, R.; Robertson, R. Regulations, monitoring and working conditions: Evidence from Better Factories Cambodia and Better Work Vietnam. In Creative Labour Regulation; McCann, D., Lee, S., Belser, P., Fenwick, C., Howe, J., Luebker, M., Eds.; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Orchiston, A. Precarious or protected? Evaluating work quality in the legal sex industry. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W. Public health insurance and the labor market: Evidence from China’s Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance. Health Econ. 2021, 30, 403–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, T.; Tong, L.; Kannitha, Y.; Sophorn, T. Participatory approach to improving safety, health and working conditions in informal economy workplaces in Cambodia. Work 2011, 38, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benach, J.; Vives, A.; Tarafa, G.; Delclos, C.; Muntaner, C. What should we know about precarious employment and health in 2025? Framing the agenda for the next decade of research. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migrationsverket; Arbetsförmedlingen; Skatteverket; Ekobrottsmyndigheten; Jämställdhetsmyndigheten; Polisen; Försäkringskassan; Arbetsmiljöverket. Status Report 2020 for the Inter-Agency Work against Fraud, Rule Violations and Crime in Working Life; Swedish Migration Agency: Boden, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Collyer, T.A.; Smith, K.E. An atlas of health inequalities and health disparities research: “How is this all getting done in silos, and why?”. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 264, 113330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérastégui, P. Exposure to Psychosocial Risk Factors in the Gig Economy: A Systematic Review; European Trade Union Institute: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell, C.; Muntaner, C.; Benach, J.; Artazcoz, L. Social class and self-reported health status among men and women: What is the role of work organisation, household material standards and household labour? Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1869–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Platform Economy Repository; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, L.; Golden, S.D.; Earp, J.A.L. Structural Approaches to Health Promotion: What Do We Need to Know About Policy and Environmental Change? Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 40, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntaner, C.; Ng, E.; Chung, H. Better Health: An Analysis of Public Policy and Programming Focusing on the Determinants of Health and Health Outcomes That Are Effective in Achieving the Healthiest Populations; Canadian Health Services Research Foundation & CNA: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.N.; Wigley, S.; Holmer, H. Implementation of non-communicable disease policies from 2015 to 2020: A geopolitical analysis of 194 countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1528–e1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Initiatives to Improve Conditions for Platform Workers: Aims, Methods, Strengths and Weaknesses; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.G.; Morrow, R.H.; Ross, D.A. Field Trials of Health Interventions: A Toolbox, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Studies Included | 11 | |

|---|---|---|

| Continents represented by the countries examined | Africa | 1 |

| Asia | 6 | |

| Europe | 3 | |

| Oceania | 1 | |

| Study design * | Qualitative studies | 5 |

| Randomized controlled trials | 1 | |

| Non-randomized controlled trials | 1 | |

| Quantitative descriptive studies | 3 | |

| Mixed methods studies | 1 | |

| Targeted economic sector (ISIC Rev 4) **, ° | Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing | 3 |

| Manufacturing | 4 | |

| Construction | 2 | |

| Hotels and restaurants | 1 | |

| Transportation and storage | 1 | |

| Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods- and services-producing activities of households for own use | 2 | |

| Not elsewhere classified | 1 | |

| All economic sectors | 2 | |

| Initiative being purposefully designed to address precarious employment | No | 10 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Dimensions of PE potentially impacted ° | Employment insecurity | 4 |

| Lack of rights and protection in the employment relation | 5 | |

| Income inadequacy | 4 | |

| Health and well-being outcomes evaluated ° | Occupational health and safety | 7 |

| Worker and/or family health and well-being | 6 | |

| Quality appraisal rating *** | Low quality (0 to 2) | 1 |

| Medium quality (3 to 5) | 6 | |

| High quality (6 to 7) | 4 | |

| Study Author(s) Publication Year | Countries Examined | Type of Evidence | Study Design | Targeted Economic Sector and Population Sub-Groups | Study Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davies R., 2000 [67] | Zimbabwe | ILO institutional report | Qualitative study (Case study) | Agriculture Formal and informal flower-growing workers | To examine the impact of international labelling standards adopted by the flower-growing farmers in Zimbabwe on employment, income, and working conditions. |

| Manothum, A. et al., 2010 [71] | Thailand | Academic journal article | Qualitative study (Participatory action research) | Ceramic workers, plastic weavers, blanket makers, and pandanus weavers Informal sector workers | To evaluate the outcomes of a participatory approach used to promote OHS, based on informal sector workers’ (a) knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours in OHS, (b) work practice improvements, and (c) working conditions improvements. |

| Salvatori, A., 2010 [68] | 13 OECD countries: Austria, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, UK, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal | Academic journal article | Quantitative descriptive study (Longitudinal panel surveys) | No specific sector Permanent and temporary workers affected by employment protection legislation | To study the effects of employment protection legislation adopted for permanent workers and of restrictions on the use of temporary employment on individual workers’ wellbeing. |

| Kawakami, T. et al., 2011 [77] | Cambodia | Academic journal article | Qualitative study (Participatory action research) | Domestic service sector, small construction sites, rural farms Informal workers | To examine the impact of a participatory approach and use of participatory training methodologies on safety and health in informal workplaces. |

| Vermeulen, S.J. et al., 2011 [69] | Netherlands | Academic journal article | Randomized controlled trial | No specific sector Temporary and unemployed agency workers sick-listed due to musculoskeletal disorders | To evaluate the effectiveness of a participatory return-to-work program to facilitate work resumption and reduce work disability for unemployed workers and temporary agency workers, who are off on sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders. |

| Bowman, J.R et al., 2014 [70] | Sweden | Academic journal article | Qualitative study (Case study) | Domestic service sector Cleaning workers, both formal and informal | To describe the impact of a governmental tax policy that subsidizes the hiring of domestic cleaning workers on the creation of better working conditions for them. |

| Brown, D. et al., 2014 [74] | Vietnam | Book chapter | Quantitative descriptive study (Case study) | Textile industry Factory workers | To conduct a preliminary assessment of the impact of the Better Work Vietnam program on compliance with national and international labour regulations and on factory and worker well-being. Given its focus on compliance and the use of non-primary evidence, the evaluation of the Better Factories Cambodia program, also included in this chapter, is not part of our analysis. |

| Orchiston, A., 2016 [75] | Australia | Academic journal article | Qualitative study (Case study) | Sex industry Brothel-based sex workers | To study the relationship between sex workers’ working conditions and two regulatory models governing sex work (decriminalisation and licencing). |

| Rothboeck, S. et al., 2018 [72] | India | Academic journal article | Mixed methods | Agriculture, Healthcare Gems and jewellery; Domestic sector Workers in sectors with high informality | To examine the impact of the ‘Recognition of Prior Learning’ initiative on income opportunities, occupational safety, social status, and openness to further learning. |

| Khan, J.A.M. et al., 2020 [73] | Bangladesh | Academic journal article | Non-randomized study (Quasi-experimental) | Rickshaw pullers, shopkeepers, restaurant workers, day laborers, factory workers

and transport workers in rural areas Informal workers | To estimate the effect of a community-based health insurance scheme on the magnitude of out-of-pocket healthcare payments made by informal workers and their dependents for health services. |

| Si, W., 2021 [76] | China | Academic journal article | Quantitative descriptive study (Cross-sectional) | No specific sector Urban population not covered by employment-based health insurance. | To estimate the effects of a national public health insurance program on health and on various labour market outcomes such as long-term and limited duration employment, and self-employment. |

| Study Author(s) Year of Publication | Implemented Initiatives Initiative Being Purposefully Designed to Address Precarious Employment | Ways in Which the Initiative Could Impact PE Specific Dimension(s) of PE Potentially Impacted | Initiative Level | Design and Data Collection Approaches Used to Evaluate Initiatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davies, R., 2000 [67] | Flower-growing farmers’ adoption of international standards regulating flower quality and producing methods. Such standards regulate labour, environmental, and social aspects related to the production of flowers. The labour aspects regulated involve collective bargaining, employment security, equal treatment, wage setting processes, health and safety practices, and banning of child labour. The environmental aspects control the use of crop protection agents and fertilizers, energy utilized, disposal of toxic agents, and waste production, while the social aspects controlled include pay levels, living and working facilities, and respecting human rights. No | Eliminate, reduce, or mitigate workers’ exposure to informal employment or PE and their effect on workers’ health and well-being. Employment insecurity | Meso level | Field interviews and surveys conducted with 5 farmers and 34 workers at five farms that adopted labelling standards. Workers were asked to compare health and safety practices and job characteristics with those at previous farms they worked at that did not adapt the standards. Additional information collected from collective bargaining agreements, statistical data, and personal communication with experts in the field. |

| Manothum, A. et al., 2010 [71] | The adoption of aparticipatory process to involve informal workers in addressing and solving occupational health and safety risks to minimize their health effects and prevent them in the long-term. The initiative included capacity building, risk analysis, problem prevention and solving, and monitoring and communication; it was developed in partnership with local networks, non-governmental organizations, governmental officials, and informal worker leaders. No | Mitigate the effect of informal employment on workers’ health and well-being. | Meso level | Evaluation of data collected before and after the implementation of the participatory process approach measuring: (1) knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours, using a questionnaire developed by the Department of Labor in Thailand; (2) work practice improvements, using an ILO-developed checklist; and (3) heat and lighting, using industrial hygiene instruments. |

| Salvatori, A., 2010 [68] | Adoption of employment protection legislation for permanent workers and of restrictions on the use of temporary employment to protect workers with permanent contracts. Differences in the type of legislation adopted across the 13 countries and 7 years analysed. Yes | Limit increases in prevalence of PE. Employment insecurity Lack of rights and protection in the employment relation. | Meso level | Seven waves (1994–2001) of the European Community Household Panel used to collect data on a subjective measure of well-being (job satisfaction) from a large sample of temporary and permanent employees in 13 OECD countries. The exposure variable, employment legislation, measured with two OECD aggregated indicators, an employment protection legislation index and an index assessing restrictions on the use of temporary employment. The outcome of interest measured for both permanent and temporary workers and compared across 13 countries and 7 years, taking advantage of between country and yearly variation in employment protection legislation. |

| Kawakami, T. et al., 2011 [77] | A participatory training program developed collaboratively by the government, employers, NGOs, and workers and delivered by safety and health trainers. Key program steps: (i) the identification of existing health and safety practices; (ii) the development of new participatory training programmes based on ILO training programmes; and (iii) the training of safety and health trainers using a train the trainer model. No | Mitigate the effect of informal employment on workers’ health and well-being. | Micro level | Workplace visits conducted to collect process and outcome indicators such as number of people trained, types of training tools developed, and types of improvements implemented after the adoption of the initiative. |

| Vermeulen, S.J. et al., 2011 [69] | A participatory return-to-work program was developed to make return-to-work for unemployed workers and temporary agency workers more effective. Typically, these workers do not have a workplace or an employer to return to. The sick-listed worker, a labor expert from a social security agency, an independent return-to-work coordinator, and a rehabilitation agency sought solutions to barriers related to physical environments, job and role demands, work experience requirements, commuting, and other factors. This included the finding of a suitable therapeutic workplace for workers to join after their sick leave. No | Promote workers’ return to work after illness or injury in a way that

mitigates their PE. | Micro level | Sick-listed workers were randomly allocated to the participatory return-to-work program or to usual care, consisting of supportive income and rehabilitation support and guidance. Data were collected from a social security agency database and self-report questionnaires completed by workers. Outcomes were measured at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Duration of sickness benefit was defined as the length of time from random allocation to the program until stopping the sickness benefit for at least 28 days. Functional status and general health were assessed through the MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Musculoskeletal pain intensity was evaluated using the Von Korff questionnaire. |

| Bowman, J.R et al., 2014 [70] | Adoption of a tax policy that provides a tax break to households that hire domestic cleaning workers to help with household activities such as cleaning, cooking, childcare, and gardening/yard work. The cash refund, equivalent to 50% of the hiring costs, subsidizes the cost of hiring domestic workers and reduces households’ costs for hiring them. The purpose of the tax break was twofold: to generate entry-level jobs and reduce undeclared labour in the domestic cleaning sector by making domestic labour services affordable for households without them having to bend the rules. No | Eliminate, reduce, or mitigate workers’ exposure to informal employment or PE and their effect on workers’ health and well-being. Employment insecurity Income inadequacy Lack of rights and protection in the employment relation | Macro level | Semi-structured interviews conducted with cleaning workers’ union leaders, employer organizations, a labour union and an advocacy organization representing undocumented workers, employers and employees from a large cleaning firm, journalists, and party politicians to assess perceptions about the job conditions of domestic service sector cleaners after the introduction of the tax policy as compared with their conditions before. |

| Brown, D. et al., 2014 [74] | The adoption of Better Work Vietnam program, aimed at improving employment and working conditions in the apparel business. The program is based on the Better Work global program model of monitoring compliance with existing labour regulations through partnerships between unions, factory management representatives, government, and market stakeholders. The program consists of mandated adherence to national and international labour standards, monitored by the ILO through a 200-question assessment instrument, along with the mandatory formation of a performance improvement working committee, and the performance of assessment visits by official ILO monitors hired locally. No | Eliminate, reduce, or mitigate workers’ exposure to PE and its effects on workers’ health and well-being. Income inadequacy | Meso level | Pre- and post- implementation data on worker demographics, employment and working conditions (wages, relationship with management, communication), and factory level information regarding program adoption collected through worker surveys. The exposure measures used were length of time since the formation of the performance improvement working committee and length of time since the first assessment visit by official monitors. |

| Orchiston, A., 2016 [75] | Adoption of regulatory frameworks, either decriminalisation or licencing, to govern sex work. The decriminalisation of sex work framework analysed included the repeal of most criminal laws concerning commercial sex activities, the categorization of brothels or other establishments where sex work takes place as lawful, and the subjecting of brothels to the same laws governing other legal commercial businesses. The licencing system framework reviewed required that brothels must be licenced and must adhere to strict licencing requirements overseen by a dedicated government agency. In addition, establishment owners and managers must undergo criminal record checks. No | Eliminate, reduce, or mitigate workers’ exposure to PE and its effects on workers’ health and well-being. Employment insecurity Income inadequacy Lack of rights and protection in the employment relation | Macro level | 30 semi-structured interviews with individuals involved in the sex industry (sex workers, brothel managers, key professionals) to evaluate perceptions on brothel sector working conditions and workplace rights, labour practices, and assess various indicators of employment precariousness. Interview data triangulated through content analysis of 54 weblogs. Document analysis of written contracts, codes of conduct, internal communication and signage also performed. Outcomes compared and contrasted across the two legal frameworks reviewed. |

| Rothboeck, S. et al., 2018 [72] | A recognition of prior informal learning initiative meant to promote inclusive skill development and increase employability through (i) facilitating easier access to technical and vocational education and training for informal workers and (ii) increasing flexibility in obtaining skill recognition and certification. The initiative was piloted in four different industries and the government of India, ILO, and representatives in four economic sectors collaborated for the implementation of the pilots. No | Eliminate, reduce, or mitigate workers’ exposure to informal employment or PE and their effect on workers’ health and well-being. Income inadequacy | Meso level | A baseline survey, two sets of follow-up surveys, field visits, and focus discussion groups conducted to assess the design and implementation of the four pilots and their impact on the targeted workers. In total, 3150 individuals recruited. The assessment of worker outcomes before and after (6 and 18 months, respectively) implementation of the pilots. |

| Khan, J.A.M. et al., 2020 [73] | A pilot community-based health insurance scheme implemented within seven administrative units belonging to a worker cooperative in a rural area. The scheme consisted of a package of health and non-health benefits offered to informal workers and family members in exchange for an ongoing membership fee and low co-payments upon accessing services. No | Reduce and mitigate the effect of informal employment on workers’ health and well-being. Lack of rights and protection in the employment relation | Meso level | Structured face-to-face interviews administered to 1292 households (646 insured and 646 uninsured) to estimate differences in out-of-pocket healthcare payments between insured and non-insured households in the 3 months before the survey. Out-of-pocket payments consisted of medical fees, charges for public hospital care, co-payments for health insurance, and the costs for medicine purchases, medical appliances, and diagnostic tests. |

| Si, W., 2021 [76] | A voluntary national public health insurance program implemented to offer coverage to residents in urban regions who do not benefit from employment-based insurance (e.g., the elderly, children, college students, unemployed workers, self-employed, and informally employed). Participation premium fees subsidized to a high degree by the government, but individuals must partially contribute to the premium fees. No | Reduce and mitigate the effect of PE employment on workers’ health and well-being. Lack of rights and protection in the employment relation | Macro level | Panel data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey, the 2004, 2006, 2009, and 2011 waves used to assess enrolment rates of working age individuals in the national health insurance program, along with several employment mobility indicators. A comparison of indicators across cities that adopted and those that did not yet adopt the program was performed, facilitated by a gradual implementation of the program within the country. |

| Study Author(s) Year of Publication | Implemented Initiative Brief Review of Each Implemented Initiative | Health and Well-Being Outcomes Evaluated Divided into 2 Categories: Occupational Health and Safety and Worker and Family Health and Well-Being | PE Outcomes Evaluated Divided into 3 Categories: Employment Insecurity, Income Inadequacy, and Workplace Rights | Quality Appraisal Rating * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davies, R., 2000 [67] | Flower-growing farmers’ adoption of international standards regulating flower quality and producing methods. | Occupational health and safety—Improvements in health maintenance practices such as workers being sent for regular blood tests and check-ups through health clinics. Worker and family health and well-being—Overall self-reported improvements in worker and family welfare. Despite the provision and use of protective equipment, workers closely exposed to chemical agents reported headaches, chest pain, skin rashes, and eye problems. | Employment insecurity—An increase in the number of permanent workers, including female permanent workers, and the replacement of verbal agreements with written employment contracts. Income inadequacy—Higher wages when compared with the wages workers gained while working at other farms. | High |

| Manothum, A. et al., 2010 [71] | The adoption of a participatory process to involve informal workers in addressing and solving occupational health and safety risks. | Occupational health and safety—Increased use of PPE equipment; increases in workers’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours with regard to work safety practices; increased understanding of job safety; and working conditions improvements including reduced exposure to heat and increased lighting to meet governmental standards. | No PE outcomes evaluated. | High |

| Salvatori, A., 2010 [68] | Adoption of employment protection legislation. | Worker health and well-being—For permanent workers, job satisfaction had a positive relationship with employment protection legislation and a negative relationship with restrictions to temporary employment. For temporary workers, job satisfaction had a positive relationship with employment protection legislation covering permanent workers and a negative relationship with increased restrictions to temporary employment. | The initiative addressed PE, but no PE outcomes were evaluated. | Medium |

| Kawakami, T. et al., 2011 [77] | A participatory health and safety training program. | Occupational health and safety—Increased access to action checklists and training tools on the handling of materials and tools, machine operation safety, working at heights, work ergonomics, physical environment hazards (pesticide handling, lighting, ventilation, use of PPE) and welfare facilities (drinking water, resting facilities, toilets). A total of 5111 workers trained on various strategies to improve safety and work environment conditions. | No PE outcomes evaluated. | Medium |

| Vermeulen, S.J. et al., 2011 [69] | A participatory return-to-work program to facilitate work resumption and reduce work disability, among unemployed workers and temporary agency workers. | Worker health and well-being—No significant differences found between workers in the intervention and usual care comparison groups with regard to functional status, pain intensity, perceived health, and duration of sickness benefit. | No PE outcomes evaluated. | High |

| Bowman, J.R et al., 2014 [70] | Adoption of a tax policy that provides a tax break to households that hire domestic cleaning workers. | Occupational health and safety—Workers benefited from training or information provided by domestic cleaning companies with regard to ergonomics while conducting cleaning work, safety labels, and environmental certification of cleaning products. | Employment insecurity—Improvements in job security given that workers moved from an informal job or from being self-employed to being formally employed by a documented company created as a result of increased demand for cleaning services after the introduction of the tax. Income inadequacy—Wage increases for workers belonging to unionized cleaning companies. Workplace rights—Improvements in union membership and collective agreement coverage, increased access to social insurance benefits, protection against customer abuse, and increased access to training and upward mobility for workers in large cleaning companies. | Low |

| Brown, D. et al., 2014 [74] | The adoption of Better Work Vietnam program, aimed at improving employment and working conditions in the in the apparel business. | Occupational health and safety—No significant relationship was observed between the two exposure measures and factors such as exposure to extreme temperatures, concerns about dangerous equipment, and accidents and injuries. The length of time since first assessment visit by official monitors was associated with perceptions of higher quality of the health clinics offered by the factory. Worker health and well-being—The length of time since the performance improvement working committee was created was associated with increased access to free medicine and with more concerns about the quality of the health clinics provided by the factory. | Income inadequacy—Small and non-statistically significant wage improvements. | Medium |

| Orchiston, A., 2016 [75] | Adoption of regulatory frameworks, either decriminalisation or licencing, to govern sex work. | Occupational health and safety—The decriminalisation approach was comparatively less effective in promoting adherence to occupational health and safety legislation than the licencing framework, which incorporates mandatory safety obligations as part of its licencing requirements. However, effective supervision is needed for any of these models to be effective. | Employment insecurity—Neither of the two regulatory models studied was successful in addressing the problems of bogus self-employment and dismissal. Workplace rights -Licencing promoted stronger compliance with occupational health and safety law than decriminalisation but inefficient supervision reduced the effect on PE for both. - Neither of the two regulatory models studied was successful in enforcing a minimum standard of fair working conditions. | Medium |

| Rothboeck, S. et al., 2018 [72] | An initiative to recognize workers’ prior informal learning. | Occupational health and safety—Increased awareness of occupational health and safety issues and application of safety practices across all four industry sectors examined, with the most improvements observed in the agriculture and gems/jewellery sectors. | Income inadequacy—No significant wage improvements. Although 4% of workers reported a positive effect on their income at both 6 and 18 months and 26% of workers reported some improvements either at 6 or 18 months, the improvements were short-term only and potentially linked to other factors. | Medium |

| Khan, J.A.M. et al., 2020 [73] | A pilot community-based health insurance scheme. | Worker and family health and well-being—Insured households, when compared to uninsured ones were 1.43% more likely to utilize medically trained professionals and their overall out-of-pocket payments for health services provided by medically trained professionals were 6.4% lower. No significant differences found in the overall out-of-pocket payments for health services provided by other types of healthcare providers, both trained and untrained. An individual’s asset quintile, residential location, illness type and inpatient care utilization had a significantly positive effect on out-of-pocket payments. Being unmarried had a significantly negative effect on out-of-pocket payments. | Workplace rights—Improvements in access to social and health benefits. | High |

| Si, W., 2021 [76] | A voluntary national public health insurance program. | Worker health and well-being—A health improvement effect was suggested by the finding that previously unhealthy individuals had an increased probability of being in fixed-term contracts and in self-employment after enrolment in the insurance program. Enrolment rates in the national health insurance program were: (i) similar among self-reported healthy and unhealthy groups, (ii) slightly higher among men than among women, and (iii) higher among individuals who were not working previously or who worked in the informal sector than among those working in the formal sector. | Workplace rights—Improvements in access to social and health benefits. | Medium |

| Barriers | |

|---|---|

| Macro | The extent of the informal economy and the large number of informal workers in some countries are difficult to tackle unless structural, high-level solutions are considered [77]. |

| Market forces sustaining demand for an informal economy and informal workers make it difficult to reduce the informal economy [70]. | |

| Lack of national standards to regulate certain employment and working conditions, lack of enforcement of such standards, and lack of local inspectorates to perform inspections when international standards are adopted [67]. | |

| Low, seasonal, and inconsistent enrolment in large health insurance schemes affects their viability [73]. | |

| Meso | Low density of unions and other forms of organized labour movements within some industries [70,75]. |

| Inadequate or insufficient resources to enforce labour standards within organizations [74]. | |

| Low compliance with minimum labour standards and occupational health and safety requirements in less regulated industries strongly influenced by market forces [75]. | |

| Difficulties encountered with the piloting of initiatives due to insufficient knowledge about their nature and reluctance by both employers and workers to participate [72]. | |

| Lack of accurate baseline data [72]. | |

| Acknowledging and/or addressing only some of the identified problems affecting workers [69]. | |

| Stigma associated with certain industries (e.g., sex work) prevents workers from filing complaints or making use of legal processes to help them challenge situations in which their rights are not met [75]. | |

| Facilitators | |

| Macro | General government support [76]. |

| The regulation and enforcement of core labour standards at the national level [75]. | |

| Collaboration between government, governmental ministries, employers and workers organizations, NGOs [77], collaboration between government, economic sectors, and the ILO [72], collaboration with unions [70]. | |

| Inclusion of informal economy workplaces in the national occupational health and safety agenda [77]. | |

| Meso | The adoption of a safety culture by organizations [71]. |

| Public disclosure of monitoring results and public pressure by consumers and investors to improve employment and working conditions [74]. | |

| Efforts to support implementation of initiatives [72,77], such as detailed planning to facilitate enrolment, data collection, and built-in evaluation processes [72] as well as follow-up visits [77]. | |

| Involvement of local stakeholders [71]. | |

| Learning from and building on successful strategies already tested locally (by other employers and workers) [71,77]. | |

| Participative approaches involving all workers [71,77]. | |

| Existing preoccupation of employers with improving employment and working conditions even before the implementation of related initiatives [67]. | |

| Involving competent and independent professionals in occupational health and safety initiatives [69]. | |

| The use of human networks to reach informal workers who are typically not easily accessed by government organizations because of their informality [77]. | |

| The use of existing networks of worker cooperatives, the offering of complementary non-health benefits, and the contracting of high-quality health services and professionals [73] and the subsidizing of the participation premium fees by the government [76] can increase the viability, quick expansion, and success of large insurance schemes. |

| Study Author(s) Year of Publication | Screening Questions | 1. Qualitative Studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1. Are there clear research questions? | S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | |

| Davies, R., 2000 [67] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Manothum, A. et al., 2010 [71] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kawakami, T. et al., 2011 [77] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Can’t tell |

| Bowman, J.R et al., 2014 [70] | No | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | No | No | No |

| Orchiston, A., 2016 [75] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell |

| Screening Questions | 2. Randomized Controlled Trials | ||||||

| S1. Are there clear research questions? | S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | 2.1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | 2.2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | 2.3. Are there complete outcome data? | 2.4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | 2.5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | |

| Vermeulen, S.J. et al., 2011 [69] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Screening Questions | 3. Non-Randomized Studies | ||||||

| S1. Are there clear research questions? | S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? | 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? | 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | |

| Khan, J.A.M. et al., 2020 [73] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Screening Questions | 4. Quantitative Descriptive Studies | ||||||

| S1. Are there clear research questions? | S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | |

| Salvatori, A., 2010 [68] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Can’t tell | No |

| Brown, D. et al., 2014 [74] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Can’t tell | No |

| Si, W., 2021 [76] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | No | Yes |

| Screening Questions | 5. Mixed Methods Studies | ||||||

| S1. Are there clear research questions? | S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | |

| Rothboeck, S. et al., 2018 [72] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gunn, V.; Kreshpaj, B.; Matilla-Santander, N.; Vignola, E.F.; Wegman, D.H.; Hogstedt, C.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Bodin, T.; Orellana, C.; Baron, S.; et al. Initiatives Addressing Precarious Employment and Its Effects on Workers’ Health and Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042232

Gunn V, Kreshpaj B, Matilla-Santander N, Vignola EF, Wegman DH, Hogstedt C, Ahonen EQ, Bodin T, Orellana C, Baron S, et al. Initiatives Addressing Precarious Employment and Its Effects on Workers’ Health and Well-Being: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042232

Chicago/Turabian StyleGunn, Virginia, Bertina Kreshpaj, Nuria Matilla-Santander, Emilia F. Vignola, David H. Wegman, Christer Hogstedt, Emily Q. Ahonen, Theo Bodin, Cecilia Orellana, Sherry Baron, and et al. 2022. "Initiatives Addressing Precarious Employment and Its Effects on Workers’ Health and Well-Being: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042232

APA StyleGunn, V., Kreshpaj, B., Matilla-Santander, N., Vignola, E. F., Wegman, D. H., Hogstedt, C., Ahonen, E. Q., Bodin, T., Orellana, C., Baron, S., Muntaner, C., O’Campo, P., Albin, M., & Håkansta, C. (2022). Initiatives Addressing Precarious Employment and Its Effects on Workers’ Health and Well-Being: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042232