Active Health Governance—A Conceptual Framework Based on a Narrative Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Major Themes in Literature

3.1. Patient-Centered Care (PCC) and Patient Activation (PA)

3.2. Integrated Care (IC) and Community-based Care (CBC)

3.3. Social Determinants of Health (SDH)

3.4. Lifestyle Determinants of Health (LDH)

3.5. Lifespan/Life-Course Health

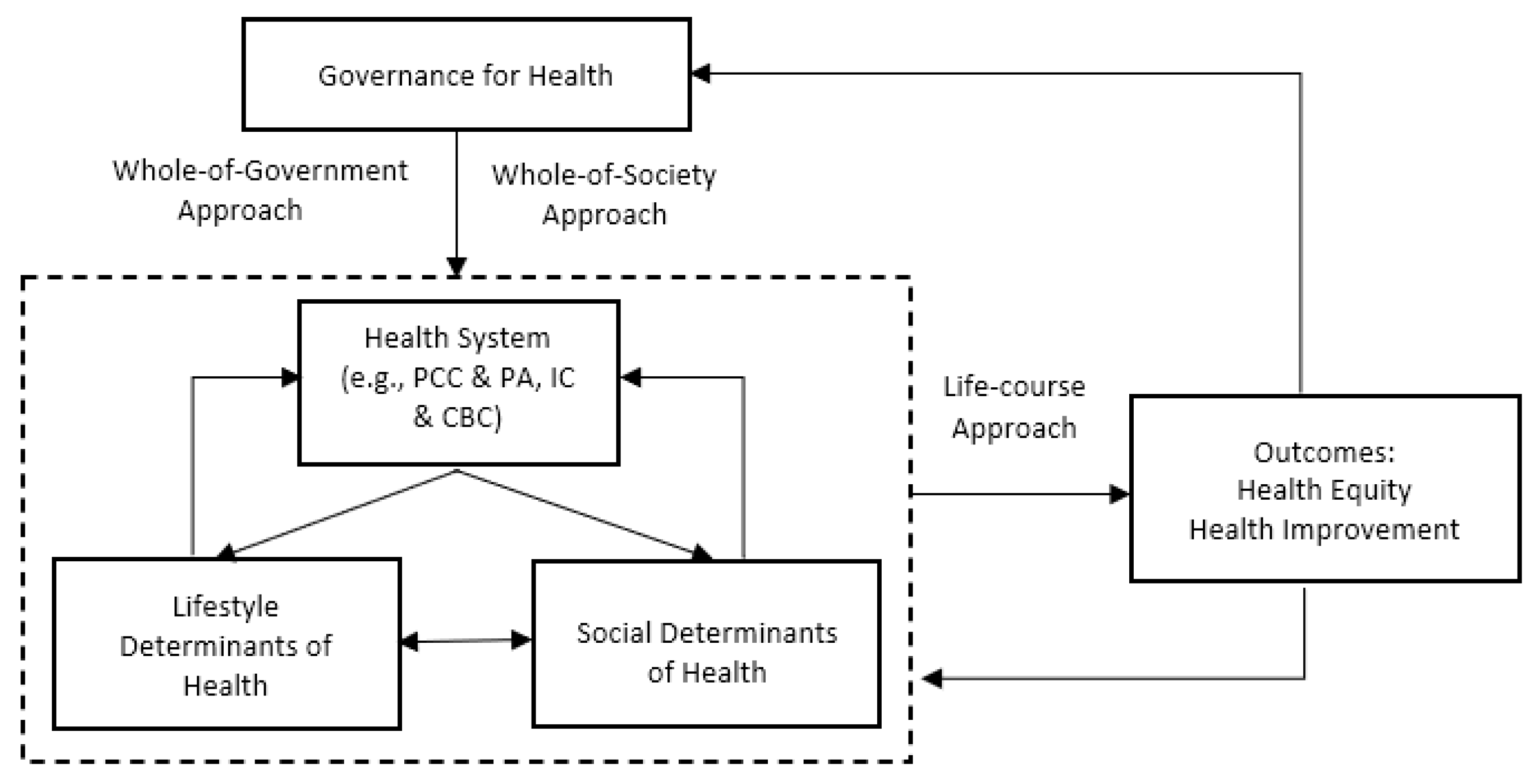

4. A Proposed Framework on Active Health Governance

4.1. Elements of Active Health Governance and Their Interplays

4.2. Characteristics of the Proposed Framework on Active Health Governance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dixon, A.; Poteliakhoff, E. Back to the future: 10 years of European health reforms. Health Econ. Policy Law 2012, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scambler, G. Health inequalities. Sociol. Health Illn. 2012, 34, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elissen, A.; Nolte, E.; Knai, C.; Brunn, M.; Chevreul, K.; Conklin, A.; Durand-Zaleski, I.; Erler, A.; Flamm, M.; Frølich, A.; et al. Is Europe putting theory into practice? A qualitative study of the level of self-management support in chronic care management approaches. BMC Health Res. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nolte, E.; Knai, C.; Saltman, R.B. Assessing Chronic Disease Management in European Health Systems. Concepts and Approaches; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, E.; Lie, M. Policies to Tackle Health Inequalities in Norway: From Laggard to Pioneer? Int. J. Health Serv. 2009, 39, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, S.H.; Braveman, P. Where Health Disparities Begin: The Role of Social And Economic Determinants—And Why Current Policies May Make Matters Worse. Health Aff. 2011, 30, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wolfe, I.; Thompson, M.; Gill, P.; Tamburlini, G.; Blair, M.; Bruel, A.V.D.; Ehrich, J.; Mantovani, M.P.; Janson, S.; Karanikolos, M.; et al. Health services for children in western Europe. Lancet 2013, 381, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechel, B.; Grundy, E.; Robine, J.-M.; Cylus, J.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Knai, C.; McKee, M. Ageing in the European Union. Lancet 2013, 381, 1312–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechel, B.; Mladovsky, P.; Ingleby, D.; Mackenbach, J.P.; McKee, M. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet 2013, 381, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Policies and Practices for Mental Health in Europe: Meeting the Challenges; WHO Reginal Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Karanikolos, M.; McKee, M. The unequal health of Europeans: Successes and failures of policies. Lancet 2013, 381, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.; Mackenbach, J. Successes and Failures of Health Policy in Europe: Four Decades of Divergent Trends and Converging Challenges; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, V. What is a national health policy? Int. J. Health Serv. 2007, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Raftery, J.; Hanney, S.; Glover, M. Research impact: A narrative review. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lloyd, C. The stigmatization of problem drug users: A narrative literature review. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2013, 20, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, P.; Gilbody, S. Stepped care in psychological therapies: Access, effectiveness and efficiency: Narrative literature review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 186, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Watters, A.L.; Epstein, J.B.; Agulnik, M. Oral complications of targeted cancer therapies: A narrative literature review. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shachak, A.; Reis, S. The impact of electronic medical records on patient-doctor communication during consultation: A narrative literature review. J. Evaluation Clin. Pr. 2009, 15, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, N.; Morgan, K.; Conry, M.C.; McGowan, Y.; Montgomery, A.; McGee, H. Quality of care and health professional burnout: Narrative literature review. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2014, 27, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Epstein, R.M.; Fiscella, K.; Lesser, C.S.; Stange, K.C. Why The Nation Needs a Policy Push on Patient-Centered Health Care. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.J.; Burgers, J.; Friedberg, M.; Rosenthal, M.B.; Leape, L.; Schneider, E. Defining and measuring integrated patient care: Pro-moting the next frontier in health care delivery. Med Care Res. Rev. 2011, 68, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Issac, T.; Zaslavsky, M.; Cleary, P.D.; Landon, B.E. The relationship between patients’ perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 45, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Epstein, R.M.; Street, R.L. The Values and Value of Patient-Centered Care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2011, 9, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Greene, J.; Overton, V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; Delivery systems should know their patients’ scores’. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activatiuon in patients and consumers. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fumagalli, L.P.; Radaelli, G.; Lettieri, E.; Bertele’, P.; Masella, C. Patient Empowerment and its neighbours: Clarifying the boundaries and their mutual relationships. Health Policy 2015, 119, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosen, D.M.; Schmittdiel, J.; Hibbard, J.H.; Sobel, D.; Remmers, C.; Bellows, J. Is Patient Activation Associated With Outcomes of Care for Adults With Chronic Conditions? J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2007, 30, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greene, J.; Hibbard, J.H.; Sacks, R.; Overton, V.; Parrotta, C.D. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Integrated Care Models: An Overview; WHO Reginal Office for Europe Working Document: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- What is Integrated Care? An overview of Integrated Care in NHS; Nuffield Trust Research Report 2011. Available online: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/what-is-integrated-care (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Nolte, E.; Knai, C.; Hofmarcher, M.; Conklin, A.; Erler, A.; Elissen, A.; Flamm, M.; Fullerton, B.; Sönnichsen, A.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M. Overcoming fragmentation in health care: Chronic care in Austria, Germany and the Netherlands. Health Econ. Policy Law 2012, 7, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Busse, R.; Blumel, M.; Scheller-Kreinsen, D.; Zentner, A. Tackling chronic disease in Europe: Strategies, interventions and challenges. Eur. Obs. Health Syst. Policies 2010, 20, 9–89. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, V.; Moreira, J.P. Approaches to developing integrated care in Europe: A systematic literature review. J. Manag. Mark. Healthcare 2011, 4, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmarcher, M.M.; Oxley, H.; Rusticelli, E. Improved Health System Performance through better Care Coordination; OECD: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Veeman, I.; Raak, A.; Paulus, A. Comparing integrated care policy in Europe: Does policy matter? Health Policy 2008, 85, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exworthy, M.; Powell, M.; Glasby, J. The governance of integrated health and social care in England since 2010: Great expectations not met once again? Health Policy 2017, 121, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham, A.; Morton-Chang, F.; Williams, A.P.; Miller, F.A. Rebalancing health systems toward community-based care: The role of subsectoral politics. Health Policy 2018, 122, 1260–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, L.; Schäfer, W.; Pavlic, D.R.; Groenewegen, P. Community orientation of general practitioners in 34 countries. Health Policy 2018, 122, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Re-Ports 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Review of Social Determinants and the Health Divide in the WHO European Region: Final Report; WHO Reginal Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. CSDH Final Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Bell, R.; Bloomer, E.; Goldblatt, P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012, 380, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, R.L.J.; Glover, C.M.; Cené, C.W.; Glik, D.C.; Henderson, J.A.; Williams, D.R. Evaluating Strategies for Reducing Health Disparities by Addressing the Social Determinants Of Health. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fraze, T.; Lewis, V.A.; Rodriguez, H.; Fisher, E.S. Housing, Transportation, And Food: How ACOs Seek to Improve Population Health by Addressing Nonmedical Needs of Patients. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puig-Barrachina, V.; Malmusi, D.; Martínez, J.M.; Benach, J. Monitoring Social Determinants of Health Inequalities: The Impact of Unemployment among Vulnerable Groups. Int. J. Heal. Serv. 2011, 41, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health: Levelling up Part 2; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K. Racism and health: Antiracism is an important health issue. BMJ 2003, 32, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Came, H. Sites of institutional racism in public health policy making in New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 106, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paradies, Y.; Ben, J.; Denson, N.; Elias, A.; Priest, N.; Pieterse, A.; Gupta, A.; Kelaher, M.; Gee, G. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boyd, R.W.; Lindo, E.G.; Weeks, L.D.; McLemore, M.R. On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Aff. Blog 2020, 10, 10.1377. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.K.; Sherriff, N. The gradient in health inequalities among families and children: A review of evaluation frameworks. Health Policy 2011, 101, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Crosing Sectors–Experiences in Intersectoral Action, Public Policy and Health; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Cananda, 2007.

- Marmot, M.; Friel, S.; Bell, R. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008, 372, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Healthy Living: What is a Healthy Lifestyle? World Health Organization Reginal Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, M. Lifestyle determinants of health: Isn’t it all about genetics and environment? Nurs. Outlook 2017, 65, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimwe, K., Viswanath, Eds.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Notara, V.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.E. Secondary Prevention of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Socio-economic and Lifestyle Determinants: A Literature Review. Central Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 22, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baal, P.H.; Brouwer, W.B.; Hoogenveen, R.T.; Feenstra, T.L. Increasing tobacco taxes: A cheap tool to increase public health. Health Policy 2007, 82, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Currie, L.M.; Kabir, Z.; Clancy, L. The efficacy of different models of smoke-free laws in reducing exposure to sec-ond-hand smoke: A multi-country comparison. Health Policy 2013, 110, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.A.; McDaniel, P.A.; Hiilamo, H.; Malone, R.E. Policy coherence, integration, and proportionality in tobacco control: Should tobacco sales be limited to government outlets? J. Public Health Policy 2017, 38, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannocci, A.; Backhaus, I.; D’Egidio, V.; Federici, A.; Villari, P.; Torre, G. What public health strategies work to reduce the tobacco demand among young people? An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Health Policy 2019, 123, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuijpers, T.G.; Willemsen, M.C.; Kunst, A.E. Public support for tobacco control policies: The role of the protection of children against tobacco. Health Policy 2018, 122, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jou, J.; Techakehakij, W. International application of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxation in obesity reduction: Factors that may influence policy effectiveness in country-specific contexts. Health Policy 2012, 107, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, L.P.; McNall, A.D. Alcohol prices, taxes, and alcohol-related harms: A critical review of natural experiments in alcohol policy for nine countries. Health Policy 2016, 120, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbel, B.; Kersh, R.; Brescoll, V.L.; Dixon, L.B. Calorie Labeling and Food Choices: A First Look at The Effects On Low-Income People In New York City. Health Aff. 2009, 28, w1110–w1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jonathan, C.; Alejandro, T.; Courtney, A.; Elbel, B. Five years later: Awareness of New York city’s calorie labels declined, with changes in calories purchased. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Breda, J.; Jakovljevic, J.; Rathmes, G.; Mendes, R.; Fontaine, O.; Hollmann, S.; Rütten, A.; Gelius, P.; Kahlmeier, S.; Galea, G. Promoting health-enhancing physical activity in Europe: Current state of surveillance, policy development and implementation. Health Policy 2018, 122, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, T.; Højgaard, B.; Gyrd-Hansen, D. Physical exercise versus shorter life expectancy? An investigation into preferences for physical activity using a stated preference approach. Health Policy 2019, 123, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeder, L.D.; Scheepers, E.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Schuit, J. Health in All Policies? The case of policies to promote bicycle use in the Netherlands. J. Public Health Policy 2015, 36, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conti, G.; Heckman, J.J. The Developmental Approach to Child and Adult Health; NBER Working Paper No. 18664; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.; Barclay, C. Health Disparities Beginning in Childhood: A Life-Course Perspective. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S163–S175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pratt, B.A.; Frost, L.J. The Life Course Approach to Health: A Rapid Review of the Literature; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jacco, C.; Baird, J.; Barker, M.; Cooper, C.; Hanson, M. The Importance of a Life Course Approach to Health: Chronic Disease Risk from Preconception through Adolescence and Adulthood; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla, S.; Sadana, R.; Montesinos, E.V.; Beard, J.; Vasdeki, J.F.; De Carvalho, I.A. A life-course approach to health: Synergy with sustainable development goals. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kickbusch, I.; Gleicher, D. Governance for Health in the 21st Century: A Study Conducted for the WHO Regional Office for Europe; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health 2020—A European Policy Framework Supporting Action across Government and Society for Health and Well-Being; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lencucha, R.; Drope, J.; Chavez, J.J. Whole-of-government approaches to NCDs: The case of the Philippines Interagency Committee—Tobacco. Health Policy Plan. 2015, 30, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kickbusch, I.; Behrendt, T. Implementing a Health 2020 Vision: Governance for Health in the 21st Century. Making it Happen; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Bakker, M.J.; Kunst, A.E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in Europe: An overview. In Reducing Inequalities in Health: A European Perspective; Machenhach, J.P., Bakker, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stringhini, S.; Sabia, S.; Shipley, M.; Brunner, E.; Nabi, H.; Kivimaki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. J. Am. Med Assoc. 2010, 303, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manderbacka, K.; Peltonen, R.; Lumme, S.; Keskimäki, I.; Tarkiainen, L.; Martikainen, P. The contribution of health policy and care to income differences in life expectancy—A register based cohort study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, N.E.; Ostrove, J.M. Socioeconomic Status and Health: What We Know and What We Don’t. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 896, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000—Health systems: Improving Performance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008—Primary Health Care: Now More than Ever; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, I.; Barasa, E.; Nxumalo, N.; Cleary, S.; Goudge, J.; Molyneux, S.; Tsofa, B.; Lehmann, U. Everyday resilience in district health systems: Emerging insights from the front lines in Kenya and South Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nolte, E.; McKee, M. Does Health Care Save Lives? Avoidable Mortality Revised; The Nuffield Trust: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, J.; Rosskam, E.; Leka, S. Report of Task Group 2: Employment and Working Conditions including Occupation, Unemployment and Migrant Workers; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ran, B. Network governance and collaborative governance: A thematic analysis on their similarities, differences, and entanglements. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, B.; Qi, H. The Entangled Twins: Power and Trust in Collaborative Governance. Adm. Soc. 2019, 51, 607–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, B.; Qi, H. Contingencies of power sharing in collaborative governance. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2018, 48, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingleby, D. Moving upstream: Changing policy scripts on migrant and ethnic minority health. Health Policy 2019, 123, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health: WHO Guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe, N.; Wahl, B. Artificial Intelligence and The Future of Globe Health. Lancet 2020, 395, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Ran, B. Active Health Governance—A Conceptual Framework Based on a Narrative Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042289

Zhang K, Ran B. Active Health Governance—A Conceptual Framework Based on a Narrative Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042289

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Kuili, and Bing Ran. 2022. "Active Health Governance—A Conceptual Framework Based on a Narrative Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042289