1. Introduction

In the past two decades, a total of 7348 natural disasters occurred around the world, resulting in 1.23 million deaths, affecting the jobs, property, and health of about 4 billion people, and causing a loss of

$2.97 trillion to the world economy [

1]. In the face of more frequent and intense natural disasters, all we can do is prevent and respond correctly. In fact, after the disaster, many residential areas still face the threat of disaster. For example, after an earthquake disaster occurs, it will be accompanied by a series of secondary disasters such as collapses, landslides, and mudslides [

2,

3]. However, many residents living in earthquake-threatened areas, even in the face of disasters or secondary disasters, are unwilling to evacuate or relocate [

4,

5,

6]. Why does this phenomenon occur? In this case, it becomes essential to understand how people make decisions when dealing with risks.

Risk-coping behaviors refer to people’s behaviors in response to natural disaster risks. Place attachment is undoubtedly a critical explanatory factor when understanding people’s response to natural disasters [

7,

8]. Place attachment refers to a positive emotional bond between people and a particular place [

9], one of the most important psychological factors in the relationship between people and location [

10]. Although economic and social factors tend to dominate behavior choices, more and more literature shows that place attachment has many psychological benefits [

11,

12], affecting residents’ coping behaviors. Evacuation and relocation are the two most common coping behaviors for people to respond to earthquake shocks. Both of them have been proven to be effective in reducing disaster losses [

13,

14]. Evacuation refers to the emergency transfer of people from a dangerous area to avoid or reduce the impact of a disaster; under normal circumstances, they can return to the original area after a certain period [

15]. Relocation refers to people moving out of dangerous areas to avoid or reduce the long-term impact of disasters. It is difficult to predict the time of their return to the original area, or if they will ever return to their original place of residence [

16]. Although there is a difference in essence between evacuation and relocation, they are both actions away from the risk area, except that one is temporary and the other is permanent. According to the current empirical analysis results, scholars generally believe that residents’ attachment to place will hinder them from staying away from risk areas. For example, Lavigne et al. [

17] studied Indonesians living near volcanoes and found that their attachment to the place explained the failure of the evacuation plan in the form of cultural beliefs. Boon [

18] investigated rural residents’ perceptions in Australia before and after flood disasters. They found that residents are reluctant to relocate even if they have experienced multiple floods; the stronger the flood victims’ attachment to place, the more difficult it is for them to accept relocation. Similarly, in a study on the behavior of Norwegian residents facing the risk of oil spills, a strong sense of place was found to be negatively related to the intention to relocate [

19]. In these studies, place attachment as a barrier affects residents’ response to risk.

In addition to directly affecting residents’ risk response decisions, place attachment is also considered to be related to residents’ perceived risk. On the one hand, some studies have shown that there is a positive connection between place attachment and risk perception. For example, Stain et al. [

20] studied people who have suffered from drought for a long time and found that people’s strong sense of place increases their worries about drought. On the other hand, some studies point out that there is a negative connection between place attachment and risk perception [

21,

22]. However, Bernardo [

23] classified Portugal’s different types of risks into different levels, and found that place attachment helps to amplify the perception of high-probability risk (low risk), while weakening the perception of low-probability risk (high risk). Although these findings are contradictory, they reflect that there is indeed a close connection between place attachment and perceived risk. Perceived risk describes how a person assesses his possibility of facing threats [

24], and the perceived efficacy reflects his assessment of his ability to avoid threats [

25]. They are the main concern in the discussion of factors affecting natural disaster response [

26,

27]. Since place attachment is significantly related to perceived risk, is there a connection between place attachment and perceived efficacy? As Relph [

28] asserted, if a person feels that they belong to a place, they will feel safe rather than threatened, closed rather than exposed, and relaxed rather than tense. It stands to reason that the sense of security can derive from the reduction of risk perception or the improvement of efficacy beliefs. However, so far, few studies have systematically analyzed the relationship between place attachment and efficacy beliefs. Twigger-Ross et al. [

29] pointed out that place identity arises when people think that the environment is easier to manage and therefore easier to integrate into their self-conceptualisation. In other words, if the place is integrated into the identity, it means that the place can bring people a sense of particularity, continuity, self-esteem, and self-efficacy [

30]. At the same time, considering the close connection between place attachment and risk coping behavior, we immediately put forward a conjecture: if there is a connection between place attachment and efficacy beliefs, can place attachment affect residents’ risk-coping behavior through efficacy beliefs? Furthermore, is the mechanism of action for the two different risk-coping behaviors of evacuation and relocation the same?

In the existing studies, scholars have carried out a great amount of research on the influence of place attachment on residents’ risk coping behavior. The current study results reveal the crucial role of place attachment in the decision of residents to stay in risk areas, but there are still limitations. It is mainly reflected in the following three aspects: Firstly, from the perspective of the research area, the previous research primarily concentrated on typically developed countries, such as the United States [

31], Norway [

19], Australia [

18], etc., while less attention was paid to developing countries. At the same time, compared with flooded areas [

32,

33], volcano threatened areas [

17,

34], and hurricane threatened areas [

35], existing studies have paid less attention to earthquake threatened areas. As a natural disaster, an earthquake can not only cause various damages itself, but also form a disaster chain and induce various secondary disasters [

36]. The occurrence of these disasters will continue to reconstruct the place attachment of the residents in the disaster-threatening area [

37]. Therefore, more research needs to be conducted on earthquakes. Secondly, from the perspective of research content, although many works of literature have explored the relationship between place attachment and residents’ risk coping behavior, existing research has mainly focused on a particular behavior of residents, such as disaster preparedness [

38], evacuation [

7], and relocation [

39], and lacked simultaneous attention and comparison of two or more risk-coping behaviors. For example, evacuation and relocation are two widespread coping behaviors when people respond to earthquake disasters. However, there is a difference between these two behaviors, with evacuation resulting in a return to the area of origin, whereas relocation usually does not. So, in the same area, would residents with a stronger attachment to the place tend to choose to evacuate rather than relocate? Therefore, it is vital to simultaneously focus on the relationship between place attachment and these two coping behaviors. In addition, existing research primarily discusses the role of perceived risk in place attachment and risk-coping behavior [

40,

41], while there is almost no attention to the efficacy beliefs, another important psychological factor in the decision-making process of residents’ risk coping behavior. Thirdly, from the perspective of research methods, most studies usually use conventional regression analysis (such as Logit/OLS) [

39]. Still, considering the complexity of the interaction between variables, conventional regression results may ignore the hidden relationship between variables. The structural equation model (SEM) provides a conceptual modeling and verification process for the many difficult-to-measure concepts involved in the study and can evaluate multi-dimensional and interrelated relationships [

42,

43]. Therefore, the use of structural equation models can help us better analyze the complex relationship between place attachment and coping behavior.

In this context, this study focuses on the residents in the earthquake-prone areas of Sichuan Province, introduces efficacy beliefs into the study of place attachment and residents’ risk coping behaviors, tries to build a new analysis framework, and verifies it by partial least squares method (PLS-SEM). Our research attempts to understand the complex relationship among place attachment, efficacy beliefs, and two different risk coping behaviors (evacuation and relocation). To this end, this research aims to solve the following problems:

- (1)

What are the characteristics of place attachment, efficacy beliefs, and risk coping behavior of residents in the earthquake-prone areas?

- (2)

What is the mechanism of place attachment and efficacy beliefs in residents’ disaster risk coping behavior in earthquake-prone areas?

The sections in this study are arranged as follows:

Section 2 introduces the literature review;

Section 3 introduces the research model and hypothesis;

Section 4 introduces the method of testing the research model;

Section 5 introduces the research results;

Section 6 introduces the key findings, research contributions, and research limitations.

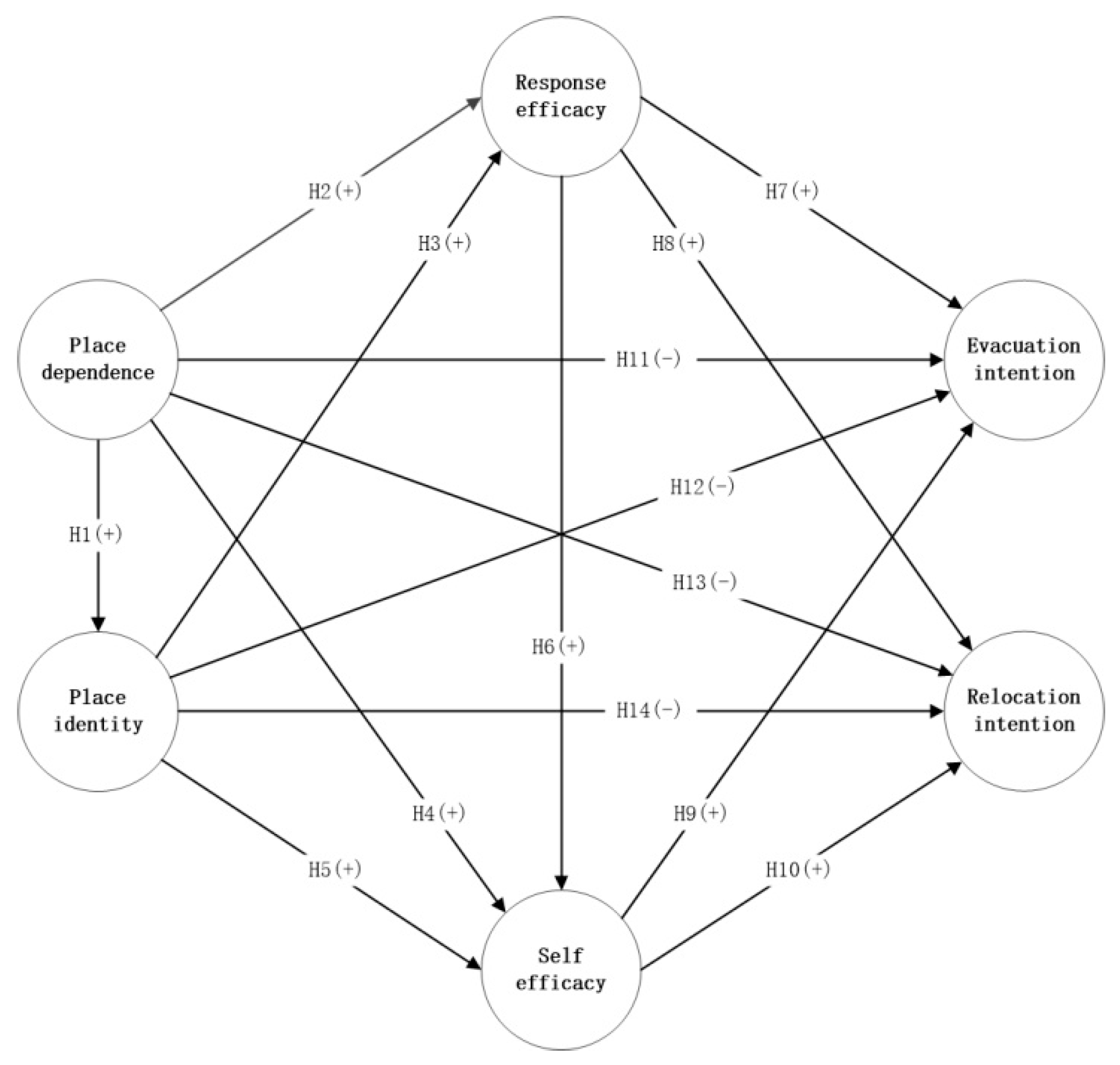

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

Consistent with Williams et al. [

51], our study suggests that people’s attachment to place is based on the following two factors, i.e., PD and PI. In fact, a person may be attached to a place but does not identify with it (for example, a person likes to live in a place and wants to stay there but feels that the place is not part of his identity). Due to PI having a sensory dimension, it takes a long time to experience and feel to produce the sense and symbolic meaning related to the place [

30]. In other words, the degree and duration of PD will further affect PI. Therefore, the research hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). PD has a positive significanteffect on PI.

Research on place attachment and efficacy beliefs is limited in the context of disaster risk management. According to Twigger-Ross et al. [

29] on place and identity processes, place attachment can produce a greater sense of SE because the environment preserves self-perception. Wang et al. [

66] investigated the place attachment and disaster preparedness of residents in Shandong, China. They found that place attachment is highly correlated with SE, and SE plays a mediating role between place attachment and disaster preparedness. Thus, familiarity and attachment to a place may make people feel unique [

67], resulting in positive evaluations of place control and self-competence [

68]. However, few studies have linked place attachment to RE. We believe that the sense of control brought about by high levels of place attachment [

69] makes residents believe that coping measures are effective. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). PD has a positive significant effect on RE.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). PI has a positive significanteffect on RE.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). PD has a positive significant effect on SE.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). PI has a positive significanteffect on SE.

SE refers to a person’s confidence level in their ability to take an actual protective response. In contrast, RE refers to the belief that protective actions are actually effective and can protect themselves or others from risk [

27]. Existing studies often use them as predictors of risk-coping behavior [

58,

70] but rarely explore the relationship between them. It’s easy to imagine that people feel more confident that they can successfully deal with risks by perceiving options for effective coping. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). RE has a positive significanteffect on SE.

Efficacy beliefs include perceived SE and RE [

25], consistent with perceived danger, and both are essential components of psychological factors in risk coping [

55]. The higher the level of efficacy beliefs, the stronger the individual’s confidence in their own coping ability. Newnham et al. [

71] evaluated Hong Kong residents’ SE and evacuation barriers. They found that residents who reported high levels of SE had fewer perceived barriers to evacuation and had more potential to prepare for evacuation. Samaddar et al. [

72] investigated the evacuation willingness of residents in flooded areas of Mumbai and found that individuals with a high SE were more inclined to evacuate. Consistently, Bradley et al. [

73] proposed a model of pro-environmental behavior induced by climate change and found that RE can predict environmental protection behavior in the face of environmental threats. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 7 (H7). RE has a positive significant effect on EI.

Hypothesis 8 (H8). RE has a positive significant effect on RI.

Hypothesis 9 (H9). SE has a positive significant effect on EI.

Hypothesis 10 (H10). SE has a positive significant effect on RI.

Place attachment is considered a positive emotional bond between people and a specific place, characterized by the desire to maintain intimacy with the attachment object [

46]. As Fried [

74] noted, people who are forced to relocate are experiencing a period of mourning, just as people experience when important people die. Unfortunately, when a place is threatened by a disaster, it is often necessary to evacuate/relocate to deal with this risk [

75,

76]. However, people may choose to stay in the threatened area in order to avoid an interruption in their relationship with the place. This is also supported by a lot of research [

8,

22]. In addition, strong place attachment is believed to promote the behavioral adaptation of residents [

57]. At the same time, high attachment to place is often accompanied by optimism bias (shown in people’s belief that bad events are unlikely to happen there or their high confidence that they can overcome difficulties), because it protects their identity and reduces negative emotions such as fear and anxiety [

77,

78]. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 11 (H11). PD has a negative significant effect on EI.

Hypothesis 12 (H12). PI has a negative significant effect on EI.

Hypothesis 13 (H13). PD has a negative significant effect on RI.

Hypothesis 14 (H14). PI has a negative significant effect on RI.

We believe that efficacy beliefs play a mediating role between place attachment and coping behavior based on the above analysis. Therefore, the research hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 15 (H15). PD indirectly affects EI by influencing RE.

Hypothesis 16 (H16). PD indirectly affects EI by influencing SE.

Hypothesis 17 (H17). PD indirectly affects RI by influencing RE.

Hypothesis 18 (H18). PD indirectly affects RI by influencing SE.

Hypothesis 19 (H19). PI indirectly affects EI by influencing RE.

Hypothesis 20 (H20). PI indirectly affects EI by influencing SE.

Hypothesis 21 (H21). PI indirectly affects RI by influencing RE.

Hypothesis 22 (H22). PI indirectly affects RI by influencing SE.

Therefore,

Figure 1 is the conceptual framework of this paper.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The connection between place attachment and risk coping strategy, especially residents’ adaptive behavior when facing disaster threats, is a hot topic in many current studies [

8,

99]. Compared with the existing studies, this study mainly makes the following three contributions: Firstly, combining place attachment theory and PADM, this research builds a theoretical analysis framework for residents’ place attachment, efficacy beliefs, and risk coping behavior, and builds a corresponding indicator system; Secondly, the study also focused on the two risk coping behaviors of evacuation and relocation, compared the differences in the effects of place attachment and efficacy beliefs on EI and RI, and provided evidence to explain the different risk-adaptation behaviors of residents; Thirdly, the study successfully proved the mediating role of RE and explored the relationship among place attachment, efficacy beliefs, and coping behavior of residents in the earthquake-threatened area of Sichuan Province.

This study aims to explore how place attachment and efficacy beliefs can be combined to predict residents’ risk coping behaviors. At the same time, the risk coping behaviors of residents are classified as evacuation and relocation, and further explore the decisive factors that affect residents’ intention to evacuate and relocate. The research results show that, first of all, consistent with the results of Vaske et al. [

88] and Su et al. [

100], there is a close relationship between PD and PI. PD precedes PI, and the emergence of PD can enhance the identity of place. Secondly, place attachment significantly impacted on RE, but it had no significant impact on SE. This is inconsistent with research conducted by Wang et al. [

66] on typhoon and flood-threatened areas. They found that place attachment has a positive and significant effect on SE. This may be because the disaster concerned in this study is earthquake. Compared with typhoon and flood disasters, earthquake disasters are sudden and hugely destructive [

101]. Even though farmers’ familiarity and attachment to the place have produced control over the place, this sense of control still cannot support farmers to make a positive assessment of their own ability to cope with the earthquake. Then, as predicted, RE had a positive and significant effect on SE. Moreover, PD had a significant negative impact on RI but no significant impact on EI. Consistent with the thinking of Ariccio et al. [

7], this may be because there is a close connection between the home and the evacuation site (usually only a few minutes to walk). People may think that there is continuity between the home and the evacuation site instead of opposition; therefore, leaving home to the place of evacuation does not pose a threat to place attachment. Nevertheless, relocation means moving away from the place of residence to another place, which obviously affects the place attachment, so it presents this result. In addition, the study also discovered the mediating role of RE. That is, PI can indirectly affect evacuation and relocation intentions by affecting the RE. We believe that RE is one of the most important cognitive variables that connect people’s understanding of risk and their intention to take action. Although the action intention does not necessarily lead to the actual response behavior [

27], it is crucial that the action intention is first formed during the entire disaster response process [

60]. Finally, consistent with relevant research results [

58,

65,

102], efficacy beliefs positively and significantly affected EI and RI. This shows that RE and SE, as significant predictors, have a relatively large explanation for people’s adaptive behavior intention when responding to earthquake disasters. This further confirms the accuracy of the PADM.

In recent years, the Chinese government has gradually developed strong national-disaster preparedness and disaster relief capabilities, including a strong monitoring system [

103,

104,

105], which can detect the occurrence of natural disasters in time and quickly dispatch emergency relief supplies to disaster-stricken areas [

106,

107,

108,

109]. However, despite the strong disaster preparedness and relief capabilities at the national level, the provincial or county level, especially in poor rural areas, is relatively weak in resisting disaster risks. In this case, this study provides some enlightenment for developing an emergency response in poor rural areas. For example, this research found that the strong PD of farmers is one of the reasons that hinders them from taking correct and effective response measures, especially in their acceptance of relocation. This finding affirms the importance of studying man-land relationships and helps policymakers better understand and intervene in people’s behavior in response to disaster threats. On the one hand, we need to continue to step up advocacy campaigns to popularize the effectiveness of disaster prevention measures, encourage residents to protect themselves in emergencies, and pass on the knowledge of disaster reduction to families and communities [

110,

111,

112]. On the other hand, it is necessary to consider the residents’ special feelings towards the place and fully respect the relationship between people and place. For example, for residents with strong local attachment and low willingness to relocate, policies should be formulated to guide them to make perfect disaster preparedness instead of forced relocation.

This study still has some shortcomings, which can be further explored in future research. For example, residents have different perceptions of the effectiveness of evacuation and relocation. However, the measurement of RE in this article only includes three questions about evacuation, and the RE variable constructed in this way may not be objective and accurate. Additionally, this study only uses cross-sectional data to explore the relationship between residents’ place attachment and their risk coping behaviors. At the same time, their place attachment (such as PI and PD) may change dynamically [

48,

113], and panel data is needed to reveal better the impact of place attachment on residents’ evacuation and relocation behaviors. In addition, it may be useful to explore the possible relationship between age and place attachment as much of the sample was older. It is reasonable that elders with a longer-standing connection to the land may have unique levels of place attachment compared with others. Finally, although this study uses quantitative analysis methods to reveal the mechanism of place attachment and efficacy beliefs on residents’ risk-coping behaviors, it cannot automatically obtain a reasonable explanation for the phenomenon that people still stay in disaster risk areas in reality. For example, some social conditions such as class, SES, or wealth/resources also play an important role in coping behavior. Practical obstacles (such as lack of time, money, knowledge, or social support) due to these factors may affect efficacy, evacuation, or relocation. Therefore, qualitative methods can be introduced in the next study to make the interpretation of the results more convincing.