Strengths and Weaknesses of the Pharmacovigilance Systems in Three Arab Countries: A Mixed-Methods Study Using the WHO Pharmacovigilance Indicators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Data Collection, Sampling, and Recruitment

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

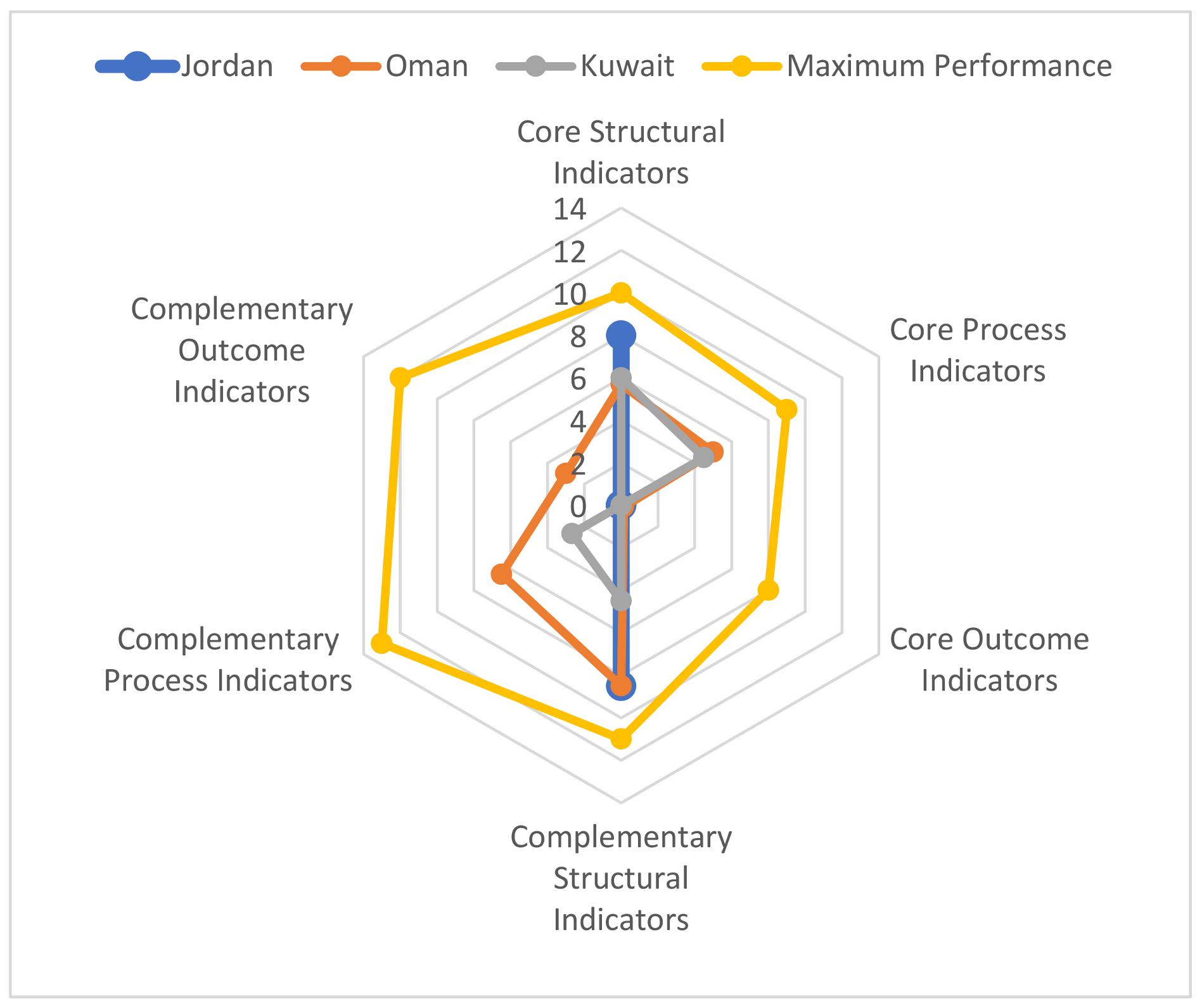

3. Results

3.1. Core Indicators

3.1.1. Core Structural Indicators

“This [the establishment of an official PV department as a strength] is because it was a section of a department before, therefore was not that much importance placed on the section in terms of the reports received and increasing their numbers.”(Participant 1, NPVC, Oman)

“The lack of a dedicated PV department is a weakness… the dedicated department is very important to act on a legal basis with proper staff, with proper infrastructure, with proper independent decisions, to have the full structure, full capacity to work with a proper PV system.”(Participant 17, NPVC, Kuwait)

“Being part of the regulatory body is good for PV in that you have the tools, you have the law, you can go see patient files, do further investigations within the hospitals. That’s why I think it’s our strength to be part of the regulatory body.”(Participant 7, NPVC, Jordan)

“…we feel tied up with the fact that we haven’t got a legal framework, so that’s a big weakness… the activities are being carried out, but the activities are being carried out with no umbrella, there’s nothing that protects them.”(Participant 11, NPVC, Kuwait)

“The fact that the drug authority and the PV centre are separate from the MOH is, in my opinion, a strength. ... A drug authority, which is an entity that gives and takes back the marketing authorisation, are controlling the industry through this, so if you don’t report, and you don’t have a system, and you are not compliant with regulations, we have the authority to withdraw your marketing licence. The MOH does not have this authority.”(Participant 14, PI, Jordan)

“…we don’t have a budget for things like printing materials, conducting training outside. When you perform training outside you need coverage to sponsor the event, to provide meals for those attending. We don’t have a budget here at the Jordan Food and Drug Administration (JFDA) for our department for these activities. So, you need sponsors from outside to implement these things.”(Participant 2, NPVC, Jordan)

“It’s [the lack of staff] affecting our work in that we have many PV activities to do, for example, we have to enter reports onto the VigiFlow, which should be done regularly, but is not. So, once we have time then we are entering our reports into VigiFlow. So, this is affecting our implementation, for example, we should by now have completed the inspection on all companies and all drug stores, but we have not. There is also training and awareness campaigns, which is not being done according to the scheduled program.”(Participant 2, NPVC, Jordan)

“This [staff shortage] is the major factor, because for example when you want to study a PSUR you need teamwork to be able to do this quickly. The files for the PSUR are large. One person cannot review every file for every medicine. Also, we are receiving PSURs every six months for every medicine.”(Participant 1, NPVC, Oman)

“…the turnover of staff between the departments also, it is a weakness that we spend time and money to do training for [a] certain individual and then he will go to another department.”(Participant 7, NPVC, Jordan)

“…in other countries, HCPs’ awareness is very high. It is part of their education in the universities. Here, it’s not implemented yet, so the HCPs, they are shaky, shall we inform or not? How to report? When to report? What to report? Still, their awareness and the level of education… [has] not reached the level of other people [in other countries], so it’s still not high. The awareness level is not high.”(Participant 13, PI, Kuwait)

“Another positive is the presence of the Health Hazard Committee, which has benefitted us a lot since it is composed of individuals representing different sectors and from different healthcare professions.”(Participant 6, NPVC, Jordan)

“…I always think that we [the NPVC] are sitting in a remote position and we are not in the practising side… we are not able to find out whether it is the prejudice among the healthcare professionals or the patients that they say it is ineffectiveness, or whether it is actual ineffectiveness which is happening.”(Participant 5, NPVC, Oman)

3.1.2. Core Process Indicators

“Although HCPs may encounter patients with ADRs, some of them don’t know that [they have encountered an ADR], or some of them don’t know that they have to report it, or that it’s important to report it. So, I think that one weakness is that not all HCPs report ADRs.”(Participant 3, peripheral PV centre, Jordan)

“Even though we have 1000 reports, I believe that 70–80% of them are of poor quality. And personally, I know that in one year I provided the PV centre with more than 160 reports, and I later found out that only 40 of them were very useful. …But unfortunately, we never worked on the reports in terms of their quality, we never did statistics on the reports, we don’t know what the gap is, what is the problem with our reports, why are our reports not of good quality.”(Participant 4, regional PV centre, Jordan)

3.1.3. Core Outcome Indicators

“One of the reasons [for the deficiency in signal detection] is that we don’t have enough data, quality data, and the people at the PV centre they focus on collecting the reports without taking it for a further step of analysis and investigation. I think this as well is an issue that our industry has because it is not only the duty of the healthcare system or the health authorities, but also one of the responsibilities of the MAH.”(Participant 4, regional PV centre, Jordan)

“…we need more reporting to have our own decision-making process based on our own data in Kuwait. We don’t want to depend on international data. We need to depend on our own data to take into consideration our lifestyle, our raised diet, concurrent medications, morbidity and so on, so that’s why this [i.e., under-reporting] is one of the weaknesses and one of the barriers that we need to overcome.”(Participant 17, NPVC, Kuwait)

3.2. Complementary Indicators

3.2.1. Complementary Structural Indicators

“…the IT system [is a weakness], it’s very important for our work to get a proper database and to have a system such as the VigiFlow or the VigiLyze and VigiBase to help get a broader vision of the different cases worldwide. For signal detection, it’s very important to have a system as well, to help get the proper signal as quickly as possible and as efficiently as possible.”(Participant 17, NPVC, Kuwait)

3.2.2. Complementary Process Indicators

“A point of strength is that there is now awareness. I feel the first step that we took was to increase awareness of HCPs and the general public. This resulted in us receiving many reports.”(Participant 10, NPVC, Oman)

“...the awareness campaigns are still not strong enough. We don’t hear in Kuwait, I didn’t hear that there is a committee for PV or an awareness campaign, to increase awareness of the patients.”(Participant 13, PI, Kuwait)

3.2.3. Complementary Outcome Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Organisation and Infrastructure

4.2. Policy and Resources

4.3. ADR Reporting Rates and Signal Detection

4.4. Stakeholders’ Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitudes towards PV

4.5. Study Limitation

5. Conclusions

- Lobbying national governments and political parties on the importance of having a functional national PV system to obtain their commitment to supporting the system with legislation as well as suitable and sustained resources.

- Ensuring the establishment of key organisational and infrastructure elements including a dedicated and officially recognised NPVC, an expert advisory committee, and a computerised national database.

- Establishing training and development programmes addressing the key elements of PV and developing guidelines to support best PV practices among HCPs.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Importance of Pharmacovigilance: Safety Monitoring of Medicinal Products. Available online: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s4893e/s4893e.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Rawlins, M.D. Pharmacovigilance: Paradise Lost, Regained or Postponed? The William Withering Lecture 1994. J. R. Coll. Physicians Lond. 1995, 29, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olsson, S.; Pal, S.N.; Dodoo, A. Pharmacovigilance in resource-limited countries. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 8, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garashi, H.Y.; Steinke, D.T.; Schafheutle, E.I. A systematic review of pharmacovigilance systems in developing countries using the WHO pharmacovigilance indicators. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2021. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Qato, D.M. Current state of pharmacovigilance in the Arab and Eastern Mediterranean region: Results of a 2015 survey. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 26, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, T.M.; Mendi, N.; Alenzi, K.A.; Alsowaida, Y. Pharmacovigilance Systems in Arab Countries: Overview of 22 Arab Countries. Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, T.M.; Alenzi, K.A.; Ata, S.I. National pharmacovigilance programs in Arab countries: A quantitative assessment study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2020, 29, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.R. Pharmacovigilance bolstered in the Arab world. Lancet 2014, 384, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bham, B. The first eastern Mediterranean region/Arab countries meeting of pharmacovigilance. Drugs-Real World Outcomes 2015, 2, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilbur, K. Pharmacovigilance in the Middle East: A Survey of 13 Arabic-Speaking Countries. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkland, T.A. Elements of the policymaking system. In An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts, and Models of Policy Making, 4th ed.; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 27–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cacace, M.; Ettelt, S.; Mays, N.; Nolte, E. Assessing quality in cross-country comparisons of health systems and policies: Towards a set of generic quality criteria. Health Policy 2013, 112, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Bank. Surface Area (sq. km)—Jordan, Oman, Kuwait. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.SRF.TOTL.K2?locations=JO-OM-KW (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- World Bank. Population, Total—Jordan, Oman, Kuwait. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?end=2020&locations=JO-OM-KW&start=2020 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Pharmacovigilance Indicators: A Practical Manual for the Assessment of Pharmacovigilance Systems. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186642 (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems (SPS) Program. Indicator-Based Pharmacovigilance Assessment Tool: Manual for Conducting Assessments in Developing Countries. Submitted to the U.S. Agency for International Development by the SPS Program. Available online: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADS167.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Thomson, S.B. Framework Analysis: A Qualitative Methodology for Applied Policy Research. JOAAG 2009, 4, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ampadu, H.H.; Hoekman, J.; Arhinful, D.; Amoama-Dapaah, M.; Leufkens, H.G.M.; Dodoo, A.N.O. Organizational capacities of national pharmacovigilance centres in Africa: Assessment of resource elements associated with successful and unsuccessful pharmacovigilance experiences. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maigetter, K.; Pollock, A.M.; Kadam, A.; Ward, K.; Weiss, M.G. Pharmacovigilance in India, Uganda and South Africa with reference to WHO’s minimum requirements. Int. J. Health Policy Manag.-IJHPM 2015, 4, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isah, A.O.; Pal, S.N.; Olsson, S.; Dodoo, A.; Bencheikh, R.S. Specific features of medicines safety and pharmacovigilance in Africa. Adv. Drug Saf. 2012, 3, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Biswas, P. Pharmacovigilance in Asia. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, S7–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Wong, L.Y.L.; He, Y.; Wong, I.C.K. Pharmacovigilance in China: Current Situation, Successes and Challenges. Drug Saf. 2014, 37, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharf, A.; Alqahtani, N.; Saeed, G.; Alshahrani, A.; Alshahrani, M.; Aljasser, N.; Alquwaizani, M.; Bawazir, S. Saudi Vigilance Program: Challenges and lessons learned. Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ Off. Publ. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2018, 26, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwankesawong, W.; Dhippayom, T.; Tan-Koi, W.-C.; Kongkaew, C. Pharmacovigilance activities in ASEAN countries. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2016, 25, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Logistics Involved in the Organization of the PV Centre. Available online: https://whopvresources.org/center.php (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Olsson, S.; Pal, S.N.; Stergachis, A.; Couper, M.; Olsson, S.; Pal, S.N.; Stergachis, A.; Couper, M. Pharmacovigilance activities in 55 low- and middle-income countries: A questionnaire-based analysis. Drug Saf. 2010, 33, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, C.; Lopez-Gonzalez, E.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Figueiras, A. Strategies to improve adverse drug reaction reporting: A critical and systematic review. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, C.; Varallo, F.; Mastroianni, P. Impact of educational interventions on adverse drug events reporting. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2013, 29, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Colaceci, S.; Giusti, A.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R. Factors that condition the spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions among nurses: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, P.; Brown, D.; Howard, J.; Randall, C. Pharmacists in pharmacovigilance: Can increased diagnostic opportunity in community settings translate to better vigilance? Drug Saf. 2014, 37, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gonzalez, E.; Herdeiro, M.T.; Figueiras, A. Determinants of under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009, 32, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, M.A.; Gelal, A.; Demiral, Y.; Tuncok, Y. Short and long-term impact of pharmacovigilance training on the pharmacovigilance knowledge of medical students. Indian J. Pharm. 2015, 47, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tripathi, R.K.; Jalgaonkar, S.V.; Sarkate, P.V.; Rege, N.N. Implementation of a module to promote competency in adverse drug reaction reporting in undergraduate medical students. Indian J. Pharm. 2016, 48, S69–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reumerman, M.; Tichelaar, J.; Piersma, B.; Richir, M.C.; van Agtmael, M.A. Urgent need to modernize pharmacovigilance education in healthcare curricula: Review of the literature. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 74, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Palaian, S.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Mishra, P.; Shankar, P.R. Impact assessment of pharmacovigilance-related educational intervention on nursing students’ knowledge, attitude and practice: A pre-post study. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2019, 9, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Indicator Item | Assessment | Jordan | Oman | Kuwait |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CST1 | Existence of a pharmacovigilance centre, department, or unit with a standard accommodation | Rational Drug Use and Pharmacovigilance Department | Department of Pharmacovigilance and Drug Information | Quality Assurance Unit—not officially recognised |

| CST2 | Existence of a statutory provision (national policy, legislation) for pharmacovigilance | Law titled “The Pharmacovigilance Directives” | Only “Guideline on GVP in Oman” | Only memos issued to companies |

| CST3 | Existence of a medicines’ regulatory authority or agency | Jordan Food and Drug Administration (JFDA) | Directorate General of Pharmaceutical Affairs and Drug Control (DGPA&DC) | Kuwait Drug and Food Control Administration (KDFCA) |

| CST4 | Existence of any regular financial provision (e.g., statutory budget) for the pharmacovigilance centre | No | No | No |

| CST5 | The pharmacovigilance centre has human resources to carry out its functions properly | 5 full-time employees | 5 full-time employees | 5 full-time and 1 part-time employee |

| CST6 | Existence of a standard ADR reporting form in the setting | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CST6a—Availability of relevant fields in standard ADR reporting form to report medication errors | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| CST6b—Availability of relevant fields in standard ADR reporting form to report suspected counterfeit/substandard medicines | Separate form | Yes | Separate form | |

| CST6c—Availability of relevant fields in standard ADR reporting form to report therapeutic ineffectiveness | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| CST6d—Availability of relevant fields in standard ADR reporting form to report suspected misuse, abuse and/or dependence on medicines | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| CST6e—Availability of a standard ADR reporting form for the general public | Same form as for HCPs | Same form as for HCPs | Same form as for HCPs | |

| CST7 | Existence of a process in place for collection, recording, and analysis of ADR reports | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CST8 | Incorporation of pharmacovigilance into the national curriculum of the various healthcare professions | |||

| CST8a—Medical doctors | No | No | No | |

| CST8b—Dentists | No | No | No | |

| CST8c—Pharmacists | No | Yes | No | |

| CST8d—Nurses or midwives | No | Yes | No | |

| CST8e—Others—to be specified | No | No | No | |

| CST9 | Existence of a newsletter, information bulletin, and/or website as a tool for dissemination of information on pharmacovigilance | Newsletter and website | No | Newsletter |

| CST10 | Existence of a national ADR or pharmacovigilance advisory committee or an expert committee in the setting capable of providing advice on medicine safety | Health Hazard Evaluation Committee | No | No |

| Indicator Item | Assessment | Oman | Kuwait |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP1 | Total number of ADR reports in the previous year (2020) | 1628 | 708 |

| CP1a—Total number of ADR reports received in the previous year (2020) per 100,000 people in the population | 31.88 * | 16.58 * | |

| CP2 | Current total number of reports in the national database | 19,731 | 890 † |

| CP3 | Percentage of total annual reports acknowledged and/or issued feedback | N/A | 100% (acknowledgement) |

| CP4 | Percentage of total reports subjected to causality assessment in the previous year (2020) | N/A | 58.9% |

| CP5 | Percentage of total annual reports satisfactorily completed and submitted to the NPVC in the previous year (2020) | 84.3% | 58.9% |

| CP5a—Of the reports satisfactorily completed and submitted to the NPVC, percentage of reports committed to the WHO database | 84.3% | 0 | |

| CP6 | Percentage of reports of therapeutic ineffectiveness received in the previous year (2020) | 0.80% | N/A |

| CP7 | Percentage of reports on medication errors reported in the previous year (2020) | 4.4% | N/A |

| CP8 | Percentage of registered pharmaceutical companies that have a functional pharmacovigilance system | N/A | N/A |

| CP9 | Number of active surveillance activities that are or were initiated, ongoing, or completed in the past 5 years | 0 | 0 |

| Indicator Item | Assessment | Oman | Kuwait |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO1 | Number of signals detected in the past 5 years by the NPVC | 0 | 0 |

| CO2 | Number of regulatory actions taken in the preceding year (2020) consequent to NPVC activities | 2 * | N/A † |

| CO2a—Product label changes (variation) | - | N/A | |

| CO2b—Safety warnings on medicines | - | N/A | |

| CO2b(i)—To health professionals | - | N/A | |

| CO2b(ii)—To the general public | - | N/A | |

| CO2c—Drug withdrawals | - | N/A | |

| CO2d—Other restrictions on the use of medicines | - | N/A | |

| CO3 | Number of medicine-related hospital admissions per 1000 admissions | N/A | N/A |

| CO4 | Number of medicine-related deaths per 1000 persons served by the hospital per year | N/A | N/A |

| CO5 | Number of medicine-related deaths per 100,000 persons in the population | N/A | N/A |

| CO6 | Average cost (USD) of treatment of medicine-related illness | N/A | N/A |

| CO7 | Average duration (days) of medicine-related extension of hospital stay | N/A | N/A |

| CO8 | Average cost (USD) of medicine-related hospitalisation | N/A | N/A |

| Indicator Item | Assessment | Jordan | Oman | Kuwait |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST1 | Existence of a dedicated computer for pharmacovigilance activities | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ST2 | Existence of a source of data on consumption and prescription of medicines | No | No | No |

| ST3 | Existence of functioning and accessible communication facilities in the NPVC | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ST4 | Existence of a library or other reference source for drug safety information | Yes | Yes | No |

| ST5 | Existence of a computerised case-report management system | VigiFlow | VigiFlow | No |

| ST6 | Existence of a programme (including a laboratory) for monitoring the quality of pharmaceutical products | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ST6a—The programme (including a laboratory) for monitoring the quality of pharmaceutical products collaborates with the pharmacovigilance programme | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| ST7 | Existence of an essential medicines list which is in use | Yes | Yes | No |

| ST8 | Systematic consideration of pharmacovigilance data when developing the main standard treatment guidelines | Yes | Yes | No |

| ST9 | The pharmacovigilance centre organises training courses for: | |||

| ST9a—HCPs | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| ST9b—The general public | No | No | No | |

| ST10 | Availability of web-based pharmacovigilance training tools for: | |||

| ST10a—HCPs | No | No | No | |

| ST10b—The general public | No | No | No | |

| ST11 | Existence of requirements mandating MAHs to submit PSURs | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Indicator Item | Assessment | Oman | Kuwait |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Percentage of healthcare facilities with a functional pharmacovigilance unit (i.e., submitting ≥ 10 reports to the NPVC) in the previous year (2020) | 70% | N/A |

| P2 | Percentage of total reports sent in 2020 by the different stakeholders includes: | ||

| P2a—Medical doctors | 8.9% | N/A | |

| P2b—Dentists | 0 | N/A | |

| P2c—Pharmacists | 81.9% | N/A | |

| P2d—Nurses or midwives | 0 | N/A | |

| P2e—The general public | 0.12% | N/A | |

| P2f—Manufacturers | 8.8% | >95% | |

| P3 | Total number of reports received per million population per year (2020) | 318.80 * | 165.79 * |

| P4 | Average number of reports per number of HCPs per year (2020) includes: | ||

| P4a—Medical doctors | 198 | N/A | |

| P4b—Dentists | 0 | N/A | |

| P4c—Pharmacists | 1474 | N/A | |

| P4d—Nurses or midwives | 0 | N/A | |

| P5 | Percentage of HCPs aware of and knowledgeable about ADRs per facility | N/A | N/A |

| P6 | Percentage of patients leaving a health facility aware of ADRs in general | N/A | N/A |

| P7 | Number of face-to-face training sessions in pharmacovigilance organised in the previous year (2020) for: | ||

| P7a—HCPs | 2 | 0 † | |

| P7b—The general public | 0 | 0 | |

| P8 | Number of individuals who received face-to-face training in pharmacovigilance in the previous year (2020): | ||

| P8a—Health professionals | 55 | 0 | |

| P8b—The general public | 0 | 0 | |

| P9 | Total number of national reports for a specific product per volume of sales of that product in the country (product specific) from the industry | N/A | N/A |

| P10 | Number of registered products with a pharmacovigilance plan and/or a risk management strategy among the MAHs in the country | 105 | N/A |

| P10a—Percentage of registered products with a pharmacovigilance plan and/or a risk management strategy from MAHs in the country | - | N/A | |

| P11 | Percentage of MAHs who submit periodic safety update reports to the regulatory authority as stipulated in the country | 29% | 14% |

| P12 | Number of products voluntarily withdrawn by market authorisation holders because of safety concerns in 2020 | 6 | 7 |

| P12a—Number of summaries of product characteristics (SPCs) updated by market authorisation holders because of safety concerns | - | N/A | |

| P13 | Number of reports from each registered pharmaceutical company received by the NPVC in the previous year (2020) | N/A | N/A |

| Indicator Item | Assessment | Oman | Kuwait |

|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | Percentage of preventable ADRs reported out of the total number of ADRs reported in the preceding year (2020) | 3.54% | N/A |

| O2 | Number of medicine-related congenital malformations per 100,000 births | 1 | N/A |

| O3 | Number of medicines found to be possibly associated with congenital malformations in the past 5 years | 2 | N/A |

| O4 | Percentage of medicines in the pharmaceutical market that are counterfeit/substandard | N/A | N/A |

| O5 | Number of patients affected by a medication error in hospital per 1000 admissions in the previous year (2020) | N/A | N/A |

| O6 | Average work or schooldays lost due to drug-related problems | N/A | N/A |

| O7 | Cost savings (USD) attributed to pharmacovigilance activities | N/A | N/A |

| O8 | Health budget impact (annual and over time) attributed to pharmacovigilance activity | N/A | N/A |

| O9 | Average number of medicines per prescription | N/A | N/A |

| O10 | Percentage of prescriptions with medicines exceeding manufacturer’s recommended dose | N/A | N/A |

| O11 | Percentage of prescription forms prescribing medicines with potential for interaction | N/A | N/A |

| O12 | Percentage of patients receiving information on the use of their medicines and on potential ADRs associated with those medicines | N/A | N/A |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garashi, H.; Steinke, D.; Schafheutle, E. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Pharmacovigilance Systems in Three Arab Countries: A Mixed-Methods Study Using the WHO Pharmacovigilance Indicators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052518

Garashi H, Steinke D, Schafheutle E. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Pharmacovigilance Systems in Three Arab Countries: A Mixed-Methods Study Using the WHO Pharmacovigilance Indicators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052518

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarashi, Hamza, Douglas Steinke, and Ellen Schafheutle. 2022. "Strengths and Weaknesses of the Pharmacovigilance Systems in Three Arab Countries: A Mixed-Methods Study Using the WHO Pharmacovigilance Indicators" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052518

APA StyleGarashi, H., Steinke, D., & Schafheutle, E. (2022). Strengths and Weaknesses of the Pharmacovigilance Systems in Three Arab Countries: A Mixed-Methods Study Using the WHO Pharmacovigilance Indicators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052518