Barriers and Enablers to Food Waste Recycling: A Mixed Methods Study amongst UK Citizens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. General Introduction

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. The UK Food Waste Context

1.2.2. Citizen Behaviour Change

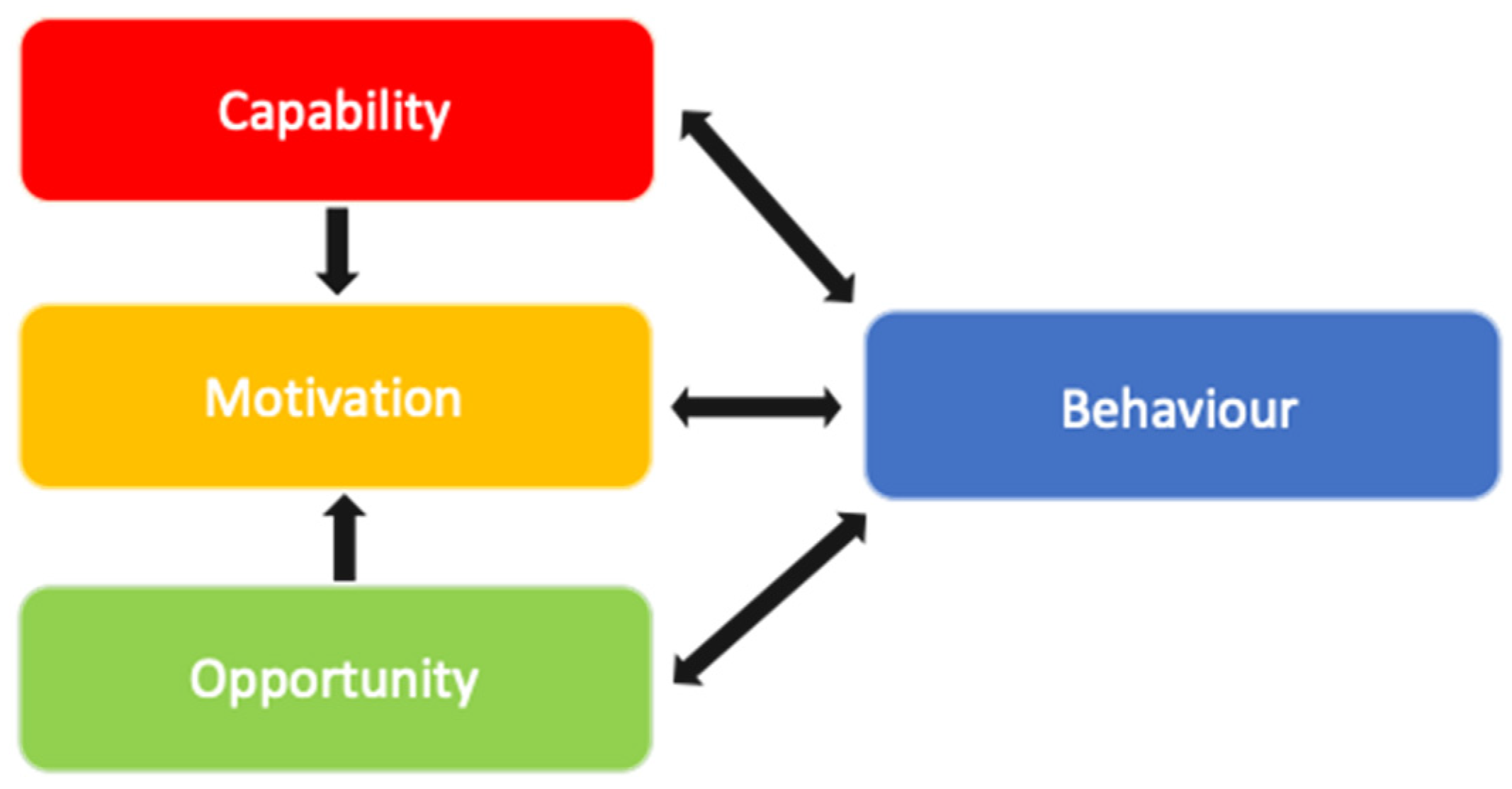

1.2.3. Theoretical Framework

1.3. Study Aims

2. Methods

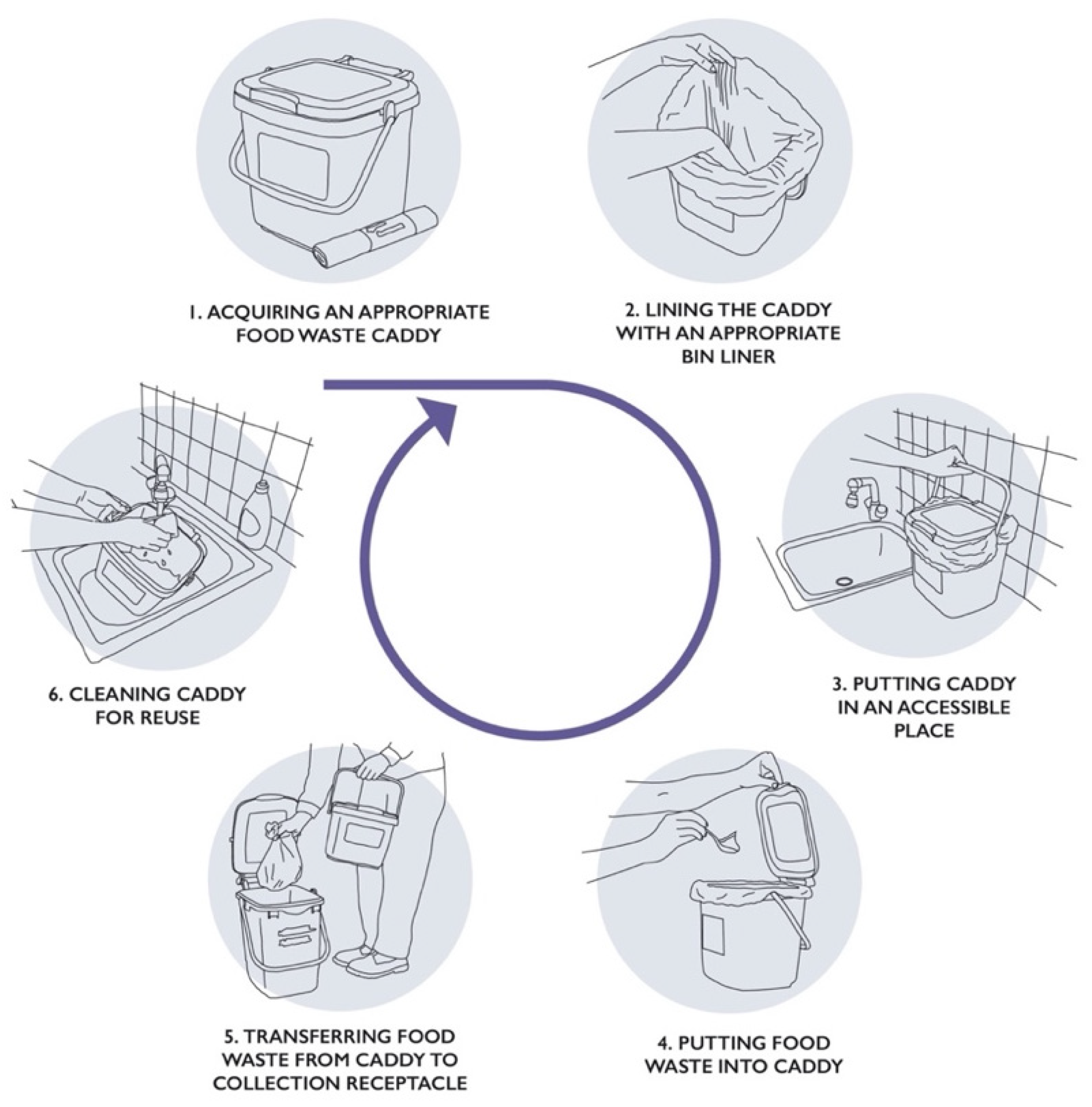

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Procedure

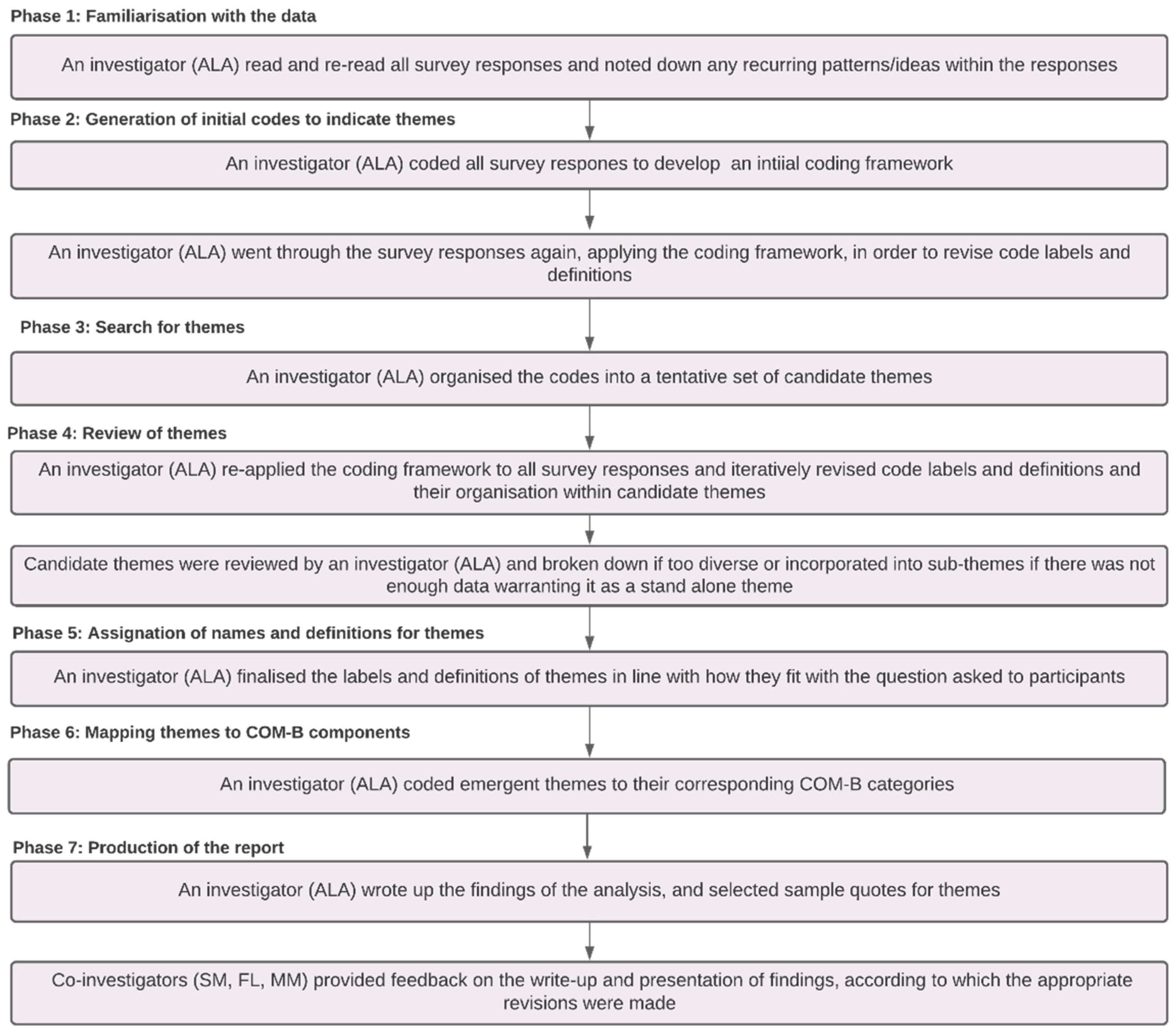

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Factors Associated with Food Waste Recycling

3.2.1. Internal Consistency of Survey

3.2.2. Identification of Covariates

3.2.3. Predicting Food Waste Recycling Behaviour

3.3. Reasons for Not Recycling Food Waste via Council Food Waste Collection

3.4. Reasons for Not Using Compostable Caddy Liners

3.5. Reasons for Not Feeling Ready for Nationwide Food Waste Collection

4. Discussion

Implications, Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| IVC | In Vessel Composting |

| COM-B | Capability–Opportunity–Motivation–Behaviour |

| BCW | Behaviour Change Wheel |

| TDF | Theoretical Domains Framework |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

Appendix A

| TDF Domain | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | An awareness of the existence of something |

| Skills | An ability or proficiency acquired through practice |

| Social/Professional role and identity | A coherent set of behaviours and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Acceptance of the truth, reality or validity about an ability, talent or facility that a person can put to constructive use |

| Optimism | The confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be attained |

| Beliefs about consequences | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about outcomes of behaviour in a given situation |

| Reinforcement | Increasing the probability of a response by arranging a dependent relationship, or contingency, between the response and a given stimulus |

| Intentions | A conscious decision to perform a behaviour or a resolve to act in a certain way |

| Goals | Mental representations of outcomes or end states that an individual wants to achieve |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | The ability to retain information, focus selectively on aspects of the environment and choose between two or more alternatives |

| Environmental context and resources | Any circumstance of a person’s situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence and adaptive behaviour |

| Social influences | Those interpersonal processes that can cause individuals to change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviours |

| Emotion | A complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioural, and physiological elements, by which the individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event |

| Behavioural Regulation | Anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions |

References

- Moult, J.; Allan, S.; Hewitt, C.; Berners-Lee, M. Greenhouse gas emissions of food waste disposal options for UK retailers. Food Policy 2018, 77, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.-H.; Choi, K.-I.; Osako, M.; Dong, J.-I. Evaluation of environmental burdens caused by changes of food waste management systems in Seoul, Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 387, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.H.; Lim, T.Z.; Tan, R.B. Food waste conversion options in Singapore: Environmental impacts based on an LCA perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Matthews, H.S.; Morawski, C. Review and meta-analysis of 82 studies on end-of-life management methods for source separated organics. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance, F.W.R. Analysis of US Food Waste among Food Manufacturers, Retailers, and Restaurants. Available online: https://furtherwithfood.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/FWRA-Food-Waste-Survey-2016-Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Food Recovery Hierarchy. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/food-recovery-hierarchy (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Agovino, M.; Ferrara, M.; Marchesano, K.; Garofalo, A. The separate collection of recyclable waste materials as a flywheel for the circular economy: The role of institutional quality and socio-economic factors. Econ. Politica 2020, 37, 659–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusselaers, J.; Van Der Linden, A. Bio-Waste in Europe—Turning Challenges into Opportunities; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Favoino, E.; Giavini, M. Bio-Waste Generation in the EU: Current Capture Levels and Future Potential; Bio-Based Industries Consortium (BIC): Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WRAP. Food Surplus and Waste in the UK–Key Facts. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021–06/Food%20Surplus%20and%20Waste%20in%20the%20UK%20Key%20Facts%20June%202021.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- DEFRA. Environment Bill. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58–01/0220/200220.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- DEFRA. UK Statistics on Waste; DEFRA: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GOV.WALES. How Wales Became a World Leader in Recycling. Available online: https://gov.wales/how-wales-became-world-leader-recycling#:~:text=99%25%20of%20households%20now%20have,create%20energy%20to%20power%20homes (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Wales Government. Beyond Recycling. Available online: https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-03/beyond-recycling-strategy-document.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- DEFRACommittee. Oral Evidence: Food Waste in England, HC 429; DEFRA: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, S.R.; Bhave, P.P. In-vessel composting of household wastes. Waste Manag. 2006, 26, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.J.; Creamer, K.S. Inhibition of anaerobic digestion process: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4044–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Assessment of Separate Collection Schemes in the 28 Capitals of the EU; European Comission (EC): Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, M.; Soto, M. The efficiency of home composting programmes and compost quality. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEFRA. Rural Population and Migration. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/rural-population-and-migration/rural-population-and-migration (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- British Plastic Federation. Compostable Bags for Organic Waste Collection. Available online: https://www.bpf.co.uk/topics/compostable_bags_for_organic_waste_collection.aspx (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- French, S.D.; Green, S.E.; O’Connor, D.A.; McKenzie, J.E.; Francis, J.J.; Michie, S.; Buchbinder, R.; Schattner, P.; Spike, N.; Grimshaw, J.M. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: A systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel. In A Guide to Designing Interventions, 1st ed.; Silverback Publishing: Sutton, UK, 2014; pp. 1003–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cane, J.; O’Connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- England Public Health. Achieving Behaviour Change: A Guide for Local Government and Partners. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/behaviour-change-guide-for-local-government-and-partners (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Lorencatto, F.; Charani, E.; Sevdalis, N.; Tarrant, C.; Davey, P. Driving sustainable change in antimicrobial prescribing practice: How can social and behavioural sciences help? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2613–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, H.; Krebs, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 1688–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barker, F.; Atkins, L.; de Lusignan, S. Applying the COM-B behaviour model and behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to improve hearing-aid use in adult auditory rehabilitation. Int. J. Audiol. 2016, 55, S90–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szinay, D.; Perski, O.; Jones, A.; Chadborn, T.; Brown, J.; Naughton, F. Perceptions of factors influencing engagement with health and wellbeing apps: A qualitative study using the COM-B model and Theoretical Domains Framework. Qeios 2021, 9, e29098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, L.K.; Saunders, J.M.; Cassell, J.; Curtis, T.; Bastaki, H.; Hartney, T.; Rait, G. Application of the COM-B model to barriers and facilitators to chlamydia testing in general practice for young people and primary care practitioners: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainforth, H.L.; Sheals, K.; Atkins, L.; Jackson, R.; Michie, S. Developing interventions to change recycling behaviors: A case study of applying behavioral science. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2016, 15, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Addo, I.B.; Thoms, M.C.; Parsons, M. Barriers and drivers of household water-conservation behavior: A profiling approach. Water 2018, 10, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allison, A.L.; Ambrose-Dempster, E.; Bawn, M.; Arredondo, M.C.; Chau, C.; Chandler, K.; Dobrijevic, D.; Aparasi, T.D.; Hailes, H.C.; Lettieri, P.; et al. The impact and effectiveness of the general public wearing masks to reduce the spread of pandemics in the UK: A multidisciplinary comparison of single-use masks versus reusable face masks. UCL Open Environ. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, A.L.; Lorencatto, F.; Michie, S.; Miodownik, M. Barriers and Enablers to Buying Biodegradable and Compostable Plastic Packaging. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, A.L.; Lorencatto, F.; Miodownik, M.; Michie, S. Influences on single-use and reusable cup use: A multidisciplinary mixed-methods approach to designing interventions reducing plastic waste. UCL Open Environ. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.M.; Diaz-Artiga, A.; Weinstein, J.R.; Handley, M.A. Designing a behavioral intervention using the COM-B model and the theoretical domains framework to promote gas stove use in rural Guatemala: A formative research study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hedin, B.; Katzeff, C.; Eriksson, E.; Pargman, D. A systematic review of digital behaviour change interventions for more sustainable food consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Kleij, R.; Wijn, R.; Hof, T. An application and empirical test of the Capability Opportunity Motivation-Behaviour model to data leakage prevention in financial organizations. Comput. Secur. 2020, 97, 101970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, W.; Haklay, M.; Lorke, J. Exploring factors associated with participation in citizen science among UK museum visitors aged 40–60: A qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework and the capability opportunity motivation-behaviour model. Public Underst. Sci. 2020, 30, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Collins, K.M. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. Qual. Rep. 2007, 12, 281–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.C.; Caracelli, V.J.; Graham, W.F. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1989, 11, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; Brady, A.-M.; Byrne, G. An overview of mixed methods research. J. Res. Nurs. 2009, 14, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Barriers to integrating quantitative and qualitative research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolific.co. Available online: https://prolific.co/ (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- The Big Compost Experiment. Available online: www.bigcompostexperiment.org.uk (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Qualtrics. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/ (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, N.H.; Bent, D.H.; Hull, C.H. SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1975; Volume 227. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.G. Practical statistics for Medical Research; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GOV.UK. Population of England and Wales. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/1.5 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Office of Nationnal Statistics. Number of UK Households Earning above and below £45,000 Equivalised Annual Gross Income for the Financial Year Ending 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/adhocs/11791numberofukhouseholdsearningaboveandbelow45000equivalisedannualgrossincomeforthefinancialyearending2019 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Office of Nationnal Statistics. Families and Households in the UK: 2020. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/bulletins/familiesandhouseholds/2020 (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Office of Nationnal Statistics. Population Estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: Mid-2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2019estimates (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2019; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK. Home Ownership. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/housing/owning-and-renting/home-ownership/latest (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Office of Nationnal Statistics. Overview of the UK Population: January 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/january2021 (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. English Housing Survey; Ministry of Housing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Coakes, S.J.; Steed, L.G.; Ong, C. SPSS Version 16.0 for Windows: Analysis without Anguish, John Wiley & Sons Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2009.

- Ghinea, C.; Drăgoi, E.N.; Comăniţă, E.-D.; Gavrilescu, M.; Câmpean, T.; Curteanu, S.; Gavrilescu, M. Forecasting municipal solid waste generation using prognostic tools and regression analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Levi, N. Do the rich recycle more? Understanding the link between income inequality and separate waste collection within metropolitan areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, J.; Ebreo, A. What makes a recycler? A comparison of recyclers and nonrecyclers. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.-P.; Aldrich, C. Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilikidou, I.; Delistavrou, A. Utilisation of selected demographics and psychographics in understanding recycling behaviour. Greener Manag. Int. 2001, 34, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansana, F.M. Distinguishing potential recyclers from nonrecyclers: A basis for developing recycling strategies. J. Environ. Educ. 1992, 23, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgerton, E.; McKechnie, J.; Dunleavy, K. Behavioral determinants of household participation in a home composting scheme. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsimbe, P.; Mendoza, H.; Wafula, S.T.; Ndejjo, R. Factors associated with composting of solid waste at household level in Masaka municipality, Central Uganda. J. Environ. Public Health 2018, 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.-T.; Huang, M.-H.; Cheng, B.-Y.; Chiu, R.-J.; Chiang, Y.-T.; Hsu, C.-W.; Ng, E. Applying a comprehensive action determination model to examine the recycling behavior of taipei city residents. Sustainability 2021, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Merodio, J.A.M.; McCallum, S. What role do emotions play in transforming students’ environmental behaviour at school? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.V.; Young, C.W.; Unsworth, K.L.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Mattia, G.; Di Leo, A.; Pratesi, C.A. The household wasteful behaviour framework: A systematic review of consumer food waste. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refsgaard, K.; Magnussen, K. Household behaviour and attitudes with respect to recycling food waste–experiences from focus groups. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.X.; Siu, K.W.M. Challenges in food waste recycling in high-rise buildings and public design for sustainability: A case in Hong Kong. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 131, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, D.; Reinders, M.J.; Molenveld, K.; Onwezen, M.C. The paradox between the environmental appeal of bio-based plastic packaging for consumers and their disposal behaviour. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, J.L.; Steg, L.; van der Werff, E.; Ünal, A.B. A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timlett, R.; Williams, I. The impact of transient populations on recycling behaviour in a densely populated urban environment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.; Szefler, A.; Kelly, C.; Bond, N. Commercial and household food waste separation behaviour and the role of Local Authority: A case study. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Motivating recycling behavior—Which incentives work, and why? Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Rebar, A.L. Habit formation and behavior change. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strohacker, K.; Galarraga, O.; Williams, D.M. The impact of incentives on exercise behavior: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 48, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sigmon, S.C.; Patrick, M.E. The use of financial incentives in promoting smoking cessation. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, S24–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, L.; Bishop, B. A moral basis for recycling: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Timlett, R.E.; Williams, I.D. Public participation and recycling performance in England: A comparison of tools for behaviour change. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, S.; Klöckner, C.A. Social desirability in environmental psychology research: Three meta-analyses. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Corner, A.; Nicholls, J. Britain Talks Climate: A Toolkit for Engaging the British Public on Climate Change. Available online: https://climateoutreach.org/reports/britain-talks-climate/# (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- O’Brien, J.; Thondhlana, G. Plastic bag use in South Africa: Perceptions, practices and potential intervention strategies. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.; Sousa, V.; Vaz, J.; Dias-Ferreira, C. Model for the separate collection of packaging waste in Portuguese low-performing recycling regions. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 216, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A.; Younus, M. Managing plastic waste disposal by assessing consumers’ recycling behavior: The case of a densely populated developing country. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 33054–33066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, A.; Axon, S. “I’ma bit of a waster”: Identifying the enablers of, and barriers to, sustainable food waste practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 24, pp. 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Whitmarsh, L. Habit and climate change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Schwarzer, R.; Scholz, U.; Schüz, B. Action planning and coping planning for long-term lifestyle change: Theory and assessment. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.; Brown, J. Theory of Addiction; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B.F. Operant behavior. Am. Psychol. 1963, 18, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N (Missing) | % | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1801 (0) | ||

| Male | 593 | 32.9 | |

| Female | 1185 | 65.8 | |

| Non-binary | 5 | 0.3 | |

| Prefer not to say | 18 | 1 | |

| Age (years) | 1763 (38) | 56.98 (15.49) | |

| Ethnicity | 1790 (11) | ||

| White or White British | 1674 | 92.9 | |

| Arab or Arab British | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Asian or Asian British | 40 | 2.1 | |

| Black or Black British | 21 | 1.2 | |

| Mixed | 32 | 1.8 | |

| Any other ethnic background | 21 | 1.2 | |

| Highest level of education | 1801 (0) | ||

| Primary education | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Lower secondary education | 56 | 3.1 | |

| Higher secondary education | 164 | 9.1 | |

| Vocational certificate | 157 | 8.7 | |

| Associate degree | 59 | 3.3 | |

| Undergraduate degree | 678 | 37.6 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 474 | 26.3 | |

| PhD/ Doctorate | 212 | 11.8 | |

| Employment status | 1801 (0) | ||

| Retired | 773 | 42 | |

| Employed | 653 | 36 | |

| Self-employed | 191 | 10.6 | |

| Homemaker | 49 | 2.7 | |

| Student | 44 | 2.4 | |

| Out of work (looking for work) | 24 | 1.3 | |

| Unable to work | 23 | 1.3 | |

| Out of work (not looking) | 15 | 0.8 | |

| Other | 29 | 1.6 | |

| Recruitment Method | 1801 (0) | ||

| Social media/email | 1501 | 83.3 | |

| Prolific | 300 | 16.6 | |

| Annual household income pre-tax | 1801 (0) | ||

| Less than £10,000 | 61 | 3.3 | |

| £10,000 to £19,999 | 207 | 11.5 | |

| £20,000 to £29,999 | 255 | 14.2 | |

| £30,000 to £39,999 | 224 | 12.4 | |

| £40,000 to £49,999 | 163 | 9.1 | |

| £50,000 to £59,999 | 137 | 7.6 | |

| £60,000 to £69,999 | 98 | 5.4 | |

| £70,000 to £79,999 | 80 | 4.4 | |

| £80,000 to £89,999 | 58 | 3.2 | |

| £90,000 to £99,999 | 32 | 1.8 | |

| £100,000 to £149,999 | 97 | 5.2 | |

| £150,000 or more | 41 | 2.3 | |

| Prefer not to say | 348 | 19.3 | |

| Housing type | 1801 (0) | ||

| Owned home | 1549 | 86 | |

| Privately rented | 177 | 9.8 | |

| Council housing | 40 | 2.2 | |

| Student accommodation | 6 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 29 | 1.6 | |

| Dwelling type | 1801 (0) | ||

| Detached | 738 | 40.1 | |

| Semi-detached | 551 | 30.6 | |

| Terraced | 318 | 17.6 | |

| Flats non-high rise | 152 | 8.4 | |

| Flats high rise | 13 | 0.7 | |

| Tiny home | 7 | 0.3 | |

| Other (e.g., boat home) | 22 | 1.2 | |

| Number of people in household | 1766 (35) | 2.36 (1.04) | |

| Household relationships | 1801 (0) | ||

| Couple | 760 | 42.2 | |

| Family | 701 | 28.9 | |

| Single person | 265 | 14.7 | |

| Sharing with friends/flatmates | 46 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 29 | 1.6 | |

| Food waste collection services available | 1801 (0) | ||

| Yes | 944 | 52.4 | |

| No | 830 | 46.1 | |

| Unsure | 27 | 1.5 | |

| If YES, use of a food waste caddy | 944 (0) | ||

| Yes | 809 | 85.7 | |

| No | 135 | 14.3 | |

| If YES, frequency of caddy use and; | 809 (0) | ||

| Always | 577 | 71.2 | |

| Most of the time | 123 | 15.2 | |

| About half the time | 23 | 2.8 | |

| Sometimes | 74 | 9.1 | |

| Never | 12 | 1.5 | |

| If YES, use of compostable caddy liners | 809 (0) | ||

| Yes | 555 | 68.6 | |

| No | 185 | 22.8 | |

| Sometimes | 69 | 8.5 | |

| Awareness 2023 food waste scheme | 1801 (0) | ||

| Yes | 375 | 20.8 | |

| No | 1331 | 73.9 | |

| Not sure | 95 | 5.3 | |

| Readiness for 2023 food waste scheme | 1801 (0) | ||

| Yes | 1523 | 84.6 | |

| No | 134 | 7.4 | |

| Not sure | 144 | 7.9 |

| Variable | N (Missing) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 937 (7) | |

| White or White British | 875 | 93.3 |

| Other | 62 | 6.6 |

| Gender | 931 (13) | |

| Woman | 649 | 69.7 |

| Man | 282 | 30.3 |

| Annual household income pre-tax | 742 (202) | |

| £10,000–£29,000 | 258 | 34.8 |

| £30,000–£59,000 | 260 | 35 |

| £69,000 + | 224 | 30.2 |

| Housing type | 944 (0) | |

| Owned home | 836 | 88.6 |

| Other | 108 | 11.4 |

| Dwelling type | 937 (7) | |

| Detached | 386 | 41.2 |

| Semi-detached | 285 | 30.4 |

| Terraced | 193 | 20.6 |

| Flat | 73 | 7.8 |

| Household relationships | 944 (0) | |

| Couple | 381 | 40.4 |

| Family | 384 | 40.7 |

| Single | 38 | 4 |

| Other (e.g., flat-share) | 141 | 14.9 |

| Employment | 944 (0) | |

| Retired | 408 | 43.3 |

| Employed/self-employed | 443 | 46.9 |

| Other (e.g., student) | 93 | 9.9 |

| Education | 944 (0) | |

| Up to associate degree | 226 | 23.9 |

| Undergraduate degree | 362 | 38.3 |

| Postgraduate degree | 356 | 37.7 |

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycling behaviour | 738 | 3.91 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Gender | 738 | 1.32 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Income | 738 | 1.96 | 0.8 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Education | 738 | 2.17 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| House structure | 738 | 1.98 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Psychological capability | 738 | 4.75 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Social opportunity | 738 | 4.18 | 0.74 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Physical opportunity | 738 | 4.48 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Automatic motivation | 738 | 4.43 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Reflective motivation | 738 | 4.12 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Recycling behaviour | - | 0.339 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.204 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.256 ** |

| 2. Psychological capability | - | - | 0.384 ** | 0.618 ** | 0.722 ** | 0.599 ** |

| 3. Social opportunity | - | - | - | 0.308 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.566 ** |

| 4. Physical opportunity | - | - | - | - | 0.486 ** | 0.431 ** |

| 5. Automatic motivation | - | - | - | - | - | 0.655 ** |

| 6. Reflective motivation | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Covariates/Predictors | β | t | sr2 | R | R2 | ∆R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.105 | 0.001 | 0.006 | |||

| Gender | −0.037 | −10.062 | 0.071 | |||

| Income | 0.067 | 10.912 | 0.071 | |||

| Education | −0.08 * | −20.294 | −0.085 | |||

| Structure of housing | 0.048 | 10.363 | 0.05 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.390 | 0.152 | 0.142 | |||

| Psychological Capability | 0.188 *** | 30.345 | 0.123 | |||

| Social Opportunity | 0.058 | 10.378 | 0.051 | |||

| Physical Opportunity | −0.019 | −0.433 | −0.016 | |||

| Automatic Motivation | 0.233 *** | 40.298 | 0.157 | |||

| Reflective Motivation | −0.026 | −0.510 | −0.019 |

| COM-B | Themes | Sub-Themes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical opportunity | Recycles food waste in other ways (n = 97) | - does home composting (n = 76) - feeds food waste to pets/local wildlife (n = 10) - puts it in garden waste (n = 9) - uses neighbour’s bin (n = 2) | “I compost it myself”; “…anything we do not eat goes to birds, foxes/strays...” “It goes in the green garden waste bin, together with perennial weeds, woody garden waste, etc.”; “Very very occasionally we put something (such as meat bones, which we seldom have) into our neighbours’ food recycling bin.” |

| Physical opportunity | Produces no/minimal food waste (n = 20) | “I don’t produce any food waste” | |

| Automatic motivation | Pests/hygiene (n = 18) | - Smell/hygiene (n = 9) - Pests (n = 9) | “The smell and hygiene associated.”; “Our previous experience is that it attracts a lot of flies and unsanitary bacteria to the house.”; “I [don’t] want it to make the house smell or attract mice/rats etc” |

| Physical opportunity | Follows plant-based diet (n = 17) | “Because we eat a vegetarian diet, we put all our food waste in the bin” | |

| Physical opportunity | Cost (n = 15) | - too much effort/hassle to recycle food waste (n = 12) - compostable bags perceived as too expensive (n = 3) | “It’s too much hassle”; “[I] live alone and don’t produce enough food waste to make it worthwhile”; “Living in a small top floor flat, it’s not convenient to store the food waste bin in a small kitchen and have to carry it down stairs. No one in the building (four flats) uses any of the food waste bins—I think for similar reasons.” “The bags the council insist we use inside our food waste bins are so expensive!” |

| Physical opportunity | Service-related factors (n = 12) | - unreliable food waste collection services (n = 9) - council does not provide free food waste bins (n = 2) - council only provides non- compostable bags (n = 1) | “It’s never collected and it stinks”; “We are not given a bin for food waste where we live.”; “Our council supply us with single use polythene bags as liners, rather than compostable material” |

| Physical opportunity | Household related factors (n = 10) | - no space within home (n = 6) - no space for an extra food waste bin outside (n = 2) - no bin at home (n = 1) - not responsible for household decisions (n = 1) | “We don’t have space in our (rented) kitchen for an additional bin on top of the general and recycling bins.”; “I have room for 3 wheelie bins outside my house, but I have 4 bins. I have chosen to leave the food/garden waste bin out of the way in my garage. It therefore doesn’t get used……”; “We don’t have a separate food waste bin” “My parents manage the food waste and they have chosen not to do so. I do not know their reasons for this.” |

| Psychological capability | Lack of knowledge/awareness (n = 4) | - does not understand point of recycling (n = 3) - lacks knowledge on how to recycle food waste (n = 1) | “We just never have, no reason really, would be good to know what happens to food waste what are the benefits of putting it in a separate bin?”; “not sure how to.” |

| COM-B | Themes | Sub-Themes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical opportunity | Repurposing other types of bags/materials (n = 75) | “I use paper bags” “We wrap our food waste in newspaper.” “Stainless steel container and use paper towelling to line it.” | |

| Physical opportunity | Council-related factors (n = 50) | - council accepts non-compostable liners (n = 38) - council does not provide them freely (n = 5) - council does not want them to be used (n = 6) - council provides non-compostable caddy liners (n = 14) - collectors leave waste thinking it is wrapped in plastic (n = 1) | “our local council recycling scheme says we can use any bag for recycling food waste” “They are not provided by the local council, we are a very low income family so its an extra expense we don’t need.” “Our local council do not accept any type of compostable plastic in with the food waste.” “Council provides plastic bags for the purpose—they switched to plastic from starch 2 years ago” “Waste collectors think it is regular plastic and will not collect the bin until the bag is removed” |

| Reflective motivation | Lack of necessity (n = 49) | “Unnecessary additional waste” “No need for a bin liner” “I don’t believe it’s necessary to spend anything further to enable me to dispose of waste.” | |

| Physical opportunity | Accessibility (n = 27) | “…because I am disabled, I cannot always get to the correct supermarket that sells the right type & size of bin liner” “The price” “Quite expensive” | |

| Reflective motivation | Beliefs about environmental impacts (n = 21) | “Even though they are compostable they still are bad for the environment. They require carbon to manufacture, transport etc and I’m not entirely sure whether they break down in “ “…unsure if materials break down as easily as they should” “I use paper bags instead. That way the paper bags are used twice. (and I do not need to use specially made bin liners at all) I believe this is less wasteful.” | |

| Physical opportunity | Cleans food waste bin directly (n = 21) | “We simply wash the container” “In my kitchen bin I use no liner at all, just regularly brush the material into the council bin ready to go out to the kerb later.” “I did not find the compostable food caddy liners you can buy particularly helpful—it is just as easy to empty the food bin into the one council collect.” | |

| Physical opportunity | Availability (n = 15) | “Not always available” “My local shop doesn’t sell them” | |

| Physical opportunity | Design-related factors (n = 12) | “The bin liners are very fragile and tear a lot, wasting bags. I have to pay for them (to not be suitable for what I need)” “They are not always available or big enough” | |

| Psychological capability | Lack of knowledge/awareness (n = 6) | “I don’t know where to get them from” “Wasn’t aware of them or how to use them” | |

| Reflective motivation | Priorities (n = 6) | “Inertia. I’ve not got around to sourcing any.” “I use the depending on what I’m putting in it to make the bin easier to fully empty into my garden waste/food recycling bin.” “Inconvenience and cost of maintaining supply of compostable bags. |

| COM-B | Themes | Sub-Themes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological capability | Scheme awareness/clarity (n = 93) | “Ready in principle, but until details are made public it’s hard to know how it will work for our household” “We have not yet been provided with any information about how this will work in my local area.” | |

| Physical opportunity | Space for the additional responsibility (n = 36) | - headspace (n = 8) | “Sounds like a lot of hassle” “I think my household are currently unprepared as this is something we do not do at the moment and would need to get into the routine of doing.” “…If it means more bins cluttering streets and gardens I should not be pleased” “Limited space in my kitchen already used for normal waste, paper, home compost, glass. So how do [I] organise space for yet another bin?” |

| Reflective motivation | Public need for the scheme (n = 35) | “As an older person I have next to nothing to send to a food waste collection so for me it would be a waste of resources.” “We produce such a small amount of food waste it would generally mean putting out a container with next to nothing in it.” “I currently compost what little food waste that we have and I would very much object to being mandated to change that very satisfactory method.” | |

| Automatic motivation | Pests and pollution (n = 33) | “I see reservations re pollution and smells” “I think [it’s] a great idea, but it is difficult to do. I live in an area with a lot of foxes and other animals that look through the bin and scatter the contents which makes me somewhat hesitant.” “I would like more information. I would wish to [know] the containers were well sealed and very regular and definite collections before I agree” | |

| Reflective motivation | Implementation concerns (n = 20) | - lack of trust in council (n = 8) | “Multi occupancy buildings have challenges with dealing with this and the necessary infrastructure may not be available to support its implementation.” “I personally am ready and willing to recycle food waste separately, however the block of flats that I currently live in do not currently provide recycling bins for other recycling such as plastic or card. Due to this I feel that I would not be ready or able to recycle food waste.” “Our local council does not supply any recycling facilities at all for our block of flats, and has not done so for over a year.” |

| Reflective motivation | Pessimism (n = 5) | “I am not sure if this would actually make a difference” “People still won’t bother” | |

| Psychological capability | Knowledge (n = 3) | “Not sure what can go in food waste recycling.” “…Bit more training on what goes in would be nice.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allison, A.L.; Lorencatto, F.; Michie, S.; Miodownik, M. Barriers and Enablers to Food Waste Recycling: A Mixed Methods Study amongst UK Citizens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052729

Allison AL, Lorencatto F, Michie S, Miodownik M. Barriers and Enablers to Food Waste Recycling: A Mixed Methods Study amongst UK Citizens. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052729

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllison, Ayşe Lisa, Fabiana Lorencatto, Susan Michie, and Mark Miodownik. 2022. "Barriers and Enablers to Food Waste Recycling: A Mixed Methods Study amongst UK Citizens" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052729

APA StyleAllison, A. L., Lorencatto, F., Michie, S., & Miodownik, M. (2022). Barriers and Enablers to Food Waste Recycling: A Mixed Methods Study amongst UK Citizens. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052729