Social Network, Cognition and Participation in Rural Health Governance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

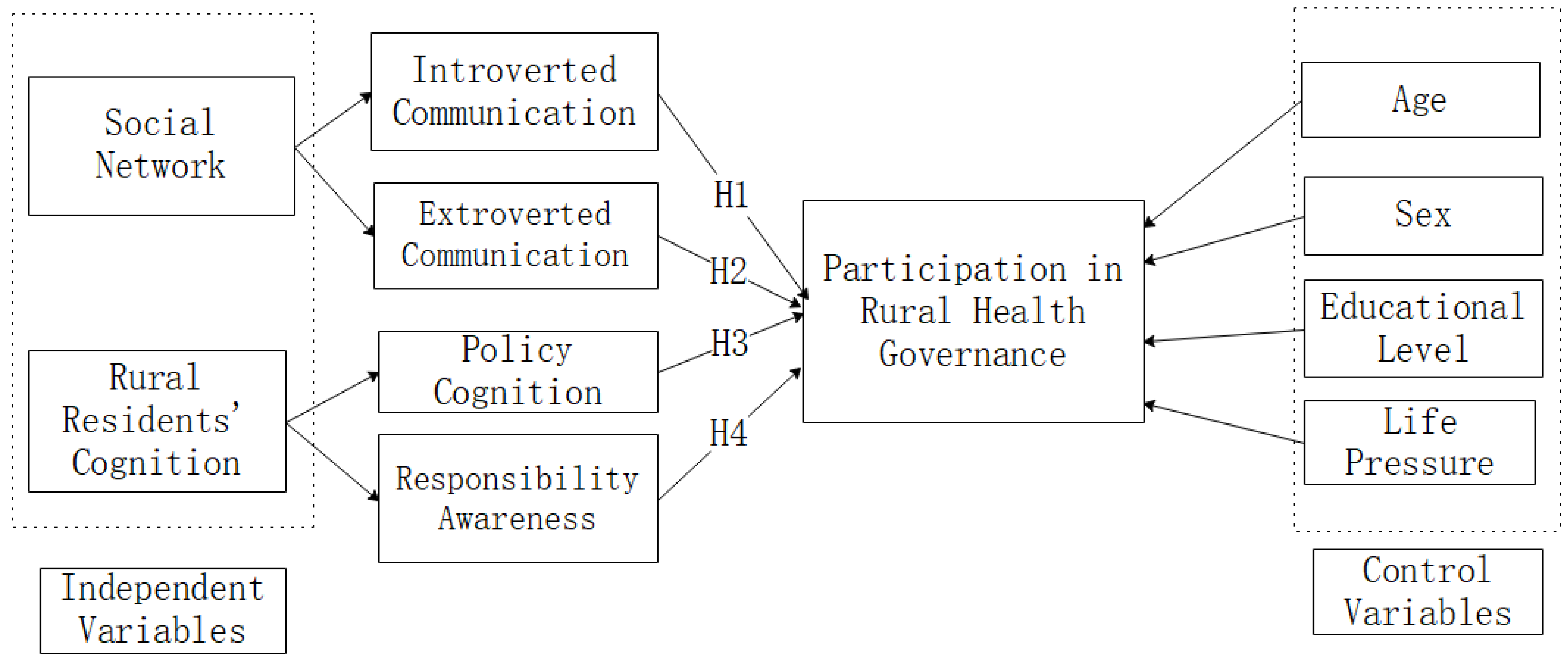

2. Theoretical Backgrounds and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Social Network

2.2. Rural Residents’ Cognition

3. Methods

3.1. Data Sampling

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Rural Residents’ Participation in Rural Health Governance

3.2.2. Social Network

3.2.3. Rural Residents’ Cognition

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Regression Analysis of Rural Residents Participating in Rural Health Governance

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Min, S.; Wang, X.; Hou, L.; Huang, J. The Determinants of Farmers’ Participation in Rural Living Environment Improvement Programs: Evidence from Mountainous Areas in Southwest China. China Rural. Surv. 2019, 4, 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y. Appraisal of typical rural development models during rapid urbanization in the eastern coastal region of China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2009, 19, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Lin, W. Do rural highways narrow Chinese farmers’ income gap among provinces? J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Deng, X.; Li, C.; Yan, Z.; Qi, Y. Do Internet Skills Increase Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Environmental Governance? Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qin, X.; Li, Y. Satisfaction evaluation of rural residentials in northwest China: Method and application. Land 2021, 8, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Li, B.; Fan, M.; Yang, L. How does labor transfer affect environmental pollution in rural China? Evidence from a survey. Energy Econ. 2021, 102, e105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.; Novo, P.; Byg, A.; Creaney, R.; Bourke, A.; Maxwell, J.; Tindale, S.; Waylen, K. Policy instruments for environmental public goods: Interdependencies and hybridity. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, e104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, G.; Mol, A. Implementation and participation in China’s local environmental politics: Challenges and innovations. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, H.; Chen, B.; Xia, X.; Li, P. China’s rural residentials: Qualitative evaluation, quantitative analysis and policy implications. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 105, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomianek, I. Preparation of Local Governments to Implement the Concept of Sustainable Development Against Demographic Changes in Selected Rural and Urban-Rural Communes of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodship. Probl. Zarządzania 2018, 16, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, C. Optimisation of Garbage Bin Layout in Rural Infrastructure for Promoting the Renovation of Rural Residentials: Case Study of Yuding Village in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 21, 11633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, J.; Gaskell, P.; Ingram, J.; Chaplin, S. Understanding farmers’ motivations for providing unsubsidised environmental benefits. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Farmers’ awareness of environmental protection and rural residential environment improvement: A case study of Sichuan province, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Improvement of rural residentials and rural planning strategies from the perspective of public goods. J. Landsc. Res. 2019, 6, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Dai, L.; Deng, L.; Peng, P. Analysis of farmers’ perceptions and behavioral response to rural living environment renovation in a major rice-producing area: A case of Dongting Lake Wetland, China. Cienc. Rural 2021, 51, e20200847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satola, L.; Standar, A.; Kozera, A. Financial autonomy of local government units: Evidence from Polish rural municipalities. Lex Localis J. Local Self-Gov. 2019, 17, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomianek, I. Conditions of Rural Development in the Warmia and Mazury Voivodeship (Poland) in the Opinion of Local Authorities. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Economic Sciences for Agribusiness and Rural Economy, Warsaw, Poland, 7–8 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Standar, A.; Kozera, A.; Satola, L. The Importance of Local Investments Co-Financed by the European Union in the Field of Renewable Energy Sources in Rural Areas of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyburt, A. The activity of local governments in the absorption of EU funds as a factor in the development of rural communes. Acta Sci. Pol. 2014, 13, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, S. Objective and subjective assessments of living standards among members of the rural population. Ann. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. 2016, 103, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Q.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J. Cleaner agricultural production in drinking-water source areas for the control of non-point source pollution in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, e112096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S. Essentials of Chinese Culture; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2003; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X. From the Soil—The Foundations of Chinese Society; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2006; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Qian, X.; Zhang, L. Public participation in environmental management in China: Status quo and mode innovation. Environ. Manag. 2015, 55, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, M.; Feng, S.; Lu, H.; Fan, P. Behavioral Mechanism of Farmers Participation in Rural Domestic Waste Management—Based on the Moderating Effect of the Big Five Personality Traits. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 2236–2250. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, Z.; Reisner, A.; Liu, Y. Compliance with household solid waste management in rural villages in developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. Turning In, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America. Political Sci. Politics 1995, 4, 667. [Google Scholar]

- Okun, M.; Stock, W.; Haring, M.; Witter, R. The social activity/subject well-being relation: A quantitative synthesis. Res. Aging 1984, 1, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth, P.; Ludwig, L. Visual behavior in social interaction. J. Commun. 1972, 22, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Hu, F. Study on the Influence of Social Capital on Farmers’ Participation in Rural Domestic Sewage Treatment in Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 7, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, X. On the Society of Semi-acquaintances—A Perspective for Understanding the Election of Village. Committee. Political Sci. Res. 2000, 3, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Jiao, S. Impacts of Chinese urbanization on farmers’ social networks: Evidence from the urbanization led by farmland requisition in Shanghai. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2016, 2, 05015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Cats as Media: Connections and Barriers of Interpersonal Communication. Beijing Soc. Sci. 2019, 10, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Governance by Force, Gender Preference and Women’s Participation—An Analysis Based on the Status of Women’s Participation in Rural Governance. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES EDITION) 2006, 4, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huhe, N. Understanding the multilevel foundation of social trust in rural China: Evidence from the China General Social Survey. Soc. Sci. Q. 2014, 2, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhe, N.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. Social trust and grassroots governance in rural China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 53, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiu, L.; Xue, J. Cultivation of Chinese Farmers’ Integrity. J. Northeast. Agric. Univ. (Engl. Ed.) 2014, 2, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X. Study on the dilemma and Countermeasures of rural environmental pollution control under the background of Rural Revitalization Strategy. E3S Web Conf. EDP Sci. 2021, 237, 01030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, L. Social support networks and adaptive behaviour choice: A social adaptation model for migrant children in China based on grounded theory. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, e104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, N.; Perkins, D.; Xu, Q. Social capital and community participation among migrant workers in China. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 1, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Q.; Palmer, N. Migrant workers’ community in China: Relationships among social networks, life satisfaction and political participation. Psychosoc. Interv. 2011, 3, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Zhong, W.; Zeng, G.; Wang, S. The reshaping of social relations: Resettled rural residents in Zhenjiang. China. Cities 2017, 60, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Fundamentals of Political Science; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2006; p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, V. Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations; Huaxia Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1989; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 3, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J. Analysis of Farmers’ Political Participation in Professional Cooperatives—Based on the Survey of Model Cooperatives in Zhejiang Province. Agric. Econ. Issues 2009, 9, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Martha, L. Introduction to Political Psychology; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2013; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Kong, X.; Wang, B. Study on Farmers’ Cognition, Institutional Environment and Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in the Renovation of Living Environment—The Intermediary Effect of Information Trust. Resour. Environ. Arid. Areas 2021, 6, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Paudel, K.; Guo, J. Understanding Chinese Farmers’ Participation Behavior Regarding Vegetable Traceability Systems. Food Control 2021, 130, 108325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, A. Peasant conflict and the local predatory state in the Chinese countryside. J. Peasant. Stud. 2007, 34, 560–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K. Formation of Political Psychology and Political Participation; Taiwan Commercial Press: Taipei, China, 1989; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K. Commentary on Sukhomlinsky; People’s Education Press: Beijing, China, 2018; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Xie, L. Environmental activism, Social Networks, and the Internet. China Q. 2009, 198, 422–432. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J. Social supervision, group identity and farmers’ domestic waste centralized disposal behavior: An analysis based on mediation effect and regulating effect of the face concept. China Rural Surv. 2019, 2, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L. Investigation, Research and Reflection on the Social Responsibility of Contemporary College Students. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2016, 6, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, E.; Howley, P. The accidental environmentalists: Factors affecting farmers’ adoption of pro-environmental activities in England and Ontario. Rural Study 2019, 68, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. A Study on the Political Participation of Chinese Peasants from a Revolutionary Perspective. The History and Logic of Modern Chinese Politics; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X. How does soil pollution risk perception affect farmers’ pro-environmental behavior? The role of income level. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Change in Rural Control Mode and Peasants’ Mandatory Non-Institutional Political Participation during the Transformation Period. Non-Institutional Political Participation; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 87–137. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, G.; Xia, W. How Do Network Embeddedness and Environmental Awareness Affect Farmers’ Participation in Improving Rural Residentials? Land 2021, 10, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T. The meaning of social capital and its link to collective action. Handb. Soc. Cap. Troika Sociol. Political Sci. Econ. 2009, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ataei, P.; Sadighi, H.; Chizari, M.; Abbasi, E. Analysis of Farmers’ Social Interactions to Apply Principles of Conservation Agriculture in Iran: Application of Social Network Analysis. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 1657–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of environmental cognition and environmental attitude on environmental behavior of ecotourism. Ekoloji 2018, 27, 1743–1749. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Long, Q. Prediction of environmental cognition to undesired environmental behavior—the interaction effect of environmental context. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Juknys, R. The role of values, environmental risk perception, awareness of consequences, and willingness to assume responsibility for environmentally-friendly behaviour: The Lithuanian case. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3413–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Qiu, M.; Zhou, M. Correlation between general health knowledge and sanitation improvements: Evidence from rural China. NPJ Clean Water 2021, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiewski, J.; Takala, J.; Juszczyk, O.; Drejerska, N. Local contribution to circular economy. A case study of a Polish rural municipality. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2019, 21, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Hu, L.; Zheng, W.; Yao, S.; Qian, L. Impact of household land endowment and environmental cognition on the willingness to implement straw incorporation in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; He, K.; Li, W. Place attachment, environmental cognition and organic fertilizer adoption of farmers: Evidence from rural China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 41255–41267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruysers, S.; Blais, J.; Chen, P. Who makes a good citizen? The role of personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 146, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.; Martin, E. Sense of community responsibility at the forefront of crisis management. Adm. Theory Prax. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic Index | Classification | Frequency | Proportion (%) | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1527 | 65.17 | 0.48 |

| Female | 816 | 34.83 | ||

| Age | Below 30 | 109 | 4.65 | 1.14 |

| 30–39 | 187 | 7.98 | ||

| 40–49 | 448 | 19.12 | ||

| 50–59 | 711 | 30.35 | ||

| 60 and above | 888 | 37.90 | ||

| Occupation | Farming | 1523 | 65.00 | 1.60 |

| Working | 372 | 15.88 | ||

| Teaching | 29 | 1.24 | ||

| Self-employed and private business owners | 154 | 6.57 | ||

| Rural managing | 58 | 2.48 | ||

| Other | 207 | 8.83 | ||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 134 | 5.72 | 0.62 |

| Married | 1976 | 84.34 | ||

| Divorced | 41 | 1.75 | ||

| Widowed | 192 | 8.19 | ||

| Region | Eastern | 383 | 16.35 | 0.69 |

| Middle | 1143 | 48.78 | ||

| Western | 817 | 34.87 | ||

| In total | 2343 | 100 | ||

| Variables | Variable Name | Operational Processing | Valuation | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Participation in rural health governance | Participate in the governance or not | No = 0; Yes = 1 | 0.28 | 0.45 |

| Control variable | Sex | Your sex | Female = 0; Male = 1 | 0.65 | 0.48 |

| Age | Your age | Below 30 =1; 30–39 = 2; 40–49 = 3; 50–59 = 4; 60 and above = 5 | 3.89 | 1.14 | |

| Educational level | Your educational level | Illiterate = 1; Primary school = 2; Junior high school = 3; High school =4; College degree or above = 5 | 2.64 | 0.95 | |

| Life pressure | Your life pressure | No = 1; Little = 2; General = 3; High = 4; Very high = 5 | 3.44 | 0.90 | |

| Social network | Introverted communication | Human relation pressure | Very small = 1; Small = 2; General = 3; large = 4; Very large = 5 | 3.56 | 0.93 |

| Extraverted communication | Outgoing frequency | No = 1; Seldom = 2; General = 3; Often = 4; Frequent = 5 | 2.82 | 0.98 | |

| Residents’cognition | Policy cognition | Related policy cognition | No = 1; Little = 2; General = 3; Clear = 4; Very clear = 5 | 2.60 | 1.11 |

| Remediation project cognition | No = 1; Little = 2; General = 3; Clear = 4; Very clear = 5 | 2.66 | 1.05 | ||

| Responsibility awareness | Responsibility identity cognition | Very disagree = 1; Disagree = 2; General = 3; Agree = 4; Very agree = 5 | 4.20 | 0.72 | |

| Responsibility expression | No = 0; Yes = 1 | 0.21 | 0.41 | ||

| Willingness in expression | Unwilling = 0; Willing = 1 | 0.76 | 0.43 |

| Related Policy Cognition | Participation | Responsibility Expression | Participation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| No | 80.68 | 19.32 | No | 79.67 | 20.33 |

| Little | 77.94 | 22.06 | |||

| General | 72.28 | 27.72 | |||

| Clear | 59.00 | 41.00 | Yes | 41.22 | 58.78 |

| Very clear | 36.96 | 63.04 | |||

| Sample: 2334; p = 0.000 | Sample: 2325; p = 0.000 | ||||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Standard Error | β | Standard Error | β | Standard Error | |

| Control variable | ||||||

| Sex a | 0.249 * | 0.101 | 0.282 ** | 0.103 | 0.137 | 0.112 |

| Age | 0.018 | 0.047 | −0.008 | 0.048 | −0.010 | 0.052 |

| Educational level | 0.162 ** | 0.055 | 0.188 *** | 0.056 | 0.057 | 0.062 |

| Life pressure | 0.232 *** | 0.054 | 0.157 ** | 0.057 | 0.181 ** | 0.062 |

| Social network | ||||||

| Human relation pressure | 0.240 *** | 0.054 | 0.240 *** | 0.059 | ||

| Outgoing frequency | −0.214 *** | 0.050 | −0.236 *** | 0.054 | ||

| Policy cognition | ||||||

| Related policy cognition | 0.152 * | 0.077 | ||||

| Remediation project cognition | 0.208 * | 0.082 | ||||

| Responsibility awareness | ||||||

| Responsibility identity cognition | 0.374 ** | 0.079 | ||||

| Responsibility expression b | 1.465 ** | 0.119 | ||||

| Willingness in expression c | 0.472 ** | 0.143 | ||||

| constant | −2.644 *** | 0.379 | −2.674 | 0.425 | −5.288 *** | 0.562 |

| Model fitting | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 2730.294 | 2672.956 | 2304.253 | |||

| Nagelkerke R | 0.024 | 0.046 | 0.241 | |||

| Valid sample | 2316 | 2277 | 2277 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, J.; Ruan, H.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Li, C.; Dong, X. Social Network, Cognition and Participation in Rural Health Governance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052862

Tang J, Ruan H, Wang C, Xu W, Li C, Dong X. Social Network, Cognition and Participation in Rural Health Governance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052862

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Jiayi, Haibo Ruan, Chao Wang, Wendong Xu, Changgui Li, and Xuan Dong. 2022. "Social Network, Cognition and Participation in Rural Health Governance" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052862

APA StyleTang, J., Ruan, H., Wang, C., Xu, W., Li, C., & Dong, X. (2022). Social Network, Cognition and Participation in Rural Health Governance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052862