Development of Teacher Rating Scale of Risky Play for 3- to 6-Year-Old Pre-Schoolers in Anji Play Kindergartens of East China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Anji Play

1.2. Risky Play among Pre-Schoolers

1.3. Measurements of Risky Play

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures of the TRSRP Construction

- Observations: Through non-participatory and participatory ways, the outdoor activities of pre-schoolers of 9 classes in three Anji play kindergartens were observed for 6 weeks. In China, there are typically three levels of classes: Lower Kindergarten Class for Aged 3–4 children (Xiaoban), Middle Kindergarten Class for Aged 4–5 children (Zhongban), and Upper Kindergarten Class for Aged 5–6 children (Daban). In each kindergarten, three classes (one Xiaoban, one Zhongban, one Daban) participated in this stage. The teachers in each class were instructed to record video clips of children’s risk play (the behaviour they regarded as risk in the play). Relevant pictures were taken to indicate the details of the setting and observations were recorded in written form. In sum, each set of risky play behaviour record included video clips, 1–2 pictures and an observation record. The teachers of each class collected about 22 sets of records. A total of 200 sets of risky play were collected. Those records were used for the classification and level description construction.

- Interviews: The principle and five teachers in each kindergarten, covering three levels of classes (Xiaoban, Zhongban, Daban), were invited to participate in the interview. A total of 15 teachers and 3 principals of three Anji play kindergarten were interviewed. The content of the interviews mainly concerned the typical performance of children in play of bucket/vertical jump/balance beam walking/climbing/slide/high-speed swing/high-speed ride/high-speed running. Those interviews were used for the construction and modification of the TRSRP.

2.1.1. Type Determination

2.1.2. Development of Risky Play Sub-Types and Level Descriptions

2.1.3. Evaluation of Content Validity and Finalization of TRSRP

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Validity of the TRSRP

3.1.1. Content Validity

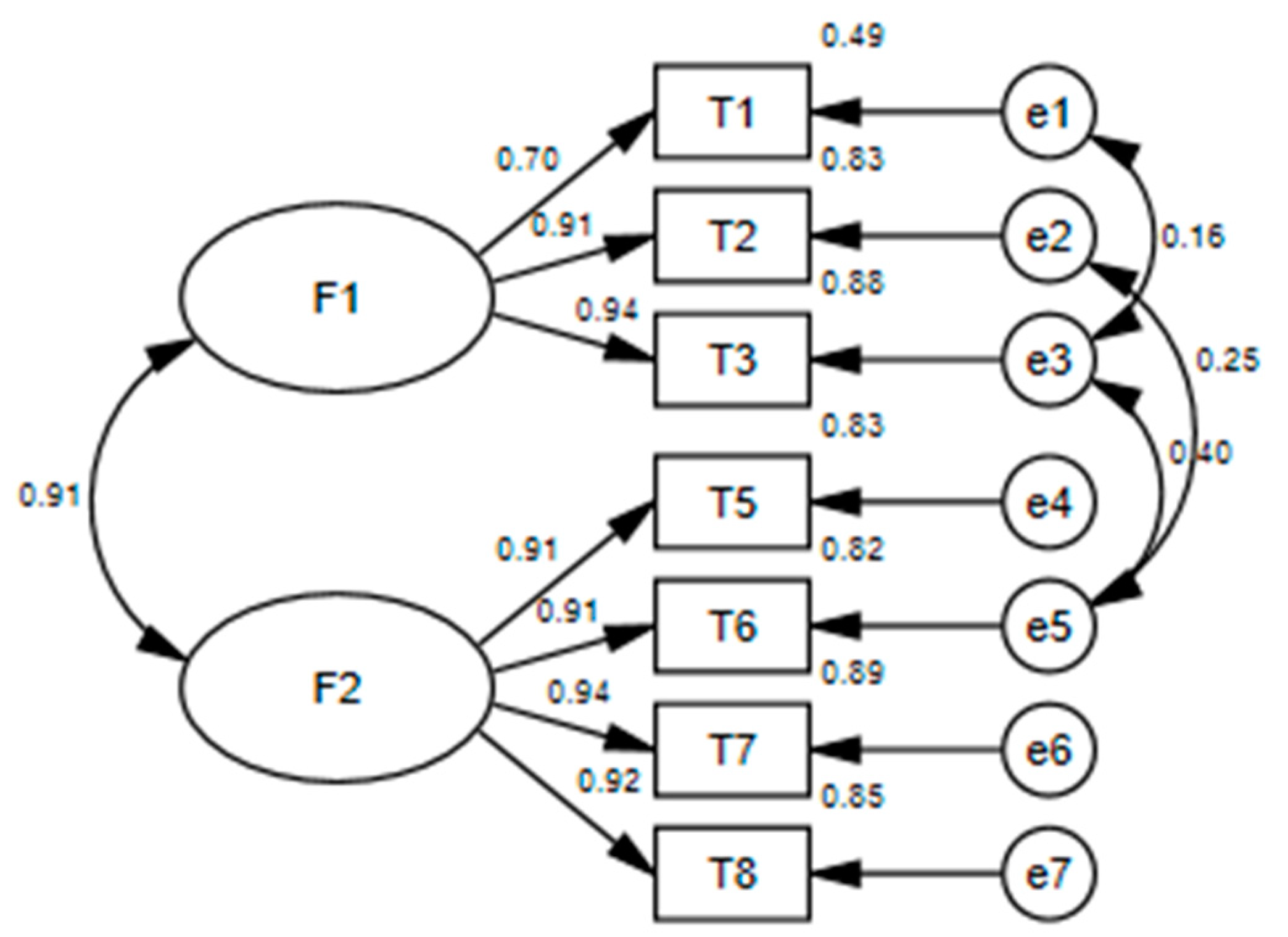

3.1.2. Construct Validity

3.2. Reliability of the TRSRP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type and Level Descriptions |

|---|

| Playing with buckets |

| 1. Elementary: pushing the buckets with hands, pushing the bucket with a partner, climbing in a single bucket, curling up and rolling in the bucket, playing the game of whack-a-mole with the bucket upright, etc. |

| 2. Pre-intermediate: climbing in multiple buckets that have been arranged and combined, walking on multiple buckets that have been fixed and combined, etc. |

| 3. Intermediate: with the protective mat in front or with the help of teachers or partners, try to stand on the bucket in various ways and start learning how to walk on the bucket. |

| 4. Upper-intermediate: able to walk on buckets independently, flexibly and confidently. |

| 5. Advanced: if there is a huddled companion in the bucket, the child can also walk on the bucket; able to jump to another bucket to continue walking; walk on the bucket hand in hand with the partner; while standing on the bucket, play other games, such as passing the ball, playing hula hoop and so on. |

| Vertical jump |

| 1. Elementary: children observe the behaviour of their peers jumping from a height. They try to stand at a height of 40–50 cm and want to jump down, but they are always hesitant, and finally fail to jump down. |

| 2. Pre-intermediate: a protective mat is put on the ground, and the child can jump down from a height of 70–80 cm. |

| 3. Intermediate: a protective mat is put on the ground, and the child can jump down from a height of 100–110 cm. |

| 4. Upper-intermediate: a protective mat is put on the ground, and the children can jump down from a height of about 130–140 cm, flexibly and confidently. |

| 5. Advanced: a protective mat is put on the ground, and the children can jump down from a height of about 150 cm or even higher. |

| Balance beam walking (The balance beam is 200 cm long, and 20 cm wide) |

| 1. Elementary: with a protective mat on the ground, the child tries to walk on a balance beam at a height of 40–50 cm from the ground, with or without the support of a companion or an adult. |

| 2. Pre-intermediate: when there is a protective pad on the ground, the child can walk alone from the balance beam at a height of 60 cm to 70 cm above the ground, but he or she may walk slowly and is slightly nervous. |

| 3. Intermediate: when there is a protective pad on the ground, the child can walk independently, flexibly and confidently from a balance beam with a height of 80 cm to 90 cm. |

| 4. Upper-intermediate: when there is a protective pad on the ground, the child can challenge to walk on a balance beam with a height of 100–110 cm, but he or she may bend his or her waist to walk slowly because of fear. |

| 5. Advanced: when there is a protective pad on the ground, able to walk through the balance beam of 120–130 cm above the ground independently, flexibly, confidently and quickly. |

| High-speed swing (Take swing as an example) |

| 1. Elementary: children sit on a swing with the help of their peers or teachers, and the swing range is 30–45 degrees. |

| 2. Pre-intermediate: children sit on a swing with the support of their peers or teachers, and the swing range is 45–60 degrees. |

| 3. Intermediate: children sit on a swing with the support of their peers or teachers to swing, and the swing range is 60–75 degrees. |

| 4. Upper-intermediate: the ways of swinging are more diversified. For example, with the support of peers or teachers, one child can squat on the swing, and the swing range is about 45 degrees; or stand on the swing, and the swing range is about 30 degrees; or a fast circular swing; or a contest of who can swing fast and high. |

| 5. Advanced: there is a protective cushion in front, and the child flies out of the swing and jumps on the cushion, and even make a competition of “see who can fly farther” or perform aerial modelling to see whose pose is more difficult. |

| High-speed slide (Take slide as an example. he long board is 200 cm long and 20 cm wide.) |

| 1. Elementary: slide down from a self-built slide with a height of 50–60 cm. |

| 2. Pre-intermediate: slide down from a self-built slide with a height of 70–80 cm. |

| 3. Intermediate: slide down from a self-built slide with a height of about 90–100 cm. |

| 4. Upper-intermediate: slide down from a self-built slide with a height of 110–120 cm. |

| 5. Advanced: slide down a self-built slide of 150 cm or higher. |

| High-speed ride (Take tricycle play as an example) |

| 1. Elementary: children can ride at a moderate speed (1 m/s speed) but cannot turn flexibly and avoid obstacles. |

| 2. Pre-intermediate: young children can ride at a relatively fast speed (1.5 m/s) on complex road (such as steep slopes, road with obstacles or narrow road), but need to slow down for safe passage when meeting obstacles or narrow sections. |

| 3. Intermediate: able to compete with peers to see who can ride the fastest; or play a chase game by bike; or while riding a bike, a partner is pushing a tricycle behind to maximize the riding speed (greater than 1.5 m/s). |

| 4. Upper-intermediate: it is possible to easily ride on complex sections of road (such as steep slopes, sections with obstacles or narrow sections) at a speed of more than 1.5 m/s with people or loads. Even if encounter obstacles or narrow sections, the child can also maintain the original speed and control the handlebars for safe riding. |

| 5. Advanced: after the front wheels of several tricycles are stuck in the carriage of the preceding tricycle in a row, each child sits on his own tricycle, and there may be children behind him who are pushing the tricycle, trying to reach the fastest speed to start the “train”. |

| High-speed running |

| 1. Elementary: run at a speed of 2.5 m/s, mainly in small steps with uneven stride, no rhythm, heavy footsteps, and heels on the ground. Two arms cannot naturally swing with the movements of the feet, and the ability to run fast is obviously insufficient. |

| 2. Pre-intermediate: run at a speed of 3 m/s, with heels on the ground, and small stride, and the upper and lower limbs can cooperate more harmoniously, with a certain ability to run fast; |

| 3. Intermediate: run at a speed of 3.5 m/s, the arms and lower limbs are out of position, the elbow joints and the legs are almost fully extended, and the ability to run fast and dodge is improved. |

| 4. Upper-intermediate: able to run at a speed of 4 m/s, the forefoot is on the ground, the arms and lower limbs are out of position, the arms swing obviously, the stride is large and rhythmic, the movements are more coordinated, the flight phase is more obvious, there is a significant improvement in the ability to control the running direction and run, and it is more flexible to turn around, stop and dodge during high-speed running. |

| 5. Advanced: when carrying certain items with both hands, such as a basketball, the child can still run left and right at a speed of 4 m/s, and it is more flexible to turn around, stop and dodge during high-speed running. |

References

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Scaryfunny: A Qualitative Study of Risky Play Among Preschool Children. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Children’s expressions of exhilaration and fear in risky play. Contemp. Issues Early Child 2009, 15, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coster, D.; Gleave, J. Give Us a Go! Children and Young People’s Views on Play and Risk-Taking; Play England by the National Children’s Bureau: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry Education of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3327/200107/t20010702_81984.html (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Cheng, X. Letting Children Play and Discover Them through Play, 1st ed.; East China Normal University Press: Shanghai, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. “Course-based Game” or “Game-based Curriculum”: The Value Orientation Behind the Proposition. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 2019, 12, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry Education of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/moe_164/202102/t20210203_512419.html (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/02/schools-of-the-future-report-2020-education-changing-world/?from=singlemessage (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fjørtoft, I. Landscape and Playscape. Learning Effects from Playing in a Natural Environment on Motor Development in Children. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian School of Sport Science, Oslo, Norway, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrysen, A.; Bertrands, E.; Leyssen, L.; Smets, L.; Vanderspikken, A.; De Graef, P. Risky-play at school. Facilitating risk perception and competence in young children. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J 2015, 25, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y. The present situation and improvement of adventure games of children in kindergarten. Stud. Presch. Educ. 2020, 12, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H.; Wyver, S. Outdoor play: Does avoiding the risks reduce the benefits? J. Early Child 2008, 33, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics; American Public Health Association; National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. Preventing Childhood Obesity in Early Care and Education: Selected Standards from Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs, 3rd ed.; National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education: Aurora, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, A. I’m Not Scared! Risk and Challenge in Children’s Programs; National Childcare Accreditation Council: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tovey, H. Playing on the edge: Perceptions of risk and danger in outdoor play. In Play and Learning in the Early Years; Broadhead, P., Howard, J., Wood, E., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2010; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Affrunti, N.W.; Ginsburg, G.S. Maternal overcontrol and child anxiety: The mediating role of perceived competence. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bayer, J.K.; Hastings, P.D.; Sanson, A.V.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Rubin, K.H. Predicting mid-childhood internalising symptoms: A longitudinal community study. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2010, 12, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N.B.; Dollar, J.M.; Calkins, S.D.; Keane, S.P.; Shanahan, L. Childhood self-regulation as a mechanism through which early overcontrolling parenting is associated with adjustment in preadolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffrin, H.H.; Liss, M.; Miles-McLean, H.; Geary, K.A.; Erchull, M.J.; Tashner, T. Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2004, 23, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, B.S. Intimate Fathers: The Nature and Context of Aka Pygmy Paternal Infant Care; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, A. The Afterlife Is Where We Come from: The Culture of Infancy in West Africa; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- New, R.S.; Mardell, B.; Robinson, D. Early Childhood Education as Risky Business: Going Beyond What’s “Safe” to Discovering What’s Possible. Early Child. Res. Pract. 2005, 7, n2. [Google Scholar]

- Little, H.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Wyver, S. Early childhood teachers’ beliefs about children’s risky play in Australia and Norway. Contemp. Issues Early Child 2012, 13, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Exploration and Comparison of Risky Play in Kindergartens—Taking Norway and Anji, Shanghai Kindergartens as Examples; East China Normal University: Shanghai, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guldberg, H. Reclaiming Childhood: Freedom and Play in an Age of Fear; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarby, K.M.E. Children playing in nature. In Proceedings of the 1st CECDE International Conference: Questions of Quality, Dublin Castle, Ireland, 23–25 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Categorizing risky play—How can we identify risk-taking in children’s play? Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 15, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppe, R.; Melhuish, E.; Sandseter, E.B.H. Identifying and characterizing risky play in the age one-to-three years. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 53, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H.; Eager, D. Risk, challenge and safety: Implications for play quality and playground design. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurt, Ö.; Keleş, S. How about a risky play? Investigation of risk levels desired by children and perceived mother monitoring. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 191, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kleppe, R.; Sando, O.J. The Prevalence of Risky Play in Young Children’s Indoor and Outdoor Free Play. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 49, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.R.A. Cronbach’s alpha: A tool for assessing the reliability of scales. J. Ext. 1999, 37, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ailken, L.R.; Groth-Marnat, G. Psychological Testing and Assessment, 12th ed.; Pearson Education US: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.R.; Davidshofer, C.O. Psychological Testing: Principles and Applications, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| Types | Subtypes and Definitions |

|---|---|

| Play with great heights | Playing with buckets: a play that uses buckets as materials. Usually, pre-schoolers can push the buckets, crawl inside the buckets and walk on the buckets. |

| Vertical jump: a play in which children stand on a platform of a certain height and jump down. | |

| Balance beam walking: a play in which children walk on balance beams of different heights. | |

| Climbing: a play in which climbing, and scrambling are the main movements. | |

| Play with high speed | High-speed swing: a play in which children swing from low to high on a swing in a variety of positions. |

| High-speed sliding: a play in which children use long boards to construct different slopes for sliding. | |

| High-speed ride: a play in which children use tricycles to ride at high speed. | |

| High-speed running: a play in which running is performed at a high speed. |

| Factors | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | ||

| Playing with buckets | 0.82 | |

| Vertical jump | 0.89 | |

| Balance beam walking | 0.75 | |

| Factor 2 | ||

| High-speed swing | 0.87 | |

| High-speed slide | 0.86 | |

| High-speed ride | 0.89 | |

| High-speed running | 0.84 | |

| Eigenvalues | 1.41 | 8.66 |

| % of the variance explained | 11.26 | 69.26 |

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | NFI | RFI | CFI | IFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-factor model | 50.21 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, W.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; He, H. Development of Teacher Rating Scale of Risky Play for 3- to 6-Year-Old Pre-Schoolers in Anji Play Kindergartens of East China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052959

Lin W, Wu J, Wu Y, He H. Development of Teacher Rating Scale of Risky Play for 3- to 6-Year-Old Pre-Schoolers in Anji Play Kindergartens of East China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052959

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Wenqi, Jianfen Wu, Yunpeng Wu, and Hongli He. 2022. "Development of Teacher Rating Scale of Risky Play for 3- to 6-Year-Old Pre-Schoolers in Anji Play Kindergartens of East China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052959

APA StyleLin, W., Wu, J., Wu, Y., & He, H. (2022). Development of Teacher Rating Scale of Risky Play for 3- to 6-Year-Old Pre-Schoolers in Anji Play Kindergartens of East China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2959. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052959