‘Shall We Send a Panda?’ A Practical Guide to Engaging Schools in Research: Learning from Large-Scale Mental Health Intervention Trials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Schools as a Site for Health and Prevention Research

1.2. The Complexity of Schools

1.3. The Importance of Staff Engagement

1.4. Competing Priorities

1.5. The Education for Wellbeing Programme

2. Key Learning

2.1. General Challenges

2.1.1. Recruitment

2.1.2. School Attrition

2.1.3. Understanding the Specific Challenges of Your Research

2.2. Staff Engagement

2.3. Communicating with School Staff

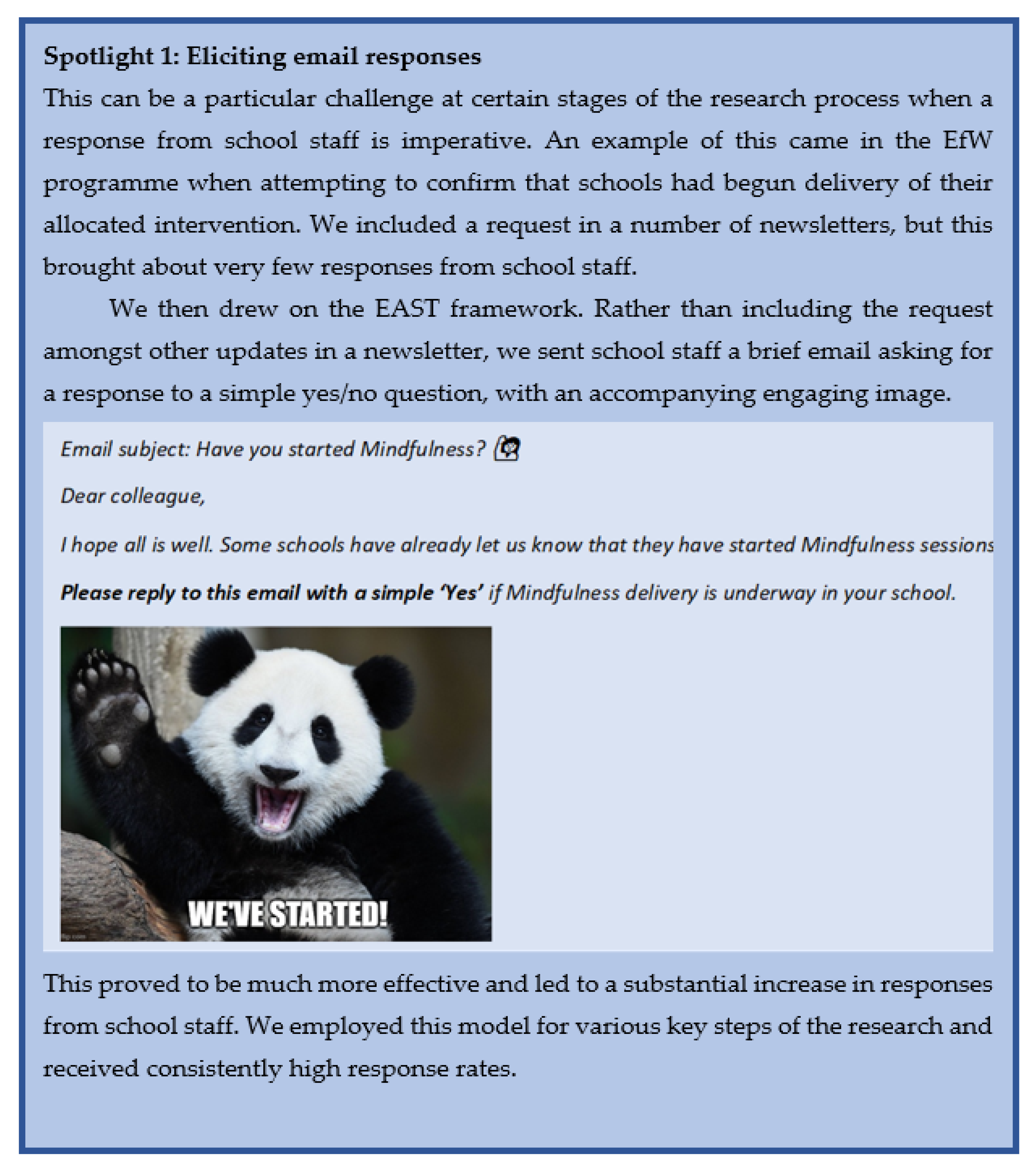

2.3.1. Emails

2.3.2. Phone Calls

2.3.3. Contacting the Right People

2.3.4. Staff Turnover

2.3.5. Large Research Projects

2.4. Quantitative Research

2.5. Qualitative Research

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartlett, R.; Wright, T.; Olarinde, T.; Holmes, T.; Beamon, E.R.; Wallace, D. Schools as Sites for Recruiting Participants and Implementing Research. J. Community Health Nurs. 2017, 34, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, T. Teachers’ engagement with research texts: Beyond instrumental, conceptual or strategic use. J. Educ. Teach. 2015, 41, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishna, F.; Muskat, B.; Cook, C. Anticipating challenges: School-based social work intervention research. Child. Sch. 2012, 34, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlitz, L.; Macintyre, H.; Osborn, T.; Bonell, C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dix, K.L.; Slee, P.T.; Lawson, M.J.; Keeves, J.P. Implementation quality of whole-school mental health promotion and students’ academic performance. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2012, 17, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofsted. Making the Cut: How Schools Respond When They Are under Financial Pressure. February 2020. Available online: www.gov.uk/government/publications/amanda-spielman-letter-to-the-public-accounts-committee (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Sellen, P. Teacher Workload and Professional Development in England’s Secondary Schools: Insights from TALIS. 2016. Available online: http://epi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/TeacherWorkload_EPI.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bruzzese, J.M.; Gallagher, R.; McCann-Doyle, S.; Reiss, P.T.; Wijetunga, N.A. Effective methods to improve recruitment and retention in school-based substance use prevention studies. J. Sch. Health 2009, 79, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, N.; Hennessey, A.; Lendrum, A.; Wigelsworth, M.; Turner, A.; Panayiotou, M.; Joyce, C.; Pert, K.; Stephens, E.; Wo, L.; et al. The PATHS curriculum for promoting social and emotional well-being among children aged 7–9 years: A cluster RCT. Public Health Res. 2018, 6, 1–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshavarz, N.; Nutbeam, D.; Rowling, L.; Khavarpour, F. Schools as social complex adaptive systems: A new way to understand the challenges of introducing the health promoting schools concept. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domitrovich, C.E.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Poduska, J.M.; Hoagwood, K.; Buckley, J.A.; Olin, S.; Romanelli, L.H.; Leaf, P.J.; Greenberg, M.T.; Ialongo, N.S. Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: A conceptual framework. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2008, 1, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, G.A.; Askell-Williams, H. Sustainable school-improvement in complex adaptive systems: A scoping review. Rev. Educ. 2020, 9, 281–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. What is complexity theory and what are its implications for educational change? Educ. Philos. Theory 2008, 40, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.R.; Cowhy, J.; Stevens, W.D.; Sporte, S.E. Designing and Implementing the Next Generation of Teacher Evaluation Systems: Lessons Learned from Case Studies in Five Illinois Districts. Research Brief. Consortium on Chicago School Research. November 2012. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,url,uid&db=eric&AN=ED542563&site=ehost-live&scope=site (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Wilkins, A. Rescaling the local: Multi-academy trusts, private monopoly and statecraft in England. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 2017, 49, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibali, M.W.; Nathan, M.J. Conducting research in schools: A practical guide. J. Cogn. Dev. 2010, 11, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.D. Successful entry and collaboration in school-based research: Tips from a school administrator. Child. Sch. 2007, 29, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.; Moore, A.; Stapley, E.; Humphrey, N.; Mansfield, R.; Santos, J.; Ashworth, E.; Patalay, P.; Bonin, E.-M.; Moltrecht, B.; et al. Promoting mental health and wellbeing in schools: Examining Mindfulness, Relaxation and Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing in English primary and secondary schools: Study protocol for a multi-school, cluster randomised controlled trial (INSPIRE). Trials 2019, 20, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, D.; Moore, A.; Stapley, E.; Humphrey, N.; Mansfield, R.; Santos, J.; Ashworth, E.; Patalay, P.; Bonin, E.; Boehnke, J.R.; et al. School-based intervention study examining approaches for well-being and mental health literacy of pupils in Year 9 in England: Study protocol for a multischool, parallel group cluster randomised controlled trial (AWARE). BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, K.; Vizard, T.; Ford, T.; Goodman, A.; Goodman, R.; McManus, S. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017: Summary of key findings. Community 2018, 2018, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, R.; Bonnell, C.P.; Jones, H.E.; Pouliou, T.; Murphy, S.M.; Waters, E.; Komro, K.A.; Gibbs, L.F.; Magnus, D.; Campbell, R. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD008958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education. November 2019; pp. 1–6. Available online: https://consult.education.gov.uk/pshe/relationships-education-rse-health-education/supporting_documents/20170718_ Draft guidance for consultation.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A Green Paper. 2017; Volume 110. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/transforming-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-provision-a-green-paper (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Behavioural Insights Team. EAST: Four Simple Ways to Apply Behavioural Insights; Behavioural Insight Team: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Demkowicz, O.; Ashworth, E.; Mansfield, R.; Stapley, E.; Miles, H.; Hayes, D.; Burrell, K.; Moore, A.; Deighton, J. Children and young people’s experiences of completing mental health and wellbeing measures for research: Learning from two school-based pilot projects. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, J.R.; Brown, C.; Ion, G.; van Ackeren, I.; Bremm, N.; Luzmore, R.; Flood, J.; Rind, G.M. World-wide barriers and enablers to achieving evidence-informed practice in education: What can be learnt from Spain, England, the United States, and Germany? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Patel, V.; Thomas, S.; Tol, W. Mental health interventions in schools in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Challenge | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. General challenges |

|

|

| 2. Staff engagement |

|

|

| 3. Communicating with school staff |

|

|

| 4. Quantitative research |

|

|

| 5. Qualitative research |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

March, A.; Ashworth, E.; Mason, C.; Santos, J.; Mansfield, R.; Stapley, E.; Deighton, J.; Humphrey, N.; Tait, N.; Hayes, D. ‘Shall We Send a Panda?’ A Practical Guide to Engaging Schools in Research: Learning from Large-Scale Mental Health Intervention Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063367

March A, Ashworth E, Mason C, Santos J, Mansfield R, Stapley E, Deighton J, Humphrey N, Tait N, Hayes D. ‘Shall We Send a Panda?’ A Practical Guide to Engaging Schools in Research: Learning from Large-Scale Mental Health Intervention Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063367

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarch, Anna, Emma Ashworth, Carla Mason, Joao Santos, Rosie Mansfield, Emily Stapley, Jessica Deighton, Neil Humphrey, Nick Tait, and Daniel Hayes. 2022. "‘Shall We Send a Panda?’ A Practical Guide to Engaging Schools in Research: Learning from Large-Scale Mental Health Intervention Trials" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063367

APA StyleMarch, A., Ashworth, E., Mason, C., Santos, J., Mansfield, R., Stapley, E., Deighton, J., Humphrey, N., Tait, N., & Hayes, D. (2022). ‘Shall We Send a Panda?’ A Practical Guide to Engaging Schools in Research: Learning from Large-Scale Mental Health Intervention Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3367. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063367