Enotourism in Southern Spain: The Montilla-Moriles PDO

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. PDOs and Gastronomic Routes

- Gastronomic routes by product, which are routes organized on the basis of a specific product, e.g., cheese, oil, and wine;

- Gastronomic routes by dish, which are organized around the most important prepared dishes;

- Ethnic-gastronomic routes, which are ventures based on the culinary traditions of immigrant peoples.

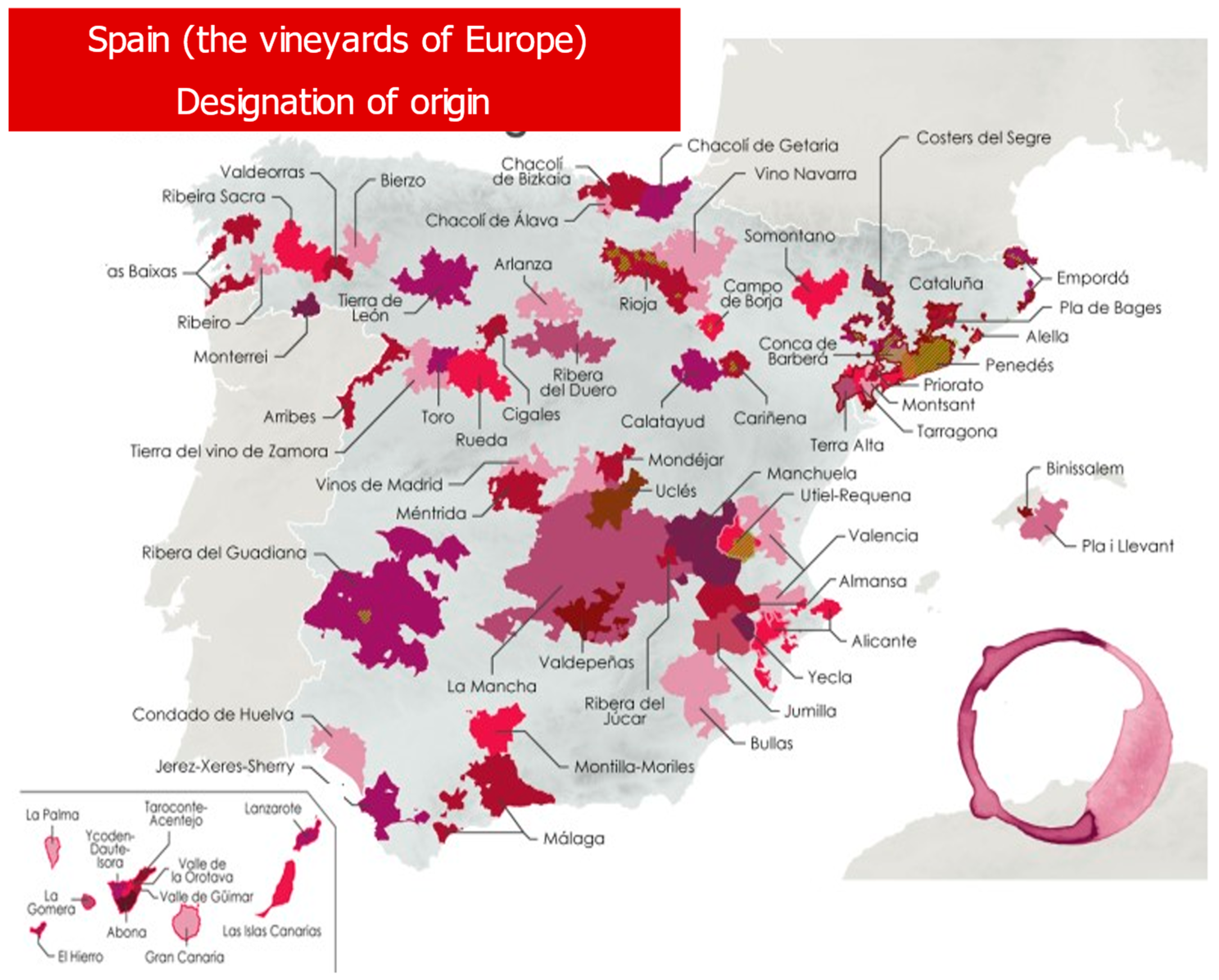

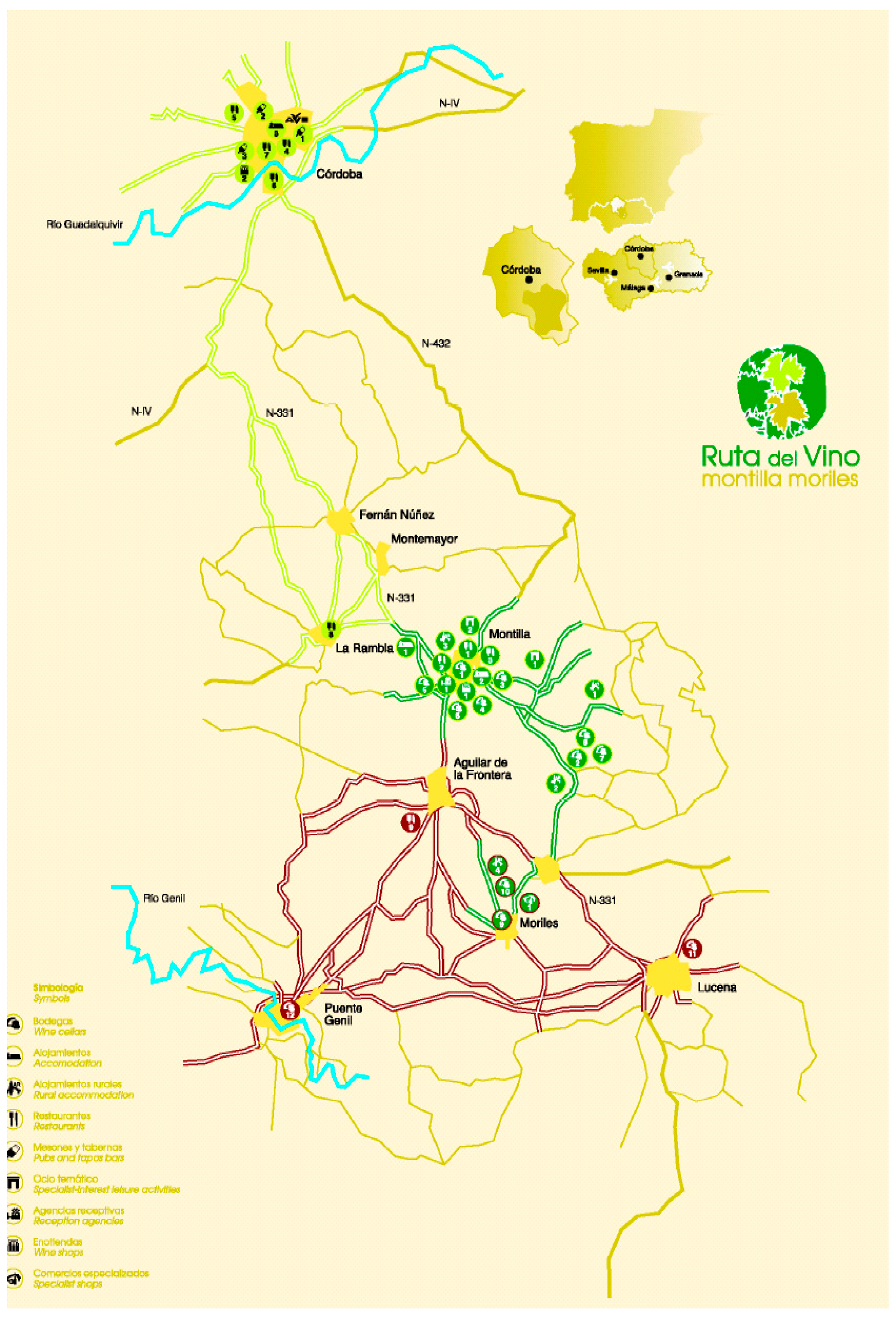

3. Enotourism: The Montilla-Moriles Route

- ⮚

- Wine lover. These individuals have a vast education in oenological aspects, and the main reason for their trip is to taste different types of wine, to buy bottles of wine and to learn in situ. They are also very interested in local gastronomy.

- ⮚

- The connoisseur. These individuals, although they do not have a vast education in oenological issues, know the world of wine relatively well. They usually have a university education, and the main reason for their trip is to put into practice what they have read in different specialized magazines.

- ⮚

- Wine interested. These individuals do not have technical training in oenological issues but are interested in the world of wine. Visiting wineries is not the main reason for their trip but rather as a complement to other activities.

- ⮚

- Wine novice. For different reasons (such as advertising along a route or wanting new experiences), these individuals visit wineries without having any knowledge in this field. The main reason for the trip is not associated with wine, but these individuals spend a few hours visiting wineries. The purchases they usually make are intended for private consumption or, in most cases, as gifts.

4. Materials and Methods

- ●

- Information on the number of monthly tourists who visit route Montilla-Moriles (from January 2015–February 2020).

- ●

- Data obtained through fieldwork and two different surveys (Table 3):

- ○

- The first survey was conducted during the months of February to May 2019 and included companies that are part of AVINTUR and the wineries that belong to the Montilla-Moriles Regulatory Council (in total, 85 businesses); the response rate was 46% (39 surveys received), with a margin of error of 4.7%. The objective of this survey was to determine the enotourism offerings in this area.

- ○

- The second survey, conducted during the months of February to December 2019, was applied to 500 people who visited this route. To determine the profile of wine tourists, a questionnaire consisting of 35 questions divided into four blocks of tourist consumers who visited the Montilla-Moriles wine route in 2019 was conducted. The first block of the questionnaire collected personal information (e.g., age, gender, educational level, marital status) The second block gathered information about the route taken (e.g., How did you learn about the gastronomic route? Did the route meet your expectations? What would you change? Did you travel expressly because of the gastronomic route?). The third block addressed the motivation for gastronomic tourism (e.g., Why did you choose a gastronomic route?). The fourth block collected information regarding value (e.g., services received on the route, price of the trip, hospitality and treatment received). The objective of this survey was to establish a profile of tourists who choose this type of tourism and to determine the motivation of such tourists, with the purpose of reinforcing and designing strategies that promote the development of wine tourism in the area.

| Offer Survey | Demand Survey | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Companies that are part of AVINTUR and the wineries that belong to the Montilla-Moriles Regulatory Council | Tourists of any gender over 18 years old who undertook/visited a route/PDO/PGI Montilla-Moriles |

| Sample size | 39 | 500 |

| Sampling error | ±4.7% | ±3.9% |

| Sampling System | Simple Random | Simple Random |

| Level of confidence | 95%; p = q = 0.5 | 95%; p = q = 0.5 |

| Date of fieldwork | February to May 2019 | February to December 2019 |

5. Results

5.1. Estimation of the Level of Tourist Satisfaction Relative to Their Expectations, Based on Their Socioeconomic Profile: A Logit Model

- -

- Gender of the respondent;

- -

- Age (over 18 years);

- -

- Professional activity: acp (professional), ace (employer with workers), acd (manager), acf (civil servant), actc (skilled worker), acta (self-employed worker), aces (student), acam (homemaker), or acj (retired);

- -

- Family income (thousands of euros/month): rf;

- -

- People with whom the trip was made: s (alone), p (partner), f (family) and a (friends);

- -

- Restaurant service: catering (one for good and zero for bad);

- -

- Number of times having previously visited the Montilla-Moriles geographic zone: nv;

- -

- Expenses incurred during the vacation: gr;

- -

- Recommend the geographical area as a tourist destination: re, dichotomous variable (one, yes; zero, no);

- -

- Days of vacation used for the type of tourism carried out: dv;

- -

- Number of wineries visited: b;

- -

- Opinion about lodging (dichotomous variable): oalo (one for good and zero for bad);

- -

- Complementary activities: acco (zero, bad; and one, good);

- -

- Price of the trip: price (zero, bad; one, good);

- -

- Hospitality (zero, bad; one, good);

- -

- Conservation of the environment: ce (zero, poor; one, good);

- -

- Accommodation (zero, poor; one, good);

- -

- Opinion on the information and signage along the route: is (zero, bad; one, good).

- ■

- The variable number of wineries visited positively influenced the degree of satisfaction with the trip because as the number of wineries visited increased, the degree of satisfaction was higher (B22 = 17.568).

- ■

- The age variable was also significant because when the age of the tourist increased, their level of satisfaction was higher (B2 = 12.253). In our opinion, this result could be related to the profile of wine tourists who visit this area, consistent with the previous classification made by Charters and Ali-Knight [89]. Depending on the profile of tourists, wineries sell different tourism products.

- ■

- Eighty-four percent of the people surveyed would recommend this tourist route, a result that, in our opinion, reflects the high degree of satisfaction that this destination provides to tourists (B20 = 14.572).

- ■

- Regarding the negative variables indicated by the travelers surveyed, the high price of the trip (B25 = −1.253) and the few complementary activities in the area (B24 = −4.983) were notable.

5.2. Estimation of the Demand for Enotourism in the Montilla-Moriles PDO: SARIMA Model

tϕ1 = 26.47281 * tθ1 = −101.7076 *

* Significant parameters for α = 0.05.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-L.; McAleer, M.; Ramos, V. A Charter for Sustainable Tourism after COVID-19; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basilea, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bakar, N.A.; Rosbi, S. Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2020, 7, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assaf, A.; Scuderi, R. COVID-19 and the recovery of the tourism industry. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lew, A.A.; Cheer, J.M.; Haywood, M.; Brouder, P.; Salazar, N.B. Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.G.D.; de la Torre, M.G.M.V.; Rojas, R.H. Analysis of the demand for gastronomic tourism in Andalusia (Spain). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Movimiento Turísticos en Fronteras. 2021. Available online: https://www.ine.es/daco/daco42/frontur/frontur0122.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Boksberger, P. Enhancing consumer value in wine tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.R.; Ramos, P.M.G.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Wine and wine tourism experience: A theoretical and conceptual review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoz, E.M.; Melewar, T.; Dennis, C. The Value of Region of Origin, Producer and Protected Designation of Origin Label for Visitors and Locals: The Case of Fontina Cheese in Italy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cava, J.A.; Millán, M.G.; Hernández, R. Analysis of the Tourism Demand for Iberian Ham Routes in Andalusia (Southern Spain): Tourist Profile. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wittwer, G.; Anderson, K. COVID-19’s impact on Australian wine markets and regions. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2021, 65, 822–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, G.; Morales, E.; Pérez, L.M. Turismo gastronómico, denominaciones de origen y desarrollo rural en Andalucía: Situación actual. Boletín De La Asoc. De Geógrafos Españoles 2014, 65, 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Morillo Moreno, M.C. Turismo y producto turístico. Evolución, conceptos, componentes y clasificación. Visión Gerenc. 2011, 10, 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Duarte, P. Destination image and loyalty development: The impact of tourists’ food experiences at gastronomic events. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernadez, R.R.; Cava, J.A. Turismo gastronómico y vino: Análisis de la oferta gastronómica y hospedaje en montilla y moriles. Rev. Int. De Tur. Empresa Y Territorio. RITUREM 2017, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, R.; Stone, M.J.; Wolf, E.; Pozzi, A. Wine travel in the United States: A profile of wine travellers and wine tours. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; de los Reyes, E.; Aramendia, G.Z. Rutas enológicas y desarrollo local. Presente y futuro en la provincia de Málaga. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Rodríguez García, J.; Vieira Rodríguez, Á. Revisión de la literatura científica sobre enoturismo en España. Cuad. De Tur. 2013, 32, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, M.V.; Cardona, J.R. Turismo y vino en la literatura académica: Breve revisión bibliográfica. Redmarka Rev. Académica De Mark. Apl. 2013, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Festa, G.; Shams, S.M.; Metallo, G.; Cuomoa, M.T. Opportunities and challenges in the contribution of wine routes to wine tourism in Italy—A stakeholders’ perspective of development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, D.; Metaxas, T. Sustainable Wine Tourism Development: Case Studies from the Greek Region of Peloponnese. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Sousa, B.; Valeri, M. Towards a framework for the global wine tourism system. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, P.; Chassagne, N. Post COVID-19 ecological and social reset: Moving away from capitalist growth models towards tourism as Buen Vivir. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masot, A.N.; Rodríguez, N.R. Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2021, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutierrez, P.; Cuesta, P. ustainable development and rural tourism in depopulated areas. Land 2021, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, H.T. El coronavirus reescribirá el turismo rural? Reinvención, adaptación y acción desde el contexto latinoamericano: Reinvenção, adaptação e ação no contexto latino-americano. Cenário Rev. Interdiscip. Em Tur. E Territ. 2020, 8, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso-Sánchez, D. El papel del turismo deportivo de naturaleza en el desarrollo rural. ROTUR Rev. De Ocio Y Tur. 2020, 14, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, P. Análisis de las empresas de turismo activo en España. ROTUR Rev. De Ocio Y Tur. 2020, 14, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acle-Mena, R.S.; Santos-Díaz, J.Y.; Herrera-López, B. La gastronomía tradicional como atractivo turístico de la ciudad de puebla, México. Rev. De Investig. Desarro. E Innovación 2020, 10, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández, R.R.D.H.; Dancausa, M.G. Turismo gastronómico La gastronomía tradicional de Córdoba (España). Estud. Y Perspect. En Tur. 2018, 27, 413–430. [Google Scholar]

- Castellón, L.M.; Fontecha, J.J. Gastronomy: A Source for the Development of Tourism and the Strengthening of Cultural Identity in Santander. Tur. Y Soc. 2018, 22, 167–193. [Google Scholar]

- Aramendia, G.Z.; De La Cruz, E.R.R.; Ruiz, E.C. The Sustainability of the Territory and Tourism Diversification: A Comparative Analysis of the Profile of the Traditional and the Oenologic Tourist Through the Future Route of Wine in Malaga. J. Bus. Econ. 2020, 11, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.K. Gastronomic tourism: A theoretical construct. In The Routledge Handbook of Gastronomic Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josphine, J. A Critical Review of Gastronomic Tourism Development in Kenya. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Okumus, B. Food tourism research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S.; Suntikul, W.; Agyeiwaah, E. Determining the attributes of gastronomic tourism experience: Applying impact-range performance and asymmetry analyses. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Horvat, I. Differentiation of Commercial PDO Wines Produced in Istria (Croatia) According to Variety and Harvest Year Based on HS-SPME-GC/MS Volatile Aroma Compound Profiling. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 55, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, M.G.; Dancausa, M.G. El desarrollo turístico de zonas rurales en España a partir de la creación de rutas del vino: Un análisis DAFO. Teoría Y Prax. 2012, 12, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Cárdenas-García, P.J. Analyzing the Bidirectional Relationship between Tourism Growth and Economic Development. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleví, G.; Nicolas-Sans, R.; Álvarez, J.; Villoro, J. PDO Certification: A Brand Identity for Wine Tourism. Geographicalia 2020, 72, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleví, G.; Miró, A.P. Des outils pour la défense du paysage vitivinicole. Le cas du Penedès (Espagne). Sud-Ouest Européen 2018, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.F.; Triana Valiente, M.F. Las rutas gastronómicas en el departamento del Meta. Una propuesta de sustentabilidad turística. Tur. Y Soc. 2019, 25, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y alimentación. Datos de las Denominaciones de Origen Protegidas (D.O.P.), Indicaciones Geográficas Protegidas (I.G.P.) y Especialidades Tradicionales Garantizadas (E.T.G.) de Productos Agroalimentarios; Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- Romero, C.; García, P.; Medina, E.; Brenes, M. The PDO and PGI Table Olives of Spain. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2019, 121, 1800136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanco, M.; Riveros, H. Las rutas alimentarias una herramienta para valorizar productos de las agroindustrias rurales. El caso de la ruta del queso Turrialba, Costa Rica. Perspectivas Rurales 2005, 17–18, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Developing cheese tourism: A local-based perspective from Valle de Roncal (Navarra, Spain). J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.L.; Fernão-Pires, M.J.; Bianchi-De-Aguiar, F. Portuguese vines and wines: Heritage, quality symbol, tourism asset. Cienc. E Tec. Vitivinic. 2018, 33, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, E. Turismo Rural: Nueva Ruralidad y Empleo Rural no Agrícola; CINTERFOR/OIT: Montivedeo, Uruguay, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santeramo, F.G.; Seccia, A.; Nardone, G. The synergies of the Tourism and Wine Italian sectors. Wine Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J. The Wine Tourism Experience in New Zealand: An Investigation of Chinese Visitors’ Interest and Engagement. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.F.; Singh, N.; Hsiung, Y. Determining the Critical Success Factors of the Wine Tourism Region of Napa from a Supply Perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, D.; Bell, A. Chilean wines: A successful image. Int. J. Wine Mark. 2002, 14, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Analysis of Hospitality, Leisure, and Tourism Studies in Chile. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, B.E.; Rotarou, E.S. Challenges and opportunities for the sustainable development of the wine tourism sector in Chile. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szivas, E. The Development of Wine Tourism in Hungary. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1999, 11, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M. Wine Tourism in New Zealand—Maybe The Industry Has Got It Right. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1998, 10, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, T.; Hall, C.M.; Castka, P. New Zealand Winegrowers Attitudes and Behaviours towards Wine Tourism and Sustainable Winegrowing. Sustainability 2018, 10, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Fountain, J. Characterising resilience in the wine industry: Insights and evidence from Marlborough, New Zealand. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 94, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, J.M.; Crick, D.; Tebbett, N. Competitor orientation and value co-creation in sustaining rural New Zealand wine producers. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 73, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J.; Thompson, C. Wine tourist’s perception of winescape in Central Otago, New Zealand. In Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J. South African wine routes: Some perspectives on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booyens, I. Tourism innovation in the Western Cape, South Africa: Evidence from wine tourism. In New Directions in South African Tourism Geographies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S.L.A.; Hunter, C.A. Wine tourism development in South Africa: A geographical analysis. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 676–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovi, M.; Pucciarelli, F. Social media marketing in wine tourism: Winery owners’ perceptions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, F.; Vallerani, F. A Countryside to Sip: Venice Inland and the Prosecco’s Uneasy Relationship with Wine Tourism and Rural Exploitation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez, M.; Pratt, M.A.; Molina, A. Wine tourism research: A systematic review of 20 vintages from 1995 to 2014. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2211–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, T.V.; Kirova, V. Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, C. El Enoturismo En La Ribera Del Duero Y Napa Valley: Análisis Comparative; Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Hsiung, Y. Exploring critical success factors for Napa’s wine tourism industry from a demand perspective. Anatolia 2016, 27, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, A.M. Napa Valley, California: A model of wine region development. In Wine Tourism around the World; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, C.; Azevedo, A. Generation x and y expectations about wine tourism experiences: Douro (portugal) versus Napa valley (USA). Tour. Manag. Stud. 2011, 1, 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Nave, A.; Laurett, R.; do Paço, A. Relation between antecedents, barriers and consequences of sustainable practices in the wine tourism sector. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, J.C.P.; Fernández, G.A.M.; Guzmán, T.L.-G. Motivación y satisfacción turística en los festivales del vino: XXXI ed. cata del vino Montilla-Moriles, España. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2015, 11, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.; Molina, A. Wine Tourism in Spain: Denomination of Origin Effects on Brand Equity. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, M. Competitividad de la Industria de Vinos de Calidad Españoles: Un Análisis de Las Exportaciones de Las Denominaciones de Origen Protegidas de Vinos de España; Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, D.C. Touristic Development of a Viticultural Region of Spain. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1992, 4, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Peris, E.; Roig, B.; Clemente, J. El cooperativismo agrario de interior y su competitividad: El caso del cooperativismo vitivinícola en la comunidad valenciana. In Desarrollo Rural Y Economía Social: Resúmenes De Conferencias Y Comunicaciones; Universidad Católica de Avila: Avila, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Melián, A.; Millán, M.G. El cooperativismo vitivinícola en España. Un estudio exploratorio en la Denominación de Origen de Alicante. REVESCO Rev. De Estud. Coop. 2007, 93, 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, J.S.; Roig, B.; Valencia, S.; Rabadan, M.T.; Martinez, C. Actitud hacia la gastronomía local de los turistas: Dimensiones y segmentación de mercado. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2008, 6, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armesto, X.A.; Gómez, B. Productos agroalimenta-rios de calidad, turismo y desarrollo local: El caso del Priorat. Cuad. Geográficos 2004, 34, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes García, F.; Veroz Herradón, R. Plan Estratégico De La Denominación De Origen Montilla-Moriles; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M.G.; Morales, E.; Castro, M.S. Turismo del vino: Una aproximación a las buenas prácticas. TURyDES 2012, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, G.; Melián, A. Rutas turísticas enológicas y desarrollo rural: El caso estudio de la denominación de origen Montilla-Moriles en la provincia de Córdoba. Pap. De Geogr. 2008, 47–48, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Elías, L.V. El Turismo Del Vino: Otra Experiencia Del Ocio; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cristófol, F.; Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G. Transmission of Place Branding Values through Experiential Events: Wine BC Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E. Key Elements for the Design of a Wine Route. The Case of La Axarquía in Málaga (Spain). Sustainability. 2020, 12, 9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.L. American Winescapes: The Cultural Landscapes of America’s Wine Country; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Who is the wine tourist? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nella, A.; Christou, E. Market segmentation for wine tourism: Identifying sub-groups of winery visitors. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 29, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio turístico rutas del vino de España. Informe de Visitantes a Bodegas y Museos Del Vino; ACEVIN—Rutas del vino de España: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina Ureña, M.D. El Valor Del Enoturismo En El Desempeño Organizacional De Las Bodegas Españolas Y El E-Wom; Universitat Politècnica de València: València, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, A.G.; Ojeda, A.Á.R.; Torres, S.H. El cultivo del viñedo como recurso turístico cultural: El caso de la Geria (Lanzarote. Islas Canarias, España). Pap. De Geogr. 2015, 61, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caridad, J.M. Econometria: Modelos Econometricos y Series Temporales: Con los Paquetes UTSP y TSP; Reverte: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D.N. Econometria; Mc. Graw Hill: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sundbo, J.; Dixit, S.K. Conceptualizations of tourism experience. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Experience Management and Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.W.; Kelly, J. Cultural wine tourists: Product development considerations for British Columbia’s resident wine tourism market. Int. J. Wine Mark. 2001, 13, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Wine and food events: Experiences and impacts. In Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Pérez-Gálvez, J.C.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.A. A Quality-of-Life Perspective of Tourists in Traditional Wine Festivals: The Case of the Wine-Tasting Festival in Córdoba, Spain. In Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Winfree, J.; McIntosh, C.; Nadreau, T. An economic model of wineries and enotourism. Wine Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Vieira, Á.; López-Guzmán, T. Segmentación del perfil de enoturista en la ruta del vino del marco de Jerez-Xérès-Sherry. TURyDES 2012, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Gil, Á. Rutas de la Rioja: Nuevos itinerarios, industria de viajeros y desarollo; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, S.; Remondes, J.; Costa, A.P. Estudo do perfil e motivações do enoturista: O caso da quinta da Gaivosa. Cult. Rev. De Cult. E Tur. 2021, 15, 3. [Google Scholar]

| Agri-Food Products | PDO | PGI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | Andalusia | Spain | Andalusia | |

| Fresh meat (and offal) | - | - | 22 | - |

| Meat products | 5 | 1 | 11 | 2 |

| Cheeses | 27 | - | 2 | - |

| Other products of animal origin (honey | 3 | 1 | 4 | - |

| Oils and fats (32 oils and 2 butters) | 34 | 13 | 3 | 1 |

| Fresh and processed fruit, vegetables and grains | 1 | - | 4 | 4 |

| Other products (saffron, paprika, chufa (nutsedge), hazelnut, vinegar, cider) | 9 | 3 | - | - |

| Bakery, confectionary, pastry and biscuit products | - | - | 16 | 4 |

| Suckling pig (Cochinilla) | 1 | - | - | - |

| Total PDOs and PGIs for agri-food products | 106 | 22 | 98 | 13 |

| Wine with a designation of origin (DO) | 73 | 6 | - | - |

| Wine with a guaranteed designation of origin (DOCa) | 2 | - | - | - |

| Wine of quality with a geographical indication (VC) | 10 | 2 | - | - |

| Vinos de Pago (VP) = Quality wines from a single estate that fall outside the DO | 11 | - | - | - |

| Wine with a geographical indication (GI) | - | - | 42 | 16 |

| Aromatized wine | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Total PDOs and PGIs for WINE | 96 | 8 | 43 | 17 |

| Spirits with PGIs | - | - | 19 | 1 |

| Total PDOs and PGIs | 202 | 30 | 160 | 31 |

| Country | PDO | PGI |

|---|---|---|

| Greece | 33 | 45 |

| Spain | 96 | 43 |

| Italy | 420 | 127 |

| Netherland | 9 | 12 |

| Portugal | 36 | 17 |

| France | 478 | 76 |

| Belgium | 8 | 2 |

| Bulgaria | 54 | 1 |

| Czechia | 11 | 2 |

| Denmark | 1 | 4 |

| Germany | 19 | 26 |

| Cyprus | 7 | 4 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | |

| Hungary | 49 | 7 |

| Malt | 2 | 1 |

| Austria | 34 | 3 |

| Romania | 42 | 14 |

| Slovenia | 14 | 3 |

| Slovakia | 8 | 1 |

| Total | 1322 | 388 |

| Dependent Variable: Satisf | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: ML—Binary Logit (Quadratic Hill Climbing) | ||||

| Variable | Estimated Coefficient | Standard Deviation | Z | Prob |

| Intercept | B0 = 2.325 | 0.103 | 22.572 | 0.010 |

| Gender | B1 = 0.631 | 0.002 | 315.500 | 0 |

| Age | B2 = 12.253 | 2.251 | 5.443 | <0.0002 |

| Professional, acp | B3 = 9.256 | 1.425 | 6.495 | <0.0002 |

| Entrepreneur, ace | B4 = 0.042 | 0.001 | 42.000 | 0 |

| Management, acd | B5 = 0.035 | 0.002 | 17.500 | 0 |

| Official, acf | B6 = 13.564 | 1.561 | 8.689 | <0.0002 |

| Skilled worker, actc | B7 = 17.891 | 3.458 | 5.174 | <0.0002 |

| Self-employed, acta | B8 = 10.584 | 2.231 | 4.744 | <0.0002 |

| Student, aces | B9 = −0.058 | 0.001 | −58.000 | 0 |

| Homemaker, acam | B10 = 9.856 | 2.521 | 3.909 | <0.0002 |

| Retired, acj | B11 = 8.642 | 1.658 | 5.212 | <0.0002 |

| Family income, rf | B12 = 15.324 | 2.567 | 5.969 | <0.0002 |

| Traveling alone, s | B13 = −0.567 | 1.261 | −0.449 | 0.3264 * |

| Traveling as a couple, p | B14 = 7.368 | 3.457 | 2.131 | 0.0166 |

| Traveling with family, f | B15 = 14.658 | 1.578 | 9.289 | <0.0002 |

| Catering | B16 = 4.328 | 0.679 | 6.374 | <0.0002 |

| Traveling with friends, a | B17 = 6.745 | 2.012 | 3.352 | <0.0002 |

| Number of visits, nv | B18 = 2.561 | 0.123 | 20.821 | 0 |

| Expenditures, gr | B19 = 1.568 | 0.111 | 14.126 | 0 |

| Would recommend trip, re | B20 = 14.572 | 2.877 | 5.065 | <0.0002 |

| Vacation days, dv | B21 = 0.045 | 0.001 | 45.000 | 0 |

| Wineries visited, b | B22 = 17.568 | 3.684 | 4.768 | <0.0002 |

| Lodging opinion, oalo | B23 = 0.536 | 0.014 | 38.285 | 0 |

| Complementary activities, acco | B24 = −4.983 | 1.021 | −4.881 | <0.0002 |

| Trip price, price | B25 = −1.253 | 0.014 | 89.500 | 0 |

| Hospitality | B26 = 3.762 | 0.985 | 3.819 | <0.0002 |

| Environmental conservation, ce | B27 = 1.236 | 0.021 | 58.857 | 0 |

| Information and signage, is | B28 = 0.023 | 0.002 | 11.501 | <0.0002 |

| Dependent Variable: D(ENOTOURIST1,12) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: ML ARCH (Marquardt) Normal Distribution | ||||

| GARCH = C(3) + C(4)*RESID(−1)2 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | z-Statistic | Prob. |

| AR(1) | −1.078216 | 0.040729 | −26.47281 | 0.0000 |

| MA(1) | −0.997914 | 0.009812 | −101.7076 | 0.0000 |

| Variance Equation | ||||

| C | 14419635 | 5663686. | 2.545981 | 0.0109 |

| RESID(−1)2 | −2.393621 | 1.099372 | −2.177263 | 0.0295 |

| R-squared | 0.910115 | Mean dependent var | −77.28674 | |

| Month | Year 2019 | Year 2022 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 636 | 735 | 99 |

| February | 779 | 824 | 45 |

| March | 1258 | 1328 | 70 |

| April | 2446 | 2566 | 120 |

| May | 3725 | 3846 | 121 |

| June | 2538 | 2624 | 86 |

| July | 2601 | 2700 | 99 |

| August | 2589 | 2695 | 106 |

| September | 4701 | 4928 | 227 |

| October | 3325 | 3432 | 107 |

| November | 2708 | 2652 | −56 |

| December | 3824 | 3924 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cava Jimenez, J.A.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G.; Dancausa Millán, M.G. Enotourism in Southern Spain: The Montilla-Moriles PDO. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063393

Cava Jimenez JA, Millán Vázquez de la Torre MG, Dancausa Millán MG. Enotourism in Southern Spain: The Montilla-Moriles PDO. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063393

Chicago/Turabian StyleCava Jimenez, Jose Antonio, Mª Genoveva Millán Vázquez de la Torre, and Mª Genoveva Dancausa Millán. 2022. "Enotourism in Southern Spain: The Montilla-Moriles PDO" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063393