The Effects of Types of Service Providers on Experience Economy, Brand Attitude, and Brand Loyalty in the Restaurant Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Robots in the Hospitality Industry

2.2. The Experience Economy

2.3. Effect of Experience Economy on Brand Attitude

2.4. Effect of Brand Attitude on Brand Loyalty

2.5. Difference Analysis according to the Type of Service Providers

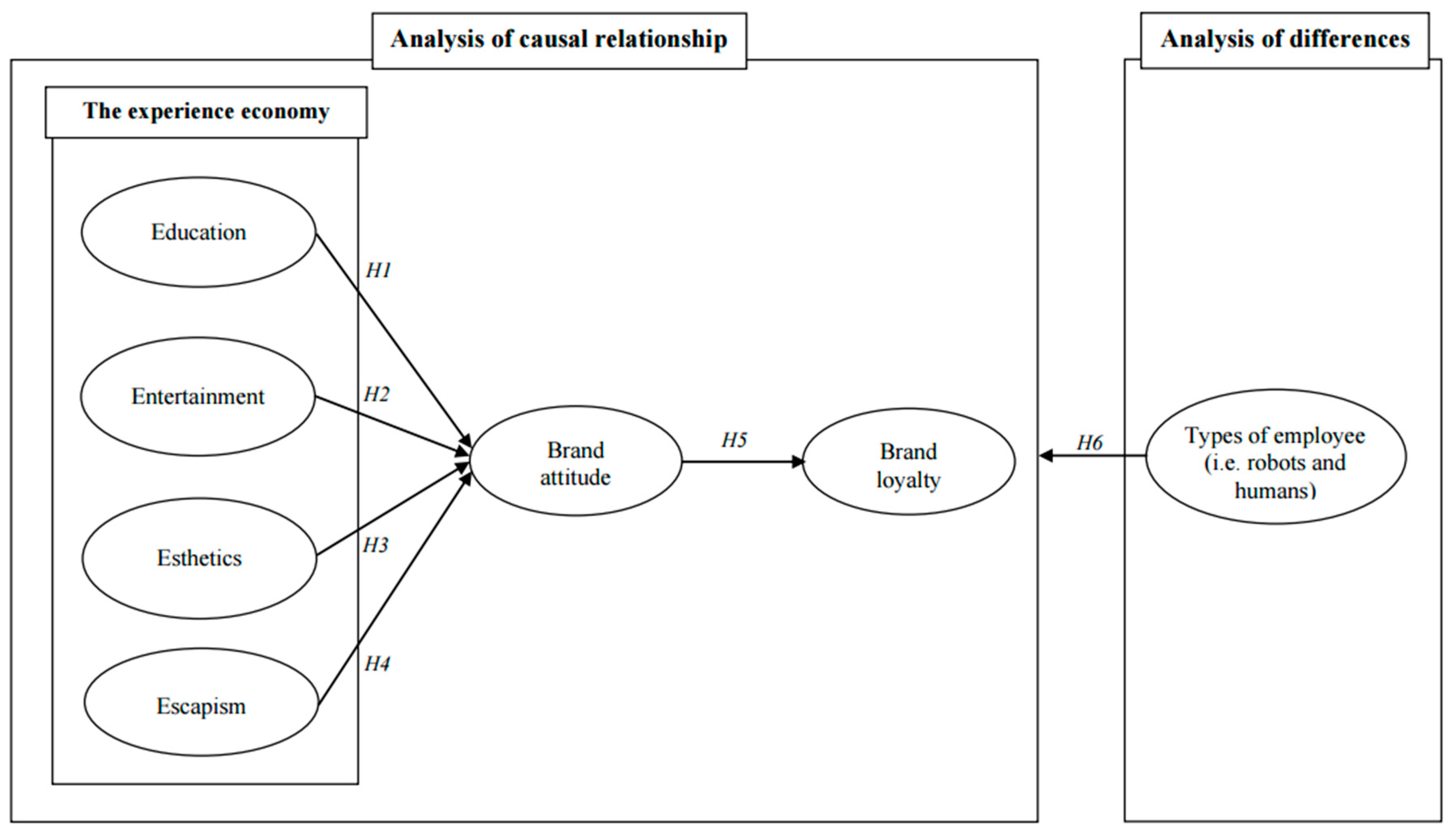

2.6. Proposed Conceptual Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement Items

3.2. Data Collection

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Profile of the Respondents

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

4.4. Results of t-Tests

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Two Types of Restaurants

References

- Jang, H.W.; Lee, S.B. Serving robots: Management and applications for restaurant business sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.H.; Lee, J.H. The Emergence of Service Robots at Restaurants: Integrating Trust, Perceived Risk, and Satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobeiri, S.; Mazaheri, E.; Laroche, M. Improving customer website involvement through experiential marketing. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Oh, H.; Park, J. Measuring the experience economy of film festival participants. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2010, 10, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.J. Human baristas and robot baristas: How does brand experience affect brand satisfaction, brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K.; Fan, A.; Her, E.; Liu, Y.; Almanza, B.; Leitch, S. Robot vs human: Expectations, performances and gaps in off-premise restaurant service modes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3996–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.S. Customers’ intention to use robot-serviced restaurants in Korea: Relationship of coolness and MCI factors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2947–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejos, N. Introducing Connie, Hilton’s New Robot Concierge. USA Today 2016. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/roadwarriorvoices/2016/03/09/introducing-connie-hiltons-new-robot-concierge/81525924/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Alexis, P. R-Tourism: Introducing the Potential Impact of Robotics and Service Automation in Tourism. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Ser. Econ. Sci. 2017, 17, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Chuah, S.H.W.; Aw, E.C.X.; Cheng, C.F. A silver lining in the COVID-19 cloud: Examining customers’ value perceptions, willingness to use and pay more for robotic restaurants. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.K.; Lee, J.; Cha, S.S. Senior Consumer Motivations and Perceived Value of Robot Service Restaurants in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Arcodia, C.; Novais, M.A.; Kralj, A. Producing authenticity in restaurant experiences: Interrelationships between the consumer, the provider, and the experience. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. The antecedents and consequences of well-being perception: An application of the experience economy to golf tournament tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. Search for a Word. Retrieved from Dictionary by Merriam-Webster: America’s Most-Trusted Online Dictionary. 2022. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Hosany, S.; Witham, M. Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S.S. The effect of environmental perceptions on behavioral intentions through emotions: The case of upscale restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2007, 31, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. Perceived firm innovativeness in cruise travelers’ experience and perceived luxury value: The moderating effect of advertising effectiveness. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, S101–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chernatony, L.; Dall’Olmo Riley, F. Defining a “brand”: Beyond the literature with experts’ interpretations. J. Mark. Manag. 1998, 14, 417–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Harcourt Brace, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Corfman, K.P. Quality and value in the consumption experience: Phaedrus rides again. Perceived Qual. 1985, 31, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Ok, C. The antecedents and consequence of consumer attitudes toward restaurant brands: A comparative study between casual and fine dining restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Jaworski, B.J.; MacInnis, D.J. Strategic brand concept-image management. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; MacInnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Engen, M. Pine and Gilmore’s concept of experience economy and its dimensions: An empirical examination in tourism. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 12, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeong, E.; Qu, K. Exploring theme park visitors’ experience on satisfaction and revisit intention: A Utilization of experience economy model. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 474–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.T.; Shoemaker, S. Loyalty: A strategic commitment. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1998, 39, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.F.; Sasser, W.E. Zero defeofions: Quoliiy comes to services. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, A.H.; Park, H.Y. The Effect of Airline’s Professional Models on Brand Loyalty: Focusing on Mediating Effect of Brand Attitude. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.N.; Hu, C.; Lin, M.C.; Tsai, T.I.; Xiao, Q. Brand knowledge and non-financial brand performance in the green restaurants: Mediating effect of brand attitude. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Hwang, J. Application of consumer innovativeness to the context of robotic restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 33, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, E.; Vanscoy, J.; Feraco, T.A.; Stilwell, I.; Bushe, B. A Study of a Traffic Controlling Robot for Safer Work Zones; Worcester Polytechnic Institute: Worcester, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hankookilbo. COVID-19 Era, ‘Serving and Cooking Robot’... Was It just Because It Was Convenient and Cheap? Available online: https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/A2021091714560003008 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Hwang, J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, I. Robotic Restaurant Marketing Strategies in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Focusing on Perceived Innovativeness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, A.H.; Trimi, S. Impacts of service robots on service quality. Serv. Bus. 2020, 14, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.J. The antecedents and consequences of memorable brand experience: Human baristas versus robot baristas. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. First-class airline travelers’ tendency to seek uniqueness: How does it influence their purchase of expensive tickets? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Park, S. An exploratory study of how casino dealer communication styles lead to player satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gursoy, D.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, S. Impact of anthropomorphic features of artificially intelligent service robots on consumer acceptance: Moderating role of sense of humor. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3883–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauppé, A.; Mutlu, B. The social impact of a robot co-worker in industrial settings. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 3613–3622. [Google Scholar]

- Jing Daily. Is K-Beauty’s Reign Coming to a Close? Available online: https://jingdaily.com/amorepacific-etude-house-kbeauty-china/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Tsaur, S.H.; Tang, W.H. The burden of esthetic labor on front-line employees in hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. A study on the application of the experience economy to luxury cruise passengers. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | A Restaurant Where Robots Provide Services (n = 296) | A Restaurant Where Humans Provide Services (n = 294) | Merging Two Data (n = 590) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 124 (41.9%) | 147 (50.0%) | 271 (45.9%) |

| Female | 172 (58.1%) | 147 (50.0%) | 319 (54.1%) |

| Age | |||

| 20s | 63 (21.3%) | 70 (23.8%) | 133 (22.5%) |

| 30s | 107 (36.1%) | 97 (33.0%) | 204 (34.6%) |

| 40s | 79 (26.7%) | 70 (23.8%) | 149 (25.3%) |

| 50s | 47 (15.9%) | 57 (19.4%) | 104 (17.6%) |

| Education level | |||

| Less than high school diploma | 9 (3.0%) | 20 (6.8%) | 29 (4.9%) |

| Associate’s degree | 25 (8.4%) | 36 (12.2%) | 61 (10.3%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 245 (82.8%) | 187 (63.6%) | 423 (73.2%) |

| Graduate degree | 17 (5.7%) | 17.3 (51%) | 68 (11.5%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 131 (44.3%) | 134 (45.6%) | 265 (44.9%) |

| Married | 164 (55.4%) | 159 (54.1%) | 323 (54.7%) |

| Others | 1 (.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| Income level | |||

| USD 6001 and over | 76 (25.7%) | 60 (20.4%) | 136 (23.1%) |

| USD 5001–6000 | 67 (22.6%) | 47 (16.0%) | 114 (19.3%) |

| USD 4001–5000 | 84 (28.4%) | 47 (16.0%) | 131 (22.2%) |

| USD 3001–4000 | 46 (15.5%) | 77 (26.2%) | 123 (20.8%) |

| USD 2001–3000 | 13 (4.4%) | 41 (13.9%) | 54 (9.2%) |

| Under USD 2000 | 10 (3.4%) | 22 (7.5%) | 32 (5.4%) |

| Construct and Scale Item | Standardized Loading a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | RP | MTD | |

| Experience economy | |||

| Education | |||

| This robotic server made me more knowledgeable. | 0.855 | 0.896 | 0.898 |

| This robotic server stimulated my curiosity to learn new things. | 0.912 | 0.944 | 0.946 |

| This robotic server provided a real learning experience. | 0.780 | 0.883 | 0.871 |

| Entertainment | |||

| This robotic server kept me amused. | 0.903 | 0.902 | 0.902 |

| This robotic server was entertaining. | 0.891 | 0.901 | 0.898 |

| This robotic server was fun. | 0.943 | 0.895 | 0.917 |

| Esthetics | |||

| The appearance of the robotic server was good. | 0.865 | 0.883 | 0.869 |

| The robot server looked good. | 0.895 | 0.921 | 0.902 |

| The robotic server was attractive. | 0.929 | 0.834 | 0.884 |

| Escapism | |||

| I felt I was in a different world while using this robot server. | 0.900 | 0.847 | 0.884 |

| I completely escaped from my daily routine while the robotic server offered me its services at this restaurant. | 0.787 | 0.884 | 0.849 |

| I felt like I was in a different place while using this robot server at this restaurant. | 0.906 | 0.891 | 0.906 |

| Brand attitude | |||

| Unfavorable–Favorable | 0.861 | 0.830 | 0.881 |

| Negative–Positive | 0.832 | 0.917 | 0.898 |

| Bad–Good | 0.911 | 0.923 | 0.927 |

| Brand loyalty | |||

| I say positive things about this restaurant brand to others. | 0.895 | 0.899 | 0.900 |

| I would like to use this restaurant brand more often. | 0.873 | 0.855 | 0.866 |

| I would like to use this restaurant brand in the future. | 0.909 | 0.873 | 0.882 |

| Mean (Std Dev.) | AVE | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Education | 5.31 (1.05) 4.30 (1.27) 4.81 (1.27) | 0.724 0.825 0.820 | 0.887 0.934 0.932 | 0.731 a 0.459 0.563 | 0.654 0.382 0.489 | 0.766 0.611 0.696 | 0.528 0.313 0.409 | 0.675 0.523 0.583 |

| (2) Entertainment | 5.70 (0.82) 5.46 (0.90) 5.58 (0.87) | 0.833 0.809 0.821 | 0.534 b 0.211 0.317 | 0.937 0.927 0.933 | 0.768 0.804 0.794 | 0.767 0.690 0.718 | 0.742 0.430 0.534 | 0.812 0.830 0.827 |

| (3) Esthetics | 5.65 (0.90) 5.48 (0.90) 5.56 (0.90) | 0.804 0.774 0.783 | 0.428 0.146 0.239 | 0.590 0.646 0.630 | 0.925 0.911 0.783 | 0.798 0.704 0.740 | 0.650 0.423 0.499 | 0.720 0.721 0.730 |

| (4) Escapism | 5.57 (0.85) 5.10 (1.03) 5.34 (0.97) | 0.750 0.764 0.774 | 0.587 0.373 0.484 | 0.588 0.476 0.516 | 0.637 0.496 0.548 | 0.900 0.907 0.774 | 0.688 0.449 0.544 | 0.750 0.672 0.706 |

| (5) Brand attitude | 5.87 (0.74) 5.69 (1.05) 5.78 (0.91) | 0.754 0.794 0.814 | 0.279 0.098 0.167 | 0.551 0.185 0.285 | 0.423 0.179 0.249 | 0.473 0.202 0.296 | 0.902 0.920 0.814 | 0.733 0.433 0.531 |

| (6) Brand loyalty | 5.62 (0.82) 5.35 (1.00) 5.49 (0.92) | 0.796 0.767 0.779 | 0.456 0.274 0.340 | 0.659 0.689 0.684 | 0.518 0.520 0.533 | 0.563 0.452 0.498 | 0.537 0.187 0.282 | 0.921 0.908 0.779 |

| Types of Service Providers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Restaurant Where Robots Provide Services | A Restaurant Where Humans Provide Services | t-Value | p-Value | ||

| Experience economy | Education | 5.31 | 4.30 | 10.516 | 0.000 *** |

| Entertainment | 5.70 | 5.46 | 3.428 | 0.001 ** | |

| Esthetics | 5.65 | 5.48 | 2.268 | 0.024 * | |

| Escapism | 5.57 | 5.10 | 6.037 | 0.000 *** | |

| A restaurant where robots provide services | A restaurant where humans provide services | t-value | p-value | ||

| Attitude | 5.87 | 5.69 | 2.433 | 0.015 * | |

| A restaurant where robots provide services | A restaurant where humans provide services | t-value | p-value | ||

| Brand loyalty | 5.62 | 5.35 | 3.564 | 0.000 *** | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, J.; Abbas, J.; Joo, K.; Choo, S.-W.; Hyun, S.S. The Effects of Types of Service Providers on Experience Economy, Brand Attitude, and Brand Loyalty in the Restaurant Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063430

Hwang J, Abbas J, Joo K, Choo S-W, Hyun SS. The Effects of Types of Service Providers on Experience Economy, Brand Attitude, and Brand Loyalty in the Restaurant Industry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063430

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Jinsoo, Jawad Abbas, Kyuhyeon Joo, Seung-Woo Choo, and Sunghyup Sean Hyun. 2022. "The Effects of Types of Service Providers on Experience Economy, Brand Attitude, and Brand Loyalty in the Restaurant Industry" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063430