Validation of a Questionnaire of Food Education Content on School Catering Websites in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

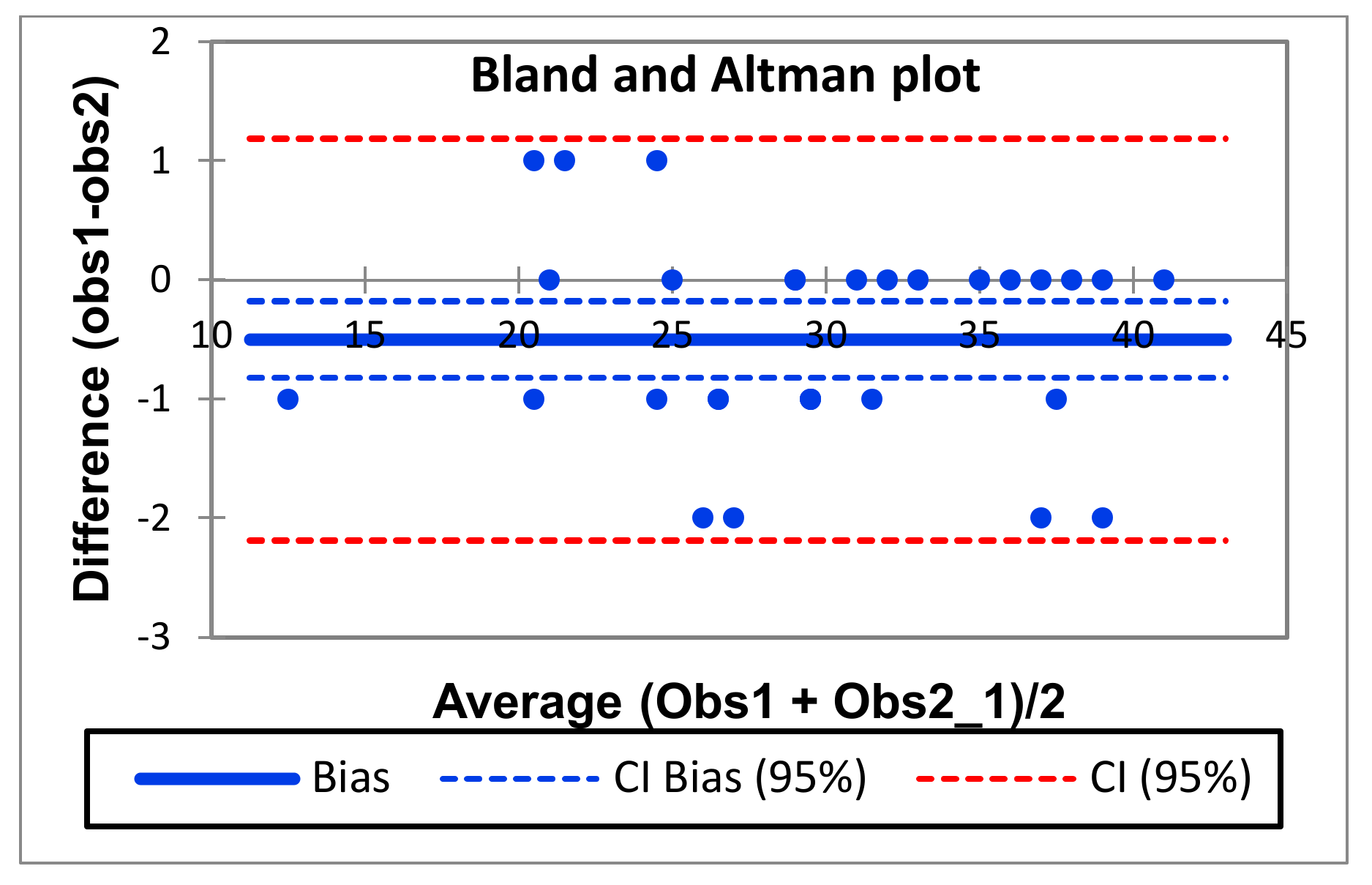

3.2. Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manson, A.; Johnson, B.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Sutherland, R.; Golley, R. The food and nutrient intake of 5- to 12 year-old Australian children during school hours: A secondary análisis of the 2011–2012 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5985–5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiquer, I.; Haroa, A.; Cabrera-Vique, C.; Muñoz-Hoyos, A.; Galdóc, G. Evaluación nutricional de los menús servidos en las escuelas infantiles municipales de Granada. An. Pediatr. 2016, 85, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durá, T.; Sánchez-Valverde, F. Obesidad infantil: ¿Un problema de educación individual, familiar o social? Acta Pediatr. Esp. 2005, 63, 204–207. Available online: https://studylib.es/doc/4484868/obesidad-infantil--%C2%BFun-problema-de-educaci%C3%B3n-individual-- (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Macias, M.A.I.; Gordillo, S.L.G.; Camacho, R.E.J. Hábitos alimentarios de niños en edad escolar y el papel de la educación para la salud. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2012, 39, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, S.D.; Cuadrado, C.; Rodríguez, M.; Quintanilla, L.; Ávila, J.M.; Moreiras, O. Planificación nutricional de los menús escolares para los centros públicos de la Comunidad de Madrid. Nutr. Hosp. 2006, 21, 667–672. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112006000900006&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 24 October 2021). [PubMed]

- Caballero-Treviño, M.C. Papel del Comedor Escolar en la Dieta de la Población Infantil de Villanueva de la Cañada. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2010. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/11968/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Quiles-Izquierdo, J.; Zubeldia-Lauzurica, L.; Álvarez-Pitti, J.; Blesa-Baviera, L.; Codoñer-Franch, P.; Crespo-Escobar, P.; Girba-Rovira, I.; Guadalupe-Fernádez, V.; Redondo-Gallego, M.J.; Serrano-Montero, A.; et al. Guía para los Menús en Comedores Escolares 2018; Conselleria de Sanidad Universal y Salud Pública: Valencia, Spain; Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 2018; Available online: http://www.san.gva.es/documents/151311/7497836/Guia+Menu+Comedores+Escolares+GVA+2018.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Peñalvo, J.L.; Oliva, B.; Sotos-Prieta, M.; Uzhova, I.; Moreno-Franco, B.; León-Latre, M.; Ordovás, J.M. La mayor adherencia a un patrón de dieta mediterránea se asocia a una mejora del perfil lipídico plasmático: La cohorte del Aragon Health Workers Study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2015, 68, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Muniz, F.J. La obesidad un grave problema de Salud Pública. An. Real Acad. Nac. Farm. 2016, 82, 6–26. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6658272 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Díaz, J. Childhood obesity: Prevention or treatment? An. Pediatr. 2017, 86, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibiloni, M.M.; Fernández-Blanco, J.; Pujol-Plana, N.; Martín-Galindo, N.; Fernández-Vallejo, M.M.; Roca-Domingo, M.; Chamorro-Medina, J.; Tur, J.A. Mejora de la calidad de la dieta y del estado nutricional en población infantil mediante un programa innovador de educación nutricional: INFADIMED. Gac. Sanit. 2017, 31, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Moráis, A.B.; Pérez, J.D. Valoración nutricional en Atención Primaria ¿es posible? Rev. Pediatr. Aten. Primaria 2011, 13, 255–269. Available online: https://pap.es/articulo/11492/valoracion-nutricional-en-atencion-primaria-es-posible (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Martínez, M.I.; Hernández, M.D.; Ojeda, M.; Mena, R.; Alegre, A.; Alfonso, J.L. Desarrollo de un programa de educación nutricional y valoración del cambio de hábitos alimentarios saludables en una población de estudiantes de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria. Nutr. Hosp. 2009, 24, 504–510. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112009000400017&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 17 October 2021). [PubMed]

- Gascón, L. Educación nutricional en la escuela como prevención de la obesidad infantil y de los TCA. In Libro de Ponencias “I Jornada Aragonesa de Nutrición y Dietética. Comer en la Escuela: Educación y Salud”: 15 de Febrero de 2008; SEDCA: Zaragoza, Spain, 2008; pp. 11–16. Available online: https://docplayer.es/74850940-Libro-de-ponencias-i-jornada-aragonesa-de-nutricion-y-dietetica.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Romeo, J.; Wärnberg, J.; Marcos, A. Valoración del estado nutricional en niños y adolescentes. Pediatr. Integral. 2007, XI, 297–304. Available online: https://skat.ihmc.us/rid=1K4L4B2BZ-1PRDPXD-1JX/NUTRICI%C3%93N%25%2020-%20PEDIATR%C3%8DA.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Durá, T. Influencia de la educación nutricional en el tratamiento de la obesidad infanto-juvenil. Nutr. Hosp. 2006, 21, 307–321. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112006000300004&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Alba-Martín, R. Prevalencia de obesidad infantil y hábitos alimentarios en educación primaria. Enferm. Glob. 2016, 15, 40–51. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412016000200003&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Pineda, E.; Bascunan, J.; Sassi, F. Improving the school food environment for the prevention of childhood obesity: What works and what doesn’t. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, 13176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurpinder-Singh, L. A review of the English school meal: ‘progress or a recipe for disaster’? Camb. J. Educ. 2021, 51, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranceta, J.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Dalmau, J.; Gil, A.; Lama, R.; Martin, M.A.; Suárez, V.M.; Belinchón, P.P.; Cortina, L.S. El comedor escolar: Situación actual y guía de recomendaciones. An. Pediatr. 2008, 69, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozo, S. Programa de Comedores Escolares para la Comunidad de Madrid: Repercusión en la Calidad de los Menús y en el Estado Nutricional. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2007. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/7883/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Aranceta, J.; Pérez, C. Guía para la restauración colectiva. Jano Med. Humanid. 2004, 67, 49–54. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=1056975 (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Soler, C. Soberanía alimentaria en las mesas del colegio. Rev. Soberanía Aliment. Biodivers. Cult. 2011, 10, 1–82. Available online: https://da1.soberaniaalimentaria.info/images/estudios/sob_al_mesas_colegio.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Llorens-Ivorra, C.; Soler-Rebollo, C. Aceptación de un menú escolar según la valoración de residuos del método de estimación visual Comstock. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet 2017, 21, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berradre-Sáenz, B.; Royo-Bordonada, M.A.; Bosqueda, M.J.; Moya, M.A.; López, L. Menú escolar de los centros de enseñanza secundaria de Madrid: Conocimiento y cumplimiento de las recomendaciones del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Gac. Sanit. 2015, 29, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz, A.M. Análisis de la calidad de las páginas web en los hospitales españoles. Enferm. Glob. 2007, 10, 1–13. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/eglobal/article/view/224 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Guardiola, R.; Gil, J.D.; Sanz, J.; Wanden-Berghe, C. Evaluating the quality of websites relating to diet and eating disorders. Health Info. Libr. J. 2011, 28, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa-Fuentes, M.C.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, E. Evaluación de la calidad de las páginas web con información sanitaria: Una revisión bibliográfica. Bid Textos Univ. Bibl. Doc. 2009, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Oliván, J.A.; Angós-Ullate, J.M.; Fernández-Ruiz, M.J. Criterios para evaluar la calidad de las fuentes de información en Internet. Scire 1999, 5, 99–113. Available online: https://ibersid.eu/ojs/index.php/scire/article/view/1119 (accessed on 27 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Sánchez, E. Criterios más utilizados para la evaluación de la calidad de los recursos de información en salud disponibles en Internet. ACIMED 2004, 12, 1. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1024-94352004000200004&lng=es (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Calvo-Calvo, M.A. Calidad y características de los sitios web de los hospitales españoles de gran tamaño. Rev. Esp. Doc. Cient. 2014, 37, e032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiménez-Pernett, J.; García-Gutiérrez, J.F.; Bermúdez-Tamayo, C.; Silva-Castro, M.M.; Tuneu, L. Evaluación de sitios web con información sobre medicamentos. Aten. Primaria 2009, 41, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bermúdez, C.; Jiménez, J.; García, J.F.; Azpilicueta, I.; Silva, M.M.; Babio, G.; Castaño, J.P. Cuestionario para evaluar sitios web sanitarios según criterios europeos. Aten. Primaria 2006, 38, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domínguez, A.; Iñesta, A. Evaluación de la calidad de las webs de centros de farmacoeconomía y economía de la salud en Internet mediante un cuestionario validado. Gac. Sanit. 2004, 18, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rancaño, I.; Rodrigo, J.A.; Villa, R.; Abdelsater, M.; Díaz, R.; Álvarez, D. Evaluación de las páginas web en lengua española útiles para el médico de atención primaria. Aten. Primaria 2003, 31, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, M.C.; Aguinaga, E.; Hernández, J.J. Evaluación de la calidad de las páginas web sanitarias mediante un cuestionario validado. Aten. Primaria 2011, 43, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olea, C. Calidad de las páginas web de asociaciones de diabetes en España. Rev. Esp. Común. Salud 2012, 3, 16–27. Available online: https://e-revistas.uc3m.es/index.php/RECS/article/view/3385 (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Peña-Palenzuela, N. Calidad de las páginas web con información sobre el cáncer de mama: Una revisión bibliográfica. Rev. Esp. Comun. Salud 2016, 7, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Lorente, M.; Guardiola-Wanden-Berghe, R. Evaluación de la calidad de las páginas Web sobre el Hospital a Domicilio: El Indicador de Credibilidad como factor pronóstico. Hosp. Domic. 2017, 1, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gil-Pérez, J.D. Internet como Generador de Opinión en la Juventud Española: Valoración de la Calidad y Credibilidad de las Páginas Web Más Consultadas por los Jóvenes Españoles. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 2011. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/24407/1/Tesis_Josefa_Gil_Perez.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Alvarado-Zeballos, S.; Nazario, M.A.; Taype-Rondan, A. Características de las páginas web en español que brindan información sobre aborto. Rev. Fac. Med. 2017, 65, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, E.; Calderón, A.; Palao, J.M.; Puigcerver, M.C. Diseño y validación de un cuestionario para evaluar la actitud percibida del profesor en clase y de un cuestionario para evaluar los contenidos actitudinales de los alumnos durante las clases de educación física en secundaria. Retos. Nuevas Tend. Educ. Fis. Deporte Recreación 2008, 14, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Iglesias, J.C.; Andrés-Rodríguez, N.F.; Fornos-Pérez, J.A. Validación de un cuestionario de conocimientos sobre hipercolesterolemia en la farmacia comunitaria. Seguim. Farmacoter. 2005, 3, 189–196. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.956.4268&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- García-Delgado, P.; Gastelurrutia-Garralda, M.A.; Baena-Parejo, M.I.; Fisac-Lozano, F.; Martínez-Martínez, F. Validación de un cuestionario para medir el conocimiento de los pacientes sobre sus medicamentos. Aten. Primaria 2009, 41, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carvajal, A.; Centeno, C.; Watson, R.; Martínez, M.; Sanz-Rubiales, Á. ¿Cómo validar un instrumento de medida de la salud? An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2011, 34, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García De Yébenes-Prous, M.J.; Rodríguez-Salvanés, F.; Carmona-Ortells, L. Validación de cuestionarios. Reumatol. Clin. 2009, 5, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad-Rodriguez, I.; Fernández-Ballart, J.; Cucó-Pastor, G.; Biarnés-Jordá, E.; Arija-Val, V. Validación de un cuestionario de frecuencia de consumo alimentario corto: Reproducibilidad y validez. Nutr. Hosp. 2008, 23, 242–252. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112008000300011&lng=es (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Nova, J.A.; Hernández-Mosqueda, J.S.; Tobón–Tobón, S. Juicio de expertos para la validación de un instrumento de medición del síndrome de burnout en la docencia. Ra Ximhai 2016, 12, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alfonso, L.; Bayarre-Vea, H.D.; Grau-Ábalo, J.A. Validación del cuestionario MBG (Martín-Bayarre-Grau) para evaluar la adherencia terapéutica en hipertensión arterial. Rev. Cuba. Salud Pública 2008, 34, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Sapena, N.; Galiana-Sánchez, M.E.; Bernabéu-Mestre, J. Evaluación del contenido sobre educación alimentaria en páginas web de servicios de catering: Estudio piloto en el ámbito escolar. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet 2014, 18, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azpipilicueta, I.; Bermúdez, C.; Silva, M.M.; Valverde, I.; Martiarena, A.; García, J.F.; Jiménez-Pernett, J.; Valls, L.T.; Dáder, M.J.F. Adecuación a los códigos de conducta para información biomédica en internet de sitios web útiles para el seguimiento farmacoterapéutico. Gac. Sanit. 2007, 21, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cumbreras, C.; Conesa, M.C. Usabilidad en las páginas web: Distintas metodologías, creación de una guía de evaluación heurística para analizar un sitio web, aplicación en enfermería. Enferm. Global. 2006, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeiras, N.; Meneses, J.A. Criterios y procedimientos de análisis en el estudio del discurso en páginas web: El caso de los residuos sólidos urbanos. Enseñ. Cienc. 2006, 24, 71–84. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/Ensenanza/article/view/73533 (accessed on 28 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Llinás, G.; Mira, J.J.; Pérez-Jover, V.; Tomás, O. En qué se fijan los internautas para seleccionar páginas web sanitarias. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2005, 20, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, P. La educación nutricional como factor de protección en los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria. Trastor. Conducta Aliment. 2009, 10, 1069–1086. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3214016 (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Téllez, M.; Orzáez, M.T. Una experiencia de educación nutricional en la escuela. OFFARM 2003, 22, 70–76. Available online: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-offarm-4-articulo-una-experiencia-educacion-nutricional-escuela-13049108 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Serrano, J.; Sáez, S. Recursos didácticos en educación para la salud. In Promoción y Educación para la Salud. Conceptos, Metodología, Programas; Sáez, S., Font, P., Pérez, R., Márquez, F., Eds.; Editorial Milenio: Lleida, Spain, 2001; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Orts-Cortes, M.I. Validez de Contenido del Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) en el Ámbito Europeo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 2011. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/21852/1/tesis_orts.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Cartín-Rojas, A.; Pascual-Barrera, A. Análisis de validez y reproducibilidad de un instrumento para sistemas nacionales de inocuidad de alimentos. Rev. Cient. Ecocienc. 2019, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrosa, I.; Suárez-Álvarez, J.; García-Cueto, E. Evidencias sobre la validez de contenido: Avances teóricos y métodos para su estimación. Acción Psicol. 2014, 10, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and Quantification of Content Validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–386. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3640358/ (accessed on 26 November 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrutia-Egaña, M.J.; Barrios-Araya, S.C.; Gutiérrez-Núñez, M.L.; Mayorga-Camus, M.P. Métodos óptimos para determinar validez de contenido. Educ. Méd. Super. 2014, 28, 547–558. Available online: http://www.ems.sld.cu/index.php/ems/article/view/301 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Sarabia-Cobo, C.M.; Alconero-Camarero, A.R. Claves para el diseño y validación de cuestionarios en Ciencias de la Salud. Enferm. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 69–73. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7142007 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Collet, C.; Nascimento, J.V.; Folle, A.; Ibáñez, S.J. Construcción y validación de un instrumento para el análisis de la formación deportiva en voleibol. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2018, 19, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilbert, G.; Prion, S. Making Sense of Methods and Measurement: Lawshe’s Content Validity Index. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2016, 12, 530–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Moral, R.; Pérula de Torres, L.A. Validez y fiabilidad de un instrumento para evaluar la comunicación clínica en las consultas: El cuestionario CICAA. Aten. Primaria 2006, 37, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pedraza, L.O.; Sierra, F.; Salazar, A.M.; Hernández, A.M.; Ariza, M.J.; Montalvo, M.C.; Plata, J.; Muñoz, Y.; Díaz, J.M.; Piñeros, C. Acuerdo intra-interobservador en las pruebas Minimental State Examination (MMSE) y Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA test) aplicados por personal en entrenamiento. Acta Neurol. Colomb. 2015, 32, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante-Ruiz, S.L.; Rodríguez-García, J.; Ríos-García, J.J.; Fernández-Torrico, J.M.; Cano-Plasencia, G.; Echevarría-Ruiz de Vargas, C. Variabilidad intra- e interobservador en la medición digital del ángulo de Cobb en la escoliosis idiopática. Rehabilitación 2016, 50, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens-Ivorra, C.; Arroyo-Bañuls, I.; Quiles-Izquierdo, J.; Richart-Martínez, M. Fiabilidad de un cuestionario para evaluar el equilibrio alimentario de menús escolares. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. Órgano Of. Soc. Latinoam. Nutr. 2017, 67, 251–259. Available online: http://www.alanrevista.org/ediciones/2017/4/art-2 (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Girabent-Farrés, M.; Monné-Guasch, L.; Bagur-Calafat, C.; Fagoaga, J. Traducción y validación al español del módulo neuromuscular de la escala Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL): Evaluación de la calidad de vida percibida por padres de niños de 2-4 años con enfermedades neuromusculares. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 66, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez-Molina, C.; Lázaro-Alcay, J.J.; Ullán-de la Fuente, A.M. Adaptación transcultural de la escala Induction Compliance Checklist para la evaluación del comportamiento del niño durante la inducción de la anestesia. Enferm. Clín. 2018, 28, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arias-Rivera, S.; Raurell-Torreda, M.; Thuissard-Vasallo, I.J.; Andreu-Vázquez, C.; Hodgson, C.L. Adaptación y validación de la ICU Mobility Scale en España. Enferm. Intensiva 2020, 31, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma-Leal, X.; Escobar-Gómez, D.; Chillón, P.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, F. Fiabilidad de un cuestionario de modos, tiempo y distancia de desplazamiento en estudiantes universitarios. Retos 2019, 37, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items of the Version 2 Questionnaire by Sections Reliability | Mean | Stdev | CVI (1) | CVI (2) |

| 1. Is the author(s) identified on the website? | 4.71 | 0.49 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 2. Is a contact address for the catering company provided? | 4.86 | 0.38 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 3. Is the information up to date? | 4.29 | 0.95 | 71.40 | 100.00 |

| 4. Is the protection of personal data and privacy specified? | 4.29 | 0.76 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 5. Does the website indicate the quality certificates of the catering company? | 4.14 | 0.90 | 71.40 | 100.00 |

| 6. Does it contain an internal search engine for the information contained on the website? | 3.86 | 1.35 | 71.40 | 71.40 |

| Design | ||||

| 7. Does the website have an attractive and original graphic and multimedia design? | 4.29 | 0.76 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 8. Is the website properly structured and organised? | 4.86 | 0.38 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 9. Does it include a site map? | 4.43 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 10. Does it have a clear and appropriate language for the user? | 4.71 | 0.49 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 11. Is the font size and colour contrast appropriate? | 4.14 | 0.69 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 12. Is the information contained on the website in more than one language? | 4.00 | 0.82 | 71.40 | 100.00 |

| Navigation | ||||

| 13. Is the website accessible and easy to navigate? | 4.86 | 0.38 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 14. Does it have an adequate browsing speed? | 4.14 | 0.90 | 71.40 | 100.00 |

| 15. Is it easy to find content and search the website? | 4.71 | 0.76 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 16. Does it have downloadable material? | 4.29 | 0.95 | 71.40 | 100.00 |

| 17. Are there recommended links and are they up to date? | 4.29 | 0.76 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 18. Does it have online help? | 4.29 | 0.95 | 71.40 | 100.00 |

| 19. Is the site free of advertising? | 4.86 | 0.38 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Content | ||||

| 20. Is the objectives or mission of the caterer reflected on the website? | 4.29 | 0.95 | 71.40 | 100.00 |

| 21. Does it have a section on food, nutrition or dietetics? | 4.43 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 22. Is the information on the website objective? | 4.86 | 0.38 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 23. Is the information comprehensible and unambiguous? | 4.86 | 0.38 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 24. Is the information nutritionally correct and adequate? | 4.57 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 25. Is the content endorsed by competent professionals? | 4.57 | 0.53 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 26. Does it relate nutrition to health? | 4.57 | 0.53 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 27. Is the importance of physical exercise indicated? | 4.29 | 0.76 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 28. Does the caterer participate in food and nutrition education programmes? | 4.43 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 29. Are special menus provided for students with specific therapeutic or cultural needs? | 4.57 | 0.53 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 30. Do you provide nutritional information and recommendations for supplementation of the school menu? | 4.57 | 0.53 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 31. Do you have private access to school menus for parents? | 4.71 | 0.49 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 32. Is the role of educators and their training indicated? | 4.29 | 0.76 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 33. Does the school have a separate website specifically for food and nutrition? | 4.00 | 1.00 | 57.10 | 100.00 |

| 34. Does the website cite examples or show real cases? | 3.86 | 0.90 | 57.10 | 100.00 |

| Educational Activities | ||||

| 35. Are there any activities? | 4.57 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 36. Informative talks | 4.43 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 37. Gastronomic days | 4.57 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 38. Cooking workshops | 4.57 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| 39. Healthy cooking recipes | 4.71 | 0.49 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 40. Other | 4.43 | 0.79 | 85.70 | 100.00 |

| Global | 4.44 | 0.71 | 87.00 | 99.00 |

| OBSERVER 1 | OBSERVER 2 | ICC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Stdev | Mean | Stdev | ||

| Reliability | 4.57 | 1.073 | 4.60 | 0.968 | 0.992 |

| Design | 4.73 | 1.048 | 4.50 | 1.106 | 0.871 |

| Navigation | 6.53 | 1.279 | 6.27 | 1.437 | 0.972 |

| Content | 10.20 | 3.708 | 10.23 | 3.626 | 0.999 |

| Educational Activities | 3.87 | 2.030 | 3.80 | 2.041 | 0.996 |

| Total | 29.90 | 6.880 | 29.40 | 6.806 | 0.996 |

| Catering Website | |||

| Predictors of quality | |||

| Reliability | YES | NO | |

| 1. Is the author(s) identified on the website? 2. Is a contact address of the catering company provided? 3. Does the website indicate when it was updated? 4. Is the protection of personal data and privacy specified? 5. Does the website indicate the quality certificates of the catering company? 6. Does it contain an internal search engine for the information contained on the website? | |||

| Design | YES | NO | |

| 7. Does the website have an attractive and original graphic and multimedia design? 8. Is the website properly structured and organised? 9. Does it include a site map? 10. Does it have a clear and appropriate language for the user? 11. Is the font size and contrasting colour appropriate? 12. Is the information contained on the website in more than one language? | |||

| Navigation | YES | NO | |

| 13. Is the website accessible and easy to navigate? 14. Does it have an adequate browsing speed? 15. Is it easy to find content on the website? 16. Does it have downloadable material? 17. Are there any recommended links? 18. Does the website have access to social networking sites? 19. Does it have online help? 20. Is the website free of advertising? | |||

| Specific food education content | |||

| Contents | YES | NO | |

| 21. Does the website reflect the objectives or mission of the caterer? 22. Does it have a section on food, nutrition or dietetics? 23. Is the information contained on the website objective and nutritionally adequate? 24. Is the information comprehensible? 25. Is the content endorsed by competent professionals? 26. Is food related to health? 27. Is the importance of physical exercise indicated? 28. Does the caterer participate in educational programmes on food and nutrition? 29. Are special menus provided for pupils with specific dietary or cultural needs? 30. Do you provide nutritional information on the school menu? 31. Do you provide recommendations for supplementation of the school menu? 32. Do you have private access for parents to the school menu? 33. Is the role of educators and their training indicated? 34. Does the school have a separate website specifically for food and nutrition? 35. Does the website cite examples or show real cases? | |||

| Educational activities | YES | NO | |

| 36. Do activities take place? | |||

| What kind of activities does the caterer carry out? | 37. Informative talks 38. Gastronomic days 39. Cooking workshops 40. Healthy cooking recipes 41. Other | ||

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Predictors of quality | |

| Reliability | |

| Authorship | Person/people or company responsible for the content of the website. |

| Contact address | Address, e-mail address, telephone number, etc. |

| Updating | Date of last modification of the website. |

| Privacy | Data protection and user privacy policy. |

| Certification | Catering quality, food safety, environmental, etc., certifications. |

| Search | Mechanism for searching, consulting and locating the contents of the website. |

| Design | |

| Graphic design | Graphic and multimedia design of the website. |

| Structure | Structure and organisation of the website. |

| Site map | Site map to facilitate the search of contents. |

| Legibility | Language and expression of the contents of the website. |

| Form and colour | Font size and contrasting colour on the website. |

| Language | Possibility of reading the website in more than one language. |

| Navigation | |

| Accessibility | Easy access to the information contained in the pages without limitation. |

| Speed | Adequate browsing speed, web page loading time of less than 5 s. Adequate speed is considered adequate if it has a waiting time of less than 5 s. |

| Ease | Ease or not of finding content on the website. |

| Downloads | Existence of any kind of downloadable material, photos, documents, etc. |

| Links | Existence of links on the website that work correctly. |

| Social Networking | Existence of hyperlinks to access social networks, Facebook, Twitter, … |

| Help | Online help for queries from the website, with chat, telephone, … |

| Advertising | No advertising or promotion of brands or collaborating companies. |

| Specific Contents | |

| Content | |

| Purpose | Objective or mission of the services provided by the catering service. |

| Food and nutrition section | Existence of a specific section on food, nutrition or dietetics on the website. |

| Objectivity | Information expressed in an objective and nutritionally adequate manner. |

| Understandable | Information expressed in an understandable and unambiguous way. |

| Endorsed | Information endorsed by professional and academic persons or institutions. |

| Health | Content relates nutrition to health effects. |

| Physical exercise | The content expresses the importance of physical exercise as part of healthy habits. |

| Collaboration | The catering service collaborates with an established educational programme or has one of its own. |

| Special menus | The catering service provides special menus for pupils with diabetes, food allergies, coeliac disease, religious or cultural beliefs. |

| Nutritional information | Nutritional information of the school menu indicating calorie, protein, fat and carbohydrate intake. |

| Recommendations | Recommendations for supplementing the school menu on the most appropriate food intake for the rest of the day. |

| Private access | Private access to the school’s monthly menus from the website. |

| Monitors | Indication of the roles of educators or monitors and their training. |

| Food-nutrition website | Separate food and nutrition specific webpage separate from the catering website. |

| Examples | Citation of examples or sample real cases of catering services. |

| Educational Activities | |

| Activities | Activities aimed at educating about food, nutrition, etc., are carried out. |

| Talks | Informative talks on food, nutrition and dietetics. |

| Conferences | Gastronomic days on regions or countries, themes, festivities, etc. |

| Workshops | Cooking workshops, where children can learn about cooking, food, etc. |

| Reception | Healthy cooking recipes. |

| Other | Carrying out activities other than those mentioned above. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rico-Sapena, N.; Galiana-Sánchez, M.E.; Moncho, J. Validation of a Questionnaire of Food Education Content on School Catering Websites in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063685

Rico-Sapena N, Galiana-Sánchez ME, Moncho J. Validation of a Questionnaire of Food Education Content on School Catering Websites in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063685

Chicago/Turabian StyleRico-Sapena, Nuria, María Eugenia Galiana-Sánchez, and Joaquín Moncho. 2022. "Validation of a Questionnaire of Food Education Content on School Catering Websites in Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063685