LGBTQ+ Youth’s Identity Development in the Context of Peer Victimization: A Mixed Methods Investigation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Peer Victimization

1.2. Combatting Peer Victimization: Social Support as a Buffer

1.3. Peer Victimization: Outness as a Moderator

1.4. Rationale for Mixed Methods and Transformative Framework

1.5. Current Study

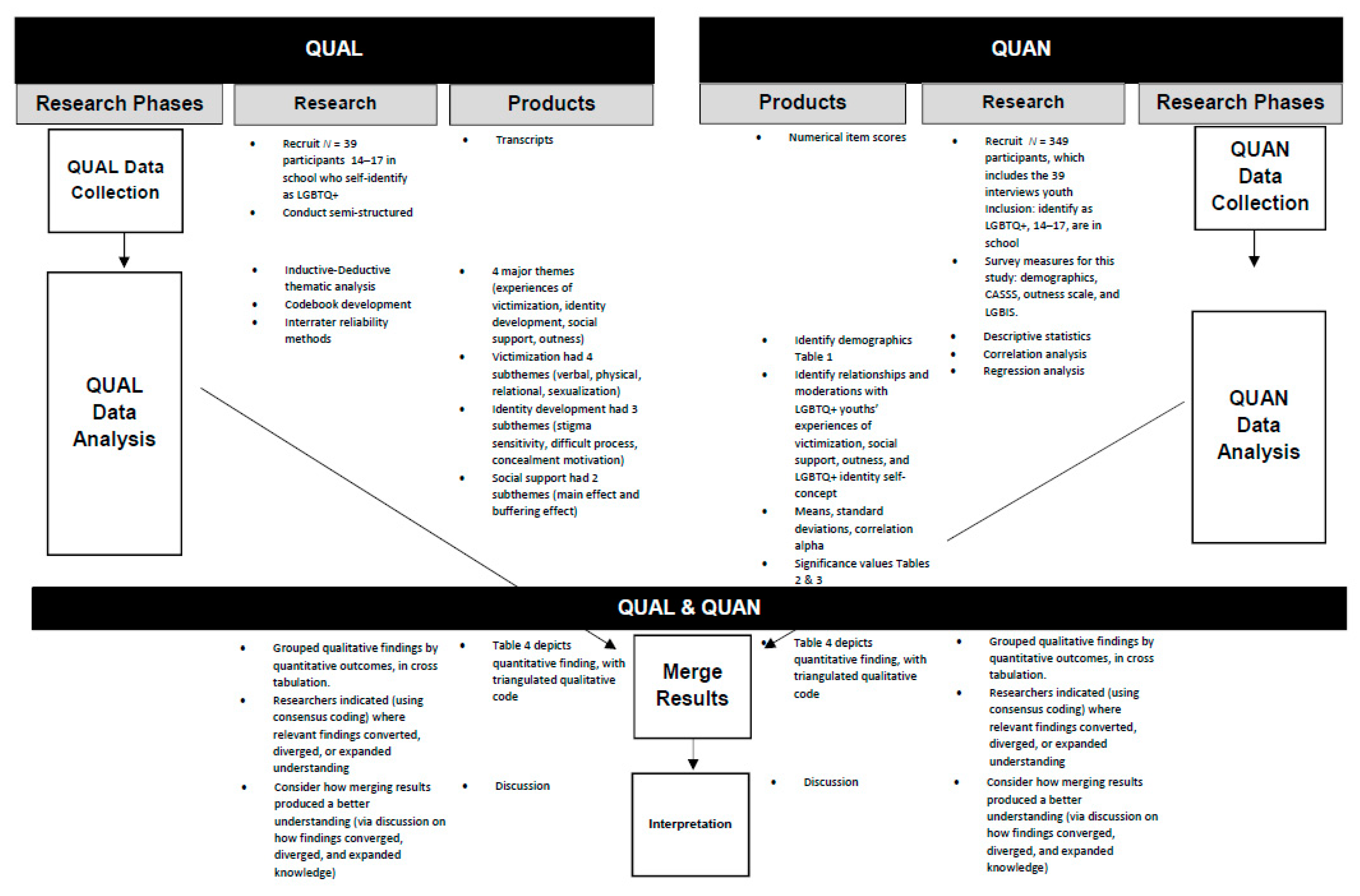

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Methods

2.4.1. Qualitative Instruments

2.4.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative Coding

Reviewing Codes for Current Analysis

Trustworthiness

2.5. Quantitative Methodology

2.5.1. Measures

LGBIS

Peer Victimization

Child and Adolescent Scale of Social Support-Revised (CASSS-R)

Outness Inventory

2.5.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

3.1.2. Associations between Peer Victimization and LGBTQ+ Identity Outcomes

3.1.3. Moderating Effects of Outness and Social Support

3.2. Victimization

3.2.1. Verbal

3.2.2. Physical

3.2.3. Relational

3.2.4. Sexualization

3.3. Identity Development

3.3.1. Internalized Stigma Sensitivity

3.3.2. Difficult Process

3.3.3. Concealment Motivation

3.4. Social Support

3.4.1. Main Effect

3.4.2. Buffering Effect

3.5. Outness

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Effects of Victimization

4.2. Moderating Factors

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erikson, E. Identity, Youth and Crisis. Norton Company: New York, NY, 1968. Behav. Sci. 1969, 2, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, V.C. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. J. Homosex. 1979, 3, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troiden, R.R. Becoming homosexual: A model of gay identity acquisition. Psychiatry J. Study Interpers. Process. 1979, 4, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, J.J.; Kendra, M.S. Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: The lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 2, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H.; Frost, D.M. Minority Stress and the Health of Sexual Minorities. In Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Gower, A.; Forster, M.; Gloppen, K.; Johnson, A.Z.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Connett, J.E.; Borowsky, I.W. School practices to foster LGBT-supportive climate: Associations with adolescent bullying involvement. Prev. Sci. 2018, 6, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guz, S.; Kattari, S.K.; Atteberry-Ash, B.; Klemmer, C.L.; Call, J.; Kattari, L. Depression and suicide risk at the cross-section of sexual orientation and gender identity for youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 2, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal, M.P.; Dietz, L.J.; Friedman, M.S.; Stall, R.; Smith, H.A.; McGinley, J.; Thoma, B.C.; Murray, P.J.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Brent, D.A. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 2, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birkett, M.; Russell, S.T.; Corliss, H.L. Sexual-orientation disparities in school: The mediational role of indicators of victimization in achievement and truancy because of feeling unsafe. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 6, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, M.; Gervais, J.; Hébert, M. Internalized homophobia as a partial mediator between homophobic bullying and self-esteem among sexual minority youths in Quebec (Canada). Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2014, 3, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olweus, D. Bully/victim problems among school children in Scandinavia. Psykologprofesjonen 1987, 12, 395–413. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, D. Bullies on the Playground. In Children on Playgrounds Research Perspective and Application; Heart, C., Ed.; University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 85–128. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, N.; Lindquist, L.; Machek, G.; Cochran, B. School belonging, school victimization, and the mental health of LGBT young adults; Implications for school psychologists. Sch. Psychol. Forum 2014, 8, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw, J.G.; Palmer, N.A.; Kull, R.M. Reflecting Resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 55, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Trevor Project Research Brief: Bullying and Suicide Risk among LGBTQ Youth. Available online: www.thetrevorproject.org (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Lasser, J.; Tharinger, D. Visibility management in school and beyond: A qualitative study of gay, lesbian, bisexual youth. J. Adolesc. 2003, 26, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.A.; Wynn, R.D.; Webb, K.W. This really interesting juggling act: How university students manage disability/queer identity disclosure and visibility. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2019, 4, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, J.G.; Palmer, N.A.; Kull, R.M.; Greytak, E.A. The effect of negative school climate on academic outcomes for LGBT youth and the role of in-school supports. J. Sch. Violence 2012, 12, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.A.; Bell, T.S.; Benibgui, M.; Helm, J.L.; Hastings, P.D. The buffering effect of peer support on the links between family rejection and psychosocial adjustment in LGB emerging adults. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 35, 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Lin, H.-C.; Chen, M.-H.; Ko, N.-Y.; Chang, Y.-P.; Lin, I.-M.; Yen, C.-F. Effects of traditional and cyber homophobic bullying in childhood on depression, anxiety, and physical pain in emerging adulthood and the moderating effects of social support among gay and bisexual men in Taiwan. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trujillo, M.A.; Perrin, P.B.; Sutter, M.; Tabaac, A.; Benotsch, E.G. The buffering role of social support on the associations among discrimination, mental health, and suicidality in a transgender sample. Int. J. Transgenderism 2017, 1, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.A.; Birkett, M.A.; Mustanski, B. Typologies of social support and associations with mental health outcomes among LGBT youth. LGBT Health 2015, 2, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poteat, V.P.; Watson, R.J.; Fish, J.N. Teacher support moderates associations among sexual orientation identity outness, victimization, and academic performance among LGBQ+ youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 8, 1634–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.T.; Toomey, R.B.; Ryan, C.; Diaz, R.M. Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 2014, 6, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestone, W.A. Meaning in method: The rhetoric of quantitative and qualitative research. Educ. Res. 1987, 7, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/node/52625/print (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Creswell, J.; Clark, V.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Transformative paradigm: Mixed methods and social justice. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 3, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health; Minkler, M., Wallerstein, N., Eds.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.J.; Palmer, N.A.; Reisner, S.L. Online social support as a buffer against online and offline peer and sexual victimization among U.S. LGBT and non-LGBT youth. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 39, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 2, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongco, M.D.C. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 2, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiperman, S.; DeLong, G.; Varjas, K.; Meyers, J. Providing inclusive strategies for practitioners and researchers working with gender and sexually diverse youth without parental/guardian consent. In Supporting Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Diversity in K-12 Schools; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saillard, E.K. Systematic versus interpretive analysis with two CAQDAS packages: NVivo and MAXQDA. Forum Qual. Soz./Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, B.K. Advances in qualitative research. Handb. Sch. Psychol. 2009, 4, 30–53. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, G.G.; Anselm, L.S. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Aldine Transaction: New Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- House, J.S. Work Stress and Social Support; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1981; Available online: http://books.google.com/books?id=qO2RAAAAIAAJ (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Neufeld, A.; Harrison, M.J. Unfulfilled expectations and negative interactions: Nonsupport in the relationships of women caregivers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 4, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Bitencourt, C.C.; dos Santos, A.C.M.Z.; Teixeira, E.K. Thematic content analysis: Is there a difference between the support provided by the MAXQDA® and NVivo® software packages? Rev. Adm. UFSM 2015, 9, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeman, R.; Gottman, J.M. Observing Interaction: An Introduction to Sequential Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, K.M.; McLellan, E.; Kay, K.; Milstein, B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cam J. 1998, 10, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberman, M.A.; Miles, M.B. Data Management and Analysis Methods. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 428–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/naturalistic-inquiry/book842 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 8, 191–215. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1977-25733-001 (accessed on 9 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Goodell, S.L.; Stage, C.V.; Cooke, N.K. Practical qualitative research strategies: Training interviewers and coders. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 8, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayall, B. Conversations with Children: Working with Generational Issues. In Research with Children, 2nd ed.; Christensen, P., James, A., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshirne, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg, R. School bullying and fitting into the peer landscape: A grounded theory field study. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 39, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynard, H.; Joseph, S. Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggress. Behav. 2000, 2, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, C.; Demaray, M. Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychol. Sch. 2002, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. The Self-Perception Profile for Children: Revision of The Perceived Competence Scale for Children; University of Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 1985; unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow, E.F.; Ullman, D.G. Assessing social support in elementary school children: The survey of children’s social support. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1989, 18, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J.; Fassinger, R. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2000, 2, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 6, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiperman, S.; Varjas, K.; Meyers, J.; Howard, A. LGB Youth’s perceptions of social support: Implications for school psychologists. Sch. Psychol. Forum 2014, 8, 75–90. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sarah-Kiperman/publication/274062826_LGB_Youth’s_Perceptions_of_Social_Support_Implications_for_School_Psychologists/links/56609b3408ae4931cd598ca2/LGB-Youths-Perceptions-of-Social-Support-Implications-for-School-Psychologists.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed.; Guavain, M., Cole, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 3, pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

| Quantitiative Sample n (%) | Qualitative Sample n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | 349 (100) | 39 (100) |

| Age | ||

| 14 | 70 (20.1) | 7 (17.9) |

| 15 | 101 (28.9) | 8 (20.5) |

| 16 | 86 (24.6) | 10 (25.6) |

| 17 | 79 (22.6) | 14 (35.9) |

| 18 | 10 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 236 (67.6) | 25 (33.3) |

| Black/African American | 16 (4.6) | 5 (12.8) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 29 (8.3) | 4 (10.3) |

| Asian Pacific Islander | 10 (2.9) | 1 (2.6) |

| Mixed | 41 (11.7) | 2 (5.1) |

| Other | 5 (1.4) | 2 (5.1) |

| Sexual Orientation Label | ||

| Gay | 32 (9.2) | 3 (7.7) |

| Lesbian | 54 (15.5) | 11 (28.2) |

| Bisexual | 78 (22.3) | 7 (17.9) |

| Pansexual | 67 (19.2) | 17 (43.6) |

| Heterosexual | 2 (0.6) | 1 (2.6) |

| Asexual | 47 (13.5) | 0 (0) |

| Gender Identity Label | ||

| Male | 15 (4.3) | 6 (15.4) |

| Female | 104 (29.8) | 20 (51.8) |

| Transgender Male | 59 (16.9) | 2 (5.1) |

| Transgender Female | 4 (1.1) | 1 (2.6) |

| Other * | 164 (47) | 10 (25.6) |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Peer victimization | -- | ||||||||

| 2. Outness to old straight friends | 0.15 ** | -- | |||||||

| 3. Outness to new straight friends | 0.01 | 0.30 *** | -- | ||||||

| 4. Classmate support | −0.31 *** | 0.01 | 0.01 | -- | |||||

| 5. Close friend support | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.32 *** | -- | ||||

| 6. Stigma sensitivity | 0.20 *** | −0.11 * | −0.23 *** | −0.10 | −0.15 ** | -- | |||

| 7. Difficult process | 0.14 * | −0.14 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.10 | −0.05 | 0.34 *** | -- | ||

| 8. Concealment motivation | −0.01 | −0.20 *** | −0.42 *** | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.32 *** | 0.34 *** | -- | |

| 9. Identity dissatisfaction | 0.04 | −0.11 * | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.23 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.26 *** | -- |

| M (SD) | 26.60 (8.4) | 4.66 (2.07) | 4.63 (2.38) | 35.02 (12.5) | 56.10 (11.6) | 12.74 (3.3) | 11.67 (3.8) | 10.76 (3.5) | 11.93 (5.1) |

| Demographic | Stigma Sensitivity | Difficult Process | Concealment Motivation | Identity Dissatisfaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | −2.69 | 0.93 ** | −2.58 | 1.06 * | −2.29 | 1.00 * | −1.23 | 1.42 |

| Female | −0.59 | 0.42 | −0.57 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.45 | −0.18 | 0.64 |

| Trans | −0.23 | 0.50 | −0.93 | 0.57 | −1.68 | 0.53 ** | 3.02 | 0.76 *** |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black | 0.13 | 0.88 | −0.97 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 0.94 | −0.41 | 1.38 |

| Asian | −0.02 | 1.07 | 1.72 | 1.22 | 1.37 | 1.15 | 1.26 | 1.63 |

| Latinx | −0.51 | 0.68 | −0.06 | 0.77 | 1.22 | 0.72 | 0.28 | 1.03 |

| Native American | 1.25 | 1.19 | 1.24 | 1.35 | 2.26 | 1.27 | 0.74 | 1.81 |

| Multiethnic | −0.64 | 0.56 | −0.58 | 0.65 | −0.04 | 0.60 | −1.88 | 0.86 * |

| Other | −1.30 | 1.49 | −2.68 | 1.69 | 0.06 | 1.78 | −1.67 | 2.26 |

| Geographic Location | ||||||||

| Urban | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0.50 | −0.43 | 0.47 | −0.90 | 0.67 |

| Rural | 0.02 | 0.48 | 1.31 | 0.54 * | 0.28 | 0.51 | 0.84 | 0.73 |

| Peer Victimization | 0.08 | 0.02 *** | 0.06 | 0.03 * | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.03 |

| Finding | Quantitative Statistic Result | Qualitative Experiences | 1 Converge, 2 Diverge, 3 Expand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects of Peer Victimization on Identity Development | |||

| ↑ peer victimization, ↑ stigma sensitivity | Youth who experienced greater peer victimization also experienced greater stigma sensitivity. | Youth justified their victimization as a product of who they are and their LGBTQ+ identity. | Convergent |

| ↑ peer victimization, ↑ difficult process | Youth who experienced greater peer victimization also experienced coming out as a more difficult process. | Youth discussed the challenge of processing their LGBTQ+ identity in the context of experiencing and observing LGBTQ+ specific victimization. | Convergent |

| Moderation Findings | |||

| Independent variable ↑ peer victimization Moderated by X ↑ classmate support; X ↑ close friend support Outcome = ↓ difficult process | Youth experiencing more peer victimization experienced coming out as a more difficult process if they had low, but not high, levels of classmate support; high levels of classmate social support buffer against the negative effects of peer victimization on the difficult process. | LGBTQ+ youth discussed when they are victimized how their friends and peers can alleviate the difficult process of LGBTQ+ identity development by making them feel better and standing up for themselves. | Convergent |

| LGBTQ+ peers and close friends emphasized as reliable sources of support. | Expand | ||

| Independent variable ↑ peer victimization Moderated by X ↑ outness to new straight friends Outcome = ↑ concealment motivation | Youth experiencing more peer victimization perceived greater motivation to conceal their LGBTQ+ identity if they were more out to their new straight friends. | When out to straight friends, friends distanced selves (experienced as relational bullying). | Convergent |

| When out to straight friends, friends also supported youth and endorsed feeling glad they were out. | Divergent | ||

| Reported feeling connected and relieved when out to other LGBTQ+ close friends and peers. | Expand | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiperman, S.; Schacter, H.L.; Judge, M.; DeLong, G. LGBTQ+ Youth’s Identity Development in the Context of Peer Victimization: A Mixed Methods Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073921

Kiperman S, Schacter HL, Judge M, DeLong G. LGBTQ+ Youth’s Identity Development in the Context of Peer Victimization: A Mixed Methods Investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073921

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiperman, Sarah, Hannah L. Schacter, Margaret Judge, and Gabriel DeLong. 2022. "LGBTQ+ Youth’s Identity Development in the Context of Peer Victimization: A Mixed Methods Investigation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073921