The Impact of Delivering School-Based Wellness Programs for Emerging Adult Facilitators—A Quasi-Controlled Clinical Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

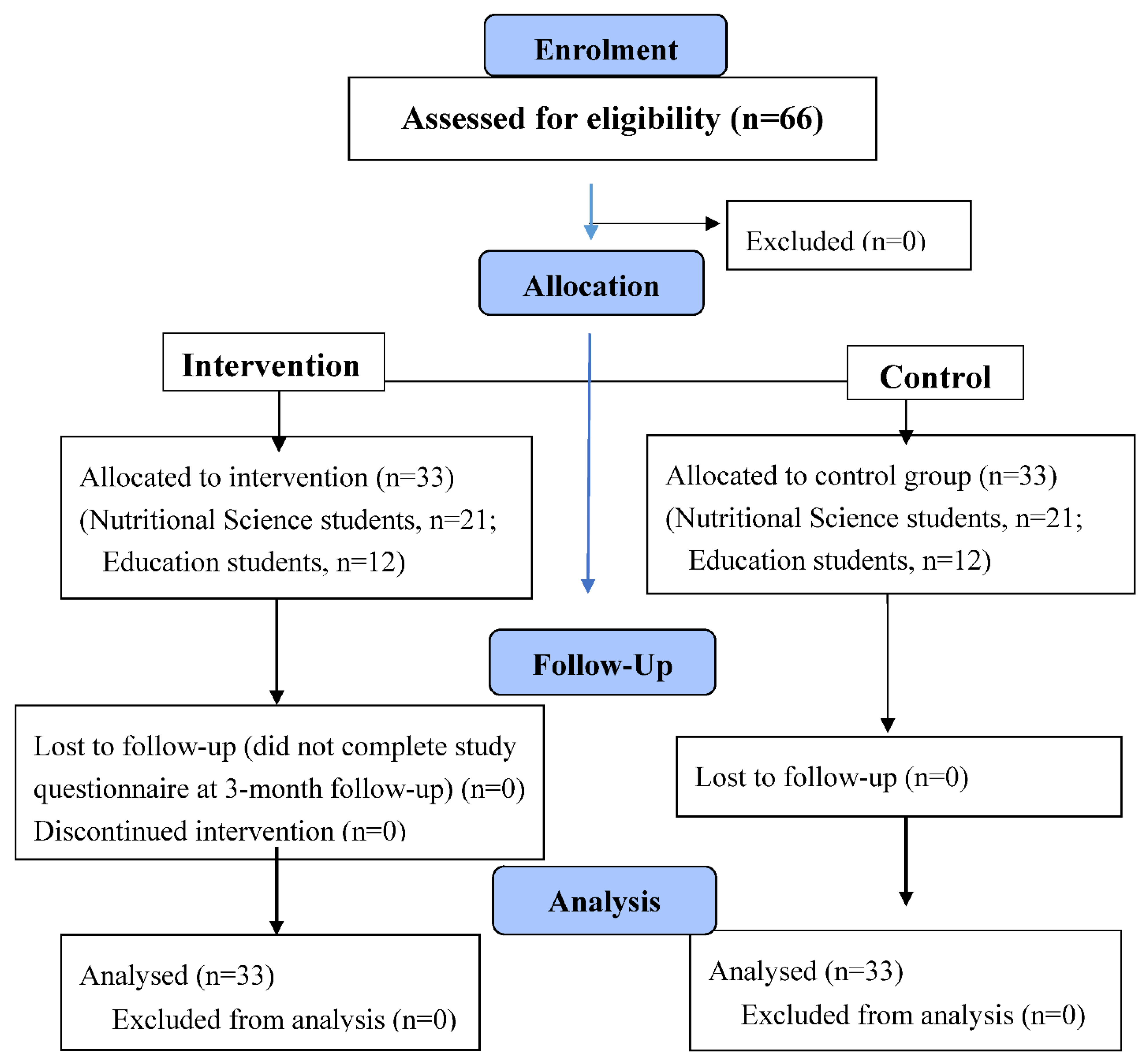

2.1. Design and Sample Recruitment

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Ethical Procedures

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Study Population

2.6. Facilitator Training

2.7. Data Collection Procedure

2.8. Outcome Measures and Variables

2.9. Personal and Demographic Information

2.10. Media Literacy and Pressures by Media

2.11. Self-Esteem, Body-Esteem Scale, and Behaviors and Perceptions Associated with Eating Disorders

2.12. Satisfaction Assessment

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Differences in Outcome Measures between Facilitators and Comparisons

3.2. Differences in Outcome Measures between Facilitators and Comparisons along Assessment Times

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Trial Registration

Abbreviations

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SATAQ-4 | Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 |

| RSE | Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale |

| BES | The Body Esteem Scale |

| Eat-26 | The Eating Attitudes Test |

| ADVER | Advertising scale |

References

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.; Crapnell, T.; Lau, L.; Bennett, A.; Lotstein, D.; Ferris, M.; Kuo, A. Emerging adulthood as a critical stage in the life course. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Halfon, N., Forrest, C., Lerner, R., Faustman, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howard, L.M.; Romano, K.A.; Heron, K.E. Prospective changes in disordered eating and body dissatisfaction across women’s first year of college: The relative contributions of sociocultural and college adjustment risk factors. Eat. Behav. 2020, 36, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganson, K.T.; Mitchison, D.; Murray, S.B.; Nagata, J.M. Legal performance-enhancing substances and substance use problems among young adults. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, E.J. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. J. Drug Issues 2005, 35, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C.N.; Shaw, H.; Rohde, P. Meta-analytic review of dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs: Intervention, participant, and facilitator features that predict larger effects. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 70, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Las Hayas, C.; Izco-Basurko, I.; Fullaondo, A.; Gabrielli, S.; Zwiefka, A.; Hjemdal, O.; Gudmundsdottir, D.G.; Knoop, H.H.; Olafsdottir, A.S.; Donisi, V.; et al. UPRIGHT, a resilience-based intervention to promote mental well-being in schools: Study rationale and methodology for a European randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doley, J.R.; McLean, S.A.; Griffiths, S.; Yager, Z. Designing body image and eating disorder prevention programs for boys and men: Theoretical, practical, and logistical considerations from boys, parents, teachers, and experts. Psychol. Men Masc. 2020, 22, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.M.; Renner, B.; Clarys, P.; Lien, N.; Lakerveld, J.; Deliens, T. Understanding eating behavior during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: A literature review and perspective on future research directions. Nutrients 2018, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gasanov, E.; Abu Ahmad, W.; Golan, M. Assessment of “young in favor of myself”: A school-based wellness program for preadolescents. EC Psychol. Psychiatr. 2018, 7, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.C.; Wang, L.S.; Lin, Y.H.; Lee, I. The effect of a peer-mentoring strategy on student nurse stress reduction in clinical practice. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2011, 58, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astin, A.W.; Sax, L.J. How undergraduates are affected by service participation. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1998, 39, 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Bene, K.L.; Bergus, G. When learners become teachers: A review of peer teaching in medical student education. Fam. Med. 2014, 46, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crenshaw, C.E.; Mozen, D.M.; Dalton, W.T.; Slawson, D.L. Reflections from an undergraduate student peer facilitator in the team up for healthy living school-based obesity prevention project. Int. J. Health Sci. Educ. 2014, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jennings, J.M.; Howard, S.; Perotte, C.L. Effects of a school-based sexuality education program on peer educators: The teen PEP model. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gilmartin, H.; Goyal, A.; Hamati, M.C.; Mann, J.; Saint, S.; Chopra, V. Brief mindfulness practices for healthcare providers—A systematic literature review. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 1219.e1–1219.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McLeod, D.A.; Jones, R.; Cramer, E.P. An evaluation of a school-based, peer-facilitated, healthy relationship program for at-risk adolescents. Child. Sch. 2015, 37, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, L.J.; McKennon, S.; Danielson, J.; Knuth, J.; Odegard, P. An elective course to train student pharmacists to deliver a community-based group diabetes prevention program. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, V.; Forrest, S.; Oakley, A. What influences peer-led sex education in the classroom? A view from the peer educators. Health Educ. Res. 2002, 17, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saad, A.; Rampal, L.; Sabitu, K.; AbdulRahman, H.; Awaisu, A.; AbuSamah, B.; Ibrahim, A. Impact of a customized peer-facilitators training program related to sexual health intervention. Int. Health 2012, 4, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, E.P.; Ross, A.I.; McLeod, D.A.; Jones, R. The impact on peer facilitators of facilitating a school-based healthy relationship program for teens. Sch. Soc. Work J. 2015, 40, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, C.S.; Golonka, M.; Costanzo, P.R. Evaluating the impact of a substance use intervention program on the peer status and influence of adolescent peer leaders. Prev. Sci. 2012, 13, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Golan, M.; Hagay, N.; Tamir, S. The effect of “in favor of myself”: Preventive program to enhance positive self and body image among adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaefer, L.M.; Burke, N.L.; Thompson, J.K.; Dedrick, R.F. Development and validation of the sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bachner-Melman, R.; Zohar, A.H.; Elizur, Y.; Kremer, I.; Golan, M.; Ebstein, R. Protective self-presentation style: Association with disordered eating and anorexia nervosa mediated by sociocultural attitudes towards appearance. EWD 2009, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, K. The Contribution of General and Sexually Specific Personal and Interpersonal Resources to Risky Sexual Behavior among Adolescents; University of Haifa: Haifa, Israel, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, B.K.; Mendelson, M.J.; White, D.R. Body-esteem scale for adolescents and adults. J. Personal. Assess. 2001, 76, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouallem, M.; Golan, M. “In favor of myself for athletes”: A controlled trial to improve disordered eating, body-image and self-care in adolescent female aesthetic athletes. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2019, 8, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koslowsky, M.; Scheinberg, Z.; Bleich, A.; Mark, M.; Apter, A.; Danon, Y.; Solomon, Z. The factor structure and criterion validity of the short form of the eating attitudes test. J. Personal. Assess. 1998, 58, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Fisher, P. Peer education and empowerment: Perspectives from young women working as peer educators with Home-Start. Stud. Educ. Adults 2018, 50, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; McGregor, D. Peer teacher training for health professional students: A systematic review of formal programs 13 education 1303 specialist studies in education 13 education 1302 curriculum and pedagogy. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.; van Aalst, J.; Chan, C.K.K.; Tian, W. Reflective assessment in knowledge building by students with low academic achievement. Int. J. Comput. Support. Collab. Learn. 2016, 11, 281–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliott, C.; Mavriplis, C.; Anis, H. An entrepreneurship education and peer mentoring program for women in STEM: Mentors’ experiences and perceptions of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intent. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, L.; Eickman, L.; Byrne, C.E.; Fischer, S. Enhancing empowerment in eating disorder prevention: Another examination of the REbeL peer education model. Eat. Behav. 2017, 25, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kling, J.; Kwakkenbos, L.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Rumsey, N.; Frisen, A.; Brandao, M.P.; Silva, A.G.; Dooley, B.; Rodgers, R.F.; Fitzgerald, A. Systematic review of body image measures. Body Image 2019, 30, 170–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vartanian, L.R.; Hayward, L.E. Dimensions of internalization relevant to the identity disruption model of body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2020, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, L.; Eickman, L.; Byrne, C.E.; Fischer, S. REbeL peer education: A model of a voluntary, after-school program for eating disorder prevention. Eat. Behav. 2017, 25, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crush, E.A.; Frith, E.; Loprinzi, P.D. Experimental effects of acute exercise duration and exercise recovery on mood state. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 229, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmesser, L.; Verscheure, S. Are eating disorder prevention programs effective? J. Athl. Train. 2009, 44, 304–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgot-Borgen, C.; Friborg, O.; Kolle, E.; Torstveit, M.K.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Engen, K.M.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Pettersen, G.; Bratland-Sanda, S. Does the Healthy Body Image program improve lifestyle habits among high school students? a randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stice, E.; Andersson, G.; Persson, J.E. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of virtually delivered body project (vBP) groups to prevent eating disorders. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 643–656. [Google Scholar]

- Tirlea, L.; Truby, H.; Haines, T.P. Pragmatic, randomized controlled trials of the girls on the go! program to improve self-esteem in girls. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 30, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Gai, X.; Zhou, Y. A meta-analysis of media literacy interventions for deviant behaviors. Comput. Educ. 2019, 139, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, K.A.; Karunaratne, N.S.; Naidu, S.; Exintaris, B.; Short, J.L.; Wolcott, M.D.; Singleton, S.; White, P.J. Development of a self-report instrument for measuring in-class student engagement reveals that pretending to engage is a significant unrecognized problem. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruggieri, R.A.; Santoro, E.; De Caro, F.; Palmieri, L.; Capunzo, M.; Venuleo, C.; Boccia, G. Internet addiction: A prevention action-research intervention. Epidemiol. Biostat. Public Health 2016, 13, e11817-1–e11817-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eborall, H.C.; Dallosso, H.M.; Daly, H.; Martin-Stacey, L.; Heller, S.R. The face of equipoise-delivering a structured education programme within a randomized controlled trial: Qualitative study. Trials 2014, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D. Eating disorders prevention: Looking backward, moving forward; looking inward, moving outward. Eat. Disord. 2016, 24, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session Number | Topic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction | Introducing the program’s objectives and goals, forming the groups, discussing expectations, and establishing the group contract. |

| 2 | Self-care | Discussing sleeping and eating hygiene, exercise, sharing self-care experiences and outcomes. |

| 3 | Self-preservation | Discussing territorial issues, self-space, and territorial boundaries. |

| 4 | Media literacy | Exploring and recognizing advertisements’ tactics and their impact on ourselves and discussing ways to address media temptations. |

| 5 | Our feelings | Facilitating a “feeling differentiation” activity. Sharing and recognizing observed and hidden feelings. Discussing feelings management strategies. |

| 6 | Accepting appearance differences | Discussing the ideal appearance in comparison to their unrealistic and narrow construction. Learning strategies to avoid and challenge comparisons and that different look is not necessarily a bad thing. |

| 7 | Accepting our weaknesses | Discussing how people turn their defects into productive effects. Learning how to accept disadvantages or weaknesses that cannot be changed. |

| 8 | My body and I | Exploring the physical changes during adolescence and role-play management strategies. |

| 9 | Adolescence rights and responsibilities | Discussing how growing up makes us take different responsibilities and gaining more independence and rights. |

| 10 | Summary and commitment | Reviewing key messages. Committing to engaging in positive self-care and positive body-image behaviors and rejecting risk factors. |

| Comparison n = 33 | Intervention n = 33 | p-Value 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± standard deviation | 26.3 ± 1.4 | 26.2 ± 1.9 | 0.35 | |

| Gender, n (%) | Male | 5 (15.1) | 5 (15.1) | 1.0000 |

| Female | 28 (84.9) | 28 (84.9) | ||

| Parental status, n (%) | Living alone | 6 (18.2) | 5 (15.1) | 0.74 |

| Living in a relationship | 27 (81.8) | 28 (84.9) | ||

| Socioeconomic status 2, mean ± standard deviation, median | 0.9 ± 0.4, 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.2, 1.0 | 0.74 | |

| Comparison Group n = 33 | Intervention Group n = 33 | p Value | Cohen’s d 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | Mean | Std | |||

| Rosenberg | 29.82 | 4.80 | 32.36 | 3.86 | 0.0208 * | 0.58 |

| Body-esteem Total | 2.15 | 0.72 | 2.46 | 0.65 | 0.0736 | 0.45 |

| Body-esteem Appearance | 2.24 | 0.78 | 2.61 | 0.72 | 0.0483 * | 0.49 |

| Body-esteem Weight | 2.38 | 0.87 | 2.37 | 0.80 | 0.9863 | 0.01 |

| Body-esteem Attribution | 2.08 | 0.79 | 2.45 | 0.64 | 0.0404 * | 0.51 |

| SATAQ-4 media | 2.98 | 1.10 | 3.30 | 1.16 | 0.2690 | 0.28 |

| Self-care | 38.67 | 3.47 | 39.00 | 3.93 | 0.7161 | 0.09 |

| Comparison Group n = 33 | Intervention Group n = 33 | p Value (Effect Size 1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | Median | Mean | Std | Median | ||

| ADVER | 4.33 | 1.73 | 4.00 | 4.67 | 1.43 | 5.00 | 0.4645 (0.090) |

| EAT_26 | 10.00 | 11.40 | 6.00 | 11.82 | 8.05 | 10.00 | 0.0522 (0.239) |

| Comparison Group | Intervention Group | Effect | F (df) | Effect Size Marginal R2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Intervention | Follow-Up | Baseline | Post-Intervention | Follow-Up | |||||

| Rosenberg 1 | Mean | 29.82 | 30.08 | 31.4 | 32.36 | 33.42 | 33.88 | Group | 31.81 (1.63) *** | 0.072 |

| Std | 4.80 | 4.78 | 5.14 | 3.86 | 4.27 | 4.34 | Time | 4.94 (2.126) ** | ||

| n | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Group × Time | 0.48 (2.126) | ||

| Body-esteem Total | Mean | 2.15 | 2.25 | 2.39 | 2.46 | 2.63 | 2.65 | Group | 4.18 (1.64) * | 0.066 |

| Std | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.63 | Time | 6.61 (2.128) ** | ||

| n | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Group × Time | 0.51 (2.128) | ||

| Body-esteem Appearance 1 | Mean | 2.24 | 2.39 | 2.17 | 2.61 | 2.72 | 2.61 | Group | 0.60 (1.63) | 0.088 |

| Std | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.78 | Time | 6.13 (2.126) ** | ||

| n | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Group × Time | 0.36 (2.128) | ||

| Body-esteem Weight | Mean | 2.38 | 2.17 | 2.26 | 2.37 | 2.51 | 2.57 | Group | 1.25 (1.64) | 0.025 |

| Std | 0.87 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.79 | Time | 0.53 (2.128) | ||

| n | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Group × Time | 3.28 (2.128) * | ||

| Body-esteem Attribution | Mean | 2.08 | 2.02 | 2.31 | 2.45 | 2.62 | 2.68 | Group | 8.60 (1.64) ** | 0.115 |

| Std | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.69 | Time | 6.13 (2.128) ** | ||

| n | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Group × Time | 1.98 (2.128) | ||

| SATAQ-4 media | Mean | 2.98 | 3.20 | 3.11 | 3.30 | 2.95 | 3.08 | Group | 0.00 (1.64) | 0.011 |

| Std | 1.10 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.16 | 1.02 | 1.14 | Time | 0.17 (2.128) | ||

| n | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Group × Time | 3.28 (2.128) * | ||

| Self-care | Mean | 38.67 | 41.15 | 39.70 | 39.00 | 41.06 | 39.76 | Group | 0.03 (1.64) | 0.085 |

| Std | 3.47 | 2.87 | 3.04 | 3.93 | 2.66 | 2.36 | Time | 16.17 (2.128) *** | ||

| n | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | Group × Time | 0.14 (2.128) | ||

| Comparison Group n = 33 | Intervention Group n = 33 | p Value 1 (Effect Size) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | Median | p Value 2 (W) | Mean | Std | Median | p Value 2 (W) | |||

| ADVER | Baseline | 4.33 | 1.73 | 4.00 | 0.0020 (0.38) | 4.67 | 1.43 | 5.00 | <0.0001 (0.57) | 0.4645 (0.090) |

| Post-intervention | 4.30 | 1.63 | 5.00 | 5.64 | 1.54 | 6.00 | 0.0005 (0.431) | |||

| Follow-up | 5.12 | 1.19 | 5.00 | 5.79 | 1.49 | 6.00 | 0.0255 (0.275) | |||

| EAT-26 | Baseline | 10.00 | 11.40 | 6.00 | 0.0780 (0.15) | 11.82 | 8.05 | 10.00 | 0.0041 (0.33) | 0.0522 (0.239) |

| Post-intervention | 7.36 | 8.46 | 4.00 | 9.30 | 7.87 | 8.00 | 0.0656 (0.227) | |||

| Follow-up | 9.94 | 9.60 | 5.00 | 10.00 | 9.38 | 8.00 | 0.5586 (0.072) | |||

| Comparison Group n = 33 | Intervention Group n = 33 | Effect | Chi-Square (df) | Effect Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score > 20 | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| EAT-26 | Baseline | 5 | 15.15 | 5 | 15.15 | Group | 0.63 (1) | 0.027 |

| Post-intervention | 3 | 9.09 | 2 | 6.06 | Time | 7.17 (2) * | ||

| Follow-up | 6 | 18.18 | 2 | 6.06 | Group × Time | 3.16 (2) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golan, M.; Tzabari, D.; Mozeikov, M. The Impact of Delivering School-Based Wellness Programs for Emerging Adult Facilitators—A Quasi-Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074278

Golan M, Tzabari D, Mozeikov M. The Impact of Delivering School-Based Wellness Programs for Emerging Adult Facilitators—A Quasi-Controlled Clinical Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074278

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolan, Moria, Dana Tzabari, and Maya Mozeikov. 2022. "The Impact of Delivering School-Based Wellness Programs for Emerging Adult Facilitators—A Quasi-Controlled Clinical Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074278

APA StyleGolan, M., Tzabari, D., & Mozeikov, M. (2022). The Impact of Delivering School-Based Wellness Programs for Emerging Adult Facilitators—A Quasi-Controlled Clinical Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074278