Depression and Perceived Social Support among Unemployed Youths in China: Investigating the Roles of Emotion-Regulation Difficulties and Self-Efficacy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Aims

2.1. Depression and Perceived Social Support

2.2. Perceived Social Support, Emotion-Regulation Difficulties, Self-Efficacy, and Depression

2.3. Research Aims and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Process

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.2.1. Demographics

3.2.2. Perceived Social Support

3.2.3. Depression

3.2.4. Emotion-Regulation Difficulties

3.2.5. Self-Efficacy

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Statistics

4.2. Depression Prevalence

4.3. Correlations between Variables

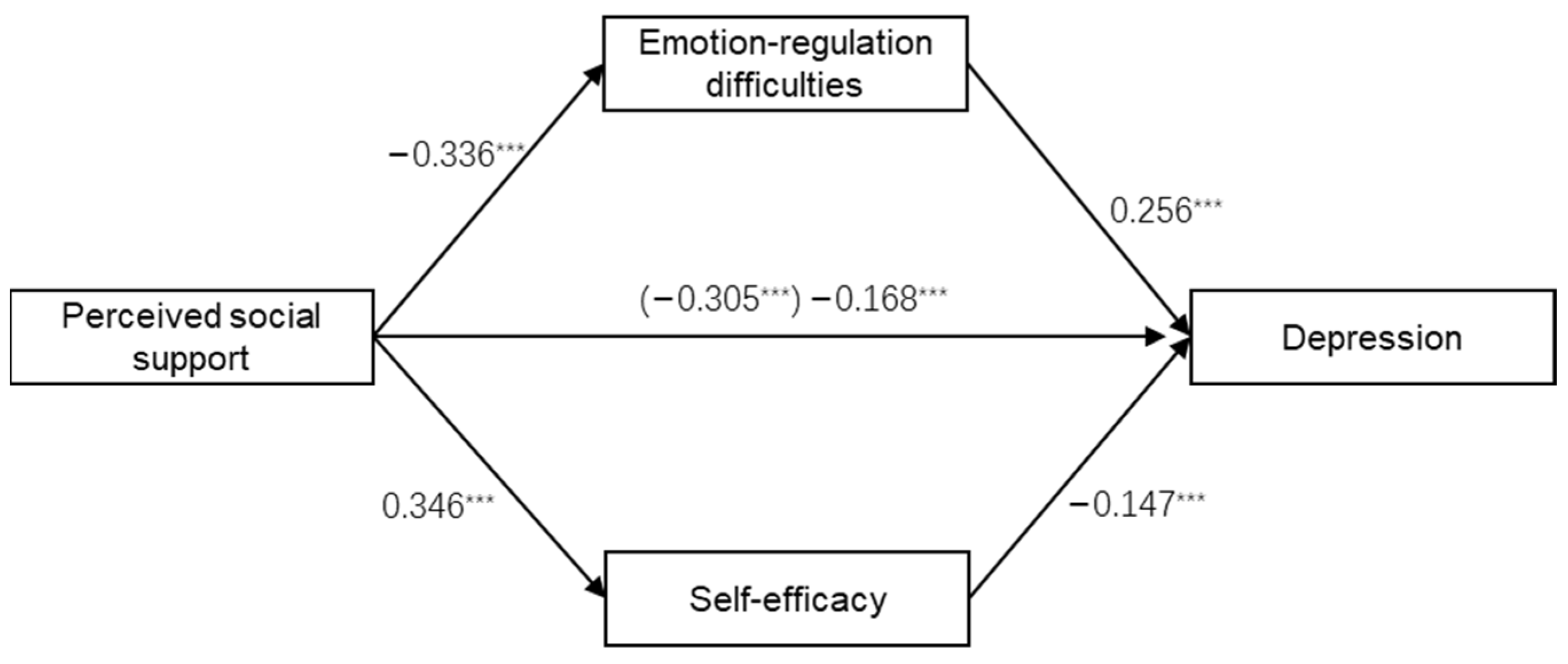

4.4. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_737648/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- The Ministry of Education of China. The Initial Employment Rate of College Graduates in China Has Exceeded 77% for Many Years. 2020. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/fbh/live/2020/52692/mtbd/202012/t20201202_502835.html (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- China’s National Statistics Bureau. Urban Surveyed Unemployment Rate. 2021. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=A01 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- China’s National Statistics Bureau. China Statistical Yearbook 2021. 2021. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexch.htm (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Dooley, D.; Fielding, J.; Levi, L. Health and unemployment. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1996, 17, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, K.A.; Jolly, N.A.; Placzek, D.W. Earnings losses of displaced workers and the business cycle: An analysis with ad-ministrative data. Econ. Lett. 2011, 111, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tøge, A.G. Health effects of unemployment in Europe (2008–2011): A longitudinal analysis of income and financial strain as mediating factors. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Griffiths, R.F.; Gavin, M.B. Time structure and unemployment: A longitudinal investigation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P.A.; Macintyre, S.R. The relative effects of deprivation of the latent and manifest benefits of employment on the well-being of unemployed people. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, M.W.; Sandifer, R.; Stein, S. Effects of unemployment on mental and physical health. Am. J. Public Health 1985, 75, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korpi, T. Accumulating Disadvantage. Longitudinal Analyses of Unemployment and Physical Health in Representative Samples of the Swedish Population. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2001, 17, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKee-Ryan, F.M.; Song, Z.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kinicki, A.J. Psychological and Physical Well-Being During Unemployment: A Meta-Analytic Study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strully, K.W. Job loss and health in the U.S. labor market. Demography 2009, 46, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Lieberman, M.A.; Menaghan, E.G.; Mullan, J.T. The stress process. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1982, 22, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Hoppe, S. Attributions for Job Termination and Psychological Distress. Hum. Relat. 1994, 47, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, L.; Extremera, N.; Peláez-Fernández, M.A. Linking Social Support to Psychological Distress in the Unemployed: The Moderating Role of Core Self-Evaluations. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 127, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.H.; Choi, J.N.; Vinokur, A.D. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: How financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, S.A.; Brand, J.E.; House, J.S. Toward a Better Estimation of the Effect of Job Loss on Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, W.T.; Bradley, E.; Dubin, J.A.; Jones, R.N.; Falba, T.A.; Teng, H.; Kasl, S.V. The Persistence of Depressive Symptoms in Older Workers Who Experience Involuntary Job Loss: Results from the Health and Retirement Survey. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, S221–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darity, W.; Goldsmith, A.H. Social psychology, unemployment, and macroeconomics. J. Econ. Perspect. 1996, 10, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, D.; Catalano, R.; Wilson, G. Depression and unemployment: Panel findings from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1994, 22, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Knesebeck, O. Perceived job insecurity, unemployment and depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Depression: Fact Sheet. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Paul, K.I.; Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, F.; Gayet, C. Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 40, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebok, G.W.; Bradshaw, C.; Volk, H.; Mendelson, T.; Eaton, W.; Letourneau, E.; Kellam, S. Models of stress and adapting to risk: A life course, developmental perspective. In Public Mental Health; Eaton, W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 285–322. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, R.E.; Thompson, N.J. Unemployment and Depression Among Emerging Adults in 12 States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2010. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.O.; Jones, T.M.; Yoon, Y.; Hackman, D.A.; Yoo, J.P.; Kosterman, R. Young Adult Unemployment and Later Depression and Anxiety: Does Childhood Neighborhood Matter? J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reneflot, A.; Evensen, M. Unemployment and psychological distress among young adults in the Nordic countries: A review of the literature. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2014, 23, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.D.; Huang, X.Y.; Fox, K.R.; Franklin, J.C. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliffe, S.; Tai, S.S.; Haines, A.; Booroff, A.; Goldenberg, E.; Morgan, P.; Gallivan, S. Assessment of elderly people in general practice. 4. Depression, functional ability and contact with services. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1993, 43, 371–374. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri, L.N.; Awerbuch, A.W.; Jarskog, L.F.; Penn, D.L.; Pinkham, A.; Harvey, P.D. Depression predicts self assessment of social function in both patients with schizophrenia and healthy people. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokur, A.D.; Schul, Y. The web of coping resources and pathways to reemployment following a job loss. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R. The Individual Experience of Unemployment. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 63, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Kou, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.F.; Wen, Z.P.; Li, Q.; Chen, B.; Weng, W.J. Factors influencing cognitive reactivity among young adults at high risk for depression in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaras, E.; Jaureguizar, J.; Garaigordobil, M. Child and Adolescent Depression: A Review of Theories, Evaluation Instruments, Prevention Programs, and Treatments. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindert, J.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Grashow, R.; Gal, G.; Braehler, E.; Weisskopf, M.G. Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2014, 59, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohafza, H.R.; Afshar, H.; Keshteli, A.H.; Mohammadi, N.; Feizi, A.; Taslimi, M.; Adibi, P. What's the role of perceived social support and coping styles in depression and anxiety? J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 944–949. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, M.G.; Cohen, J.L.; Lucas, T.; Baltes, B.B. The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, H.; Wei, X.; Yin, J.; Liang, P.; Zhang, H.; Kou, L.; Hao, M.; You, L.; Li, X.; et al. Reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Chinese mainland patients with methadone maintenance treatment. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, K.; Soenens, B.; Van Petegem, S.; Vansteenkiste, M. Perceived Maternal Autonomy Support and Early Adolescent Emotion Regulation: A Longitudinal Study. Soc. Dev. 2015, 24, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lilympaki, I.; Makri, A.; Vlantousi, K.; Koutelekos, I.; Babatsikou, F.; Polikandrioti, M. Effect of Perceived Social Support on the Levels of Anxiety and Depression of Hemodialysis Patients. Mater. Socio Med. 2016, 28, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gündüz, N.; Üşen, A.; Aydin Atar, E. The Impact of Perceived Social Support on Anxiety, Depression and Severity of Pain and Burnout Among Turkish Females with Fibromyalgia. Arch. Rheumatol. 2018, 34, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, D.; Teng, M.; Xu, D. Impact of perceived social support on depression in Chinese rural-to-urban migrants: The mediating effects of loneliness and resilience. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 1603–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, E.; Aşti, T. Determine the relationship between perceived social support and depression level of patients with diabetic foot. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2015, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Von Cheong, E.; Sinnott, C.; Dahly, D.; Kearney, P.M. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and later-life depression: Perceived social support as a potential protective factor. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxman, T.E.; Berkman, L.F.; Kasl, S.; Freeman, D.H.; Barrett, J. Social Support and Depressive Symptoms in the Elderly. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 135, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Väänänen, J.-M.; Marttunen, M.; Helminen, M.; Kaltiala-Heino, R. Low perceived social support predicts later depression but not social phobia in middle adolescence. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, A.; Beihai, T.; Abbas, N.; Ali, S.; Yao, W.; Imran, M. Role of Perceived Social Support on the Association between Physical Disability and Symptoms of Depression in Senior Citizens of Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wade, T.D.; Kendler, K.S. The Relationship between Social Support and Major Depression: Cross-sectional, longitudinal, and genetic perspectives. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2000, 188, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, W.L.; Medland, S.E.; Wray, N.R.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Heath, A.C.; Byrne, B. Phenotypic and Discordant-Monozygotic Analyses of Stress and Perceived Social Support as Antecedents to or Sequelae of Risk for Depression. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2009, 12, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kopp, C.B. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Dev. Psychol. 1989, 25, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P.W.; Spears, F.M. Emotion Regulation in Low-income Preschoolers. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, M.; Schmoeger, M.; Auff, E.; Willinger, U. Subjective emotional arousal: An explorative study on the role of gender, age, intensity, emotion regulation difficulties, depression and anxiety symptoms, and meta-emotion. Psychol. Res. 2020, 84, 1857–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and Unhealthy Emotion Regulation: Personality Processes, Individual Differences, and Life Span Development. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S.V.; Rostain, A.L.; Blader, J.; Busch, B.; Childress, A.C.; Connor, D.F.; Newcorn, J.H. Practitioner Review: Emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—Implications for clinical recognition and intervention. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Wilson, K.G.; Gifford, E.V.; Follette, V.M.; Strosahl, K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 1152–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennin, D.S.; Heimberg, R.G.; Turk, C.L.; Fresco, D.M. Applying an emotion regulation framework to integrative ap-proaches to generalized anxiety disorder. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 9, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.Y.; Thompson, R.J. Selection and implementation of emotion regulation strategies in major depressive disorder: An integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visted, E.; Vøllestad, J.; Nielsen, M.B.; Schanche, E. Emotion Regulation in Current and Remitted Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welkie, J.; Babinski, D.E.; Neely, K.A. Sex and Emotion Regulation Difficulties Contribute to Depression in Young Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visted, E.; Sørensen, L.; Vøllestad, J.; Osnes, B.; Svendsen, J.L.; Jentschke, S.; Binder, P.-E.; Schanche, E. The Association Between Juvenile Onset of Depression and Emotion Regulation Difficulties. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solbakken, O.A.; Ebrahimi, O.V.; Hoffart, A.; Monsen, J.T.; Johnson, S.U. Emotion regulation difficulties and interpersonal problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: Predicting anxiety and depression. Psychol. Med. 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Thompson, R.A. Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- English, T.; Lee, I.A.; John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation strategy selection in daily life: The role of social context and goals. Motiv. Emot. 2017, 41, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, C.J.; Fehling, K.B.; Selby, E.A. Sexual Minority Status and Psychological Risk for Suicide Attempt: A Serial Multiple Mediation Model of Social Support and Emotion Regulation. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izaguirre, L.A.; Fernández, A.R.; Palacios, E.G. Adolescent Life Satisfaction Explained by Social Support, Emotion Regulation, and Resilience. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 694183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, A.; Espinoza, M.; Boudesseul, J.; Heimark, K. Venezuelan Forced Migration to Peru During Sociopolitical Crisis: An Analysis of Perceived Social Support and Emotion Regulation Strategies. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2021, 32, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, P.K.; Prigerson, H.G.; Mazure, C.M. Self-efficacy as a mediator between stressful life events and depressive symptoms. Differences based on history of prior depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, E.J.; Merluzzi, T.V.; Zhang, Z.; Heitzmann, C.A. Depression and cancer survivorship: Importance of coping self-efficacy in post-treatment survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaksen, T.; Grimholt, T.K.; Skogstad, L.; Lerdal, A.; Ekeberg, Ø.; Heir, T.; Schou-Bredal, I. Self-diagnosed depression in the Norwegian general population—Associations with neuroticism, extraversion, optimism, and general self-efficacy. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenella, K.; Steffen, A.M. Self-reassurance and self-efficacy for controlling upsetting thoughts predict depression, anxiety, and perceived stress in help-seeking female family caregivers. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 32, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qiu, N.; Chen, C.; Wang, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhai, L. Self-Efficacy and Depression in Boxers: A Mediation Model. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 00791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Wang, S.; Qian, H.-Z.; Ruan, Y.; Amico, K.R.; Vermund, S.H.; Yin, L.; Qiu, X.; Zheng, S. Negative associations between general self-efficacy and anxiety/depression among newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in Beijing, China. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Kohan, S.; Farzi, S.; Khosravi, M.; Heidari, Z. The effect of pregnancy training classes based on Bandura self-efficacy theory on postpartum depression and anxiety and type of delivery. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G.; Côté, J.; Naccache, H.; Lambert, L.; Trottier, S. Prediction of adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A one-year lon-gitudinal study. AIDS Care 2005, 17, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, L.; Brouwer, J.; Jansen, E.; Crayen, C.; Hannover, B. Academic self-efficacy, growth mindsets, and university students' integration in academic and social support networks. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 62, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.I.; Alhebshi, S.; Elmi, F.; Bataineh, M.F. Perceived social support and self-efficacy beliefs for healthy eating and physical activity among Arabic-speaking university students: Adaptation and implementation of health beliefs survey questionnaire. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, M.D. It’s the quality not the quantity of ties that matters: Social networks and self-efficacy beliefs. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 53, 227–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turan, B.; Fazeli, P.L.; Raper, J.L.; Mugavero, M.J.; Johnson, M.O. Social support and moment-to-moment changes in treatment self-efficacy in men living with HIV: Psychosocial moderators and clinical outcomes. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orejudo, S.; Zarza-Alzugaray, F.J.; Casanova, O.; McPherson, G.E. Social Support as a Facilitator of Musical Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; She, R.; Gu, J.; Hao, C.; Hou, F.; Wei, D.; Li, J. The mediating role of self-stigma and self-efficacy between intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization and depression among men who have sex with men in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hussmanns, R. Measurement of employment, unemployment and underemployment—Current international standards and issues in their application. Bull. Labour Stat. 1985, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, K.; Li, H.; Wei, X.; Yin, J.; Liang, P.; Zhang, H.; Kou, L.; Hao, M.; You, L.; Li, X.; et al. Relationships between received and perceived social support and health-related quality of life among patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment in Mainland China. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2017, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, F.; Xi, S.; Niu, L.; Tebes, J.K.; Xiao, S.; Yu, Y. Psychometric Properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) Among Family Caregivers of People with Schizophrenia in China. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.; Brown, G.; Steer, R. Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II); The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Gong, Y.-H.; Wen, X.-P.; Guan, C.-P.; Li, M.-C.; Yin, P.; Wang, Z.-Q. Social Determinants of Health and Depression: A Preliminary Investigation from Rural China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xin, T. The Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II With Middle School Teachers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 548965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjureberg, J.; Ljótsson, B.; Tull, M.T.; Hedman, E.; Sahlin, H.; Lundh, L.-G.; Bjärehed, J.; DiLillo, D.; Messmanmoore, T.; Gumpert, C.H.; et al. Development and Validation of a Brief Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: The DERS-16. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2016, 38, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skutch, J.M.; Wang, S.B.; Buqo, T.; Haynos, A.F.; Papa, A. Which Brief Is Best? Clarifying the Use of Three Brief Versions of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2019, 41, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechler, J.; Lindqvist, K.; Falkenström, F.; Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G.; Philips, B. Emotion Regulation as a Time-Invariant and Time-Varying Covariate Predicts Outcome in an Internet-Based Psychodynamic Treatment Targeting Adolescent Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Fan, F. Sleep Reactivity and Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese Female Student Nurses: A Longitudinal Mediation Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 748064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, R.; Born, A. Optimistic self-beliefs: Assessment of general perceived self-efficacy in thirteen cultures. World Psychol. 1997, 3, 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.K.; Hu, Z.F.; Liu, Y. Evidences for reliability and validity of the Chinese version of general self-efficacy scale. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 7, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qi, H.; Liu, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, W.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Wang, G.; Xiang, Y.-T. Depression, anxiety and associated factors among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: A comparison of two cross-sectional studies. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-J.; Wang, L.-L.; Qi, M.; Yang, X.-J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Zhang, L.-G.; Yang, R.; Chen, J.-X. Depression, Anxiety, and Suicidal Ideation in Chinese University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 669833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombs, B.D.; Kwakkenbos, L.; Levis, A.W.; Benedetti, A. Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2018, 190, E44–E49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Li, W.; He, J.; Wu, L.; Yan, Z.; Tang, W. Mental health, duration of unemployment, and coping strategy: A cross-sectional study of unemployed migrant workers in eastern China during the economic crisis. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hom, M.A.; Stanley, I.H.; Rogers, M.L.; Tzoneva, M.; Bernert, R.A.; Joiner, T.E. The Association between Sleep Disturbances and Depression among Firefighters: Emotion Dysregulation as an Explanatory Factor. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schierholz, A.; Krüger, A.; Barenbrügge, J.; Ehring, T. What mediates the link between childhood maltreatment and depression? The role of emotion dysregulation, attachment, and attributional style. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2016, 7, 32652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, T.; Cross, D.; Powers, A.; Bradley, B. Emotion dysregulation as a mediator between childhood emotional abuse and current depression in a low-income African-American sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2014, 38, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michopoulos, V.; Powers, A.; Moore, C.; Villarreal, S.; Ressler, K.J.; Bradley, B. The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression on the relationship between childhood trauma exposure and emotional eating. Appetite 2015, 91, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krause, E.D.; Mendelson, T.; Lynch, T.R. Childhood emotional invalidation and adult psychological distress: The mediating role of emotional inhibition. Child Abuse Negl. 2003, 27, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between Big five personality and depressive symptoms among Chinese unemployed population: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cong, L.; Ju, Y.; Gui, L.; Zhang, B.; Ding, F.; Zou, C. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in Sleep Disorder and Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese Caregivers of Stroke Inpatients: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 3635–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, L.P. A self-control model of depression. Behav. Ther. 1977, 8, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benight, C.C.; Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 1129–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | % | N | BDI-II ≥ 14 (n = 252) | Depression Prevalence (row%) | p (Chi-Squared Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 61.4 | 314 | 150 | 47.8 | 0.378 |

| Female | 38.6 | 197 | 102 | 51.8 | |

| Age | |||||

| 16–19 | 21.1 | 108 | 49 | 45.4 | 0.356 |

| 20–24 | 78.9 | 403 | 203 | 50.4 | |

| Education | |||||

| Primary school and below | 1.2 | 6 | 3 | 50.0 | 0.972 |

| Junior high school | 20.9 | 107 | 51 | 47.7 | |

| Senior high school (including secondary vocational school) | 40.1 | 205 | 99 | 48.3 | |

| College | 36.2 | 185 | 95 | 51.4 | |

| Graduate school | 1.6 | 8 | 4 | 50.0 | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Unmarried | 87.3 | 446 | 221 | 49.6 | 0.552 |

| Married | 12.5 | 64 | 30 | 46.9 | |

| Divorced or others | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | |

| Place of household registration | |||||

| Shanghai | 75.3 | 385 | 191 | 49.6 | 0.815 |

| Non-Shanghai | 24.7 | 126 | 61 | 48.4 | |

| Duration of unemployment | |||||

| 1 month < ~ ≤ 3 months | 8.0 | 41 | 24 | 58.5 | 0.337 |

| 3 months < ~ ≤ 6 months | 15.9 | 81 | 43 | 53.1 | |

| 6 months < ~ ≤ 12 months | 22.5 | 115 | 61 | 53.0 | |

| 12 months < ~ ≤ 36 months | 37.6 | 192 | 85 | 44.3 | |

| >36 months | 16.0 | 82 | 39 | 47.6 | |

| Unemployment registration | |||||

| Registered | 27.6 | 141 | 76 | 53.9 | 0.201 |

| Not registered | 72.4 | 370 | 176 | 47.6 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSS | 1 | 46.69 | 14.85 | 16 | 82 | 12–84 | |||

| 2. ERD | −0.336 | 1 | 50.85 | 7.99 | 26 | 74 | 16–80 | ||

| 3. Self-efficacy | 0.346 | −0.168 | 1 | 26.96 | 5.76 | 12 | 40 | 10–40 | |

| 4. Depression | −0.305 | 0.337 | −0.248 | 1 | 14.19 | 8.26 | 0 | 48 | 0–63 |

| No. | Pathways | Effect Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| 1 | PSS–RED–depression | −0.0478 | −0.0691 | −0.0303 |

| 2 | PSS–self-efficacy–depression | −0.0284 | −0.0459 | −0.0124 |

| 3 | PSS–depression (Direct effect) | −0.0936 | −0.1429 | −0.0443 |

| 4 | Total effect | −0.1698 | −0.2160 | −0.1237 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hua, Z.; Ma, D. Depression and Perceived Social Support among Unemployed Youths in China: Investigating the Roles of Emotion-Regulation Difficulties and Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084676

Hua Z, Ma D. Depression and Perceived Social Support among Unemployed Youths in China: Investigating the Roles of Emotion-Regulation Difficulties and Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084676

Chicago/Turabian StyleHua, Zhiya, and Dandan Ma. 2022. "Depression and Perceived Social Support among Unemployed Youths in China: Investigating the Roles of Emotion-Regulation Difficulties and Self-Efficacy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084676