Seeking Causality in the Links between Time Perspectives and Gratitude, Savoring the Moment and Prioritizing Positivity: Initial Empirical Test of Three Conceptual Models

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Time Perspectives

1.2. Well-Being and Well-Being Boosters

1.3. Linking Time Perspectives, Well-Being Boosters, and Subjective Well-Being

1.3.1. Trait-Behavior Model

1.3.2. Accumulation Model

1.3.3. Feedback-Loop Model

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

Subjective Well-Being

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Correlations

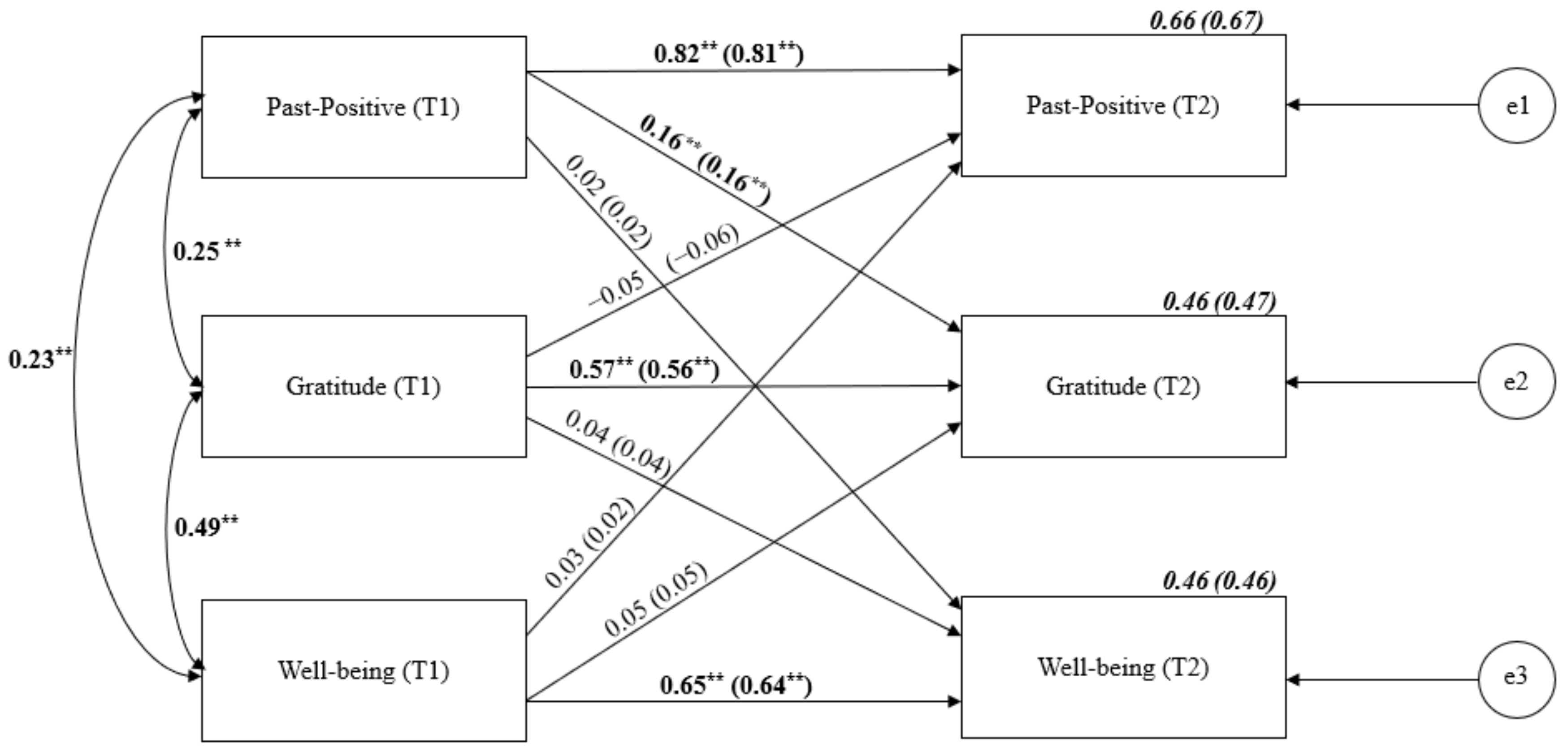

3.3. Cross-Lagged Panel Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | ddep | ||

| 1 | Past-Negative | 2.88 | 0.75 | 2.80 | 0.69 | 2.57 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| 2 | Past-Positive | 3.58 | 0.63 | 3.56 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.45 | 0.03 |

| 3 | Present-Fatalistic | 2.42 | 0.60 | 2.48 | 0.57 | −1.77 | 0.08 | −0.09 |

| 4 | Present-Hedonistic | 3.24 | 0.52 | 3.19 | 0.51 | 2.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| 5 | Future-Negative | 3.04 | 0.56 | 3.04 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 0.91 | 0.01 |

| 6 | Future-Positive | 3.65 | 0.51 | 3.66 | 0.52 | −0.73 | 0.46 | −0.03 |

| 7 | Gratitude | 5.54 | 0.98 | 5.47 | 0.94 | 1.30 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| 8 | Savoring | 4.77 | 1.10 | 4.80 | 1.05 | −0.57 | 0.57 | −0.03 |

| 9 | Prioritizing positivity | 7.01 | 1.54 | 7.02 | 1.40 | −0.11 | 0.91 | −0.01 |

| 10 | Well-being | 5.35 | 1.88 | 5.14 | 0.82 | 2.03 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

Appendix B

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | dindep | ||

| 1 | Past-Negative | 2.88 | 0.75 | 2.99 | 0.84 | −1.46 | 0.15 | −0.14 |

| 2 | Past-Positive | 3.58 | 0.63 | 3.44 | 0.73 | 2.27 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| 3 | Present-Fatalistic | 2.42 | 0.60 | 2.55 | 0.66 | −2.17 | 0.03 | −0.21 |

| 4 | Present-Hedonistic | 3.24 | 0.52 | 3.33 | 0.53 | −1.82 | 0.07 | −0.17 |

| 5 | Future-Negative | 3.04 | 0.56 | 3.11 | 0.63 | −1.21 | 0.23 | −0.11 |

| 6 | Future-Positive | 3.65 | 0.51 | 3.52 | 0.57 | 2.46 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| 7 | Gratitude | 5.54 | 0.98 | 5.43 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 0.25 | 0.11 |

| 8 | Savoring | 4.77 | 1.10 | 4.73 | 1.25 | 0.38 | 0.71 | 0.04 |

| 9 | Prioritizing positivity | 7.01 | 1.54 | 7.28 | 1.32 | −2.00 | 0.05 | −0.19 |

| 10 | Well-being | 5.35 | 1.88 | 4.95 | 2.29 | −2.04 | <0.01 | −0.19 |

References

- Zimbardo, P.G.; Boyd, J.N. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M.; Fieulaine, N.; Zimbardo, P.G. Putting time in a wider perspective: The past, the present, and the future of time perspective theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 592–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunningham, K.F.; Zhang, J.W.; Howell, R.T. Time perspectives and subjective well-being: A dual-pathway framework. In Time Perspective Theory: Review, Research and Application; Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., van Beek, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Siu, P.M. Unraveling the direct and indirect effects between future time perspective and subjective well-being across adulthood. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burzynska, B.; Stolarski, M. Rethinking the Relationships Between Time Perspectives and Well-Being: Four Hypothetical Models Conceptualizing the Dynamic Interplay Between Temporal Framing and Mechanisms Boosting Mental Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzynska-Tatjewska, B.; Stolarski, M.; Matthews, G. Do time perspectives moderate the effects of gratitude, savoring and prioritizing positivity on well-being? A test of the temporal match-mismatch model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 189, 111501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Field Theory in the Social Sciences: Selected Theoretical Papers; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo, P.G.; Boyd, J.N. The Time Paradox—The New Psychology of Time That Will Change Your Life; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vowinckel, J.C.; Westerhof, G.J.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Webster, J.D. Flourishing in the now: Initial validation of a present-eudaimonic time perspective scale. Time Soc. 2017, 26, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol-Kwapinska, M. Hedonism, fatalism and ‘carpe diem’: Profiles of attitudes towards the present time. Time Soc. 2013, 22, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carelli, M.G.; Wiberg, B.; Wiberg, M. Development and construct validation of the swedish zimbardo time perspective inventory. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 27, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Howell, R.T.; Stolarski, M. Comparing three methods to measure a balanced time perspective: The relationship between a balanced time perspective and subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Howell, R.T. Do time perspectives predict unique variance in life satisfaction beyond personality traits? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M.; Matthews, G. Time perspectives predict mood states and satisfaction with life over and above personality. Curr. Psychol. 2016, 35, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Shmotkin, D.; Ryff, C.D. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M. Authentic Happiness; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Layous, K. How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J.A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Froh, J.J.; Geraghty, A.W.A. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiorka, A.; Sobol-Kwapinska, M. People with a positive time perspective are more grateful and happier: Gratitude mediates the relationship between time perspective and life satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhullar, N.; Surman, G.; Schutte, N. Dispositional gratitude mediates the relationship between a past-positive temporal frame and well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, F.B. Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI): A scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. J. Ment. Health 2003, 12, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoidbach, J.; Berry, E.V.; Hansenne, M.; Mikolajczak, M. Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Klibert, J.J.; Tarantino, N.; Lamis, D.A. Savoring and self-compassion as protective factors for depression. Stress Health 2017, 33, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalino, L.I.; Algoe, S.B.; Fredrickson, B.L. Prioritizing positivity: An effective approach to pursuing happiness? Emotion 2014, 14, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Ittersum, K. The effect of decision makers’ time perspective on intention–behavior consistency. Mark. Lett. 2012, 23, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghielen, S.T.S.; van Woerkom, M.; Meyers, C.M. Promoting positive outcomes through strengths interventions: A literature review. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Set like plaster? Evidence for the stability of adult personality. In Can Personality Change? Heatherton, T.F., Weinberger, J.L., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W.; Hopwood, C.J.; Back, M.D.; Denissen, J.J.; Hennecke, M.; Hill, P.L.; Zimmermann, J. Personality trait stability and change. Personal. Sci. 2021, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W. Grateful people are happier because they have fond memories of their past. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; King, R.B. Prioritizing positivity optimizes positive tendency emotions and life satisfaction: A three-wave longitudinal study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 96, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Kim, S.; Pitts, M.J. Promoting subjective well-being through communication savoring. Commun. Q. 2021, 69, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, P.J.; Morey, J.N.; Segerstrom, S.C. Beliefs about savoring in older adulthood: Aging and perceived health affect temporal components of perceived savoring ability. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 105, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, J.L.; Bryant, F.B. Savoring and well-being: Mapping the cognitive-emotional terrain of the happy mind. In The Happy Mind: Cognitive Contributions to Well-Being; Robinson, M.D., Eid, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansenne, M. Valuing Happiness is Not a Good Way of Pursuing Happiness, but Prioritizing Positivity is: A Replication Study. Psychol. Belg. 2021, 61, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robustelli, B.L.; Whisman, M.A. Gratitude and life satisfaction in the United States and Japan. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu-Gherasim, L.R.; Mardari, C.R.; Măirean, C. The relation between time perspectives and well-being: A meta-analysis on research. Curr. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochemczyk, Ł.; Pietrzak, J.; Buczkowski, R.; Stolarski, M.; Markiewicz, Ł. You only live once: Present-hedonistic time perspective predicts risk propensity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 115, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossakowska, M.; Kwiatek, P. Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do badania wdzięczności GQ-6 [The polish adaptation of the gratitude questionnaire (GQ-6)]. Przegl. Psychol. 2014, 57, 501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Catalino, L.I.; Boulton, A.J. The psychometric properties of the prioritizing positivity scale. J. Personal. Assess. 2021, 103, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busseri, M.A.; Sadava, S.W. A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, K.S. Is the shift in chronotype associated with an alternation in well-being? Biol. Rhythm Res. 2015, 46, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.W. Cross lagged panel analysis. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Allen, M.R., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 313–314. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, M.; Grajewski, P.; Shevlin, M. Adjustment disorder, traumatic stress, depression and anxiety in Poland during an early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1860356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harber, K.D.; Zimbardo, P.G.; Boyd, J.N. Participant self-selection biases as a function of individual differences in time perspective. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M.; Witowska, J. Balancing One’s Own Time Perspective from Aerial View: Metacognitive Processes in Temporal Framing. In Time Perspective; Kostić, A., Chadee, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, J.R.; Brase, G.L. Taking time to be healthy: Predicting health behaviors with delay discounting and time perspective. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M.T.; Perry, J.L.; Cole, J.C.; Worrell, F.C. What time is it? Temporal psychology measures relate differently to alcohol-related health outcomes. Addict. Res. Theory 2018, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M.; Matthews, G.; Postek, S.; Zimbardo, P.G.; Bitner, J. How we feel is a matter of time: Relationships between time perspective and mood. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019): Situation Report-54. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331478 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Maison, D.; Jaworska, D.; Adamczyk, D.; Affeltowicz, D. The challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and the way people deal with them. A qualitative longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Seydavi, M.; Zamani, E. The mediating role of personalized psychological flexibility in the association between distress intolerance and psychological distress: A national survey during the fourth wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Rudolph, C.W. Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Sevenius Nilsen, T.; Knapstad, M.; Skirbekk, V.; Skogen, J.; Vedaa, Ø.; Nes, R.B. Covid-fatigued? A longitudinal study of Norwegian older adults’ psychosocial well-being before and during early and later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Ageing 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmyter, F.; De Raedt, R. The relationship between time perspective and subjective well-being of older adults. Psychol. Belg. 2012, 52, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tseferidi, S.-I.; Griva, F.; Anagnostopoulos, F. Time to get happy: Associations of time perspective with indicators of well-being. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positivity: Groundbreaking Research to Release Your Inner Optimistic and Thrive; Oneworld: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, R.; Lau, E.N. Is Mindfulness Linked to Life Satisfaction? Testing Savoring Positive Experiences and Gratitude as Mediators. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 591103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwin, D.F.; Campbell, R.T. Quantitative approaches. Longitudinal methods in the study of human development and aging. In Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences, 5th ed.; Binstock, R.H., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łowicki, P.; Witowska, J.; Zajenkowski, M.; Stolarski, M. Time to believe: Disentangling the complex associations between time perspective and religiosity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 134, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlah, J.; Zieba, M. Prioritizing Positivity Scale: Psychometric Properties of the Polish Adaptation (PPS-PL). Ann. Psychol. 2021, 24, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits. In The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment; Boyle, G.J., Matthews, G., Saklofske, D.H., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairys, A.; Liniauskaite, A. Time perspective and personality. In Time Perspective Theory: Review, Research and Application; Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., van Beek, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Stolarski, M.; Ledzińska, M.; Matthews, G. Morning is tomorrow, evening is today: Relationships between chronotype and time perspective. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2013, 44, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.; Stolarski, M. Emotional processes in development and dynamics of individual time perspective. In Time Perspective Theory: Review, Research and Application; Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., van Beek, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, A.; Papastamatelou, J.; Vowinckel, J.; Klamut, O.; Heger, A. Time Is the Fire in Which We Burn (Out): How Time Perspectives Affect Burnout Tendencies in Health Care Professionals Via Perceived Stress and Self-Efficacy. Psychol. Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel-Fitzgerald, C.; Millstein, R.A.; von Hippel, C.; Howe, C.J.; Tomasso, L.P.; Wagner, G.R.; VanderWeele, T.J. Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate? Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deary, I.J.; Weiss, A.; Batty, G.D. Intelligence and personality as predictors of illness and death: How researchers in differential psychology and chronic disease epidemiology are collaborating to understand and address health inequalities. Psychol. Sci. Publ. Int. 2010, 11, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, C. Appreciating gratitude: Can gratitude be used as a psychological intervention to improve individual well-being? Couns. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Past-Negative (1) | 2.88 | 0.75 | 0.84 | - | −0.35 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.08 | 0.56 ** | −0.14 * | −0.36 ** | −0.49 ** | −0.16 * | −0.63 ** | 0.78 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.06 | 0.46 ** | 0.17 * | −0.25 ** | −0.47 ** | −0.09 | −0.50 ** |

| 2 | Past-Positive (1) | 3.58 | 0.63 | 0.76 | −0.37 ** | - | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.15 * | 0.09 | 0.38 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.37 ** | −0.30 ** | 0.80 ** | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.15 | 0.39 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.27 ** |

| 3 | Present-Fatalistic (1) | 2.42 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.39 ** | −0.06 | - | 0.32 ** | 0.43 ** | −0.47 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.22 ** | 0.07 | −0.36 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.10 | 0.71 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.27 ** | 0.02 | −0.37 ** |

| 4 | Present-Hedonistic (1) | 3.24 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.33 ** | - | −0.02 | −0.36 ** | 0.11 | 0.14 * | 0.32 ** | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.26 ** | 0.72 ** | −0.01 | −0.35 ** | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.23 ** | −0.03 |

| 5 | Future-Negative (1) | 3.04 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.56 ** | −0.16 * | 0.42 ** | 0.00 | - | −0.08 | −0.30 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.14 * | −0.51 ** | 0.42 ** | −0.07 | 0.30 ** | −0.01 | 0.68 ** | 0.00 | −0.16 * | −0.41 ** | −0.08 | −0.37 ** |

| 6 | Future-Positive (1) | 3.65 | 0.51 | 0.73 | −0.15 * | 0.12 | −0.44 ** | −0.32 ** | −0.08 | - | 0.21 ** | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.22 ** | −0.17 * | 0.08 | −0.33 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.08 | 0.78 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.24 ** |

| 7 | Gratitude (1) | 5.54 | 0.98 | 0.79 | −0.38 ** | 0.41 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.14 * | −0.30 ** | 0.23 ** | - | 0.43 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.54 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.00 | −0.21 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.39 ** |

| 8 | Savoring (1) | 4.77 | 1.10 | 0.85 | −0.50 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.15 * | −0.48 ** | 0.03 | 0.45 ** | - | 0.37 ** | 0.58 ** | −0.38 ** | 0.23n ** | −0.15 * | 0.11 | −0.34 ** | 0.01 | 0.25 ** | 0.78 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.42 ** |

| 9 | Prioritizing positivity (1) | 7.01 | 1.54 | 0.85 | −0.15 * | 0.26 ** | 0.07 | 0.34 ** | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.33 ** | 0.36 ** | - | 0.35 ** | −0.08 | 0.19 ** | 0.07 | 0.25 ** | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.23 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.24 ** |

| 10 | Well-being (1) | 3.50 | 0.90 | 0.83 | −0.65 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.07 | −0.51 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.34 ** | - | −0.54 ** | 0.29 ** | −0.27 ** | 0.04 | −0.38 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.66 ** |

| 11 | Past-Negative (2) | 2.80 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.79 ** | −0.32 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.12 | 0.43 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.40 ** | −0.06 | −0.56 ** | - | −0.30 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.08 | 0.46 ** | −0.17 * | −0.29 ** | −0.45 ** | −0.06 | −0.58 ** |

| 12 | Past-Positive (2) | 3.56 | 0.67 | 0.81 | −0.28 ** | 0.81 ** | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.11 | 0.30 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.32 ** | - | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.40 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.27 ** |

| 13 | Present-Fatalistic (2) | 2.48 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.34 ** | −0.01 | 0.71 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.29 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.24 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.07 | - | 0.24 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.39 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.22 ** | 0.01 | −0.37 ** |

| 14 | Present-Hedonistic (2) | 3.19 | 0.51 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.24 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.03 | −0.29 ** | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.29 ** | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.25 ** | - | −0.10 | −0.30 ** | 0.05 | 0.16 * | 0.31 ** | 0.18 ** |

| 15 | Future-Negative (2) | 3.04 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.47 ** | −0.11 | 0.32 ** | 0.03 | 0.69 ** | −0.08 | −0.20 ** | −0.34 ** | 0.02 | −0.38 ** | 0.47 ** | −0.08 | 0.35 ** | −0.04 | - | 0.02 | −0.16 * | −0.40 ** | −0.03 | −0.42 ** |

| 16 | Future-Positive (2) | 3.66 | 0.52 | 0.78 | −0.19 ** | 0.17 * | −0.41 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.00 | 0.79 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.22 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.12 | −0.37 ** | −0.27 ** | 0.02 | - | 0.34 ** | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.26 ** |

| 17 | Gratitude (2) | 5.47 | 0.94 | 0.83 | −0.27 ** | 0.41 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.04 | −0.016 * | 0.27 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.43 ** | −0.30 ** | 0.43 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.08 | −0.15 * | 0.36 ** | - | 0.38 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.50 ** |

| 18 | Savoring (2) | 4.80 | 1.05 | 0.87 | −0.49 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.08 | −0.42 ** | 0.05 | 0.40 ** | 0.79 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.47 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.14 * | −0.41 ** | 0.10 | 0.39 ** | - | 0.29 ** | 0.57 ** |

| 19 | Prioritizing positivity (2) | 7.02 | 1.40 | 0.84 | −0.07 | 0.18 ** | 0.02 | 0.26 ** | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.24 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.03 | 0.21 ** | 0.02 | 0.34 ** | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.32 ** | 0.26 ** | - | 0.33 ** |

| 20 | Well-being (2) | 3.48 | 0.82 | 0.85 | −0.51 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.02 | −0.38 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.068 ** | −0.59 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.34 ** | 0.17 * | −0.43 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.31 ** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burzynska-Tatjewska, B.; Matthews, G.; Stolarski, M. Seeking Causality in the Links between Time Perspectives and Gratitude, Savoring the Moment and Prioritizing Positivity: Initial Empirical Test of Three Conceptual Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084776

Burzynska-Tatjewska B, Matthews G, Stolarski M. Seeking Causality in the Links between Time Perspectives and Gratitude, Savoring the Moment and Prioritizing Positivity: Initial Empirical Test of Three Conceptual Models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084776

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurzynska-Tatjewska, Bozena, Gerald Matthews, and Maciej Stolarski. 2022. "Seeking Causality in the Links between Time Perspectives and Gratitude, Savoring the Moment and Prioritizing Positivity: Initial Empirical Test of Three Conceptual Models" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084776

APA StyleBurzynska-Tatjewska, B., Matthews, G., & Stolarski, M. (2022). Seeking Causality in the Links between Time Perspectives and Gratitude, Savoring the Moment and Prioritizing Positivity: Initial Empirical Test of Three Conceptual Models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084776