Communication about Prognosis and End-of-Life in Heart Failure Care and Experiences Using a Heart Failure Question Prompt List

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting: Communication Course and the HF-QPL

2.3. Sample and Procedure

2.4. Procedure and Data Collection

- Assignment 1: Based on your profession, think about the timepoint that you find suitable for talking about prognosis with a HF patient for the first time. Explain why you feel that the chosen timepoint is suitable.

- Assignment 2: Read through the QPL and think about what questions you have knowledge about and are able to discuss with the patient and their family members. Based on your profession, reflect upon what your role should be in the communication about prognosis and end-of-life. Select three questions from the QPL that you feel would be difficult to discuss with a patient and their family members.

- Assignment 3: Provide the QPL to one patient and/or one family members and let them have some time read it and highlight questions that they want to discuss. Discuss the selected questions. When the conversation has ended, write down what worked and what did not work during the conversation. Reflect upon your role in the conversation, your strengths and what you can improve upon. You are free to choose the timepoint you find the most suitable to give the QPL to the patient/family members.

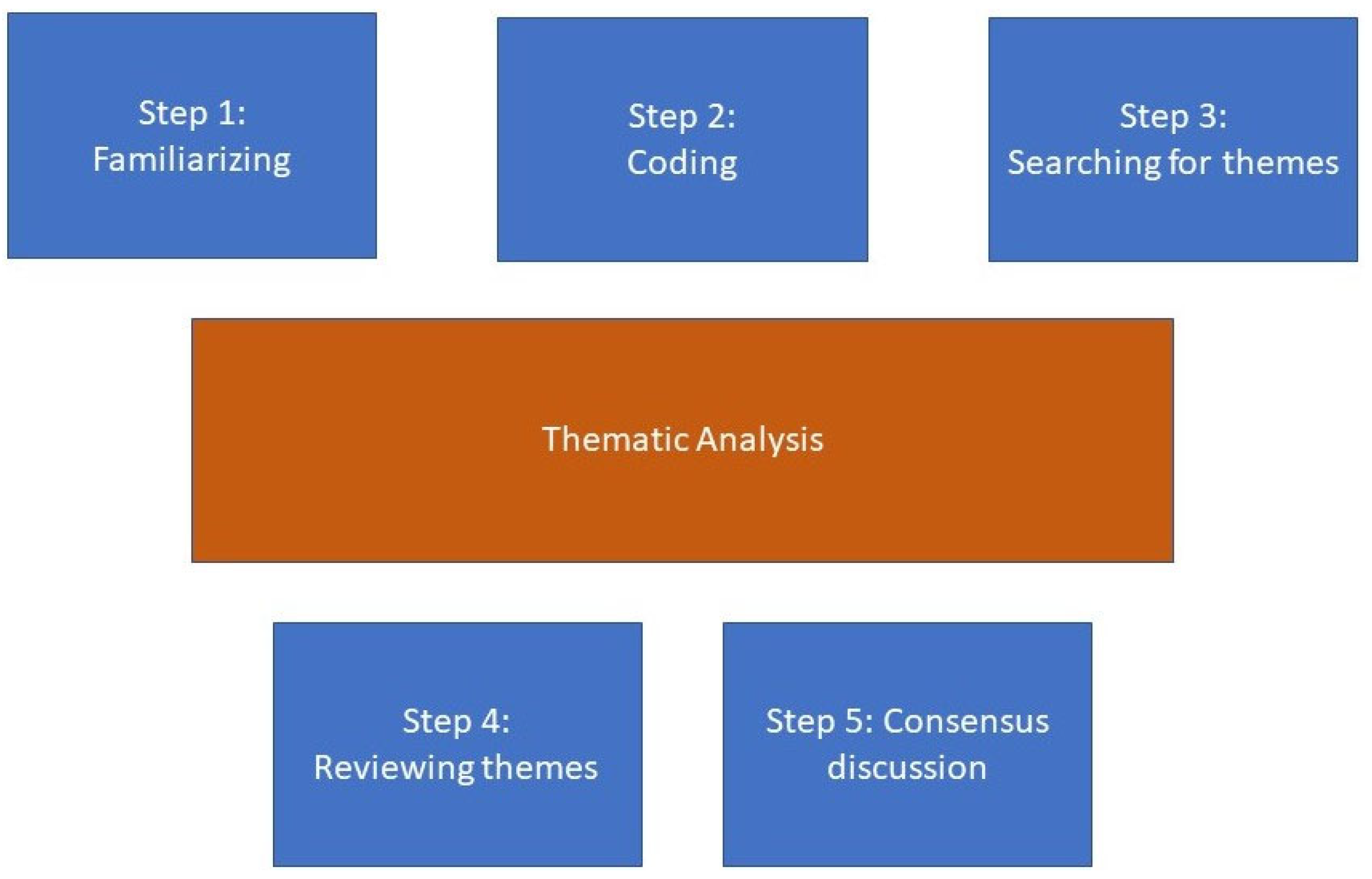

2.5. Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Awareness of Professional Role Responsibilities

Spontaneously, it feels as if the main responsibility for talking about prognosis is expected to lie with the physician. In breakpoint conversations in the ward where I work, we usually include both physicians and nurses, but at least in the first session it is mostly the physician who talks about prognosis. The nurse sits along as an extra ear and sounding board in that situation, both for the patient’s sake and for our own, for feedback and for questions about care.(Physician)

As a nurse, you have an important role in informing and discussing with patients and their loved ones about prognosis and the end of life. I think all patients have the right to have one or more proper conversations with a physician who is familiar with the patient. But after that, we nurses have a great importance for patients and relatives. We see the patient more and usually get a little closer to the patient, get to know them.(Nurse)

3.2. The Importance of Being Optimally Prepared

I felt there was a need to discuss his prognosis and I had prepared well by thinking what I wanted to say and what questions he might ask.(Nurse)

It is so important not to impose any information that a patient is not prepared for. How do you keep that balance? I think that is by far the most difficult. Sometimes I feel inadequate and like I haven’t done my job in case I haven’t done my “duty” and told a patient that he/she is going to die. But just as often I think, when I (after giving a difficult message or having a conversation about progress of a serious chronic illness) have tried in several different ways to find out if the patient has more thoughts and still gets evasive answers, they probably are not fully prepared to hear a straight answer either but need to deal with the situation in a different way. And it’s my duty to feel that need. I’m not sure what’s right or wrong. Is it always right to wait? Is it always wrong to rush it? The patient dies without knowing (or does he/she really?) Is this always bad?(Physician)

3.3. Confidence and Skills Are Required to Use the HF-QPL

I felt it became an honest communication. My experience allowed me to give a straight answer to the questions without feeling stressed. Some questions don’t have an easy answer, but it felt like the patient understood that.(Nurse)

One should be responsive and respect what and how much the individual patient wants to know. Some patients do not want to know anything at all, and you then must meet the patient where they are and talk about what they want to talk about.(Nurse)

3.4. The HF-QPL Is a Bridge in the Communication

It felt good to have the tool included as support. It became like a bridge between us, and we could browse it together and think and talk about it. I felt the conversation was getting less charged because of it. Without the tool, it would have been difficult to come up with questions to ask, I think, and it would probably have been difficult for the patient and relatives to get started talking as well.(Nurse)

3.5. Challenges of the Question Prompt List

Can we really know when a patient is going to die? How does the patient react when the pacemaker is switched off? How long will it take? We are usually unable to answer these questions. We leave the patient without them getting an answer, which makes things worse. I want to be able to give answers, be able to comfort, but how do you do it when you don’t know?(Nurse)

Questions about the last days of life, I think, are more difficult, partly because these are questions that feel difficult/tough and partly because these are topics that I am not used to talking about; these are also questions that may not have any real answers.(Nurse)

The first thought when reading the brochure is Oops, before this is provided, the patient and their relatives must at least have received some information about the diagnosis, otherwise they will probably get a shock!(Physician)

4. Discussion

Methodological Reflections

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fitzsimons, D.; Mullan, D.; Wilson, J.S.; Conway, B.; Corcoran, B.; Dempster, M.; Gamble, J.; Stewart, C.; Rafferty, S.; McMahon, M.; et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat. Med. 2007, 21, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelmfors, L.; Stromberg, A.; Friedrichsen, M.; Sandgren, A.; Martensson, J.; Jaarsma, T. Using co-design to develop an intervention to improve communication about the heart failure trajectory and end-of-life care. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, P.H.; Arthur, H.M.; Demers, C. Preferences of patients with heart failure for prognosis communication. Can. J. Cardiol. 2007, 23, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hill, L.; McIlfatrick, S.; Taylor, B.; Dixon, L.; Harbinson, M.; Fitzsimons, D. Patients’ perception of implantable cardioverter defibrillator deactivation at the end of life. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, L.; Prager Geller, T.; Baruah, R.; Beattie, J.M.; Boyne, J.; de Stoutz, N.; di Stolfo, G.; Lambrinou, E.; Skibelund, A.K.; Uchmanowicz, I.; et al. Integration of a palliative approach into heart failure care: A European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association position paper. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 2327–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, S.; Momen, N.; Case-Upton, S.; Kuhn, I.; Smith, E. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br. Br J Gen Pract. 2011, 61, e49–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelmfors, L.; Stromberg, A.; Friedrichsen, M.; Martensson, J.; Jaarsma, T. Communicating prognosis and end of life care to heart failure patients: A survey of heart failure nurses’ perspectives. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nur. 2014, 13, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salins, N.; Ghoshal, A.; Hughes, S.; Preston, N. How views of oncologists and haematologists impacts palliative care referral: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmfors, L.; van der Wal, M.H.; Friedrichsen, M.J.; Mårtensson, J.; Strömberg, A.; Jaarsma, T. Patient-Nurse Communication about Prognosis and End-of-Life Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansoni, J.E.; Grootemaat, P.; Duncan, C. Question Prompt Lists in health consultations: A review. Patient. Educ Couns. 2015, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S. Application in continuing education for the health professions: Chapter five of “Andragogy in Action”. Mobius 1985, 5, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, V.; Brown, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; APA, Ed.; Vol 2 Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmfors, L.; van der Wal, M.H.L.; Friedrichsen, M.; Milberg, A.; Mårtensson, J.; Sandgren, A.; Strömberg, A.; Jaarsma, T. Optimizing of a question prompt list to improve communication about the heart failure trajectory in patients, families, and health care professionals. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, H.; Rupert, D.J.; Etta, V.; Peinado, S.; Wolff, J.L.; Lewis, M.A.; Chang, P.; Cené, C.W. Examining Information Needs of Heart Failure Patients and Family Companions using a Pre-Visit Question Prompt List and Audiotaped Data: Findings from a Pilot Study. J. Cardiac. Fail. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.R.; Hobbs, F.R.; Taylor, C.J. The management of diagnosed heart failure in older people in primary care. Maturitas 2017, 106, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wal, M.H.L.; Hjelmfors, L.; Strömberg, A.; Jaarsma, T. Cardiologists’ attitudes on communication about prognosis with heart failure patients. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 878–882. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, A.; Cewers, E.; Ben Gal, T.; Weinstein, J.M.; Strömberg, A.; Jaarsma, T. Perspectives of health care providers on the role of culture in the self-care of patients with chronic heart failure: A qualitative interview study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, K.P.; Rutten, F.H.; Klompstra, L.; Bhana, Y.; Sieverink, F.; Ruschitzka, F.; Seferovic, P.M.; Lainscak, M.; Piepoli, M.F.; Broekhuizen, B.D.L.; et al. ‘heartfailurematters.org’, an educational website for patients and carers from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology: Objectives, use and future directions. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Blue, L.; Clark, A.L.; Dahlström, U.; Ekman, I.; Lainscak, M.; McDonald, K.; Ryder, M.; Strömberg, A.; Jaarsma, T.; et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association Standards for delivering heart failure care. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.G.; Zambroski, C.H. Upstreaming palliative care for patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nur. 2012, 27, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, T.; Beattie, J.M.; Ryder, M.; Rutten, F.H.; McDonagh, T.; Mohacsi, P.; Murray, S.A.; Grodzicki, T.; Bergh, I.; Metra, M.; et al. Palliative care in heart failure: A position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009, 11, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDarby, M.; Mroz, E.; Carpenter, B.D.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Kamal, A. A Research Agenda for the Question Prompt List in Outpatient Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 1596–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walczak, A.; Henselman, I.; Tattersall, M.H.N.; Clayton, J.M.; Davidson, P.M.; Butow, P.N. A qualitative analysis of responses to a question prompt list and prognosis and end-of-life care discussion prompts delivered in a communication support program. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouleuc, C.; Savignoni, A.; Chevrier, M.; Renault-Tessier, E.; Burnod, A.; Chvetzoff, G.; Poulain, P.; Copel, L.; Cottu, P.; Pierga, J.-Y.; et al. A Question Prompt List for Advanced Cancer Patients Promoting Advance Care Planning: A French Randomized Trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Female sex, n (%) | 15 (100%) |

| Age, mean ± sd | 40 ± 12 |

| Occupation, n (%) | |

| Nurse | 13 (87%) |

| Physician | 2 (13%) |

| Workplace | |

| Hospital | 13 (87%) |

| Primary care center | 2 (13%) |

| Years working in health care, mean ± sd | 16 ± 13 |

| Years working with patients with HF, mean ± sd | 9 ± 8 |

| Work percentage working with patients with HF per week (range) | 5–100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hjelmfors, L.; Mårtensson, J.; Strömberg, A.; Sandgren, A.; Friedrichsen, M.; Jaarsma, T. Communication about Prognosis and End-of-Life in Heart Failure Care and Experiences Using a Heart Failure Question Prompt List. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084841

Hjelmfors L, Mårtensson J, Strömberg A, Sandgren A, Friedrichsen M, Jaarsma T. Communication about Prognosis and End-of-Life in Heart Failure Care and Experiences Using a Heart Failure Question Prompt List. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084841

Chicago/Turabian StyleHjelmfors, Lisa, Jan Mårtensson, Anna Strömberg, Anna Sandgren, Maria Friedrichsen, and Tiny Jaarsma. 2022. "Communication about Prognosis and End-of-Life in Heart Failure Care and Experiences Using a Heart Failure Question Prompt List" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084841

APA StyleHjelmfors, L., Mårtensson, J., Strömberg, A., Sandgren, A., Friedrichsen, M., & Jaarsma, T. (2022). Communication about Prognosis and End-of-Life in Heart Failure Care and Experiences Using a Heart Failure Question Prompt List. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084841