A Solution for Loneliness in Rural Populations: The Effects of Osekkai Conferences during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Setting

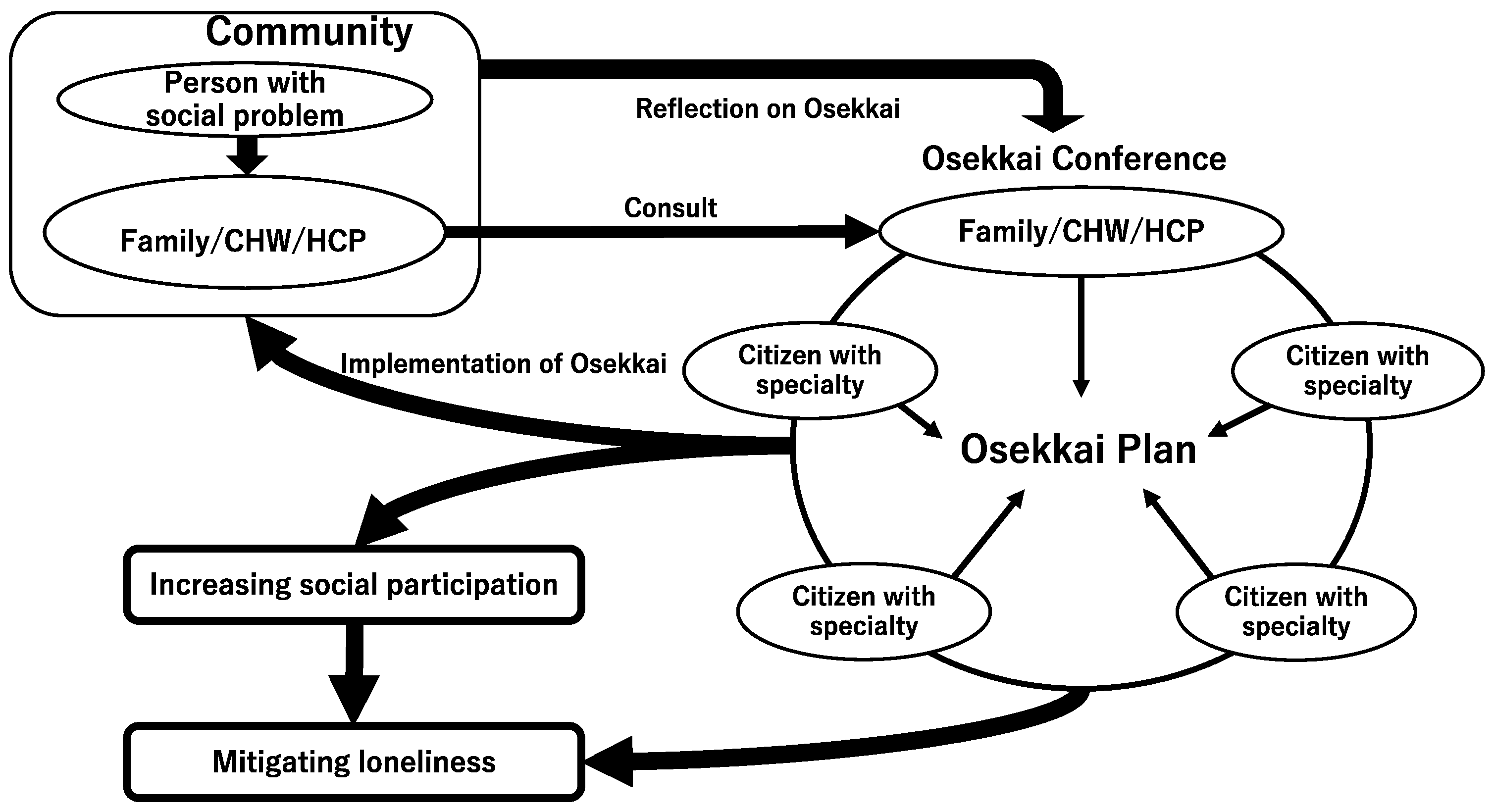

2.2. Osekkai Conference

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measurements

2.5. Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of the Participants

3.2. Changes in the Role of Osekkai Conferences during the Study Period

3.3. Changes in the Degree of Loneliness and the Frequency and Numbers of Meeting with Friends or Acquaintances

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mehrabi, F.; Béland, F. Frailty as a Moderator of the Relationship between Social Isolation and Health Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Hawkley, L.C.; Waite, L.J.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness, Health, and Mortality in Old Age: A National Longitudinal Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luanaigh, C.O.; Lawlor, B.A. Loneliness and the Health of Older People. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Kataoka, D.; Sano, C. Effectiveness and Challenges in Local Self-Governance: Multifunctional Autonomy in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. Social Capital and Life Satisfaction across Older Rural Chinese Groups: Does Age Matter? Soc. Work 2018, 63, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Sano, C.; Könings, K.D. Educational Intervention to Improve Citizen’s Healthcare Participation Perception in Rural Japanese Communities: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenade, L.; Boldy, D. Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older People: Issues and Future Challenges in Community and Residential Settings. Aust. Health Rev. 2008, 32, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Choe, K.; Kang, Y. Anxiety of Older Persons Living Alone in the Community. Healthcare 2020, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, R.V.; Newall, N.E.G.; Lawrence, B.C.; Ramsey, D.; Waddell, C.M.; Dauphinais, J. Conversations in Times of Isolation: Exploring Rural-Dwelling Older Adults’ Experiences of Isolation and Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Manitoba, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Coco, G.; Gentile, A.; Bosnar, K.; Milovanović, I.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P.; Pišot, S. A Cross-Country Examination on the Fear of COVID-19 and the Sense of Loneliness during the First Wave of COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Rai, M. Social Isolation in COVID-19: The Impact of Loneliness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickerdike, L.; Booth, A.; Wilson, P.M.; Farley, K.; Wright, K. Social Prescribing: Less Rhetoric and More Reality. A Systematic Review of the Evidence. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drinkwater, C.; Wildman, J.; Moffatt, S. Social Prescribing. BMJ 2019, 364, l1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husk, K.; Blockley, K.; Lovell, R.; Bethel, A.; Lang, I.; Byng, R.; Garside, R. What Approaches to Social Prescribing Work, for Whom, and in What Circumstances? A Realist Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pescheny, J.V.; Randhawa, G.; Pappas, Y. The Impact of Social Prescribing Services on Service Users: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Yata, A. The Revitalization of “Osekkai”: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Emphasized the Importance of Japanese Voluntary Social Work. Qual. Soc. Work 2021, 20, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Yata, A.; Arakawa, Y.; Maiguma, K.; Sano, C. Rural Social Participation through Osekkai during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Ohta, R.; Sano, C. Solving Social Problems in Aging Rural Japanese Communities: The Development and Sustainability of the Osekkai Conference as a Social Prescribing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Sano, C. Fears Related to COVID-19 among Rural Older People in Japan. Healthcare 2021, 9, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence-Bourne, J.; Dalton, H.; Perkins, D.; Farmer, J.; Luscombe, G.; Oelke, N.; Bagheri, N. What Is Rural Adversity, How Does It Affect Wellbeing and What Are the Implications for Action? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. The Growing Problem of Loneliness. Lancet 2018, 391, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harden, S.M.; Smith, M.L.; Ory, M.G.; Smith-Ray, R.L.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Glasgow, R.E. RE-AIM in Clinical, Community, and Corporate Settings: Perspectives, Strategies, and Recommendations to Enhance Public Health Impact. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Cable, N.; Aida, J.; Shirai, K.; Saito, M.; Kondo, K. Validation Study on a Japanese Version of the Three-Item UCLA Loneliness Scale among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 1068–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, K.; Tsuji, T.; Kanamori, S.; Jeong, S.; Nagamine, Y.; Kondo, K. Social Participation and Functional Decline: A Comparative Study of Rural and Urban Older People, Using Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study Longitudinal Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Lukwago, S.N.; Bucholtz, R.D.; Clark, E.M.; Sanders-Thompson, V. Achieving Cultural Appropriateness in Health Promotion Programs: Targeted and Tailored Approaches. Health Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, D.; Cui, R.; Haregot Hilawe, E.; Chiang, C.; Hirakawa, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, P.; Iso, H.; Aoyama, A. Facilitators and Barriers of Adopting Healthy Lifestyle in Rural China: A Qualitative Analysis through Social Capital Perspectives. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2016, 78, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson, S.; Terceira, N.; Mushati, P.; Nyamukapa, C.; Campbell, C. Community Group Participation: Can It Help Young Women to Avoid H.I.V.? an Exploratory Study of Social Capital and School Education in Rural Zimbabwe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 2119–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pronyk, P.M.; Harpham, T.; Busza, J.; Phetla, G.; Morison, L.A.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Watts, C.H.; Porter, J.D. Can Social Capital Be Intentionally Generated? A Randomized Trial from Rural South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamada, M.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Abe, T.; Taguri, M.; Inoue, S.; Ishikawa, Y.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I.M.; Miyachi, M.; Kawachi, I. Community-Wide Intervention and Population-Level Physical Activity: A 5-Year Cluster Randomized Trial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessaha, M.L.; Sabbath, E.L.; Morris, Z.; Malik, S.; Scheinfeld, L.; Saragossi, J. A Systematic Review of Loneliness Interventions among Non-Elderly Adults. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2020, 48, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D.V.; Lee, E.E.; Cacioppo, S. Battling the Modern Behavioral Epidemic of Loneliness: Suggestions for Research and Interventions. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 553–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcham, R.; Silas, E.; Irie, J. Health Promotion and Empowerment in Henganofi District, Papua New Guinea. Rural Remote Health 2016, 16, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocloo, J.; Matthews, R. From Tokenism to Empowerment: Progressing Patient and Public Involvement in Healthcare Improvement. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brodsky, A.E.; Cattaneo, L.B. A Transconceptual Model of Empowerment and Resilience: Divergence, Convergence and Interactions in Kindred Community Concepts. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 52, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Soucie, K.; Matsuba, K.; Pratt, M.W. Meaning in Life Mediates the Association between Environmental Engagement and Loneliness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.J.; Lim, M.H. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Focusing Attention on Loneliness and Social Isolation. Public Health Res. Pract. 2020, 30, 3022008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitas, N.; Ehmer, C. Social Capital in the Response to COVID-19. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, C.; Sanchez-Pages, S. Social Capital, Conflict and Welfare. J. Dev. Econ. 2017, 124, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.; Wen, S. Does Social Capital Contribute to Prevention and Control of the COVID-19 Pandemic? Empirical Evidence from China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 64, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlani-Duault, L.; Chauvin, F.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Lina, B.; Benamouzig, D.; Bouadma, L.; Druais, P.L.; Hoang, A.; Grard, M.A.; Malvy, D.; et al. France’s COVID-19 Response: Balancing Conflicting Public Health Traditions. Lancet 2020, 396, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, M.D. Shared Leadership in Health Care Organizations. Top. Health Care Financ. 1994, 20, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brune, N.E.; Bossert, T. Building Social Capital in Post-Conflict Communities: Evidence from Nicaragua. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skivington, K.; Smith, M.; Chng, N.R.; Mackenzie, M.; Wyke, S.; Mercer, S.W. Delivering a Primary Care-Based Social Prescribing Initiative: A Qualitative Study of the Benefits and Challenges. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, e487–e494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, F.; Andrieu, E. Bowling Together by Bowling Alone: Social Capital and COVID-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Ueno, A.; Sano, C. Changes in the Comprehensiveness of Rural Medical Care for Older Japanese Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Record, J.D.; Ziegelstein, R.C.; Christmas, C.; Rand, C.S.; Hanyok, L.A. Delivering personalized care at a distance: How telemedicine can foster getting to know the patient as a person. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Khera, S.; Dabravolskaj, J.; Chevalier, B.; Parker, K. The seniors’ community hub: An integrated model of care for the identification and management of frailty in primary care. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Brittain, K.; Tansey, R.; Williams, K. How People Decide to Seek Health Care: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1516–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N = 77 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.5 (16.8) |

| Male sex (%) | 23 (29.9) |

| High education level (%) | 56 (72.7) |

| High socioeconomic status (%) | 51 (66.2) |

| Consumes alcohol (%) | 35 (45.5) |

| Smoker (%) | 3 (3.9) |

| Regular health check (%) | 49 (63.6) |

| Having chronic diseases (%) | 28 (36.4) |

| Living with family (%) | 65 (84.4) |

| Living location, Unnan (%) | 63 (81.8) |

| High social support (%) | 65 (84.4) |

| Role in the Conference | 2020 | 2021 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consulting difficulties in communities | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.278 |

| Organizing the conference | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.167 |

| Planning Osekkai | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.798 |

| Performing Osekkai | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.349 |

| Supporting Osekkai | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.552 |

| Accepting Osekkai | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.397 |

| Period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | 2021 | 2022 | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

| Loneliness, mean (SD) | 4.25 (1.34) | 4.05 (1.21) | 0.099 | 0.16 |

| Item 1, mean (SD) | 1.58 (0.55) | 1.54 (0.58) | 0.605 | 0.04 |

| Item 2, mean (SD) | 1.36 (0.56) | 1.25 (0.46) | 0.038 | 0.22 |

| Item 3, mean (SD) | 1.31 (0.49) | 1.29 (0.51) | 0.596 | 0.04 |

| Meeting frequency | 0.39 | 0.40 | >0.99 | |

| Number of meetings | 0.55 | 0.53 | >0.99 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohta, R.; Maiguma, K.; Yata, A.; Sano, C. A Solution for Loneliness in Rural Populations: The Effects of Osekkai Conferences during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095054

Ohta R, Maiguma K, Yata A, Sano C. A Solution for Loneliness in Rural Populations: The Effects of Osekkai Conferences during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095054

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhta, Ryuichi, Koichi Maiguma, Akiko Yata, and Chiaki Sano. 2022. "A Solution for Loneliness in Rural Populations: The Effects of Osekkai Conferences during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095054