The Association between Parental Marital Satisfaction and Adolescent Prosocial Behavior in China: A Moderated Serial Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Marital Satisfaction and Adolescents’ Prosocial Behavior

1.2. Parent–Child Relationship as a Potential Mediator

1.3. Empathy as Another Potential Mediator

1.4. The Relationship between the Parent–Child Relationship and Empathy

1.5. The Potential Moderating Effect of Gender

1.6. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Marital Satisfaction

2.2.2. Adolescents’ Prosocial Behavior

2.2.3. Adolescents’ Empathy

2.2.4. The Parent–Child Relationship

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

| Variables | Girls (M ± SD) | Boys (M ± SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Marital satisfaction | 3.98 ± 0.69 | 3.98 ± 0.68 | - | 0.31 ** | 0.15 * | 0.15 |

| 2. Parent–child relationship | 3.09 ± 0.53 | 3.05 ± 0.55 | 0.31 * | - | 0.31 ** | 0.18 ** |

| 3. Empathy | 3.85 ± 0.62 | 4.08 ± 0.53 | 0.08 | 0.07 | - | 0.66 ** |

| 4. Prosocial behavior | 5.33 ± 1.02 | 5.61 ± 0.83 | 0.11 | 0.17 * | 0.37 * | - |

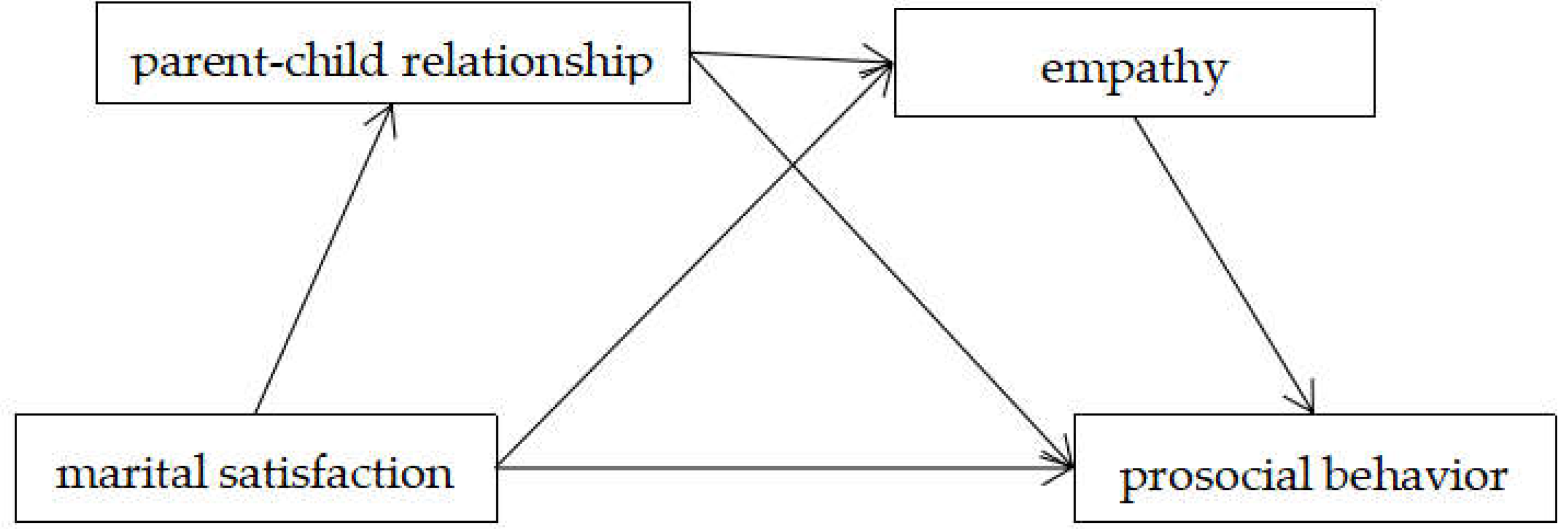

3.2. Mediating Model Analyses

3.3. Multiple-Group Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development; Eisenberg, N., Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, M.; Rubin, K.H.; Cen, G.Z.; Gao, X.; Li, D. Sociability and prosocial orientation as predictors of youth adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study in a Chinese sample. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2002, 26, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Knafo-Noam, A. Prosocial development. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, 7th ed.; Lerner, R.M., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 610–656. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Qu, Y.; Li, X.R. Parental Collectivism Goals and Chinese Adolescents’ Prosocial Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Authoritative Parenting. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streit, C.; Carlo, G.; Knight, G.P.; White, R.M.B.; Maiya, S. Relations Among Parenting, Culture, and Prosocial Behaviors in US Mexican Youth: An Integrative Socialization Approach. Child Dev. 2021, 92, E383–E397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Bai, L.; Chen, Y. The relationship between marital quality and adolescents′ prosocial and problem behaviors: The mediating roles of parents′ parenting competence. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2017, 15, 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, K.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive marital conflict, emotional security, and children’s prosocial behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindsey, E.W.; Colwell, M.J.; Frabutt, J.M.; MacKinnon-Lewis, C. Family conflict in divorced and non-divorced families: Potential consequences for boys’ friendship status and friendship quality. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 23, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, D.; Doyle, A.B.; Brendgen, M. The quality of adolescents' friendships: Associations with mothers' interpersonal relationships, attachments to parents and friends, and prosocial behaviors. J. Adolesc. 2001, 24, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, M.; Lecce, S.; Pagnin, A.; Banerjee, R. Longitudinal effects of theory of mind on later peer relations: The role of prosocial behavior. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, F.; Siu, A.; Shek, D. Individual and social predictors of prosocial behavior among chinese adolescents in hong kong. Front. Pediatrics 2015, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoo, H.; Feng, X.; Day, R.D. Adolescents’ Empathy and Prosocial Behavior in the Family Context: A Longitudinal Study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1858–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, A.; Ghazarian, S.R.; Day, R.D.; Riley, A.W. Maternal emotion regulation and adolescent behaviors: The mediating role of family functioning and parenting. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 2321–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henneberger, A.K.; Varga, S.M.; Moudy, A.; Tolan, P.H. Family functioning and high risk adolescents′ aggressive behavior: Examining effects by ethnicity. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hart, D.; Carlo, G. Moral development in adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2005, 15, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J.M. What Predicts Divorce? The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meschke, L.L.; Juang, L.P. Obstacles to parent–adolescent communication in Hmong American families: Exploring pathways to adolescent mental health promotion. Ethn. Health 2014, 19, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepke, S.; Denissen, J.J.A. Dynamics of identity development and separation-individuation in parent-child relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood-A conceptual integration. Dev. Rev. 2012, 32, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouros, C.D.; Papp, L.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M. Spillover between marital quality and parent-child relationship quality: Parental depressive symptoms as moderators. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, Z.B.; Zhang, G.Z.; Deng, H.H.; Song, Y.; Zheng, W.M.; Sun, L. Links between marital relationship and child-parent relationship: Mediating effects of parents’ emotional expressiveness. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2013, 45, 1355–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, R. Renegotiating Family Relationships: Divorce, Child Custody, and Mediation; Guilford Press: New York, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Yuan, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Parental conflict and Infants’ problem behavior: A moderated mediating model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 736–741. [Google Scholar]

- Sallquist, J.; Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eggum, N.D.; Gaertner, B.M. Assessment of preschoolers' positive empathy: Concurrent and longitudinal relations with positive emotion, social competence, and sympathy. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batson, C.D.; Shaw, L.L. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychol. Inq. 1991, 2, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wei, B.; Xiong, H. Parenting style and adolescents’ pro-social behaviors: The mediating role of empathy. Psychol. Explor. 2020, 4, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.C.; Wu, X.C. Mediating roles of gratitude, social support and post-traumatic growth in the relation between empathy and prosocial behavior among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2020, 52, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.Y.; Bradley-Klug, K.; Chenneville, T. Health-related quality of life and mental health indicators in adolescents with HIV compared to a community sample in the Southeastern US. AIDS care-psychological and socio-medical aspects of AIDS/HIV. AIDS Care 2017, 29, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, N.; Banerjee, R. Maltreated children’s social understanding and empathy: A preliminary exploration of foster carers’ perspectives. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.Y.; Li, B.B.; Wu, Y.X.; Xu, R.; Jin, P.P. The effect of family environment for helping behavior in middle school students: Mediation of self-efficacy and empathy. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. 2018, 269, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Knafo, A.; Zahn-Waxler, C.; Van Hulle, C.; Robinson, J.L.; Rhee, S.H. The developmental origins of a disposition toward empathy: Genetic and environmental contributions. Emotion 2008, 8, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Christensen, K.J. Empathy and self-regulation as mediators between parenting and adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boele, S.; Jolien, V.D.G.; De Wied, M.; Van, d.V.I.E.; Crocetti, E.; Branje, S. Linking parent-child and peer relationship quality to empathy in adolescence: A multilevel meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christov-Moore, L.; Simpson, E.A.; Coudé, G.; Grigaityte, K.; Iacoboni, M.; Ferrari, P.F. Empathy: Gender effects in brain and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 46, 604–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, H. Gender difference in empathy and possible reasons. J. Southwest Univ. 2014, 40, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, E.; Spataro, P.; Rossi-Arnaud, C. Direct and indirect associations of empathy, theory of mind, and language with prosocial behavior: Gender differences in primary school children. J. Genet. Psychol. 2019, 180, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Graaff, J.; Carlo, G.; Crocetti, E.; Koot, H.M.; Branje, S. Prosocial behavior in adolescence: Gender differences in development and links with empathy. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1086–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McMahon, S.D.; Wernsman, J.; Parnes, A.L. Understanding prosocial behavior: The impact of empathy and gender among African American adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roubinov, D.S.; Boyce, W.T. Parenting and SES: Relative values or enduring principles? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 15, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueckert, L.; Naybar, N. Gender Differences in Empathy: The Role of the Right Hemisphere. Brain Cognit. 2008, 67, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Tang, Z.; Li, T. Parent-child Relationship and Cyberbullying in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 28, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Kou, Y. The Dimension of Measurement on Prosocial Behavior: Exploration and confirmation. J. Sociol. Study 2011, 26, 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, S.S.; Dicke, A.; Hendrick, C. The relationship assessment scale. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1998, 15, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, B.; Wu, W. Reliability and validity of early father-child relationship scale in China. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 16, 13–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.J.; Fang, X.Y.; Deng, L.Y.; Lin, X.Y. The Relationship among in-law Relations, Partner Support under Conflicts with in-laws and Marital Quality. Stud. Psychol. Behavior. 2015, 13, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.J.; Fang, X.Y. Origin Family Support and Its Relation to Marital Quality in Chinese Couples. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 24, 495–498. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.J.; Fang, X.Y. Interference from Family of Origin and Divorce Tendency: The Mediating Effect of Marital Quality and the Moderating Effect of Spouse Support. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 30, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo, G.; Randall, B.A. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, A.M.H.; Shek, D.T.L. Validation of the interpersonal reactivity index in a Chinese context. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2005, 15, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C. Child-Parent Relationship Scale; University of Virginia: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jaureguizar, J.; Ibabe, I.; Straus, M.A. Violent and prosocial behavior by adolescents toward parents and teachers in a community sample. Psychol. Sch. 2013, 50, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.Z.; Zhang, L.L.; Wei, X.; Zhang, W.X.; Chen, L.; Ji, L.X.; Chen, X.Y. The Stability of Internalizing Problem and Its Relation to Maternal Parenting during Early Adolescence. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2015, 16, 527–537. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.X.; Fuligni, A.J. Authority, autonomy, and family relationships among adolescents in urban and rural china. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.P.; Lynch, M.E. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In Girls at Puberty; Brooks-Gunn, J., Petersen, A.C., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, P.D.; Miller, J.G.; Troxel, N.R. Making good: The socialization of children’s prosocial development. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research; Grusec, J.E., Hastings, P.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 637–660. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Guo, Y.; Bai, B.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Cheng, L. The Association between Parental Marital Satisfaction and Adolescent Prosocial Behavior in China: A Moderated Serial Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095630

Zhang R, Guo Y, Bai B, Wang Y, Gao L, Cheng L. The Association between Parental Marital Satisfaction and Adolescent Prosocial Behavior in China: A Moderated Serial Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095630

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ruiping, Yaqian Guo, Baoyu Bai, Yabing Wang, Linlin Gao, and Lan Cheng. 2022. "The Association between Parental Marital Satisfaction and Adolescent Prosocial Behavior in China: A Moderated Serial Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095630

APA StyleZhang, R., Guo, Y., Bai, B., Wang, Y., Gao, L., & Cheng, L. (2022). The Association between Parental Marital Satisfaction and Adolescent Prosocial Behavior in China: A Moderated Serial Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095630