Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Era on Residential Property Features: Pilot Studies in Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

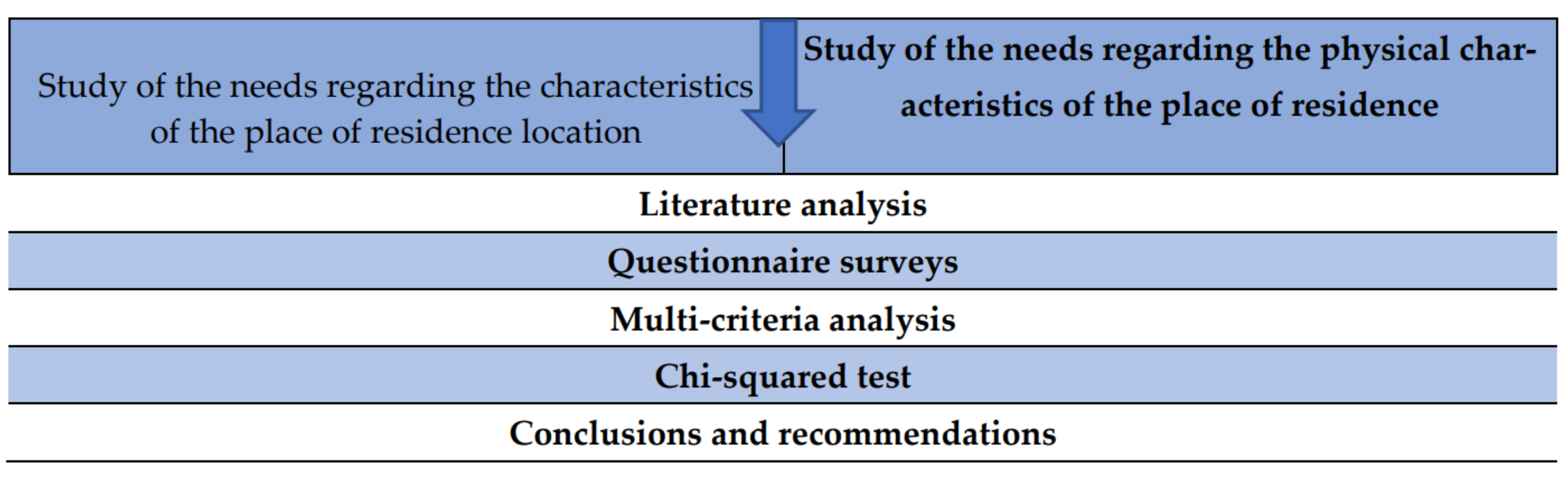

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Research Prospects

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Dąbek, A. W 2021 r. Zmarło w Polsce Ponad pół Miliona Osób. Najtragiczniejszy Rok od Czasów II Wojny Światowej. Available online: https://www.medonet.pl/koronawirus/koronawirus-w-polsce,2021-to-najtragiczniejszy-rok-od-zakonczenia-ii-wojny-swiatowej-,artykul,06476866.html (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Health at a Glance 2021. OECD Indicators. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/ae3016b9-en.pdf?expires=1644919005&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=04BBBFB5FF0219CBFA6DE8F712EB0DF2 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Epidemia Coronawirusa. Available online: https://epidemia-koronawirus.pl/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Bettaieb, D.M.; Alsabban, R. Emerging Living Styles Post-COVID-19: Housing Flexibility as a Fundamental Requirement for Apartments in Jeddah. Archnet-IJAR 2021, 15, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Oteiza, I. A Mixed Approach on Resilience of Spanish Dwellings and Households during COVID-19 Lockdown. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwiazdzinski, L. L’inversion des Saturations ou la Possibilité d’une Autre Ville. Libération. 2020. Available online: https://www.liberation.fr/debats/2020/11/29/l-inversion-des-saturations-ou-la-possibilite-d-une-autre-ville_1806700/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Kaufmann, V. Lockdown. In Proceedings of the Mobile Lives Forum, 11–13 June 2021; Available online: https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/marks/lockdown-13664%0AAll (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Nanda, A.; Thanos, S.; Valtonen, E.; Xu, Y.; Zandieh, R. Forced homeward: The COVID-19 implications for housing. Town Plan. Rev. 2021, 92, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, S.; Baniasad, M.; Niyogi, D. Global to USA County Scale Analysis of Weather, Urban Density, Mobility, Homestay, and Mask Use on COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, D.V. About a Fifth of U.S. Adults Moved Due to COVID-19 or Know Someone Who Did. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/06/about-a-fifth-of-u-s-adults-moved-due-to-covid-19-or-know-someone-who-did/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- McLeod, S. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. 2014. Available online: http://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Maslow, A.H. Higher and Lower needs. J. Psychol. 1948, 25, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMHNP. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maslow%27s_Hierarchy_of_Needs2.svg (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Zdrowie 21. Zdrowie Dla Wszystkich W XXI Wieku. Podstawowe Założenia Polityki Zdrowia dla Wszystkich w Regionie Europejskim WHO; Światowa Organizacja Zdrowia. Biuro Regionu Europejskiego: Copenhagen, Denmark. Available online: https://www.parpa.pl/index.php/alkohol-w-europie/zdrowie-21-zdrowie-dla-wszystkich-who (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Hartig, T.; Kylin, C.; Johansson, G. The Telework Tradeoff: Stress Mitigation vs. Constrained Restoration. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 56, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Lawrence, R.J. Introduction: The Residential Context of Health. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Brambilla, A.; Morganti, A.; Aguglia, A.; Bianchi, D.; Santi, F.; Costantini, L.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Signorelli, C.; et al. COVID-19 Lockdown: Housing Built Environment’s Effects on Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, A. Homes, health, and COVID-19: How poor housing adds to the hardship of the coronavirus crisis. Soc. Mark. Found. 2020. Available online: https://www.smf.co.uk/commentary_podcasts/homes-health-and-covid-19-how-poor-housing-adds-to-the-hardship-of-the-coronavirus-crisis/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Tinson, A.; Clair, A. Better housing is crucial for our health and the COVID-19 recovery. Health Found. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/better-housing-is-crucial-for-our-health-and-the-covid-19-recovery (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Hansmann, R.; Fritz, L.; Pagani, A.; Clément, G.; Binder, C.R. Activities, housing situation, gender and further factors influencing psychological strain experienced during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Switzerland. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, E. What Location, Location, Location Means in Real Estate Why Location Needs to be Repeated Three Times, Updated 28 January 2017. Available online: https://www.tampabgcc.com/files/What%20Location.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Anundsen, A.K.; Bjørland, C.; Hagen, M. Location, location, location!: A quality-adjusted rent index for the Oslo office market. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2021, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, P.M.; Van Eggermond, M.; Axhausen, K.W. The role of location in residential location choice models: A review of literature. J. Transp. Land Use 2014, 7, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, E.; Halman, J.I.; Ion, R.A. Variation in housing design: Identifying customer preferences. Hous. Stud. 2006, 21, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsariniaty, A.W. Analisis Perbandingan Preferensi Masyarakat Golongan Menengah Dalam Memilih Hunian pada Gated Communities di Kawasan Kota dan Pinggiran Kota Bandung: Studi KasusKec. Kiara Condong dan Kec. Parongpong (Comparative Analysis of Middle-Class’ Preferences Choosing to Live in Gated Communities in the Urban and Suburban area of Bandung: Case Study Kec. Kiara Condong and Kec. Parongpong). Master’s Thesis, School of Architecture, Planning, and Policy Development, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kain, J.F.; Quigley, J.M. Measuring the Value of Housing Quality. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1970, 65, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S. Hedonic Prices and Implicit Markets: Product Differentiation in Pure Competition. J. Political Econ. 1974, 82, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jui, J.J.; Imran Molla, M.M.; Bari, B.S.; Rashid, M.; Hasan, M.J. Flat Price Prediction Using Linear and Random Forest Regression Based on Machine Learning Techniques. In Embracing Industry 4.0: Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Mohd Razman, M., Mat Jizat, J., Mat Yahya, N., Myung, H., Zainal Abidin, A., Abdul Karim, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradana, D.P.; Rahadi, R.A. Analysis of Housing Affordability by Generation Y Based on Price to Income Ratio in Jakarta Region. Am. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 3, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rahadi, R.; Wiryono, S.K.; Koesrindartoto, D.P.; Syamwil, I.B. Relationship between Consumer Preferences and Value Propositions: A Study of Residential Product. AcE-Bs 2012 Bangk. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 50, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, W.J. E-Topia-Urban Life, Jim—But Not as We Know It; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.; Won, J.; Kim, E.J. COVID-19 Impact on Residential Preferences in the Early-Stage Outbreak in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.; Hansmann, R.; Kaufmann, V.; Binder, C.R. How the first wave of COVID-19 in Switzerland affected residential preferences. Cities Health 2021, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.F. Teleworker’s home office: An extension of corporate office? Facilities 2010, 28, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Jiménez, C.; Jaime-Segura, C. Living Space Needs of Small Housing in the Post-Pandemic Era: Malaga as a case study. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2022, 6, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Helms, M.M.; Ross, T.J. Technological developments: Shaping the telecommuting work environment of the future. Facilities 2000, 18, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrit, M.; Campbell, D. Student Housing in the COVID-19 Era. Build. Des. Constr. 2020. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/student-housing-covid-19-era/docview/2435774863/se-2?accountid=14568 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Peters, T.; Halleran, A. How our homes impact our health: Using a COVID-19 informed approach to examine urban apartment housing. Archnet-IJAR 2021, 15, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereitschaft, B.; Scheller, D. How Might the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect 21st Century Urban Design, Planning, and Development? Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfour, O.S. Housing Experience in Gated Communities in the Time of Pandemics: Lessons Learned from COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, A. How the COVID-19 Pandemic will Change the Built Environment. Archit. Dig. 2020. Available online: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/covid-19-design (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Haaland, C.; van Den Bosch, C.K. Challenges and Strategies for Urban Green-space Planning in Cities Undergoing Densification: A Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noszczyk, T.; Gorzelany, J.; Kukulska-Kozieł, A.; Hernik, J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the importance of urban green spaces to the public. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marona, B.; Tomal, M. The COVID-19 pandemic impact upon housing brokers’ workflow and their clients’ attitude: Realestate market in Krakow. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 8, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toro, P.; Nocca, F.; Buglione, F. Real Estate Market Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis: Which Prospects for the Metropolitan Area of Naples (Italy)? Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JLL Research & Strategy. COVID-19: Global Real Estate Implications, Paper II; Global Research: Hillsborough, UK, 20 April 2020; Available online: https://www.jll.it/it/tendenze-e-ricerca/research/covid-19-global-real-estate-implications (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Del Giudice, V.; De Paola, P.; Del Giudice, F.P. COVID-19 infects real estate markets: Short and mid-run effects on housing prices in Campania region (Italy). Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, H.I. Deterministic Mathematical Models in Population Biology; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fred, B.; Castillo-Chavez, C. Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4757-3516-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tajani, F.; Liddo, F.D.; Guarini, M.R.; Ranieri, R.; Anelli, D. An Assessment Methodology for the Evaluation of the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Italian Housing Market Demand. Buildings 2021, 11, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustan, L.P.; Kahn, M.E.; Rhode, P.W.; Yanguas, M.L. The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in US counties: A century of data. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 118, 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, M.; Saito, M.; Yamaga, H. Earthquake risks and land prices: Evidence from the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 2009, 60, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakagawa, M.; Saito, M.; Yamaga, H. Earthquake Risks and Housing Rents: Evidence from the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2007, 37, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Giudice, V. Estimo e Valutazione Economica dei Progetti, Profili Metodologici e Applicazioni al Settore Immobiliare; Paolo Loffredo Iniziative Editoriali: Naples, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Belasen, A.R.; Polachek, S.W. How disasters affect local labor markets: The effects of hurricanes in Florida. J. Hum. Resour. 2020, 44, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K. The economic effects of climate change adaptation measures: Evidence from Miami-Dade County and New York City. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tokazhanov, G.; Tleuken, A.; Guney, M.; Turkyilmaz, A.; Karaca, F. How is COVID-19 Experience Transforming Sustainability Requirements of Residential Buildings? A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.; Binder, C.R. A systems perspective for residential preferences and dwellings: Housing functions and their role in Swiss residential mobility. Hous. Stud. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T. Superarchitecture: Building for better health. Archit. Des. 2017, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahadi, R.A.; Saldy, D.R.; Alfita, F.; Handayani, P. Millennials residential preferences in indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic. South-East Asia J. Contemp. Bus. Econ. Law 2021, 24, 2. Available online: https://seajbel.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/SEAJBEL24_548.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Marusiak, M.; Palicki, S.; Strączkowski, Ł.; Roszka, W.; Szymkowiak, M. Diagnoza Potrzeb Mieszkaniowych. Interpretacja Badań Ankietowych pt. Potrzeby i Preferencje Mieszkaniowe Poznaniaków. Spółka Celowa Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu Sp. z o.o. 2015. Available online: https://bip.poznan.pl (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- WHO Healthy. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/behealthy/healthy-diet (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Act of LM, Act of Land Management 21 August 1997. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu19971150741 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Red Book Global Standards. Available online: www.https://www.rics.org/en-za/upholding-professional-standards/sector-standards/valuation/red-book/red-book-global/ (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Stupicki, R. Analiza i Prezentacja Danych Ankietowych; Wydawnictwo AWF: Wrocław, Poland, 2015; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, J.; Gschwind, L. Three Generations of Telework, New ICTs and the (R)evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office. In Proceedings of the 17th ILERA World Congress, Cape Town, South Africa, 7–11 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dawidowicz, A.; Zysk, E.; Figurska, M.; Źróbek, S.; Kotnarowska, M. The methodology of identifying active aging places in the city. Cities 2020, 98, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat 2012. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/un-habitat-annual-report-2012 (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Koronawirus. RPO: Zakazy Wchodzenia do Lasu—Bez Podstawy Prawnej. Available online: https://bip.brpo.gov.pl/pl/content/koronawirus-rpo-brak-podstawy-prawnej-zakazu-wchodzenia-do-lasu (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Pineo, H.; Klonti, K.; Rutter, H.; Zimmermann, N.; Wilkinson, P.; Davies, M. Urban health indicator tools of the physical environment: A systematic review. J. Urban Health 2017, 95, 613–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shaheen, L.; All Ibrahim, M.A. Smart happy city. Sustain. City 2021, 253, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Ren, G. Impacts of COVID-19 on the usage of public bicycle share in London. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 150, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenu, N.; Dicaar-Sardarch, U.U. Bicycle and urban design. A lesson from COVID-19. The City Challenges And External Agents. Methods, Tools And Best Practices. J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2021, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poradnik Orange. Available online: https://www.orange.pl/poradnik/twoj-internet/internet-szerokopasmowy-co-to-znaczy/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Kardaś, A. Naukowców Niepokoi Niezwykle Szybkie Tempo Zmian Klimatu. 2018. Available online: https://www.teraz-srodowisko.pl/aktualnosci/naukowcow-niepokoi-niezwykle-szybkie-tempo-zmian-klimatu-5856.html (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Blunt, A.; Dowling, R. Home; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R.J. Health and Housing. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Smith, S., Ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewoc, M. Architektura i Urbanistyka w PRL—Co Się Udało, a co Niekoniecznie? 2019. Available online: https://www.morizon.pl/blog/architektura-i-urbanistyka-w-prl/ (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Grigoriadou, E.T. The urban balcony as the new public space for well-being in times of social distancing. Cities Health 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.; Ramos, N.M.M.; Flores-Colen, I. A review of balcony impacts on the indoor environmental quality of dwellings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Race, C. Triple Pane Window Benefits. 2019. Available online: https://craigrace.com/products-andmaterials-triple-pane-window/ (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Kesik, T.; O’Brien, L.; Peters, T. Enhancing the Livability and Resilience of Multi-Unit Residential Buildings: MURB Design Guide, Version 2.0. 2019. Available online: https://www.bchousing.org/publications/MURB-Design-Guide-V2.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Torrington, J.M.; Tregenza, P.R. Lighting for people with dementia. Lighting Res. Technol. 2007, 39, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.A.; Galasiu, A.D. The Physiological and Psychological Effects of Windows, Daylight, and View at Home: Review and Research Agenda; National Research Council Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiztegui, B. Green balconies: Gardens with altitude. ArchDaily. 2020. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/937886/green-balconies-gardens-with-altitude?ad_source5sea (accessed on 20 February 2022).

| Socio-Demographic Variables | n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | man | 84 | 42.0 |

| woman | 115 | 57.5 | |

| no response | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Age group | 18–24 | 50 | 25.0 |

| 25–34 | 48 | 24.0 | |

| 35–44 | 49 | 24.5 | |

| 45–54 | 38 | 19.0 | |

| 55–64 | 11 | 5.5 | |

| above 65 | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Employment status | employee/worker | 159 | 79.5 |

| student/schoolchild | 40 | 20.0 | |

| non-working | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Education | primary/vocational | 1 | 0.5 |

| secondary | 56 | 28.0 | |

| higher | 143 | 71.5 | |

| Marital status | single | 47 | 23.5 |

| single/child/children | 4 | 2.0 | |

| in a relationship/no children | 69 | 34.5 | |

| in a relationship/with children | 80 | 40.0 | |

| Place of residence region (voivodeship) | Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 10 | 5.0 |

| Dolnośląskie | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Lubelskie | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Lubuskie | 3 | 1.5 | |

| Łódzkie | 7 | 3.5 | |

| Małopolskie | 12 | 6.0 | |

| Mazowieckie | 26 | 13.0 | |

| Opolskie | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Podlaskie | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Podkarpackie | 29 | 14.5 | |

| Pomorskie | 10 | 5.0 | |

| Śląskie | 6 | 3.0 | |

| Świętokrzyskie | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 34 | 17.0 | |

| Wielkopolskie | 33 | 16.5 | |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 12 | 6.0 | |

| Characteristics of the place of residence location | city | 95 | 47.5 |

| urban periphery | 59 | 29.5 | |

| suburban area | 23 | 11.5 | |

| village | 7 | 3.5 | |

| rural periphery (dispersed mode of settlement) | 16 | 8.0 | |

| Housing type | a rented flat | 17 | 8.5 |

| flat/1 room | 15 | 7.5 | |

| flat/2 rooms | 43 | 21.5 | |

| flat/3 rooms | 46 | 23.0 | |

| flat/4 rooms and more | 13 | 6.5 | |

| terraced house | 7 | 3.5 | |

| semi-detached house | 9 | 4.5 | |

| detached house | 52 | 26.0 | |

| other | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Symbol | Factor Description |

|---|---|

| E1 | close proximity to the workplace |

| E2 | trendy location (prestige of the place) |

| E3 | easy access to small service facilities (greengrocer’s, grocer’s, chemist’s) |

| E4 | lots of greenery, squares, lawns |

| E5 | easy access to public transport (tram/bus/train) |

| E6 | close proximity to entertainment facilities (restaurants, pubs, etc.) |

| E7 | close proximity to school/kindergarten |

| E8 | safety of the neighbourhood/district |

| E9 | type of development |

| E10 | sentimental attachment to the neighbourhood |

| E11 | friends’/family members’ opinion on the location of the city/village/district |

| E12 | information on the planned development of the neighbourhood (investments) |

| E13 | proximity to a primary healthcare centre (outpatient clinic) |

| E14 | access to supermarket/hypermarket |

| E15 | access to parking spaces |

| E16 | access to leisure and sports facilities (e.g., football pitches) |

| E17 | appearance/aesthetics of the surrounding buildings |

| E18 | proximity to playgrounds, outdoor gyms, skateparks, etc. |

| E19 | accessibility of landscape architecture (benches, rubbish bins, fountains, monuments) |

| E20 | the condition of pavements, curbs, driveways, roadways |

| E21 | noise levels in the area |

| E22 | dispersed development |

| E23 | other |

| I1 | floor area of the flat |

| I2 | number of rooms |

| I3 | appearance/aesthetics of the building/façade |

| I4 | building construction technology (quality, lifespan) |

| I5 | building location (zone, district, etc.) |

| I6 | technical condition of the room/flat/house (utility systems, walls, floors, windows) |

| I7 | arrangement of rooms in the flat/house |

| I8 | presence of additional rooms (balcony, loggia, winter garden, shed, etc.) |

| I9 | good access to broadband Internet |

| I10 | brightness of rooms |

| I11 | the attractiveness of the view from the window |

| I12 | good thermal insulation of the building/flat/residential unit |

| I13 | good acoustic insulation of the building/flat/residential unit |

| I14 | access to digital platforms |

| I15 | energy-efficient equipment |

| I16 | running cost of the flat/apartment/house/residential unit |

| I17 | other |

| Description | Factor Symbol | Differences (%) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| close proximity to the workplace | E1 | −2.5 | 1.58 * |

| trendy location (prestige of the place) | E2 | −1.5 | 1.22 * |

| easy access to small service facilities (greengrocer’s, grocer’s, chemist’s) | E3 | −1.0 | 1.0 * |

| lots of greenery, squares, lawns | E4 | 6.0 | 2.46 * |

| easy access to public transport (tram/bus/train) | E5 | -9.0 | 3.0 ** |

| close proximity to entertainment facilities (restaurants, pubs, etc.) | E6 | −1.5 | 1.22 * |

| close proximity to school/kindergarten | E7 | −3.5 | 1.87 * |

| safety of the neighbourhood/district | E8 | −1.0 | 1.0 * |

| type of development | E9 | −3.5 | 1.87 * |

| sentimental attachment to the neighbourhood | E10 | −7.0 | 2.65 * |

| friends’/family members’ opinion on the location of the city/village/district | E11 | 2.5 | 1.58 * |

| information on the planned development of the neighbourhood (investments) | E12 | 2.5 | 1.58 * |

| proximity to a primary healthcare centre (outpatient clinic) | E13 | 8.0 | 2.83 ** |

| access to supermarket/hypermarket | E14 | −1.0 | 1.0 * |

| access to parking spaces | E15 | −1.0 | 1.0 * |

| access to leisure and sports facilities (e.g., football pitches) | E16 | 3.5 | 1.87 * |

| appearance/aesthetics of the surrounding buildings | E17 | −1.0 | 1.0 * |

| proximity to playgrounds, outdoor gyms, skateparks, etc. | E18 | −1.0 | 1.0 * |

| accessibility of landscape architecture (benches, rubbish bins, fountains, monuments) | E19 | 1.5 | 1.22 * |

| the condition of pavements, curbs, driveways, roadways | E20 | −1.5 | 1.22 * |

| noise levels in the area | E21 | -3.5 | 1.87 * |

| dispersed development | E22 | 6.5 | 2.55 * |

| other | E23 | 2.0 | 1.41 * |

| flat’s floor area | I1 | 12.0 | 3.46 ** |

| number of rooms | I2 | 14.5 | 3.80 ** |

| appearance/aesthetics of the building/façade | I3 | −6.5 | 2.56 * |

| building construction technology (quality, lifespan) | I4 | −3.0 | 1.73 * |

| building location (zone, district, etc.) | I5 | −4.5 | 2.12 * |

| technical condition of the room/flat/house (utility systems, walls, floors, windows) | I6 | −2.0 | 1.41 * |

| room arrangement | I7 | −1.0 | 1.0 * |

| presence of additional rooms (balcony, loggia, winter garden, shed, etc.) | I8 | 14.0 | 3.74 ** |

| good access to broadband Internet | I9 | 28.0 | 5.29 * |

| brightness of rooms | I10 | 7.0 | 2.65 * |

| the attractiveness of the view from the window | I11 | 7.0 | 2.65 * |

| good thermal insulation of the building/flat/residential unit | I12 | 5.0 | 2.24 * |

| good acoustic insulation of the building/flat/residential unit | I13 | 2.5 | 1.58 * |

| access to digital platforms | I14 | 9.5 | 3.08 ** |

| energy-efficient equipment | I15 | 3.5 | 1.87 * |

| running cost of the flat/apartment/house/residential unit | I16 | −4.5 | 2.12 * |

| other | I17 | −8.5 | 2.92 ** |

| df | 1 | ||

| p < 0.1 ** | 2.7055 | ||

| p < 0.05 * | 3.8415 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kocur-Bera, K. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Era on Residential Property Features: Pilot Studies in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095665

Kocur-Bera K. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Era on Residential Property Features: Pilot Studies in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095665

Chicago/Turabian StyleKocur-Bera, Katarzyna. 2022. "Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Era on Residential Property Features: Pilot Studies in Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095665