Patient’s Perspective of Telemedicine in Poland—A Two-Year Pandemic Picture

Abstract

:1. Introduction

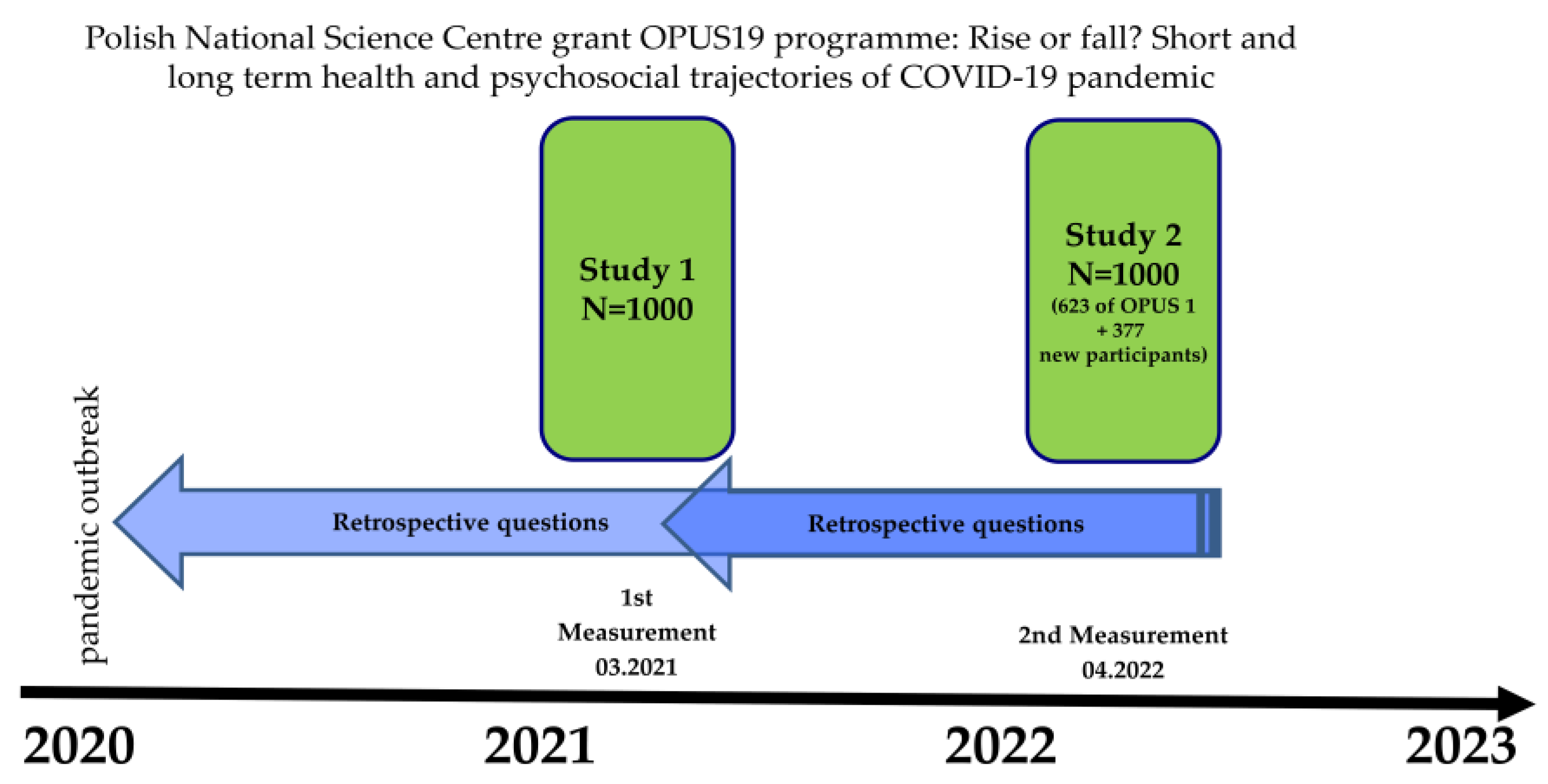

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Paparella, R.S.; Gentile, C.; Serpico, R.; Minervini, G.; Candotto, V.; Laino, L. How Social Media Meet Patients Questions: YouTube Review for Mouth Sores in Children. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.N.; Paparella, R.S.; Gentile, C.; Minervini, G.; Serpico, R.; Candotto, V.; Laino, L. How Social Media Meet Patients Questions: YouTube Review for Children Oral Thrush. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cruz, M.P.; Santos, E.; Cervantes, M.V.; Juárez, M.L. COVID-19, a Worldwide Public Health Emergency. Rev. Clínica Española 2021, 221, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlepa, K.; Śliwczyński, A.; Kamecka, K.; Kozłowski, R.; Gołębiak, I.; Cichońska-Rzeźnicka, D.; Marczak, M.; Glinkowski, W.M. The COVID-19 Pandemic as an Impulse for the Development of Telemedicine in Primary Care in Poland. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasani, S.A.; Ghafri, T.A.; Al Lawati, H.; Mohammed, J.; Al Mukhainai, A.; Al Ajmi, F.; Anwar, H. The Use of Telephone Consultation in Primary Health Care During COVID-19 Pandemic, Oman: Perceptions from Physicians. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 215013272097648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowada, C.; Sagan, A.; Kowalska-Bobko, I.; Badora-Musial, K.; Bochenek, T.; Domagala, A.; Dubas-Jakobczyk, K.; Kocot, E.; Mrozek-Gasiorowska, M.; Sitko, S.; et al. Poland: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2019, 21, 1–234. [Google Scholar]

- Lechowski, Ł.; Jasion, A. Spatial Accessibility of Primary Health Care in Rural Areas in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplaga, M. A Nationwide Natural Experiment of E-Health Implementation during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland: User Satisfaction and the Ease-of-Use of Remote Physician’s Visits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, G.; Russo, D.; Herford, A.S.; Gorassini, F.; Meto, A.; D’Amico, C.; Cervino, G.; Cicciù, M.; Fiorillo, L. Teledentistry in the Management of Patients with Dental and Temporomandibular Disorders. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 7091153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland’s Official Gazette. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/Isap.Nsf/ByYear.Xsp (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Telemedicine for Healthcare: Capabilities, Features, Barriers, and Applications. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kludacz-Alessandri, M.; Hawrysz, L.; Korneta, P.; Gierszewska, G.; Pomaranik, W.; Walczak, R. The Impact of Medical Teleconsultations on General Practitioner-Patient Communication during COVID- 19: A Case Study from Poland. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.S. Electronic Health Records: Then, Now, and in the Future. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2016, 25, S48–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaver, J. The State of Telehealth Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2022, 49, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashshur, R.L.; Howell, J.D.; Krupinski, E.A.; Harms, K.M.; Bashshur, N.; Doarn, C.R. The Empirical Foundations of Telemedicine Interventions in Primary Care. Telemed. E-Health 2016, 22, 342–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramsetty, A.; Adams, C. Impact of the Digital Divide in the Age of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1147–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payán, D.D.; Frehn, J.L.; Garcia, L.; Tierney, A.A.; Rodriguez, H.P. Telemedicine Implementation and Use in Community Health Centers during COVID-19: Clinic Personnel and Patient Perspectives. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, J.F.; Beard, M.; Kumar, S. Systematic Review of Patient and Caregivers’ Satisfaction with Telehealth Videoconferencing as a Mode of Service Delivery in Managing Patients’ Health. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The National Health Fund Report of the Satisfaction Survey of Patients Using Teleconsultation at Primary Medicine of Primary Care Physicians during the COVID-19 Epidemic. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/Attachment/A702e12b-8b16-44f1-92b5-73aaef6c165c (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Procontent Agency Report—How Do Poles Rate the Condition of Public Health Services in the COVID-19 Pandemic? Available online: https://www.procontent.pl/2022/01/Raport-Jak-Polacy-Oceniaja-Kondycje-Publicznej-Sluzby-Zdrowia-w-Pandemii-Covid-19/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Pappas, Y.; Seale, C. The Opening Phase of Telemedicine Consultations: An Analysis of Interaction. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeno, E.; Biesenbach, I.; Englund, C.; Lund, M.; Toft, A.; Lund, L. Patient Perspective on Telemedicine Replacing Physical Consultations in Urology during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Denmark. Scand. J. Urol. 2021, 55, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maese, J.R.; Seminara, D.; Shah, Z.; Szerszen, A. Perspective: What a Difference a Disaster Makes: The Telehealth Revolution in the Age of COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2020, 35, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, A.; Valdovinos, C.; Wang, E.; Abhat, A.; Mendez, C.; Gutierrez, G.; Portz, J.; Brown, A.; Lyles, C.R. Perspectives from Leadership and Frontline Staff on Telehealth Transitions in the Los Angeles Safety Net during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 944860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiria Perez, G.; Cruess, D. The Impact of Familism on Physical and Mental Health among Hispanics in the United States. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlepa, K.; Tenderenda, A.; Kozłowski, R.; Marczak, M.; Wierzba, W.; Śliwczyński, A. Recommendations for the Development of Telemedicine in Poland Based on the Analysis of Barriers and Selected Telemedicine Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchell, R.; Locatis, C.; Burgess, G.; Maisiak, R.; Liu, W.-L.; Ackerman, M. Patient and Provider Satisfaction with Teledermatology. Telemed. E-Health 2017, 23, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patient Ombudsman Report: Patients’ Problems during the COVID-19 Epidemic. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/Web/Rpp/Problemy-Pacjentow-w-Obliczu-Epidemii-Covid-19 (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Schinasi, D.A.; Foster, C.C.; Bohling, M.K.; Barrera, L.; Macy, M.L. Attitudes and Perceptions of Telemedicine in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey of Naïve Healthcare Providers. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 647937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, P.S.; Mackert, M.S. Addressing Telehealth’s Foremost Barrier: Provider as Initial Gatekeeper. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2005, 21, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Morilla, M.D.; Sans, M.; Casasa, A.; Giménez, N. Implementing Technology in Healthcare: Insights from Physicians. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, A.Y.; Choi, W.S. Considerations on the Implementation of the Telemedicine System Encountered with Stakeholders’ Resistance in COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed. E-Health 2021, 27, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.; Sanchez-Vazquez, A.; Ivory, C. Clinicians’ Role in the Adoption of an Oncology Decision Support App in Europe and Its Implications for Organizational Practices: Qualitative Case Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e13555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otto, L.; Harst, L. Investigating Barriers for the Implementation of Telemedicine Initiatives: A Systematic Review of Reviews. In Proceedings of the 25th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS, Cancún, Mexico, 15–17 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, J.H.M.; McGregor, A.H. Body-Worn Sensor Design: What Do Patients and Clinicians Want? Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 39, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.; Khalil, S.; Kamath, M.; Wilhalme, H.; Lewis, A.; Moore, M.; Nsair, A. Evaluating Factors of Greater Patient Satisfaction with Outpatient Cardiology Telehealth Visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cardiovasc. Digit. Health J. 2021, 2, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekaran, K. Access to Telemedicine—Are We Doing All That We Can during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 163, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolahi, A.; Bull, M.T.; Darwin, K.C.; Venkataraman, V.; Grana, M.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Biglan, K.M. A Feasibility Study of Conducting the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Remotely in Individuals with Movement Disorders. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.; Brewster, R.; Newman, J.G.; Rajasekaran, K. Optimizing Your Telemedicine Visit during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Practice Guidelines for Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Head Neck 2020, 42, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables N (% of N in a Row) | Frequency of Telemedicine Use during 2 Years of the Pandemic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely (1 or 2 Times) | Regular (at Least 3 Times) | Total | p-Value * | ||

| N = 136 | N = 293 | N = 194 | N = 623 | |||

| Gender | female | 58 (18.3) | 153 (48.3) | 106 (33.4) | 317 | 0.082 |

| male | 78 (25.5) | 140 (45.8) | 88 (28.8) | 306 | ||

| Age | 18–24 | 10 (31.3) | 18 (56.3) | 4 (12.5) | 32 | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 29 (31.5) | 52 (56.5) | 11 (12.0) | 92 | ||

| 35–44 | 34 (28.8) | 52 (44.1) | 32 (27.1) | 118 | ||

| 45–54 | 23 (27.4) | 33 (39.3) | 28 (33.3) | 84 | ||

| 55–64 | 23 (17.8) | 58 (45.0) | 48 (37.2) | 129 | ||

| 65+ | 17 (10.1) | 80 (47.6) | 71 (42.3) | 168 | ||

| Education | lower | 70 (32.0) | 92 (41.4) | 60 (27.0) | 222 | <0.001 |

| middle | 40 (18.0) | 105 (47.5) | 76 (34.4) | 221 | ||

| higher | 26 (14.0) | 96 (53.3) | 58 (32.2) | 180 | ||

| City size | village/rural | 56 (25.0) | 112 (50.0) | 56 (25.0) | 224 | 0.042 |

| city/town up to 100,000 | 44 (21.0) | 81 (39.5) | 80 (39.0) | 205 | ||

| city/town of 100–500,000 | 22 (19.0) | 60 (52.6) | 32 (28.1) | 114 | ||

| city/town of more than 500,000 | 14 (18.0) | 40 (50.0) | 26 (32.5) | 80 | ||

| Item-Opinion on Telemedicine | p-Value * | Pairwise Comparisons ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never vs. Once | Never vs. Twice | Once vs. Twice | ||

| effective | 0.063 | sig. | ||

| time saving | 0.005 | sig. | sig. | |

| insight into medical history | 0.012 | sig. | sig. | |

| high level of care | 0.631 | |||

| minimal risk of not detecting disease | 0.982 | |||

| good systemic solution | 0.004 | sig. | sig. | |

| availability of doctor appointment | 0.559 | sig. | sig. | |

| average opinion in 2021 | 0.002 | sig. | sig. | |

| Item-Opinion on Telemedicine | p-Value * | Pairwise Comparisons ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never vs. Rarely | Never vs. Regular | Rarely vs. Regular | ||

| effective | <0.001 | sig. | sig. | sig. |

| time saving | <0.001 | sig. | sig. | |

| insight into medical history | <0.001 | sig. | sig. | |

| high level of care | 0.004 | sig. | sig. | |

| minimal risk of not detecting disease | 0.321 | |||

| good systemic solution | 0.091 | sig. | ||

| availability of doctor appointment | <0.001 | sig. | sig. | sig. |

| average opinion in 2022 | 0.011 | sig. | sig. | |

| Variables | Category/Values | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis (Model R2 = 0.082) | VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | |||

| Gender | male | 0.012 | 0.766 | 0.021 | 0.596 | 1.014 |

| Age | [years] | 0.167 | <0.001 | 0.100 | 0.020 | 1.175 |

| Education | [lower = 1 to higher = 3] | 0.040 | 0.330 | −0.016 | 0.707 | 1.121 |

| City size | [rural = 1 to over 500 k = 4] | −0.023 | 0.572 | −0.063 | 0.123 | 1.063 |

| Telemedicine frequency | [never = 0 to regular = 2] | 0.201 | <0.001 | 0.159 | <0.001 | 1.079 |

| Vaccinated against COVID-19 | [yes = 1] | −0.195 | <0.001 | −0.149 | <0.001 | 1.149 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sołomacha, S.; Sowa, P.; Kiszkiel, Ł.; Laskowski, P.P.; Alimowski, M.; Szczerbiński, Ł.; Szpak, A.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; Kamiński, K. Patient’s Perspective of Telemedicine in Poland—A Two-Year Pandemic Picture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010115

Sołomacha S, Sowa P, Kiszkiel Ł, Laskowski PP, Alimowski M, Szczerbiński Ł, Szpak A, Moniuszko-Malinowska A, Kamiński K. Patient’s Perspective of Telemedicine in Poland—A Two-Year Pandemic Picture. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleSołomacha, Sebastian, Paweł Sowa, Łukasz Kiszkiel, Piotr Paweł Laskowski, Maciej Alimowski, Łukasz Szczerbiński, Andrzej Szpak, Anna Moniuszko-Malinowska, and Karol Kamiński. 2023. "Patient’s Perspective of Telemedicine in Poland—A Two-Year Pandemic Picture" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010115

APA StyleSołomacha, S., Sowa, P., Kiszkiel, Ł., Laskowski, P. P., Alimowski, M., Szczerbiński, Ł., Szpak, A., Moniuszko-Malinowska, A., & Kamiński, K. (2023). Patient’s Perspective of Telemedicine in Poland—A Two-Year Pandemic Picture. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010115