Towards an Evidence-Based Model of Workplace Postvention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- informing staff about working effectively with clients/customers/colleagues bereaved by suicide; and

- supporting employees with the impact of work that exposes them to suicide and suicide-related bereavement.

- ○

- What was the experience of funeral staff with funerals due to suicide?

- ○

- What was their response to a bespoke postvention training program [28] (see ‘Training’ designed with and for staff to assist them in this work?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Training

2.3. Online Questionnaires

2.4. Semi-Structured Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Baseline and Post-Training Questionnaires

3.3. Post-Training Questionnaire Results

3.4. Semi-Structured Interviews—Thematic Analysis

- Theme 1: Work & Role

- Theme 2: Engagement

- Theme 3: Emotionality

Funeral Conductor:“Everyone’s got a section to bring that funeral together. For instance, the mortuary staff, they want to try and present that person … to make sure that is the best possible memory that you can have because some people get very damaged. So, there’s only so much you can do. The [Funeral Arranger] [puts] together the type of funeral that the family want at the location that they want, with everything involved in the funeral that they want, and then that gets handed on to the Conductor to make it happen on the day. The [Funeral Director’s Assistants] want to make sure that they’re there if they’re needed to assist. They want to make sure they’re on time. They want to make sure that they’re efficient. They want to make sure that they can do whatever around the family that needs to be done so it brings it all together. The Conductor, he [sic] wants to make sure the family are aware, or somebody around the family can guide the family [through the service], so that they know where they’re going. They know what’s going to happen next. You [as a Funeral Conductor] need to be able to flow it through.”

Manager/Funeral Arranger:“The [staff at the funeral service] have a different sort of role particularly for a young person. [They are] dealing with obviously an incredibly grief-stricken family. The kids coming to the funeral are very emotional too [and] quite frankly they don’t quite know how to behave. There’s nothing in their skill set that’s given them any tools to know how to behave when they’ve lost someone close.”

Funeral Conductor:“It’s more about the sensitivity of it … it’s about managing their expectations of what they’re going to see when they come and have a viewing. It is a conversation we have to have again and again. Sometimes it is about guidance and sometimes it is about just saying ‘I actually think this is not going to be in your best interests and this is why.’ Ultimately, it’s always going to be their decision. But you have to guide them, I think, at some stage and I’m comfortable with that. People come to us because we are the professionals and we know what we are doing.”

Funeral Arranger:“The families are often traumatised and shell-shocked. So, it’s a very different feeling in the [Arrangement meeting] in comparison, say, to someone organising a funeral for their 90-year-old mother who’s had a long and fruitful life. Often, they can’t even articulate anything. There is just raw grief and emotion in the room and it’s hard to have a meeting like that. It’s a very long, drawn out couple of hours. It’s quite draining as well, from both sides, I think.”

Funeral Conductor:“Look, a suicide has that extra layer because it was, for want of a better word, self-inflicted. Right? Whereas an accident they’re like—it’s still shocking. It’s sudden but it’s no fault of anyone. Do you know what I mean? It wasn’t purposely done. But the family is still in that situation where they’re—they’re in a situation they never thought they’d be in. They’ve been thrown into this situation and it’s the last place they want to be to me. So, it’s a very different feeling.”

Funeral Conductor:“What I mean by the eggshells…[is that] you’ve just got to be careful. You really have got to have a look at the people in the family. You really have got to listen to what they do or don’t say. That can be a little bit eggshelly [sic]. That really can be. We might need to calm people down and we might need to take people out of the room because somebody just needs to vent, if you like. You get people come in when there’s been a suicide and they’re angry. And you have got to deal with that when it walks in that door. You’re the one that’s facing it.”

Funeral Director’s Assistant:“[At a suicide bereavement funeral] I get a sense of a real kind of ‘What do you say?’ ‘What do you do?’ You can read it on people’s faces, they want to talk about it. You hear all the whispers. As opposed to somebody who’s died of natural causes. ‘Oh, she had a great life.’ And it’s a great celebration of life for them. It’s a much happier mood at a funeral, if there’s such a thing. As opposed to—I think suicide is confusing, because people are still coming to terms.”

Funeral Arranger:“In my experience families have just wanted to get it over and done with. They know they just have to do this arrangement. They just want it done. And they want to get out of there pretty quickly. They don’t want it to drag on. Because they’ve been thrown into the situation, they haven’t had time to think about what they would have liked to have done for a funeral. Whereas in other [expected] funerals I’ve had people wait two weeks because they want time to get it perfect. But with a suicide it seems everything is quite rushed.”

Administrative Staff:“We’re more aware of language [when working with suicide] and I use the term ‘taking their own life’ [which] I think is a much nicer way of saying it. It doesn’t have quite as harsh an impact upon a person, I think.”

Manager/Funeral Arranger:“It’s that delicate use of language and nuances and I’m always learning new ways of doing that. I will spend time pondering and working on the language…I like to have ways that I can discuss things without stumbling because I don’t think that’s kind and these people need us to be kind—honest but kind, not kind and unfaithful to the process.

Manager/Funeral Arranger:“There seems to be a degree of secrecy on the part of the family. Some of the families will state clearly what the cause of death was; suicide families might not so openly. Sometimes it comes up at some stage later when they relax. I never ask questions…But you can kind of sense it.”

Funeral Arranger:“If someone passes away, they [a family bereaved by suicide] might of sort of say ‘he was found here.’ And you get this indication that you don’t want to go probing too much, because it seems like you’re doing it for just being nosy in a way. So yeah, people can be a little bit closed off and don’t really give much information.”

Manager/Funeral Arranger:“It [working on a suicide bereavement funeral] is more difficult for everyone emotionally.”

Funeral Arranger:“The emotional intensity seems to be there quite strong, more so than with other funerals.”

Mortuary Staff:“I guess that’s one of our problems, as well. We get a little bit emotionally invested in a deceased person…especially with a young person, we just want them to look their absolute best. And we will beat ourselves up about and go above and beyond.”

Funeral Arranger:“I was doing that. I was taking it away: I was feeling this could happen to me. What if this happens to my children. And you come away feeling quite low as well, hoping that it would never—that you’re never in that situation either.”

Administrative Staff:“I think it’s just, you know, it’s a tragic end to a life. It was an unexpected end to a life. So, I think that’s why we kind of want to do our best for that person. Just a little bit more because you know that the family are really going to be grieving.”

Manager/Funeral Arranger:“You sit with a family and you’re basically crushing their dreams because they had hopes and dreams for their loved one and you’re sitting there going, ‘So, we’re just going to look at a coffin now.’ And that’s just—you’re just a bearer of bad news and you talk about grave debts [cemetery fees] and they just look at you like this is the last thing they want to be doing today and sometimes you are the worst person in the world because you are forcing them to consider things that they never in their wildest dreams ever thought they would have to consider.”

Funeral Arranger:“There’s a level…that’s where you’ve got to make sure that you’ve got that, say, level you can go so far, engage yourself to a certain level but then you’ve also got to make sure that you’re taking a step back a little bit to make sure—because otherwise you can take everything home with you and it can play on your own mind as well.”

Funeral Conductor:“You hear it’s a suicide and then—so yes, you do think, ‘Well, hang on a minute’. Okay, so you do pull back a little bit. You want a little bit—you want to try and get as much information as you can, but [also to] just to maybe prepare yourself for the family. Because you don’t know what you’re going to get. And you know why that is? It’s probably—and I mean I don’t even know if this is true because maybe it’s just the way that—after doing so many funerals. It’s the fact that it wasn’t an illness, and it wasn’t expected, and no one knew this was going to happen. It was suicide. It is different. It just is. It just is. So we need to just remember that. We need to prepare ourselves.”

Manager/Funeral Arranger:“I think these jobs and this profession is prone to burnout. The people who are not looking after themselves by stepping up and switching off they really burn out and they either—they usually quit the job or step down from the role or something.”

Mortuary Staff:“My job is dangerous, not from a physical aspect, but from an emotional and mental aspect as well. If you don’t deal with it, you don’t—if you can’t process those—if you hold on to things like that, it can damage you. You know? And that’s something that—you see people who’ve worked in the industry for a couple of years, you see little cracks appearing in personality, how they deal stuff, attitudes.”

3.5. Responses to the Training

Funeral Arranger:“My journey with suicide has probably matched with a lot of people in the community. It took me years and just experience, and [the] Training got my head around to the space that that’s their right, it is their own life and sometimes it’s the only alternative they can consider. So, who am I to judge that?”

Funeral Arranger:“I think [post-Training] there is far more openness [about working with suicide bereavement funerals] which is very healthy for everyone.

Manager:“What we didn’t do well for years is to highlight to staff that they are going to a funeral for somebody who has taken their own life. I was told when I started that it was none of our business and that had all sorts of issues tied into it because suicide was still a taboo, and some families didn’t want you to know. I do it [inquire about if the loss might be due to suicide] much more comfortably now because of the [Working Well with Suicide Bereavement Funerals] Training.”

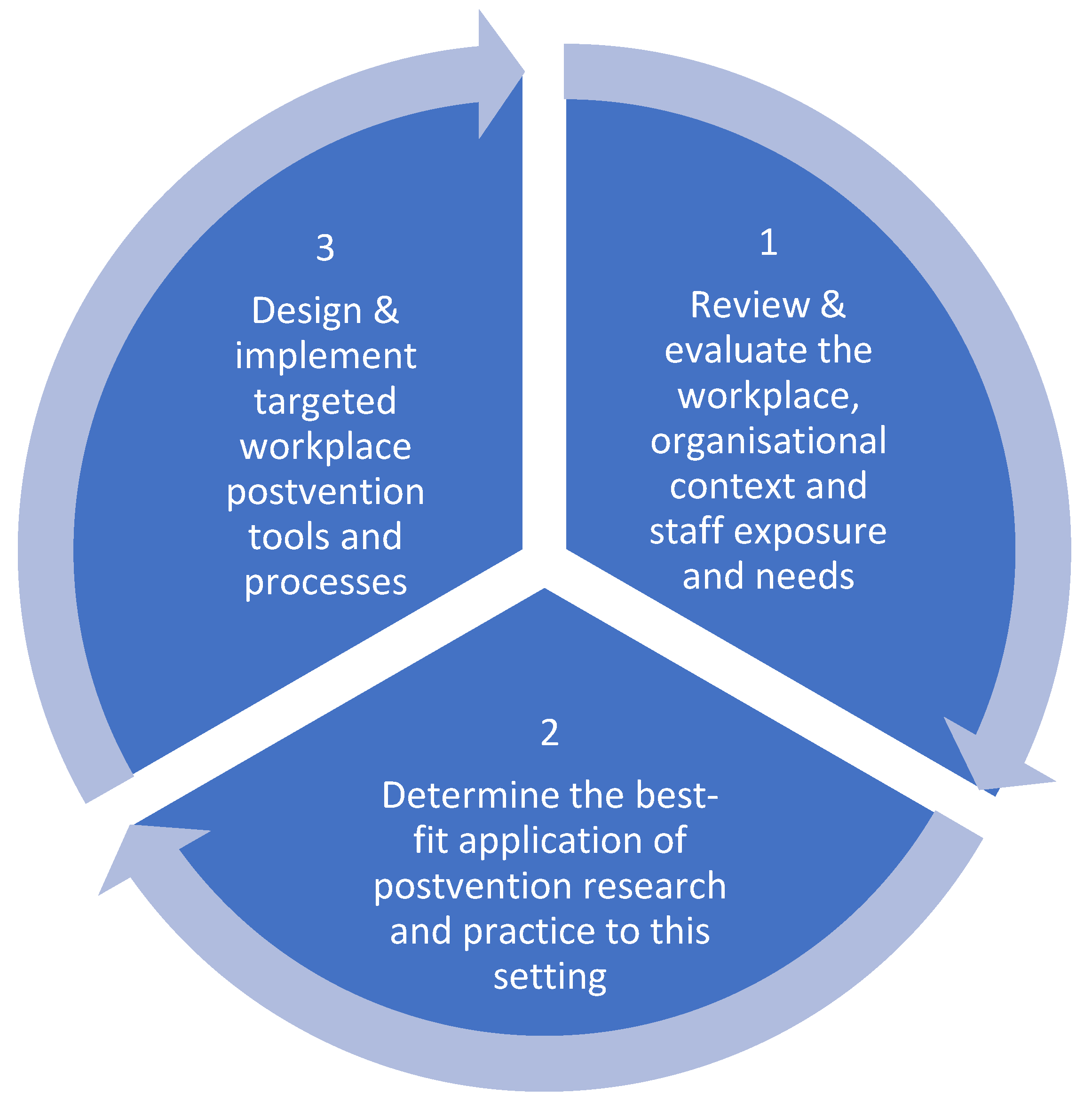

3.6. A Model of Workplace Postvention

- Understanding workplace and staff needs in the context in which they operate;

- Applying postvention research and practice to address identified needs;

- Delivering bespoke postvention components (training, governance, resources and integration/networks) to support preparedness and responsivity; and

- Implementation of ongoing research and evaluation for organisational and program improvement.

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ross, V.; Kolves, K.; De Leo, D. Exploring the Support Needs of People Bereaved by Suicide: A Qualitative Study. OMEGA 2021, 82, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention & Postvention Australia. Postvention Australia Guidelines: A Resource for Organisations and Individuals Providing Services to People Bereaved by Suicide; Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention: Brisbane, Australia, 2017; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Andriessen, K. Can postvention be prevention? Crisis 2009, 30, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.M.; Kim, Y.; Prigerson, H.G.; Mortimer-Stephens, M. Complicated grief in survivors of suicide. Crisis 2004, 25, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maple, M.; Sanford, R.; Pirkis, J.; Reavley, N.; Nicholas, A. Exposure to suicide in Australia: A representative random digit dial study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, K.; Krysinska, K.; Rickwood, D.; Pirkis, J. “It Changes Your Orbit”: The Impact of Suicide and Traumatic Death on Adolescents as Experienced by Adolescents and Parents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, A. Postvention: A Case Study with Funeral Staff. Master’s Thesis, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Farberow, N. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2005, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Malkina-Pykh, I. Associations of Burnout, Secondary Traumatic Stress and Individual Differences among Correctional Psychologists. J. Forensic Sci. Res. 2017, 1, 018–034. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel, N.A.; Pennington, M.L.; Cammarata, C.M.; Leto, F.; Ostiguy, W.J.; Gulliver, S.B. Is Cumulative Exposure to Suicide Attempts and Deaths a Risk Factor for Suicidal Behavior Among Firefighters? A Preliminary Study. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2016, 46, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanford, R.L.; Hawker, K.; Wayland, S.; Maple, M. Workplace exposure to suicide among Australian mental health workers: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.A.; Cordingley, L.; Kapur, N.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Shaw, J.; Smith, S.; McGale, B.; McDonnell, S. ‘We’re the First Port of Call’—Perspectives of Ambulance Staff on Responding to Deaths by Suicide: A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seguin, M.; Bordeleau, V.; Drouin, M.S.; Castelli-Dransart, D.A.; Giasson, F. Professionals’ reactions following a patient’s suicide: Review and future investigation. Arch. Suicide Res. 2014, 18, 340–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halligan, P.; Corcoran, P. The impact of patient suicide on rural general practitioners. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2001, 51, 295–296. [Google Scholar]

- Foggin, E.; McDonnell, S.; Cordingley, L.; Kapur, N.; Shaw, J.; Chew-Graham, C.A. GPs’ experiences of dealing with parents bereaved by suicide: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e737–e746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.; Brand, F.; Carbonnier, A.; Croft, A.; Lascelles, K.; Wolfart, G.; Hawton, K. Effects of patient suicide on psychiatrists: Survey of experiences and support required. BJPsych Bull. 2019, 43, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudd, R.A.; D’Andrea, L.M. Compassionate Detachment: Managing Professional Stress While Providing Quality Care to Bereaved Parents. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2015, 30, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, S.; Nelson, P.A.; Leonard, S.; McGale, B.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Kapur, N.; Shaw, J.; Smith, S.; Cordingley, L. Evaluation of the Impact of the PABBS Suicide Bereavement Training on Clinicians’ Knowledge and Skills. Crisis 2020, 41, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baldwin, G.; Butler, H.; Hannaway, M.; headspace School Support. Delivering Effective Suicide Postvention in Australian School Communities; headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Australia, Suicide Prevention: A Competency Framework. 2021. Available online: https://www.suicidepreventionaust.org/competency-framework/ (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Mental Health Commission of NSW. Strategic Framework for Suicide Prevention in NSW 2018–2023; Mental Health Commission of NSW Sydney: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. Victorian Suicide Prevention Framework 2016–2025; Victorian Department of Health and Human Services: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2016.

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Evaluation of Suicide Prevention Activities. 2014. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/suicide-prevention-activities-evaluation~Appendices~appendixe~results (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Life in Mind, Priority Populations (ABS and AIHW) 19.11.22. Available online: https://lifeinmind.org.au/about-suicide/priority-populations (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- SafeWork Australia. Home Services: Mental Health. 2020. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/covid-19-information-workplaces/industry-information/home-services/mental-health (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Chandler, D.; Munday, R. Oxford: A Dictionary of Media and Communication, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100109997 (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Aoun, S.M.; Lowe, J.; Christian, K.M.; Rumbold, B. Is there a role for the funeral service provider in bereavement support within the context of compassionate communities? Death Stud. 2019, 43, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neami National. Working Well with Suicide Bereavement Funerals; Neami National: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Levers, M.-J.D. Philosophical Paradigms, Grounded Theory, and Perspectives on Emergence. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 2158244013517243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoschschild, A.R. The Managed Heart: Commercialisation of Human Feeling, 3rd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Szumilas, M.; Kutcher, S. Systematic Review of Suicide Postvention Programs for Nova Scotia Department of Health Promotion and Protection; Nova Scotia Department of Health Promotion and Protection: New Glasgow, NS, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andriessen, K.; Krysinska, K.; Kõlves, K.; Reavley, N. Suicide Postvention Service Models and Guidelines 2014–2019: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, I.T.; Iglewicz, A.; Glorioso, D.; Lanouette, N.; Seay, K.; Ilapakurti, M.; Zisook, S. Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.L.; Rantell, K.; Moran, P.; Sireling, L.; Marston, L.; King, M.; Osborn, D. Support received after bereavement by suicide and other sudden deaths: A cross-sectional UK study of 3432 young bereaved adults. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Causer, H.; Spiers, J.; Efstathiou, N.; Aston, S.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Gopfert, A.; Grayling, K.; Maben, J.; van Hove, M.; Riley, R. The Impact of Colleague Suicide and the Current State of Postvention Guidance for Affected Co-Workers: A Critical Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, T.; Patel, A.B. Client suicide: What now? Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Mancinelli, I.; Tatarelli, R. Stigma as a cause of suicide. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, K. Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Hidden Sorrow; Lexington Books: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, W.E. Handling the stigma of handling the dead: Morticians and funeral directors. Deviant Behav. 1991, 12, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Health Practitioner Board. Psychology Board of Australia Registration Standards; Australian Health Practitioner Board: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2022.

| Variable | Less than Other Funerals No. (%) | Same as Other Funerals No. (%) | Greater than Other Funerals No. (%) | Not Worked on Suicide Bereavement Funeral No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of difficulty | 0 (0) | 14 (20.9) | 50 (74.6) | 3 (4.5) |

| Emotional impact on other staff | 0 (0) | 25 (37.3) | 42 (62.7) | - |

| Emotional impact on self | 0 (0) | 26 (38.8) | 38 (56.7) | 3 (4.5) |

| Difficulty finding the right words to use | 0 (0) | 11 (16.4) | 52 (77.6) | 4 (6) |

| Overall confidence | 11 (16.4) | 49 (73.1) | 7 (10.5) | - |

| Overall comfort | 18 (27) | 43 (64.2) | 6 (9) | - |

| Variable | No Change No.% | Somewhat Useful No.% | Very Useful No.% |

|---|---|---|---|

| The training and resources have been useful in working with suicide bereavement funerals * | - | 14 (43.8) | 17 (53.1) * |

| The training and resources have helped you better understand the emotional impact of working with suicide bereavement funerals | - | 16 (50) | 15 (46.9) |

| The training and resources helped you better manage the emotional impact of working with suicide bereavement funerals | 3 (9.4) | 16 (50) | 12 (38) |

| The training and resources helped reduce the amount of pressure you feel working with suicide bereavement funerals | 14 (43.8) | 15 (46.9) | 2 (6.3) |

| Following the training, please rate your level of confidence that you know/use appropriate language working with suicide bereavement funerals | 4 (13) | 15 (46.9) | 12 (38) |

| Please rate your awareness, following the training of suicide bereavement and support services | 3 (9.4) | 13 (40.6) | 14 (44) |

| Please rate your level of comfort, following the training, in sharing resources about suicide bereavement support services with families and mourners | 1 (3.1) | 21 (65.6) | 9 (28.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Clements, A.; Nicholas, A.; Martin, K.E.; Young, S. Towards an Evidence-Based Model of Workplace Postvention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010142

Clements A, Nicholas A, Martin KE, Young S. Towards an Evidence-Based Model of Workplace Postvention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010142

Chicago/Turabian StyleClements, Alison, Angela Nicholas, Karen E Martin, and Susan Young. 2023. "Towards an Evidence-Based Model of Workplace Postvention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010142

APA StyleClements, A., Nicholas, A., Martin, K. E., & Young, S. (2023). Towards an Evidence-Based Model of Workplace Postvention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010142