Can Physical, Psychological, and Social Vulnerabilities Predict Ageism?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Social Identity Theory

1.2. Vulnerability in Old Age

1.3. Vulnerable Life Situations

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iversen, T.N.; Larsen, L.; Solem, P.E. A conceptual analysis of Ageism. Nord. Psychol. 2009, 61, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiovitz-Ezra, S.; Shemesh, J.; McDonnell, M. Pathways from ageism to loneliness. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism; Ayalon, L., Tesch-Römer, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bodner, E.; Palgi, Y.; Wyman, M.F. Ageism in Mental Health Assessment and Treatment of Older Adults. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wyman, M.F.; Shiovitz-Ezra, S.; Bengel, J. Ageism in the health care system: Providers, patients, and systems. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Chang, E.-S.; Kannoth, S.; Wang, S.-Y. Ageism Amplifies Cost and Prevalence of Health Conditions. Gerontologist 2018, 60, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muntsant, A.; Ramírez-Boix, P.; Leal-Campanario, R.; Alcaín, F.J.; Giménez-Llort, L. The Spanish Intergenerational Study: Beliefs, Stereotypes, and Metacognition about Older People and Grandparents to Tackle Ageism. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkoçak, V.; Özdemir, F. Age-Related Changes in the External Noses of the Anatolian Men. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2018, 42, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Faulkner, J.; Schaller, M. Evolved Disease-Avoidance Processes and Contemporary Anti-Social Behavior: Prejudicial Attitudes and Avoidance of People with Physical Disabilities. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2003, 27, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.A.; Schaller, M. Prejudicial Attitudes Toward Older Adults May Be Exaggerated When People Feel Vulnerable to Infectious Disease: Evidence and Implications. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2009, 9, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.T.; Metzger, A. College Students’ Ageist Behavior: The Role of Aging Knowledge and Perceived Vulnerability to Disease. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2013, 34, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R.; Sánchez-Izquierdo, M. Health, Psycho-Social Factors, and Ageism in Older Adults in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.; Vura, N.V.R.K.; Gravenstein, S. COVID-19 in older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, Z.; Kalayanamitra, R.; McClafferty, B.; Kepko, D.; Ramgobin, D.; Patel, R.; Aggarwal, C.S.; Vunnam, R.; Sahu, N.; Bhatt, D.; et al. COVID-19 and older adults: What we know. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergman, Y.S.; Cohen-Fridel, S.; Shrira, A.; Bodner, E.; Palgi, Y. COVID-19 health worries and anxiety symptoms among older adults: The moderating role of ageism. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1371–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madran, H.D. Ayrımcılığa Covid-19 Sürecinden Bir Bakış: Temel Kuramlar, Yaşçılık Tartışmaları ve Öneriler. Connect. Istanb. Univ. J. Commun. Sci. 2021, 60, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, H.J.; Chasteen, A.L. Ageism in the time of COVID-19. Group Processes Intergroup Relat. 2021, 24, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.E. Risk factors for elder abuse and neglect: A review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 50, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, I.S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Newton, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kite, M.E.; Wagner, L.S. Attitudes toward older adults. In Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice Against Older Persons; Nelson, T.D., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 129–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bodner, E.; Bergman, Y.S.; Cohen-Fridel, S. Different dimensions of ageist attitudes among men and women: A multigenerational perspective. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rogers, W.; MacKenzie, C.; Dodds, S. Why bioethics needs a concept of vulnerability. IJFAB: Int. J. Fem. Approaches Bioeth. 2012, 5, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklehurst, H.; Laurenson, M. A concept analysis examining the vulnerability of older people. Br. J. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1354–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, T.L.; Inker, J.; Welleford, E.A. A Theory of Relational Ageism: A Discourse Analysis of the 2015 White House Conference on Aging. Gerontologist 2017, 58, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; Powell, J. Old age, vulnerability and sexual violence: Implications for knowledge and practice. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2006, 53, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, L.E.; Busey, T.A.; Craig, J.; Kewley-Port, D. Are age-related changes in cognitive function driven by age-related changes in sensory processing? Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2012, 75, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrzus, C.; Hänel, M.; Wagner, J.; Neyer, F.J. Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, T.D. Ageism: Prejudice Against Our Feared Future Self. J. Soc. Issues 2005, 61, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrum, T.; Solomon, P.L. Elder Mistreatment Perpetrators with Substance Abuse and/or Mental Health Conditions: Results from the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Psychiatr. Q. 2017, 89, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, K.J.; Liu, P.-J.; Iris, M. Examining the Role of Substance Abuse in Elder Mistreatment: Results from Mistreatment Investigations. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 34, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajuhinia, S.; Faraji, R. P27: Explanation of vulnerability to somatization and anxiety based on attachment styles. Neuro Sci. J. Shefaye Khatam 2014, 2, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, O.; Park, S.; Kang, J.Y.; Kwak, M. Types of multidimensional vulnerability and well-being among the retired in the U.S. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 1361–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.P. An overview of clinical considerations and principles in the treatment of PTSD. In Treating Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Friedman, M.J., Lindy, J.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, M.S.; Russell, B.S.; Finan, L.J. The Influence of Parental Support and Community Belonging on Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Substance Use over Time. Subst. Use Misuse 2019, 55, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.H.; Hessling, R.M.; Russell, D.W. Social support, health, and well-being among the elderly: What is the role of negative affectivity? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavri, S. Loneliness: The Cause or Consequence of Peer Victimization in Children and Youth. Open Psychol. J. 2015, 8, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-15: Validity of a New Measure for Evaluating the Severity of Somatic Symptoms. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Canuto, A.; Weber, K.; Baertschi, M.; Andreas, S.; Volkert, J.; Dehoust, M.C.; Sehner, S.; Suling, A.; Wegscheider, K.; Ausín, B.; et al. Anxiety Disorders in Old Age: Psychiatric Comorbidities, Quality of Life, and Prevalence According to Age, Gender, and Country. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutepfa, M.M.; Motsamai, T.B.; Wright, T.C.; Tapera, R.; Kenosi, L.I. Anxiety and somatization: Prevalence and correlates of mental health in older people (60+ years) in Botswana. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, K.; Mercer, S.W.; Norbury, M.; Watt, G.; Wyke, S.; Guthrie, B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012, 380, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dyk, S.; Lessenich, S.; Denninger, T.; Richter, A. The many meanings of “active ageing”. Confronting public discourse with older people’s stories. Rech. Sociol. Anthropol. 2013, 44, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5); US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for PTSD: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, C.; Barnow, S.; Völzke, H.; John, U.; Freyberger, H.J.; Grabe, H.J. Trauma, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Physical Illness: Findings from the General Population. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, J.O.E.; Goldsmith, A.A.; Lemmer, J.A.; Kilmer, M.T.; Baker, D.G. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and health-related quality of life in OEF/OIF veterans. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 21, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, X.; Lou, C.; Sonenstein, F.L.; Kalamar, A.; Jejeebhoy, S.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Brahmbhatt, H.; Olumide, A.; Ojengbede, O. The Association Between Social Support and Mental Health Among Vulnerable Adolescents in Five Cities: Findings From the Study of the Well-Being of Adolescents in Vulnerable Environments. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, S31–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brewin, C.R.; Andrews, B.; Valentine, J.D. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.S.; Morey, M.C.; Beckham, J.C.; Bosworth, H.B.; Sloane, R.; Pieper, C.F.; Pebole, M.M. Warrior Wellness: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial of the Effects of Exercise on Physical Function and Clinical Health Risk Factors in Older Military Veterans With PTSD. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2019, 75, 2130–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, A.; Graham, C. Subjective wellbeing in Colombia: Some insights on vulnerability, job security, and relative incomes. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2013, 1, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T. Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 1068–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, M.L.; Kaufmann, C.N.; Palmer, B.W.; Depp, C.A.; Martin, A.S.; Glorioso, D.K.; Thompson, W.K.; Jeste, D.V. Para-doxical trend for improvement in mental health with aging: A community-based study of 1,546 adults aged 21–100 years. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, e1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greenfield, E.A.; Marks, N.F. Formal Volunteering as a Protective Factor for Older Adults’ Psychological Well-Being. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2004, 59, S258–S264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S.; Underwood, L.G.; Gottlieb, B.H. Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L.; Tesch-Römer, C. Introduction to the Section: On the Manifestations and Consequences of Ageism. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism; Ayalon, L., Tesch-Römer, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Newbrough, J.R.; Chavis, D.M. Psychological sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, A.; Priel, B. Personality Vulnerability, Low Social Support, and Maladaptive Cognitive Emotion Regulation Under Ongoing Exposure to Terrorist Attacks. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 166–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, A.; Fristedt, S.; Boström, M.; Björklund, A.; Wagman, P. Occupational challenges and adaptations of vulnerable EU citizens from Romania begging in Sweden. J. Occup. Sci. 2018, 26, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S. Community and ageing: Maintaining Quality of Life in Housing with Care Settings; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J.M.; Nieboer, A.P. Relationships between frailty, neighborhood security, social cohesion and sense of belonging among community-dwelling older people. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2012, 13, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.B. How Many Subjects Does It Take to Do A Regression Analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1991, 26, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fedell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, J.; Mander, A. A review and re-interpretation of a group-sequential approach to sample size re-estimation in two-stage trials. Pharm. Stat. 2014, 13, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- American Counseling Association. ACA Code of Ethics. 2014. Available online: https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/2014-code-of-ethics-finaladdress.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Fraboni, M.; Saltstone, R.; Hughes, S. The Fraboni Scale of Ageism (FSA): An Attempt at a More Precise Measure of Ageism. Can. J. Aging/Rev. Can. Vieil. 1990, 9, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rababa, M.; Hammouri, A.M.; Hweidi, I.M.; Ellis, J.L. Association of nurses’ level of knowledge and attitudes to ageism toward older adults: Cross-sectional study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palgi, Y.; Grossman, E.S.; Hoffman, Y.S.; Pitcho-Prelorentzos, S.; David, U.Y.; Ben-Ezra, M. When the human spirit helps? The moderating role of somatization on the association between Olympic game viewing and the will-to-live. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 257, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanbar, L.; Kaniasty, K.; Ben-Tzur, N. Engagement in community activities and trust in local leaders as concomitants of psychological distress among Israeli civilians exposed to prolonged rocket attacks. Anxiety Stress Coping 2018, 31, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanic, D.; Bradburn, N.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1970, 35, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Persinal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buckner, J.C. The development of an instrument to measure neighborhood cohesion. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1988, 16, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Hsu, P.-H.; Hsu, S.-Y. Assessing the application of the neighborhood cohesion instrument to community research in East Asia. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 39, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bodner, E.; Cohen-Fridel, S.; Yaretzky, A. Sheltered housing or community dwelling: Quality of life and ageism among elderly people. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, C.; Goodwin, E.J.; Ferrari, J.R. Older Adult Stereotypes Among Care Providers in Residential Care Facilities: Examining the Relationship between Contact, Education, and Ageism. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2007, 33, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltes, P.B.; Smith, J. New Frontiers in the Future of Aging: From Successful Aging of the Young Old to the Dilemmas of the Fourth Age. Gerontology 2003, 49, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaster, P.B. A framework for polyvictimization in later life. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2017, 29, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, K.E.; Allen, P.D.; Denver, J.Y.; Holland, K.R. Contributions of Social Desirability to Self-Reported Ageism. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2013, 34, 712–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalon, L.; Dolberg, P.; Mikulionienė, S.; Perek-Białas, J.; Rapolienė, G.; Stypinska, J.; Willińska, M.; de la Fuente-Núñez, V. A systematic review of existing ageism scales. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 54, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avidor, S.; Ayalon, L.; Palgi, Y.; Bodner, E. Longitudinal associations between perceived age discrimination and subjective well-being: Variations by age and subjective life expectancy. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 21, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Hackett, R.A.; Steptoe, A. Associations between age discrimination and health and wellbeing: Cross-sectional and prospective analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e200–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damianakis, T.; Wilson, K.; Marziali, E. Family caregiver support groups: Spiritual reflections’ impact on stress management. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 22, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.R.; Cohen, H.L. Social Work with Older Adults and Their Families: Changing Practice Paradigms. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2005, 86, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, G.J.; Wallace, S. The Cost of Caring: Economic Vulnerability, Serious Emotional Distress, and Poor Health Behaviors Among Paid and Unpaid Family and Friend Caregivers. Res. Aging 2017, 40, 791–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Corrêa, L.; Caparrol, A.J.D.S.; dos Santos, P.T.A.; Brugnera, L.M.; Gratão, A.C.M. Sociodemographic and health characteristics of formal and informal caregivers of elderly people with Alzheimer’s Disease. Esc. Anna Nery 2019, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | ---- | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | −0.19 ** | ---- | |||||||||

| 3. Years of education | 0.43 *** | −0.02 | ---- | ||||||||

| 4. Income | 0.47 *** | −0.19 ** | 0.40 *** | ---- | |||||||

| 5. Marital status | −0.24 *** | −0.05 | −0.32 *** | −0.25 *** | ---- | ||||||

| 6. Somatization | −0.27 *** | 0.31 *** | −0.22 ** | −0.30 *** | 0.26 *** | ---- | |||||

| 7. Post-traumatic distress | −0.12 * | 0.07 | −0.25 *** | −0.09 | 0.33 *** | 0.52 *** | ---- | ||||

| 8. Psychological well-being | 0.11 | 0.19 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.17 * | −0.33 *** | −0.35 *** | −0.53 *** | ---- | |||

| 9. Social support | 0.04 | 0.13 * | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.42 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.51 *** | 0.61 *** | ---- | ||

| 10. Community belonging | 0.23 ** | 0.10 | 0.22 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.39 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.36 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.55 *** | ---- | |

| 11. Ageism | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.20 ** | −0.15 * | 0.15 * | 0.22 ** | 0.30 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.15 * | ---- |

| Mean | 36.21 | ---- | 15.98 | ---- | ---- | 19.73 | 36.92 | 3.01 | 4.12 | 3.30 | 1.78 |

| Standard Deviation | 11.42 | ---- | 3.05 | ---- | ---- | 4.45 | 16.23 | 0.48 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.35 |

| Variables | Coefficients | R-Square | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | B | SE | CI | VIF | |||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| Step 1: Background variables | R2 = 0.073 * | ||||||

| Age | 0.180 * | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 1.44 | |

| Gender | 0.042 | 0.034 | 0.058 | −0.080 | 0.148 | 1.07 | |

| Years of education | −0.189 * | −0.021 | 0.009 | −0.040 | −0.003 | 1.38 | |

| Income | −0.126 | −0.049 | 0.032 | −0.111 | 0.014 | 1.41 | |

| Marital status | 00.100 | 0.078 | 0.058 | −0.036 | 0.192 | 1.15 | |

| Step 2: Physical/psychological variables | R2 = 0.148 ***, ΔR2 = 0.075 | ||||||

| Somatization | 0.052 | 0.004 | 0.007 | −0.009 | 0.018 | 1.70 | |

| Post-traumatic distress | 0.168 * | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 1.82 | |

| Psychological well-being | −0.142 * | −0.102 | 0.061 | −0.223 | 0.019 | 1.64 | |

| Step 3: Social variables | R2 = 0.161 ***, ΔR2 = 0.014 | ||||||

| Social support | −0.170 * | −0.070 | 0.040 | −0.148 | 0.009 | 2.14 | |

| Community belonging | 0.057 | 0.020 | 0.030 | −0.040 | 0.080 | 1.68 | |

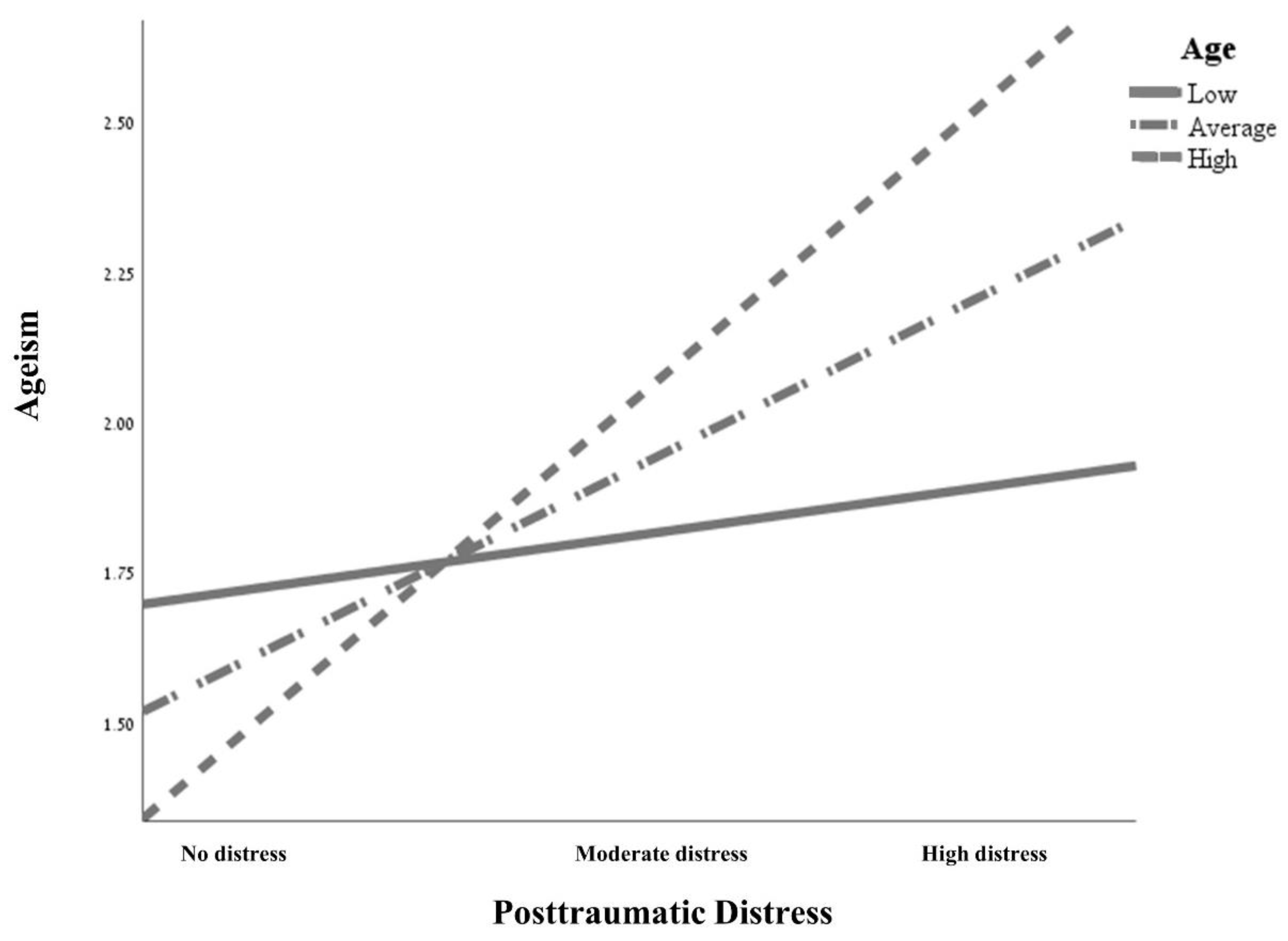

| Step 4: Interactions of age with independent variables | R2 = 0.225 ***, ΔR2 = 0.064 | ||||||

| Age X Post-traumatic distress | 0.277 *** | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | --- | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zanbar, L.; Lev, S.; Faran, Y. Can Physical, Psychological, and Social Vulnerabilities Predict Ageism? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010171

Zanbar L, Lev S, Faran Y. Can Physical, Psychological, and Social Vulnerabilities Predict Ageism? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010171

Chicago/Turabian StyleZanbar, Lea, Sagit Lev, and Yifat Faran. 2023. "Can Physical, Psychological, and Social Vulnerabilities Predict Ageism?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010171