Student Stress and Online Shopping Addiction Tendency among College Students in Guangdong Province, China: The Mediating Effect of the Social Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. OSAT and Student Stress

1.2. Social Support as a Mediator

1.3. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. College Student Online Shopping Addiction Tendency (OSAT) Scale

2.3.2. College Student Stress Scale

2.3.3. Social Support Scale

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Gender Difference

3.2. Analysis of the Difference in Levels of Stress

3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.4. Mediation Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, J. An Empirical Analysis of Psychological Factors Based on EEG Characteristics of Online Shopping Addiction in E-Commerce. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2021, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, J.; Bryan Lee, S. The interplay of Internet addiction and compulsive shopping behaviors. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2016, 44, 1901–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Yang, X. The effect of self-identity on online-shopping addiction in undergraduates: Taking Guangdong province as an example. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Seminar on Education Research and Social Science (ISERSS 2020), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 28 December 2020; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Forney, J.C.; Park, E.J. Browsing perspectives for impulse buying behavior of college students. TAFCS Res. J. 2009, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, Y.; Kutlu, M. Relationships among Internet addiction, academic motivation, academic procrastination and school attachment in adolescents. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 10, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer, H.H.; Sherman, L.E.; Chein, J.M. Smartphones and Cognition: A Review of Research Exploring the Links between Mobile Technology Habits and Cognitive Functioning. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samaha, M.; Hawi, N.S. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Dhandayudham, A. Towards an understanding of Internet-based problem shopping behaviour: The concept of online shopping addiction and its proposed predictors. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paulus, F.W.; Ohmann, S.; Von Gontard, A.; Popow, C. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Rohmann, E.; Bierhoff, H.-W.; Schillack, H.; Margraf, J. The relationship between daily stress, social support and Facebook Addiction Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 276, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. Influential factors for online impulse buying in China: A model and its empirical analysis. Int. Manag. Rev. 2015, 11, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Tian, W.; Xin, T. The Development and Validation of the Online Shopping Addiction Scale. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koran, L.M.; Faber, R.J.; Aboujaoude, E.; Large, M.D.; Serpe, R.T. Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying behavior in the United States. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1806–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A.; Mitchell, J.E.; Crosby, R.D.; Gefeller, O.; Faber, R.J.; Martin, A.; Bleich, S.; Glaesmer, H.; Exner, C.; de Zwaan, M. Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying in Germany and its association with sociodemographic characteristics and depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 180, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, S.L.; Keck, P.E.; Pope, H.G.; Smith, J.M.; Strakowski, S.M. Compulsive buying: A report of 20 cases. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Black, D.W. Compulsive Buying Disorder: A Review of the Evidence. CNS Spectr. 2007, 12, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, S.C.; Roitzsch, J.C. The impact of minor stressful life events and social support on cravings: A study of inpatients receiving treatment for substance dependence. Addict. Behav. 2000, 25, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeders, N.E. The impact of stress on addiction. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003, 13, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, D.; Cohen, L.; Campbell, A. Is traumatic stress a vulnerability factor for women with substance use disorders? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 25, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, S.; Sikora, P.; Grunberg, L.; Greenberg, E. Work stress and alcohol use: Examining the tension-reduction model as a function of worker’s parent’s alcohol use. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 3114–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leung, L. Stressful Life Events, Motives for Internet Use, and Social Support Among Digital Kids. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. A Survey on the Generalized Problematic Internet Use in Chinese College Students and its Relations to Stressful Life Events and Coping Style. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2008, 7, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Zhen, S.; Wang, Y. Stressful life events and problematic Internet use by adolescent females and males: A mediated moderation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, J.G.; Lacy, M.G.; Dengah, H.F.; Eisenhauer, S.; Batchelder, G.; Cookson, R.J. A vacation from your mind: Problematic online gaming is a stress response. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-T.; Wang, H.-Z.; Fonseca, W.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Rost, D.H.; Gaskin, J.; Wang, J.-L. The relationship between academic stress and adolescents’ problematic smartphone usage. Addict. Res. Theory 2018, 27, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velezmoro, R.; Lacefield, K.; Roberti, J.W. Perceived stress, sensation seeking, and college students’ abuse of the Internet. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1526–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, C.A.; McWey, L.M.; Howard, S.N.; Olmstead, S.B. College student stress: The influence of interpersonal relationships on sense of coherence. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2007, 23, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lin, C.-D.; Bray, M.A.; Kehle, T.J. The measurement of stressful events in Chinese college students. Psychol. Sch. 2005, 42, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Joshi, M.; Thomas, T.A. Excessive shopping on the internet: Recent trends in compulsive buying-shopping disorder. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2022, 44, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.E.; Syme, S.I. Social Support and Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, B.H.; Bergen, A.E. Social support concepts and measures. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caplan, G. The family as a support system. Support Syst. Mutual Help. Multidiscip. Explor. 1976, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, S. Social Support as a Moderator of Life Stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.S. Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley Ser. Occup. Stress 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Higgins, E.T. (Eds.) Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harandi, T.F.; Taghinasab, M.M.; Nayeri, T.D. The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5212–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, J.H.; Chen, M.C.; Yang, C.Y.; Chung, T.Y.; Lee, Y.A. Personality traits, interpersonal relationships, online social support, and Facebook addiction. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengqiang, G.; Jie, X.; Yueqiang, R.; Lei, H. The Relationship Between Internet Addiction and Aggression: Multiple Mediating Effects of Life Events and Social Support. J. Psychol. Res. 2016, 6, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Huang, N.; Fu, M.; Ma, S.; Chen, M.; Wang, X.; Feng, X.L.; Zhang, B. Social support as a mediator between internet addiction and quality of life among Chinese high school students. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 129, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, C. Self-control predicts attentional bias assessed by online shopping-related Stroop in high online shopping addiction tendency college students. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 75, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Zhao, J.; You, X. Self-Esteem as Mediator and Moderator of the Relationship Between Social Support and Subjective Well-Being Among Chinese University Students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 112, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J.E.; Potenza, M.N.; Krishnan-Sarin, S.; Cavallo, D.A.; Desai, R.A. Shopping problems among high school students. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spitze, G. The division of task responsibility in US households: Longitudinal adjustments to change. Soc. Forces 1986, 64, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.-S.; Seo, B.-K. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: Prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychol. Open 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunuc, S.; Dogan, A. The relationships between Turkish adolescents’ Internet addiction, their perceived social support and family activities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2197–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Bi, L.; Qian, Z.; Lu, S.; Feng, F.; Hu, C.; et al. Prevalence of Internet addiction and its association with social support and other related factors among adolescents in China. J. Adolesc. 2016, 52, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.S. Internet addiction: A new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 48, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yee, N. Motivations for Play in Online Games. Cyber Psychology Behav. 2006, 9, 772–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung CM, K.; Chan GW, W.; Limayem, M. A critical review of online consumer behavior: Empirical research. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. (JECO) 2005, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tavolacci, M.P.; Ladner, J.; Grigioni, S.; Richard, L.; Villet, H.; Dechelotte, P. Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: A cross-sectional study among university students in France 2009–2011. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Kong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Mei, S. The influence of alexithymia on mobile phone addiction: The role of depression, anxiety and stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Lindquist, R. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness in Korean nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, J.S.; Umberson, D.; Landis, K.R. Structures and processes of social support. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 1988, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, C.P.H.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social support: A conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, T. Assessing the Academic, Personal and Social Experiences of Pre-College Students. J. Coll. Admiss. 2005, 186, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Poyrazli, S.; Kavanaugh, P.R.; Baker, A.; Al-Timimi, N. Social Support and Demographic Correlates of Acculturative Stress in International Students. J. Coll. Couns. 2004, 7, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Koeske, G.F.; Sales, E. Social support buffering of acculturative stress: A study of mental health symptoms among Korean international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2004, 28, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mei, J.R. Development of stress scale for college student. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 8, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, A.; Brand, M.; Claes, L.; Demetrovics, Z.; de Zwaan, M.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Frost, R.O.; Jimenez-Murcia, S.; Lejoyeux, M.; Steins-Loeber, S.; et al. Buying-shopping disorder—Is there enough evidence to support its inclusion in ICD-11? CNS Spectr. 2019, 24, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchiraju, S.; Sadachar, A.; Ridgway, J.L. The Compulsive Online Shopping Scale (COSS): Development and Validation Using Panel Data. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 15, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Student Stress | OSAT | Social Support | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 65.32 ± 17.56 | 51.13 ± 15.21 | 14.55 ± 2.85 |

| Female | 64.48 ± 16.54 | 50.69 ± 15.11 | 14.63 ± 2.96 | |

| t | 0.497 | 0.292 | −0.271 |

| Social Support | OSAT | |

|---|---|---|

| The high-stress group | 13.52 ± 2.77 | 52.27 ± 13.88 |

| The low-stress group | 16.08 ± 2.34 | 45.40 ± 3.81 |

| t | 7.579 *** | −5.01 *** |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Personal Hassle | 29.84 | 10.42 | 0.924 | |||||

| 2 | Academic Hassle | 26.81 | 9.62 | 0.923 *** | 0.923 | ||||

| 3 | Negative Life Events | 11.49 | 4.03 | 0.902 *** | 0.890 *** | 0.821 | |||

| 4 | Total Stress | 64.95 | 17.11 | 0.738 *** | 0.737 *** | 0.690 *** | 0.967 | ||

| 5 | OSAT | 50.94 | 15.15 | 0.166 *** | 0.173 *** | 0.173 *** | 0.353 *** | 0.958 | |

| 6 | Social Support | 14.58 | 2.89 | −0.216 *** | −0.203 *** | −0.171 *** | −0.368 *** | −0.351 *** | 0.704 |

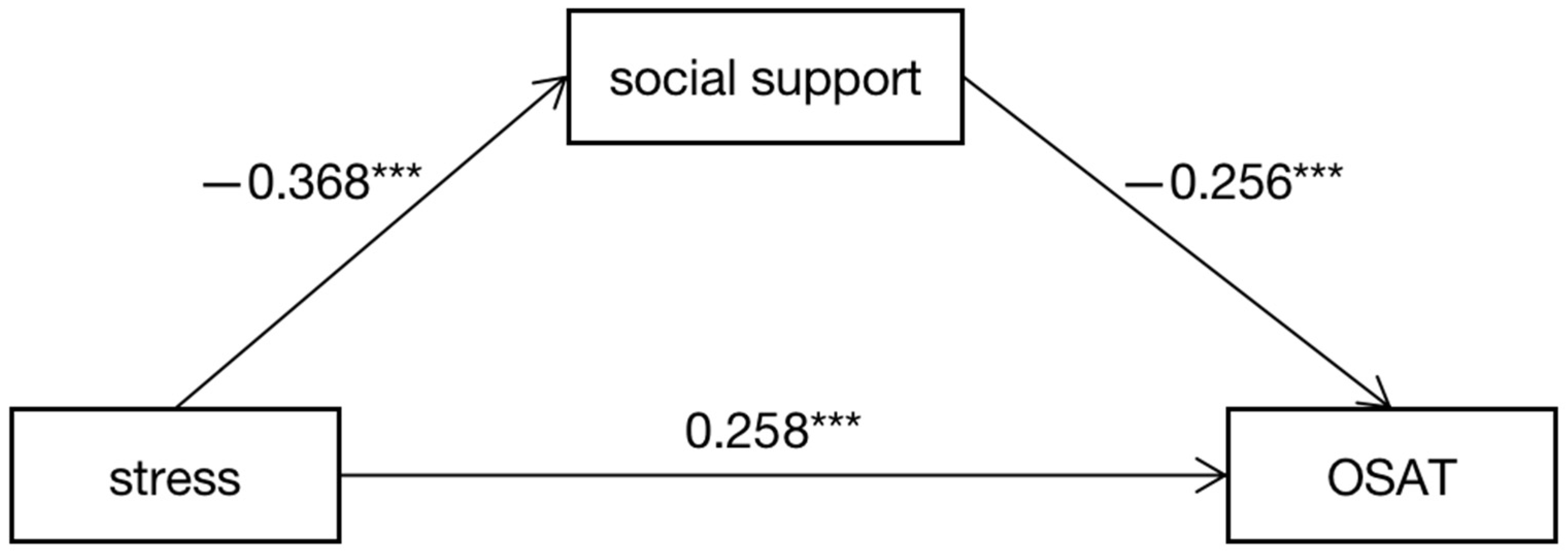

| Effect | β | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Direct effects | ||||

| Total Stress→Social Support | −0.368 *** | 0.034 | −0.435 | −0.302 |

| Total Stress→OSAT | 0.258 *** | 0.063 | 0.129 | 0.380 |

| Social Support→OSAT | −0.256 *** | 0.030 | −0.317 | −0.200 |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Total Stress→Social Support→OSAT | 0.094 *** | 0.014 | 0.062 | 0.118 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Ma, X.; Fang, J.; Liang, G.; Lin, R.; Liao, W.; Yang, X. Student Stress and Online Shopping Addiction Tendency among College Students in Guangdong Province, China: The Mediating Effect of the Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010176

Li H, Ma X, Fang J, Liang G, Lin R, Liao W, Yang X. Student Stress and Online Shopping Addiction Tendency among College Students in Guangdong Province, China: The Mediating Effect of the Social Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Huimin, Xinyue Ma, Jie Fang, Getian Liang, Rongsheng Lin, Weiyan Liao, and Xuesong Yang. 2023. "Student Stress and Online Shopping Addiction Tendency among College Students in Guangdong Province, China: The Mediating Effect of the Social Support" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010176