Indigenous Knowledge: Revitalizing Everlasting Relationships between Alaska Natives and Sled Dogs to Promote Holistic Wellbeing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. A Story of Holistic Connection

1.2. George Attla Jr.’s Legacy

1.3. Indigenous Worldviews

1.4. Indigenous Place-Based Learning and Wellbeing

1.5. Digital Storytelling and Cultural Connection

1.6. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Partnership

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Youth Photovoice and Digital Storytelling Sessions

2.4.2. Adult Focus Groups

2.5. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Dog Relationships

3.1.1. Cultural Upbringing Sparks Interest in Sled Dogs

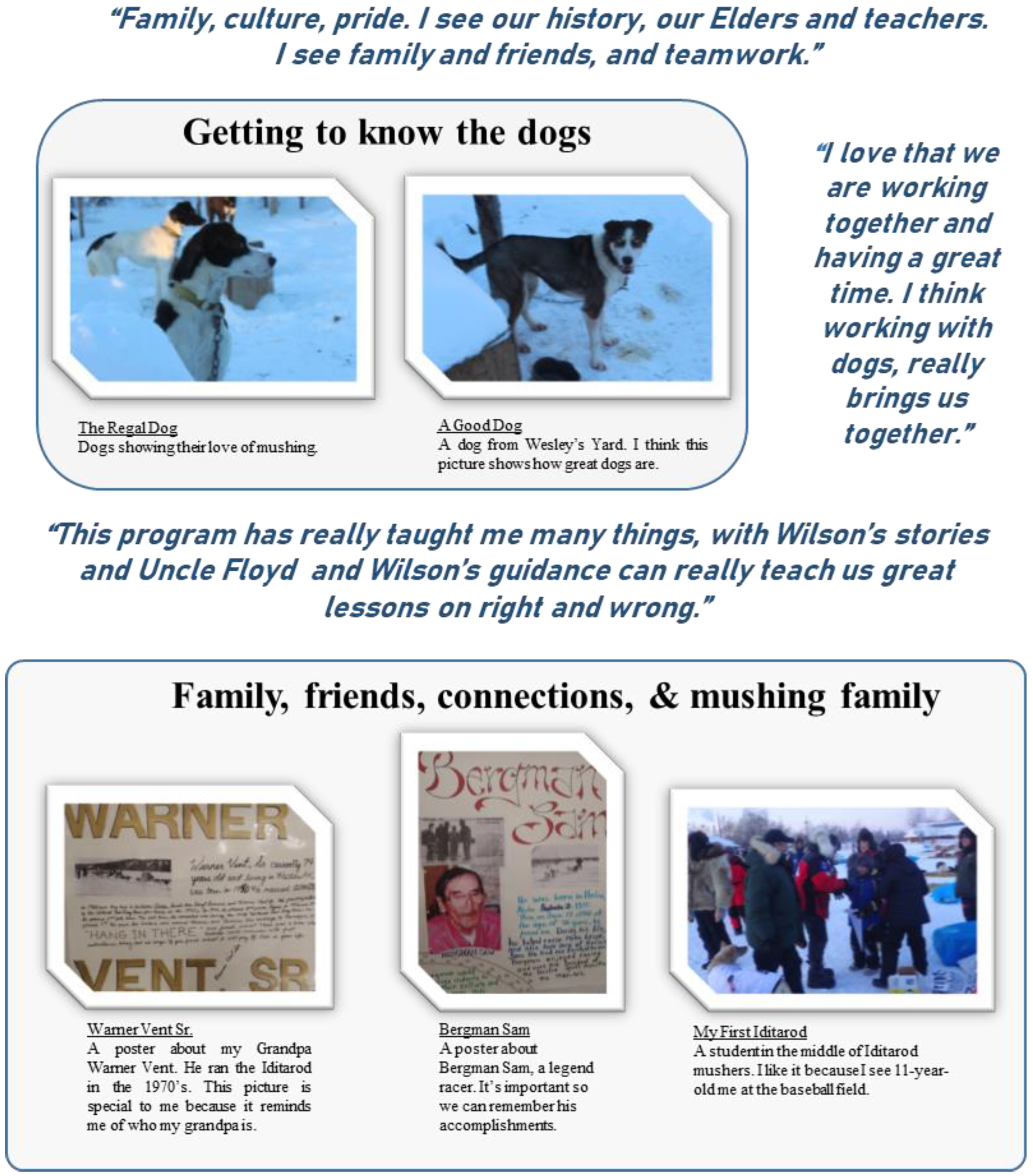

My grandpa Warner Vent was an Iditarod musher; in the early 1970s, he won second place twice. He is the one who has really inspired me to get involved with dogs and this program.

So, my late grandpa Cue Bifelt won the Open North American Championship sled dog race, which is one of the biggest sprint dog races in the world. The Frank Attla Program taught me how to work with dogs and learned some history from where I come from.

3.1.2. Youths View Sled Dogs as Welcoming and Capable of Educating

Personally, both my boys have been in the program, and my boys are really quiet, and they’re really shy. And T, I was even shocked that T did a video. He’s never done anything like that before. And so, it does make a huge difference on their self-esteem. H, when he was in high school, he was shy, and he wouldn’t open up to nobody. But when he went in that dog yard, he was all aboard, you know. And it came, it brought him out of his shell. So, it does make a big difference all the way around.

I finally raced in a four-dog race at the carnival a couple years ago. I was very excited I remember thinking that I was certainly going to fall over or tip. But it turns out I didn’t, and running with the dogs was very peaceful.

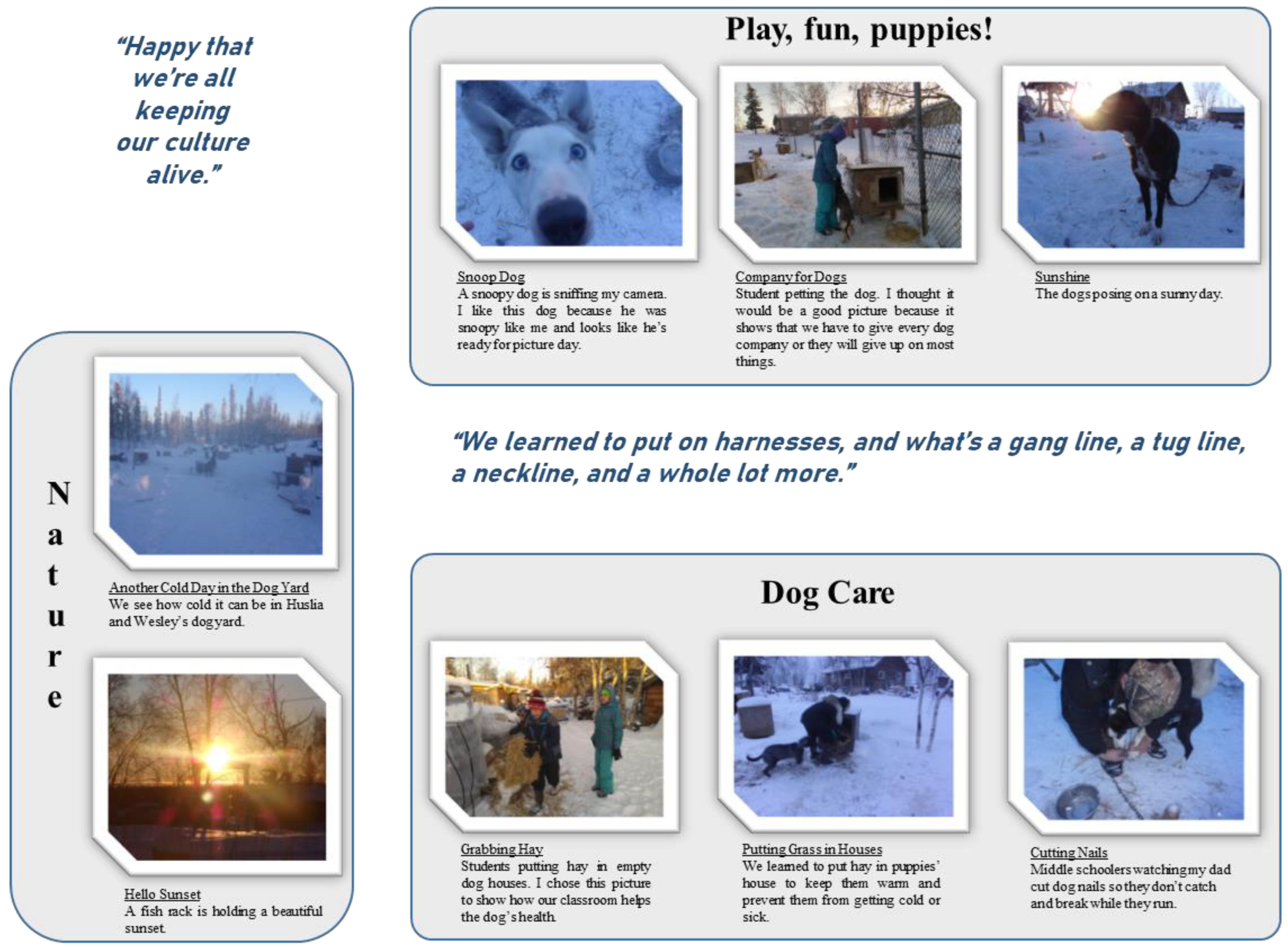

3.1.3. Lessons in Caring for Sled Dogs and in Kennel Maintenance

There is always work that needs to be done, cleaning poop around the dogs and puppies, chopping wood for the dog pot, cooking the dog pot, feeding and watering the dogs, and a whole lot more to do. I’m one of the few lucky kids that has a parent or grandparent that has a dog yard. It’s a lot of work, but that is also a good thing, it helps to teach you what hard work is, and also helps to have a better work ethic. It definitely fills the day, taking wet, peed on grass out of houses and putting fresh, dry grass in their houses so they can stay warm and healthy. Running them, cutting their nails, checking their arms and legs to see if they’re hurt or sore. Dry off harnesses and gang lines, making sure you got everything, hooks, harnesses, ganglines and necklines. You also have to run the dogs daily, keep them healthy and in shape. Which also reminds me to stay healthy and in shape myself. If dogs don’t run, they start getting depressed, and start getting sick, and start losing weight.

Family, culture, pride. I see our history, our elders and teachers. I see family and friends, and teamwork.

Getting ready to feed dogs. All working together. Happy people.

I feel happy that dog yards still make people happy.

We are socializing with the puppies, having fun. Learning how to coach puppies. I love that we’re working together to help these puppies and teach them how to race and listen good.

3.1.4. Sled Dogs Spark Intergenerational Relationships

Kathy Turco and George Attla always liked working with the community… They always liked to help with my little brothers after my dad gave away his dogs. They always let my brother come over to visit their dogs, even when my brothers missed their puppies. I remember Kathy letting us play with their puppies. They even let my brothers feed their dogs and I always saw them come home with big smiles saying that they had fed their dogs.

3.2. Environment

3.2.1. Huslia Attachment and How the Youths Define Huslia

Hi, my name is Jordan Vent welcome to a place that is surrounded by forests and rivers, called Huslia Alaska.

Hi, my name is Jeremiah Henry. I’m from Huslia, Alaska, a place that is rich in dog mushing.

JesCynthia David se’ooze, dehoon Denaakk’e helde Hedo’ketlno seeznee. Ts’aateydenaadekk’ohn Dehn hut’aanh eslaanh. My name is JesCynthia David while in Denaakk’e they call me Hedo’ketlno, and I am of the Huslia people.

3.2.2. Connection to Land

When I go racing I always think I’m gonna tip or crash into a tree until I realize I can really trust the dogs. Mushing also brings me into nature and I watch the birds and look at the trees and other stuff.

3.2.3. Things Learned at Different Dog Yards

We go to three different dog yards. The dog yards we go to are Wesley, Wilson, and Floyd’s dog yards. Each dog yard is different from the other. At Wesley’s dog yard we go running with the dogs. At Wilson’s dog yard, he tells us stories, and then we go outside and clean up the dogs; sometimes we run the puppies. At Floyd’s dog yard, we play with the puppies and cut food for the dogs. We sometimes harness the dogs and let Floyd run them while we wait and play with the puppies.

I’ve learned everything from talking to older people when I was younger how to race dogs. I’ve called on many people, asked them questions. George, there are other people, you know, they’re Cue Bifelt, Lester Erhart, Freddy Jordan, all the people I have known throughout the years. And I’ve learned from other people how to race dogs. Not saying I was the best dog musher in the world, but it made me better. I was able to communicate with older people because we had a common interest.

3.2.4. Sled Dogs Bring Communities Together

Students that go through the program, they start learning about dogs, and it sparks the interest for them, the children. So, when the children have an interest in something, you know, the parents tend to want to support their interest or what not… But when you start seeing your children have an interest in it, you tend, as a community member, the community, to get more involved.

3.2.5. A-CHILL Good for Huslia

The Frank Attla Youth and Sled Dog Care—Mushing Program means a lot to me. It is a program where the students can participate and have fun with dogs, dog care, and mushing. A lot of fun activities and projects. This program means a lot to Huslia.

I think just by using dogs, as an example, we could do that, we could show them that, it’s scary to go to Fairbanks or Anchorage and race, that’s not easy. Or Iditarod. But when we do things like that, we grow from pretty strongly because of it. That is what I want our kids to see, and they’ll do the same thing, you know. Apples don’t fall too far from the tree, but we do is for our kids is going to do. And if we hold back, they are going to hold back too. So we have got to challenge ourselves to push that envelope, and that is what we have to do if we want our kids, and our grandkids, the future generations to be successful.

3.2.6. A-CHILL Promotes Unity between the School and Community

When it [FAYSDP] first started, I was a senior in high school, and I remember before that like in middle school and everything there was a high turnover rate, teachers are in and out. So, therefore, like students don’t really respect the teachers as much, like they’re probably going to leave anyway. We had a teacher leave after 1 week before. So, we don’t have, we don’t really respect them. And they’re from somewhere far away, they don’t really know how to connect with the students. So, after the program started, I could kind of notice that once the teacher started showing interest in our culture, and they had a vehicle to connect the school content with the students; then, the students were able to respect the teachers more, too. And I remember as a student seeing my classmates respect Ms. B more, or something like that, because we had that relationship in class.

3.3. Human Relationships

3.3.1. Intergenerational Relationships

I watch other people race to and this year race I came in first place, I made sure to thank my grandpa since I used his dogs. It felt great to hear that I got first when I crossed the finish line.

I work with youth, and a lot of them are shy. They don’t, wouldn’t naturally just open up to people, or if you’re walking by them, they’ll kind of just, the shy ones will just look down, no eye contact, and they’ll just walk by as fast as they can. But I feel like especially the shy ones they get good relationships with the dogs first. And then like J was talking about, then they’re, pretty soon they’re working together [with their peers], and doing these things that they don’t even realize they’re doing. And talking to the mushers, and they’re all asking questions, and just like what B was saying they have something in common to talk about. And so I think it, for the community it created a, you know, where there was a gap probably before it brought them closer together.

Dogs helped me learn more about my culture, with respect and how we used to rely on them. We used them for travelling, for hunting, trapping, bringing medicine and mail from village to village, and just to have them there with you.

My favorite part of being here is the dog program, I like to get out and help out with dog yards. It is a great opportunity for me to be able to learn how our elders lived years ago and how to take care of and raise dogs.

When we are at a Culture Camp and they were doing gang lines and stuff, and the kids were sitting here doing these measurements and stuff, and they’re just, they’re doing it by watching the Elder teaching them. And they don’t even realize it, but they learn a lot, and they learn how to do the measurements and different ways of measuring. And the skills of how to problem solve and everything, they might not mention it, but if you actually watch them do it, I mean I didn’t even know. When you are watching them do that, you can see it. That is one of the things that I got out of the videos and stuff, you could see the change in them.

3.3.2. Positive Feelings toward Themselves

Overall, it’s a great thing having a dog yard. It will help my future in many different ways, it teaches me what determination is, it will help me have a better attitude towards work and have a good work ethic.

I think when Uncle George first started that, those kids went a long way. He instilled in them that they have to love and respect each other. They don’t realize it, but when they are working, they are working in teamwork, and they do a lot of that. And he told them they would go a long way if they respect people and love them.

3.4. Inseparable Spheres

I especially love how we are still doing this, sure we now have snow-gos and boats, and cell phone service, but we still have races, KRC’s [Koyukuk River Championship—a prominent sprint sled dog race happening each year in alternating Koyukuk River communities, Huslia, Hughes, and Allakaket], potlatches, and cover dishes, things that keep our culture alive.

Most of us grew up racing throughout the years. The sound the bottom of the sled makes when we run, that makes me content. At age 13, some of us know how to take care of dogs, run them, and accompany them. Our elders and locals teach us, provide us, and most of all they are our companions.

I love running dogs and racing in competitions. During competitions, there is often a ton on your mind, and it is easy to feel anxious. Even with all these feeling, I love how dogs have almost a magical power to give you a calming peace. While running dogs, I find clarity; it’s a period of time without noise and voices.

I notice a lot of the kids here in this community are resilient. They’re able to understand that… there’s a process, and understand that process, and taking it back with them allows them to be a little bit more versatile when they go on and be independent. But just understand that there’s a process, and that goes with the collecting the fish, the food, and how to treat your dogs. I was just saying that I notice that it allows them to be really resilient, they’re able to take the resources that they have, and they’re able to excel from it…It allows them to give them that … edge… they’re really able and understand that it’s a lot, also not along with just that resiliency but unity.

It comes to two things… It’s a sense of purpose, and I heard it in here before, and self-pride. And if you have those things, you know, if you have a sense purpose. I mean within this community…And when you have these things…it builds, other things build around it, and maybe you’re less likely to hurt yourself or what not if you feel like you belong. And that comes with self-pride and sense of purpose.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretations and Connections

Being in and with the environment the whole year round, students can experience the vicissitudes of seasons, flora, fauna, sunlight, freezing, thawing, wind, weather permutations, gaining intimate knowledge about place using their five senses and intuition to learn about themselves and the world around them[79] (pp. 14–15)

4.2. Strengths, Limitations, and Implications for the Future

5. Conclusions and First Author’s Reflections

Janessa Newman

Ultimately I think dog mushing has done something for our people that… I don’t think people really recognize it. What I mean by that is look back in our history, and we see a lot of champions come from Koyukuk River, and the challenges, and what it took for them to take that challenge, to push the envelope, get outside of their comfort zone. I think that is really important. Especially… in light of how our lives are today… It’s just a new diameter… But it is really important for our kids to go on and achieve goals and education so they can use that to set themselves up for their future, create a foundation for themselves… They [Elders] had the will and the drive…But I think that’s one thing I never see discussed in the Frank Attla Youth Program or Huslia, or any other, what it takes for an individual to get out of their comfort zone, and go out into the world somewhere and try to achieve a goal. I think that is really… we know that is important… I look at our education program and there is nothing wrong with our people living in our villages, there is nothing wrong with that at all. The only thing about it is it is difficult to make a living; so, our young people have to have a means of some kind of tool that they could support themselves… In the last 15 years, a lot of our students leave our schools, and this school included. And they go and they run into difficult times in trying to get their college degree or whatever. They eventually come home, which is fine, there is nothing wrong with that. But it is my hope and my dream to get a higher percentage of our school (students) just continue on, and tough it out, and get their degrees, so they can use that as a tool to support themselves, but ultimately, to make society a better place than what they find. For them to come back and help in our community, where help is really needed. That is what I think this was designed to do and I hope that’s how it’s interpreted someday… But I don’t think I have heard enough of how these students are that learn how to set goals for themselves and stay on the task, stay the course and achieve their goals. So ultimately, they have turned around they’d be able to use that to better themselves, better their lives. To be able to support themselves, that is the key right there. That is what I really want to see for our young people because man, like I said earlier, the dynamics are changing. Our old way of life of living on the land, it is virtually nonexistent now… So that is why it is really important for our young people to get a degree in college, or military service, or GTE, or some way to put tools in their toolbox where they can use it to make a living. I think, I know that is part of why George started A-CHILL. He saw that, and that is what he told me.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Freedman, L. Spirit of the Wind: The Story of George Attla, Alaska’s Legendary Sled Dog Sprint Champ; Epicenter Press: Kenmore, WA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, R. Spirit of the Wind; Doyon Ltd. and Gana A’Yoo Ltd.: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Axley, C. ATTA; Independent Television Service; Vision Maker Media: San Francisco, CA, USA; Lincoln, NE, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, J. Toward a Philosophical Understanding of TEK and Ecofeminism. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability; Nelson, M.K., Shilling, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiste, M.; Henderson, J. Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge; Purich Publishing Ltd.: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2000; pp. 171–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence; Clear Light Publishers: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, S. Indigenous sustainability: Language, community, wholeness, and solidarity. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability; Nelson, M.K., Shilling, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kawagley, A.O. A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit; Institute of Education Sciences; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods; Fernwood Publishing: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, D. Coming full circle: Indigenous knowledge, environment, and our future. Am. Indian Q. 2004, 28, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, G. Language and Art in the Navajo Universe; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Little Bear, L. Traditional knowledge and humanities: A perspective by a Blackfoot. J. Chin. Philos. 2012, 4, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayunerak, P.; Alstrom, D.; Moses, C.; Charlie, J.; Rasmus, S. Yup’ik culture and context in southwest Alaska: Community member perspectives of tradition, social change, and prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 54, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnhardt, R. Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska Native ways of knowing. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 2005, 36, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M. Alaska Native Political Leadership and Higher Education: One University, Two Universes; Rowman Altamira: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, R. Race in higher education. In The Racial Crisis in American Higher Education: Continuing Challenges for the Twenty-first Century; University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review: Little Rock, AR, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.M.; Davidson-Hunt, I. Agency and resilience: Teachings of Pikangikum First Nation elders, northwestern Ontario. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merculieff, L.; Roderick, L. Stop Talking. Indigenous Ways of Teaching and Learning and Difficult Dialogues in Higher Education; University of Laska Anchorage: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, J.; Newman, J.; Bifelt, J.; Brooks, C.; Rivkin, I. Role of social, cultural and symbolic capital for youth and community wellbeing in a rural Alaska Native community. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 137, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, J.K.; Richmond, C.A.M. “That land means everything to us as Anishinaabe...”: Environmental dispossession and resilience on the North Shore of Lake Superior. Health Place 2014, 29, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, C.A.M.; Ross, N.A. The determinants of First Nation and Inuit health: A critical population health approach. Health Place 2009, 15, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carothers, C.; Black, J.; Langdon, S.J.; Donkersloot, R.; Ringer, D.; Coleman, J.; Gavenus, E.R.; Justin, W.; Williams, M.; Christiansen, F.; et al. Indigenous peoples and salmon stewardship: A critical relationship. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, M.J.; Lalonde, C.E. Cultural Continuity as a Hedge against Suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcult. Psychiatry 1998, 35, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.C. Participation in Governance and Well-Being in the Yukon Flats; Washington University in St. Louis: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, M.C.; Skan, J.; David, E.J.R.; Lopez, E.D.S.; Prochaska, J.J. Indigenizing Quality of Life: The Goodness of Life for Every Alaska Native Research Study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1123–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivkin, I.; Lopez, E.D.S.; Trimble, J.E.; Johnson, S.; Orr, E.; Quaintance, T. Cultural values, coping, and hope in Yup’ik communities facing rapid cultural change. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.K.B.; Lopez, E.D.S.; Mekiana, D.; Ctibor, A.; Church, C. “What makes life good?” Developing a culturally grounded quality of life measure for Alaska Native college students. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmus, S.M.; Charles, B.; Mohatt, G.V. Creating Qungasvik (a Yup’ik intervention “toolbox”): Case examples from a community-developed and culturally-driven intervention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 54, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, K.; Walters, K.L.; Beltran, R.; Stroud, S.; Johnson-Jennings, M. “I’m stronger than I thought”: Native women reconnecting to body, health, and place. Health Place 2016, 40, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, M.; Kuhnley, R.; Lanier, A.; Dignan, M.; Revels, L.; Schoenberg, N.E.; Cueva, K. Promoting Culturally Respectful Cancer Education Through Digital Storytelling. Int. J. Indig. Health 2016, 11, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, I.; Black, J.; Lopez, E.; Filardi, E.; Salganek, M.; Newman, J.; Haire, J.; Nanook, M.; Philip, J.; Charlie, D.; et al. Integrating mentorship and digital storytelling to promote wellness for Alaska Native youth. J. Am. Indian Educ. 2020, 59, 169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, L. Intergenerational dialogue exchange and action: Introducing a community-based participatory approach to connect youth, adults and elders in an Alaskan Native. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2011, 10, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L.; Eglinton, K.; Gubrium, A. Using Digital Stories to Understand the Lives of Alaska Native Young People. Youth Soc. 2014, 46, 478–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.; Hessler, B. Digital Storytelling: Story Work for Urgent Times; Digital Diner Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, L.; Gubrium, A.; Griffin, M.; DiFulvio, G. Promoting positive youth development and highlighting reasons for living in Northwest Alaska through digital storytelling. Health Promot. Pract. 2013, 14, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, M.K.; Morgan, V.S.; Mitchell-Foster, K.; Parkes, M.W. Voices from the landscape: Storytelling as emergent counter-narratives and collective action from northern BC watersheds. Health Place 2018, 54, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littrell, M.K.; Okochi, C.; Gold, A.U.; Leckey, E.; Tayne, K.; Lynds, S.; Williams, V.; Wise, S. Exploring students’ engagement with place-based environmental challenges through filmmaking: A case study from the Lens on Climate Change program. J. Geosci. Educ. 2020, 68, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.; Bird-Naytowhow, K.; Pearl, T.; Hatala, A.R. “Just because they aren’t human doesn’t mean they aren’t alive”: The methodological potential of photovoice to examine human-nature relations as a source of resilience and health among urban Indigenous youth. Health Place 2020, 61, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.B.; Silva, L. Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, L.; Jernigan, K.; Mazzotti, J.; Baldwin, E.; Griffin, M.; Joule, L.; Garoutte, J.; CIPA Team. Lived challenges and getting through them: Alaska Native youth narratives as a way to understand resilience. Health Promot. Pract. 2014, 15, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trout, L.; Wexler, L.; Moses, J. Beyond two worlds: Identity narratives and the aspirational futures of Alaska Native youth. Transcult. Psychiatry 2018, 55, 800–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, L. Looking across three generations of Alaska Natives to explore how culture fosters indigenous resilience. Transcult. Psychiatry 2014, 51, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, A.; Sims, L.; Clarke, K.; Russo, F.A. Indigenous youth reconnect with cultural identity: The evaluation of a community- and school-based traditional music program. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USA. Census Bureau Census Reporter Profile Page for Huslia. Available online: http://censusreporter.org/profiles/16000US0234350-huslia-ak/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Alaska Department of Education and Early Development Jimmy Huntington School. Available online: https://education.alaska.gov/compass/ParentPortal/SchoolProfile?SchoolID=520040 (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Andersen, D.B. The Use of Dog Teams and the Use of Subsistence-Caught Fish for Feeding Sled Dogs in the Yukon River Drainage, Alaska; Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence: Juneau, AK, USA, 1992.

- Lopez, E.D.S.; Eng, E.; Robinson, N.; Wang, C. Photovoice as a community based participatory reasearch method. In Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health; Israel, B.A., Eng, E., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 326–348. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium, A.C.; Turner, K.C.N. Digital storytelling as an emergent method for social research and practice. In Handbook of Emergent Technologies in Social Research; Hess-Biber, S.N., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, C. Practical Facilitation: A Toolkit of Techniques; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- WeVideo. WeVideo Online Video Editor 2020; WeVideo: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turco, K. A-CHILL Web Site. What We Did. Available online: https://www.achill.life/what-we-did (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Turco, K. A-CHILL Web Site. What We Learned. Available online: https://www.achill.life/what-we-learned (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Philip, J.; Rivkin, I.; Newman, J.; Bifelt, J.; Brooks, C.; Stejskal, M. Center for Alaska Native Health Research, Stories and Images of Community Strength from a Youth Dog Mushing Program in Rural Alaska. Available online: https://canhr.uaf.edu/research/past-canhr-projects/faysdp/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Muhr, T.; Friese, S. User’s Manual for ATLAS. to 5.0; Scientific Software Development GmbH.: Munich, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Denakkanaaga Elders Conference Athabascan Cultural Values. Available online: http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/ancr/Values/athabascan.html (accessed on 19 September 2016).

- Schaefer-McDaniel, N.J. Conceptualizing social capital among young People: Towards a new theory. Child. Youth Environ. 2004, 14, 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, S.L. Quality and Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet, C.; André, N.; Gentet, J.-C.; Verschuur, A.; Michel, G.; Sotteau, F.; Martha, C.; Grélot, L. Pilot evaluation of physical and psychological effects of a physical trek programme including a dog sledding expedition in children and teenagers with cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2015, 9, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.K. Make prayers to the raven. A Koyukon View of the Northern Forest; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, R.; Robinson, J.T.; Hughes, A.R.; Tobias, P.V.; Clarke, R.; Partridge, T.C.; Partridge, T.C.; Maud, R.R.; Partridge, T.C.; Granger, D.E.; et al. Why Copy Others? Insights from the Social Learning Strategies Tournament. Science 2010, 328, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.A. Peer Relationships and Camps. Available online: https://www.acacamps.org/sites/default/files/downloads/Briefing-Paper-Peer-Relationships-Camps.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Gowing, A. Peer-peer relationships: A key factor in enhancing school connectedness and belonging. Educ. Child Psychol. 2019, 36, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Little, M.E. Learning the community’s curriculum: The linguistic, social, and cultural resources of American Indian and Alaska Native children. In American Indian and Alaska Native Children’s Mental Health: Development and Context; Sarche, M.C., Spicer, P., Farrell, P., Fitzgerald, H.E., Eds.; Praeger, ABC-Clio LLC: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gormley, W.T. The Critical Advantage: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in School; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Powney, J.; Lowden, K.; Hall, S. Young People’s Life-Skills and the Future; Scottish Council for Research in Education: Edinburgh, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise, T.; Howard-Pitney, B. The Zuni life skills development curriculum: Description and evaluation of a suicide prevention program. J. Couns. Psychol. 1995, 42, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little Bear, L. Jagged worldviews colliding. In Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision; Battiste, M., Ed.; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2000; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald, C.A.; Fullerton, L.; Green, D.; Hall, M.; Penaloza, L.J. The Association Between Positive Relationships with Adults and Suicide-Attempt Resilience in American Indian Youth in New Mexico. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2017, 24, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, C.B.; Reinschmidt, K.; Teufel-Shone, N.I.; Oré, C.E.; Henson, M.; Attakai, A. American Indian Elders’ resilience: Sources of strength for building a healthy future for youth. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L.; Moses, J.; Hopper, K.; Joule, L.; Garoutte, J.; LSC CIPA Team. Central role of relatedness in Alaska native youth resilience: Preliminary themes from one site of the Circumpolar Indigenous Pathways to Adulthood (CIPA) study. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 52, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, A.M.; Narvaez, D.; Kohn, R.; Bae, A. Indigenous Nature Connection: A 3-Week Intervention Increased Ecological Attachment. Ecopsychology 2020, 12, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Astell-Burt, T.; Barber, E.A.; Brymer, E.; Cox, D.T.C.; Dean, J.; Depledge, M.; Fuller, R.A.; Hartig, T.; Irvine, K.N.; et al. Nature-Based Interventions for Improving Health and Wellbeing: The Purpose, the People and the Outcomes. Sport 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The new psychology of success; Random House: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, E.; Quick, L.; Buchanan, D. Systemic threats to the growth mindset: Classroom experiences of agency among children designated as ‘lower-attaining’. Camb. J. Educ. 2021, 51, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, C.C.T.; Allen, J.; Henry, D.; Mohatt, G. V Multicultural Mastery Scale for Youth: Multidimensional assessment of culturally mediated coping strategies. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 24, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.M.; Usborne, E. When I know who “we” are, I can be “me”: The primary role of cultural identity clarity for psychological well-being. Transcult. Psychiatry 2010, 47, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usborne, E.; de la Sablonnière, R. Understanding My Culture Means Understanding Myself: The Function of Cultural Identity Clarity for Personal Identity Clarity and Personal Psychological Well-Being. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2014, 44, 436–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogashoa, T. Managing Student Discipline and Behaviour in Multicultural Classrooms. In Integrating Multicultural Education into the Curriculum for Decolonisation: Benefits and Challenges; Makhalemele, T.J., Tlale, L.D.N., Eds.; Nova: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kawagley, A.O.; Barnhardt, R. Education Indigenous to Place: Western Science Meets Native Reality. Alaska Native Knowledge Network. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 1998, 36, 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, A.J.; Eckert, L.E.; Lane, J.; Young, N.; Hinch, S.G.; Darimont, C.T.; Cooke, S.J.; Ban, N.C.; Marshall, A. “Two-Eyed Seeing”: An Indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management. Fish Fish. 2021, 22, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Alaskans Institute Dialogue Agreements. “Alaska Native Dialogues on Racial Equity” Project; Alaskans Institute: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.; Bifelt, J.; Attla, A.; Turco, K.; MacManus, S. Sled dog husbandry as approach to supporting transfer of traditional knowledge and resilience to at risk youth in rural Alaska. In One Arctic—One Health Conference; Finnish Food Authority Research Reports: Seinäjoki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rivkin, I.; Trimble, J.; Lopez, E.D.S.; Johnson, S.; Orr, E.; Allen, J. Disseminating research in rural Yup’ik communities: Challenges and ethical considerations in moving from discovery to intervention development. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 20958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Newman, J.; Rivkin, I.; Brooks, C.; Turco, K.; Bifelt, J.; Ekada, L.; Philip, J. Indigenous Knowledge: Revitalizing Everlasting Relationships between Alaska Natives and Sled Dogs to Promote Holistic Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010244

Newman J, Rivkin I, Brooks C, Turco K, Bifelt J, Ekada L, Philip J. Indigenous Knowledge: Revitalizing Everlasting Relationships between Alaska Natives and Sled Dogs to Promote Holistic Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010244

Chicago/Turabian StyleNewman, Janessa, Inna Rivkin, Cathy Brooks, Kathy Turco, Joseph Bifelt, Laura Ekada, and Jacques Philip. 2023. "Indigenous Knowledge: Revitalizing Everlasting Relationships between Alaska Natives and Sled Dogs to Promote Holistic Wellbeing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010244

APA StyleNewman, J., Rivkin, I., Brooks, C., Turco, K., Bifelt, J., Ekada, L., & Philip, J. (2023). Indigenous Knowledge: Revitalizing Everlasting Relationships between Alaska Natives and Sled Dogs to Promote Holistic Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010244