Differences in the Prevalence and Profile of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorders—Results from the Singapore Mental Health Study 2016

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures—World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0

2.3. Other Questionnaires

2.4. Statistical Analysis

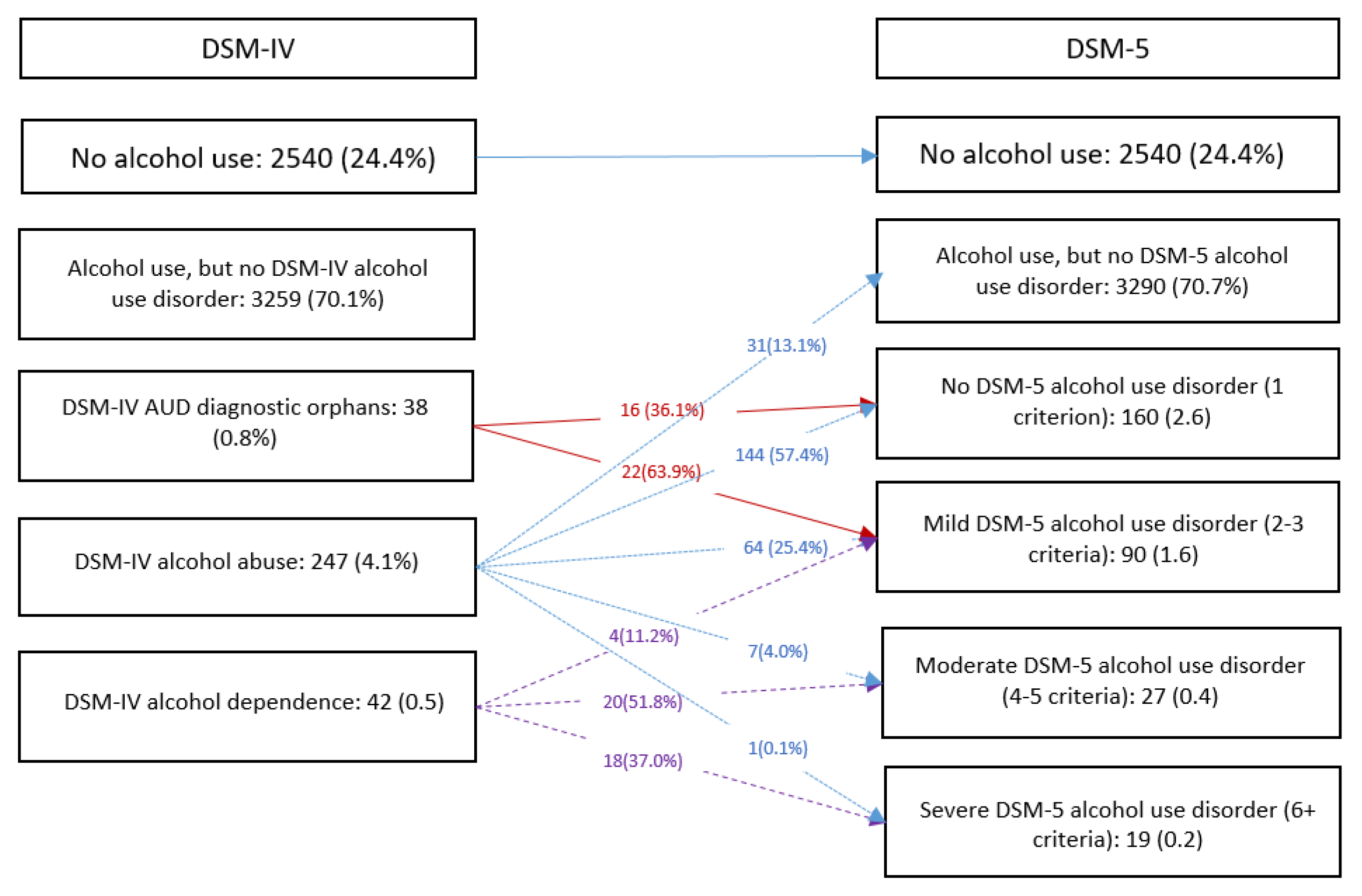

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Sociodemographic Correlates of DSM 5 AUD in Singapore

4.2. Clinical and Functional Correlates of DSM 5 AUD in Singapore

4.3. Are DSM 5 Diagnostic Orphans a Cause for Concern?

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sayette, M.A.; Creswell, K.G.; Dimoff, J.D.; Fairbairn, C.E.; Cohn, J.F.; Heckman, B.W.; Kirchner, T.R.; Levine, J.M.; Moreland, R.L. Alcohol and group formation: A multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Degenhardt, L.; Charlson, F.; Ferrari, A.; Santomauro, D.; Erskine, H.; Mantilla-Herrara, A.; Whiteford, H.; Leung, J.; Naghavi, M.; Griswold, M.; et al. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 987–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barrio, P.; Reynolds, J.; García-Altés, A.; Gual, A.; Anderson, P. Social costs of illegal drugs, alcohol and tobacco in the European Union: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017, 36, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pierucci-Lagha, A.; Gelernter, J.; Feinn, R.; Pearson, D.; Pollastri, A.; Farrer, L.; Kranzler, H.R. Diagnostic reliability of the Semi-Structured Assessment for Drug Dependence and Alcoholism (SSADDA). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005, 80, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasin, D.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Keyes, K.; Ogburn, E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10). Addiction 2006, 101 (Suppl. 1), 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.S.; Steinley, D.L.; Verges, A.; Sher, K.J. The proposed 2/11 symptom algorithm for DSM-5 substance-use disorders is too lenient. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 2008–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ray, L.A.; Miranda, R., Jr.; Chelminski, I.; Young, D.; Zimmerman, M. Diagnostic orphans for alcohol use disorders in a treatment-seeking psychiatric sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 96, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasin, D.S.; O’Brien, C.P.; Auriacombe, M.; Borges, G.; Bucholz, K.; Budney, A.; Compton, W.M.; Crowley, T.; Ling, W.; Petry, N.M.; et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 834–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartoli, F.; Carra, G.; Crocamo, C.; Clerici, M. From DSM-IV to DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: An overview of epidemiological data. Addict. Behav. 2015, 41, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, T.; Chiu, W.T.; Glantz, M.; Kessler, R.C.; Lago, L.; Sampson, N.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Florescu, S.; Moskalewicz, J.; Murphy, S.; et al. A cross-national examination of differences in classification of lifetime alcohol use disorder between DSM-IV and DSM-5: Findings from the World Mental Health Survey. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singapore Department of Statistics. Population Trends. 2019. Available online: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-media/files/publications/population/population2019.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Lee, Y.Y.; Wang, P.; Abdin, E.; Chang, S.; Shafie, S.; Sambasivam, R.; Tan, K.B.; Tan, C.; Heng, D.; Vaingankar, J.; et al. Prevalence of binge drinking and its association with mental health conditions and quality of life in Singapore. Addict. Behav. 2019, 100, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, M.; Abdin, E.; Vaingankar, J.; Phua, A.M.; Tee, J.; Chong, S.A. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use disorders in the Singapore Mental Health Survey. Addiction 2012, 107, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, M.; Abdin, E.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Shafie, S.; Chua, B.Y.; Sambasivam, R.; Zhang, Y.J.; Shahwan, S.; Chang, S.; Chua, H.C.; et al. Tracking the mental health of a nation: Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in the second Singapore mental health study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kessler, R.C.; Ustun, T.B. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 13, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Frecker, R.C.; Fagerstrom, K.O. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991, 86, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwan, S.; Abdin, E.; Shafie, S.; Chang, S.; Sambasivam, R.; Zhang, Y.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Teo, Y.Y.; Heng, D.; Chong, S.A.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of smoking and nicotine dependence: Results of a nationwide cross-sectional survey among Singapore residents. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdin, E.; Chong, S.A.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Shafie, S.; Verma, S.; Luo, N.; Tan, K.B.; James, L.; Heng, D.; Subramaniam, M. Impact of mental disorders and chronic physical conditions on quality-adjusted life years in Singapore. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brazier, J.E.; Roberts, J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med. Care 2004, 42, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghandour, L.A.; Anouti, S.; Afifi, R.A. The impact of DSM classification changes on the prevalence of alcohol use disorder and ‘diagnostic orphans’ in Lebanese college youth: Implications for epidemiological research, health practice, and policy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.A.; Krause, N.; Liang, J.; McGeever, K. Age differences in long-term patterns of change in alcohol consumption among aging adults. J. Aging Health 2011, 23, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delker, E.; Brown, Q.; Hasin, D.S. Alcohol consumption in demographic subpopulations: An epidemiologic overview. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Merrill, J.E.; Carey, K.B. Drinking Over the Lifespan: Focus on College Ages. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kendler, K.S.; Lönn, S.L.; E Salvatore, J.E.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. The impact of parenthood on risk of registration for alcohol use disorder in married individuals: A Swedish population-based analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Jenkins, M.; Glaser, D. Gender differences in risk assessment: Why do women take fewer risks than men? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2006, 1, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, D.K.; Cheng, A.; Lee, C.S.; Takamatsu, S.; Gordon, D. “Man-ing” up and getting drunk: The role of masculine norms, alcohol intoxication, and alcohol-related problems among college men. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 24, 981–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.E. Associations between socioeconomic factors and alcohol outcomes. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.O.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Kosterman, R.; Small, C.M.; Hawkins, J.D. Educational inequalities in the co-occurrence of mental health and substance use problems, and its adult socioeconomic consequences: A longitudinal study of young adults in a community sample. Public Health 2013, 127, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murakami, K.; Hashimoto, H. Associations of education and income with heavy drinking and problem drinking among men: Evidence from a population-based study in Japan. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Almeida, D.M.; Neupert, S.D.; Ettner, S.L. Socioeconomic status and health: A micro-level analysis of exposure and vulnerability to daily stressors. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lincoln, A.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Cheng, D.M.; Lloyd-Travaglini, C.; Caruso, C.; Saitz, R.; Samet, J.H. Impact of health literacy on depressive symptoms and mental health-related: Quality of life among adults with addiction. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Magaña, J.J.; Gonzalez-Castro, T.B.; Genís-Mendoza, A.D.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Saucedo-Uribe, E.; Rodríguez-Mayoral, O.; Lanzagorta, N.; Escamilla, M.; Macías-Kauffer, L.; et al. Exploratory analysis of polygenic risk scores for psychiatric disorders: Applied to dual diagnosis. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2019, 71, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, S.; Akel, M.; Haddad, C.; Fares, K.; Sacre, H.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. Factors associated with alcohol use disorder: The role of depression, anxiety, stress, alexithymia and work fatigue- a population study in Lebanon. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Subramaniam, M.; Abdin, E.; Picco, L.; Pang, S.; Shafie, S.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Kwok, K.W.; Verma, K.; Chong, S.A. Stigma towards people with mental disorders and its components – a perspective from multi-ethnic Singapore. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Soh, K.C.; Lim, W.S.; Cheang, K.M.; Chan, K.L. Stigma towards alcohol use disorder: Comparing healthcare workers with the general population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2019, 8, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, V.; Gomez, B.; Koh, P.K.; Ng, A.; Guo, S.; Kandasami, G.; Wong, K.E. Treatment outcome and its predictors among Asian problem drinkers. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013, 32, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, I.A.; Shandro, J.R.; Montgomery, M.; Polansky, R.; Sachs, C.J.; Duber, H.C.; Weaver, L.M.; Heins, A.; Owen, H.S.; Josephson, E.B.; et al. Effectiveness of SBIRT for Alcohol Use Disorders in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 18, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuma-Guerrero, P.J.; Lawson, K.A.; Velasquez, M.M.; von Sternberg, K.; Maxson, T.; Garcia, N. Screening, brief intervention, and referral for alcohol use in adolescents: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, I.R.; Agarwal, V.; Nah, G.; Dukes, J.W.; Vittinghoff, E.; Dewland, T.A.; Marcus, G.M. Alcohol abuse and cardiac disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.L.; King, C. Self-report of alcohol use for pain in a multi-ethnic community sample. J. Pain 2009, 10, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jochum, T.; Boettger, M.K.; Burkhardt, C.; Juckel, G.; Bär, K.-J. Increased pain sensitivity in alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV abuse criteria Drinking interfered with your work | 75 | 42.9 |

| Drinking resulted in legal problems | 42 | 24.0 |

| Drank in situations where you could get hurt | 39 | 22.3 |

| Drinking caused social or interpersonal problems | 30 | 17.1 |

| DSM-IV | DSM-5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age group | ||||

| 18–34 | 131 | 7.2 | 71 | 3.8 |

| 35–49 | 81 | 5.5 | 36 | 2.3 |

| 50–64 | 54 | 2.6 | 20 | 1.2 |

| 65+ | 23 | 1.2 | 9 | 0.5 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 235 | 7.5 | 106 | 3.5 |

| Female | 54 | 1.9 | 30 | 1.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Chinese | 74 | 4.4 | 36 | 2.1 |

| Malay | 75 | 4.4 | 38 | 2.4 |

| Indian | 105 | 6.3 | 49 | 3.0 |

| Others | 35 | 6.5 | 13 | 2.4 |

| Marital | ||||

| Never married | 107 | 6.2 | 59 | 3.5 |

| Married | 156 | 4.0 | 67 | 1.7 |

| Divorced/separated | 21 | 6.1 | 9 | 2.5 |

| Widowed | 5 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary and below | 37 | 4.0 | 17 | 2.2 |

| Secondary | 80 | 4.5 | 43 | 2.7 |

| Pre-U/Junior College | 5 | 1.2 | 5 | 2.0 |

| Vocational/ITE | 46 | 10.0 | 21 | 2.9 |

| Diploma | 54 | 5.2 | 24 | 2.5 |

| University | 67 | 4.4 | 26 | 1.8 |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 236 | 5.4 | 107 | 2.5 |

| Economically inactive | 31 | 1.6 | 16 | 1.2 |

| Unemployed | 22 | 7.7 | 13 | 3.7 |

| Household Income (SGD/month) | ||||

| Below 2000 | 55 | 5.1 | 40 | 2.4 |

| 2000–3999 | 70 | 5.3 | 34 | 2.0 |

| 4000–5999 | 43 | 2.7 | 30 | 2.3 |

| 6000–9999 | 52 | 5.8 | 21 | 3.0 |

| 10,000 and above | 50 | 4.7 | 15 | 1.8 |

| DSM-IV mental disorders | ||||

| MDD | 47 | 19.5 | 29 | 23.7 |

| Bipolar disorder | 28 | 7.1 | 22 | 13.0 |

| GAD | 16 | 3.7 | 13 | 7.2 |

| OCD | 28 | 9.1 | 20 | 13.2 |

| Treatment gap | 273 | 95.3 | 125 | 92.3 |

| Suicidality | 58 | 20.4 | 36 | 24.3 |

| Nicotine dependence | 62 | 20.1 | 33 | 22.5 |

| DSM-IV | DSM-5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | p Value | AOR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–34 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| 35–49 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.2 | 0.219 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.2 | 0.145 |

| 50–64 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.4 | <0.001 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.001 |

| 65+ | 0.1 | 0.03–0.3 | <0.001 | 0.1 | 0.01–0.4 | 0.002 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Female | 0.3 | 0.2–0.4 | <0.001 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.6 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Chinese | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Malay | 0.7 | 0.5–1.1 | 0.155 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.5 | 0.644 |

| Indian | 1.3 | 0.9–1.8 | 0.206 | 1.4 | 0.9–2.2 | 0.164 |

| Others | 1.8 | 1.1–3.0 | 0.029 | 1.3 | 0.6–2.9 | 0.530 |

| Marital | ||||||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Never married | 1.0 | 0.6–1.8 | 0.981 | 1.3 | 0.7–2.6 | 0.409 |

| Divorced/separated | 1.6 | 0.7–3.7 | 0.237 | 1.4 | 0.5–4.1 | 0.567 |

| Widowed | 0.7 | 0.1–4.1 | 0.715 | 0.1 | 0.01–0.8 | 0.028 |

| Education | ||||||

| University | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Primary and below | 4.0 | 1.8–9.3 | 0.001 | 5.7 | 1.8–17.9 | 0.003 |

| Secondary | 2.3 | 1.2–4.4 | 0.011 | 3.6 | 1.5–8.6 | 0.005 |

| Pre-U/Junior College | 0.5 | 0.1–2.5 | 0.429 | 1.9 | 0.4–7.9 | 0.389 |

| Vocational/ITE | 2.7 | 1.4–5.3 | 0.005 | 1.6 | 0.6–3.8 | 0.339 |

| Diploma | 1.5 | 0.8–2.7 | 0.186 | 1.2 | 0.5–3.1 | 0.672 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Economically inactive | 0.4 | 0.2–0.9 | 0.030 | 0.4 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.060 |

| Unemployed | 1.4 | 0.7–3.0 | 0.358 | 1.4 | 0.5–3.7 | 0.489 |

| Household Income (SGD/month) | ||||||

| Below 2000 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| 2000–3999 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.3 | 0.272 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.2 | 0.151 |

| 4000–5999 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 | 0.005 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.7 | 0.502 |

| 6000–9999 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.9 | 0.861 | 1.2 | 0.5–3.0 | 0.753 |

| 10,000 and above | 0.9 | 0.4–2.0 | 0.855 | 0.8 | 0.3–2.2 | 0.700 |

| DSM-IV AUD | DSM-5 AUD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | p Value | AOR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| No MDD | Ref. | |||||

| MDD | 4.1 | 2.4–7.0 | <0.001 | 4.7 | 2.4–9.0 | 0.001 |

| No Bipolar disorder | Ref. | |||||

| Bipolar disorder | 5.3 | 2.5–11.2 | <0.001 | 10.1 | 4.5–22.7 | <0.001 |

| No GAD | Ref. | |||||

| GAD | 2.3 | 0.9–5.8 | 0.073 | 5.0 | 1.9–13.2 | 0.001 |

| No OCD | Ref. | |||||

| OCD | 2.6 | 1.4–5.1 | 0.003 | 3.7 | 1.7–8.0 | 0.001 |

| No suicidality | Ref. | |||||

| Suicidality | 3.1 | 1.9–5.2 | <0.001 | 3.3 | 1.7–6.4 | <0.001 |

| No nicotine dependence | Ref. | |||||

| Nicotine dependence | 5.8 | 3.5–10.1 | <0.001 | 5.6 | 2.8–11.1 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Subramaniam, M.; Abdin, E.; Kong, A.M.C.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Jeyagurunathan, A.; Shafie, S.; Sambasivam, R.; Fung, D.S.S.; Verma, S.; Chong, S.A. Differences in the Prevalence and Profile of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorders—Results from the Singapore Mental Health Study 2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010285

Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Kong AMC, Vaingankar JA, Jeyagurunathan A, Shafie S, Sambasivam R, Fung DSS, Verma S, Chong SA. Differences in the Prevalence and Profile of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorders—Results from the Singapore Mental Health Study 2016. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010285

Chicago/Turabian StyleSubramaniam, Mythily, Edimansyah Abdin, Alexander Man Cher Kong, Janhavi Ajit Vaingankar, Anitha Jeyagurunathan, Saleha Shafie, Rajeswari Sambasivam, Daniel Shuen Sheng Fung, Swapna Verma, and Siow Ann Chong. 2023. "Differences in the Prevalence and Profile of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorders—Results from the Singapore Mental Health Study 2016" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010285