Risk Perception of COVID-19 as a Cause of Minority Ethnic Community Tourism Practitioners’ Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies: A Case Study in Gansu Based on Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

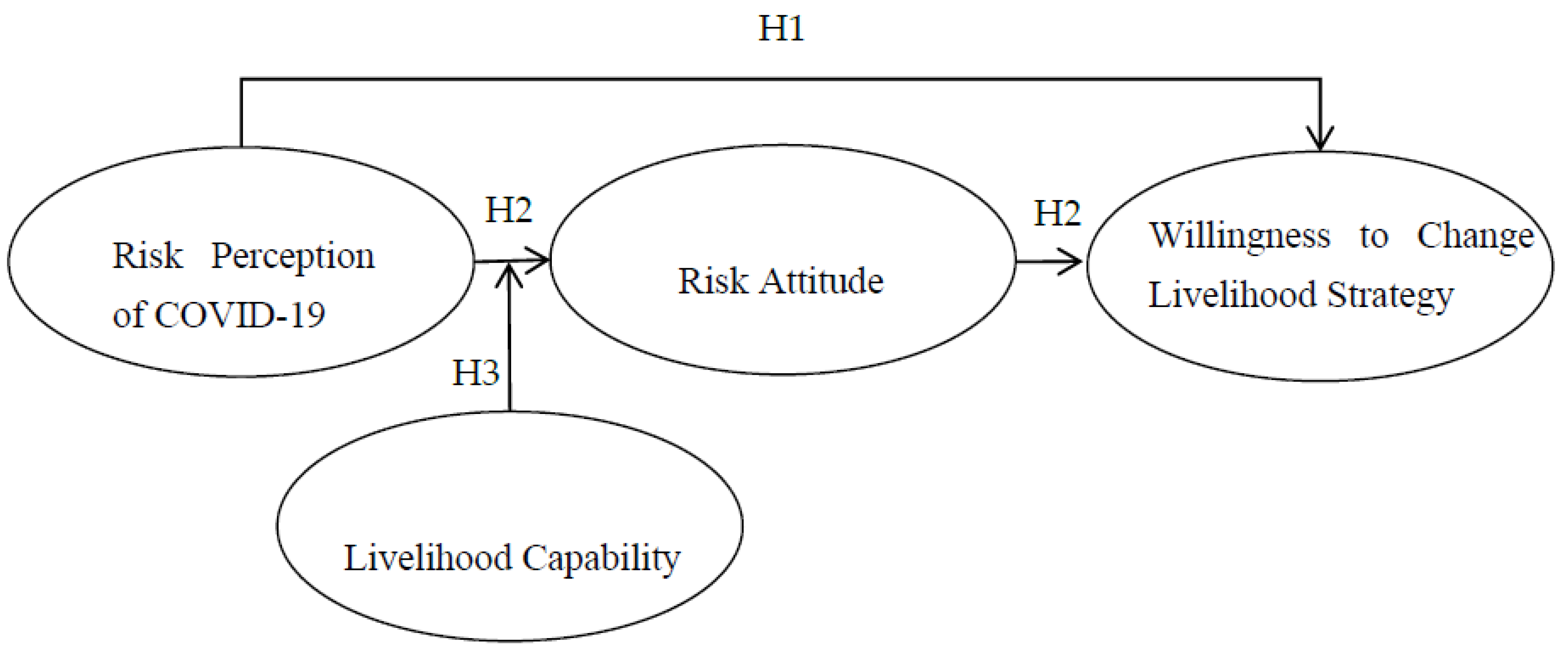

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Risk Perception of COVID-19 and Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies

2.2. Mediation Effect of Risk Attitude

2.3. Moderation Effect of Livelihood Capacity

2.4. Moderated Mediating Effect of Livelihood Capacity

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Research Objects

3.2. Basic Sample Description

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

4.2. Reliability and Validity Test

4.3. Hypothesis Test

4.3.1. Test of Main Effect

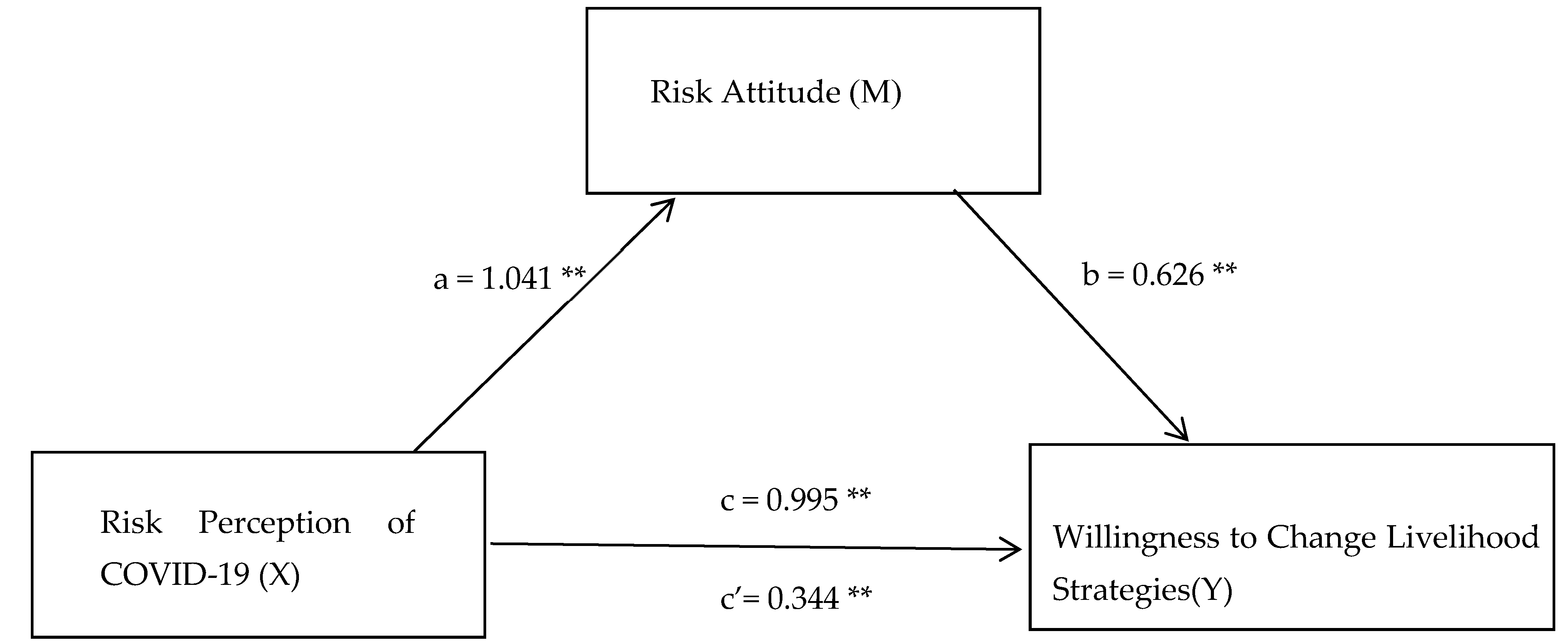

4.3.2. Mediation Effect Test

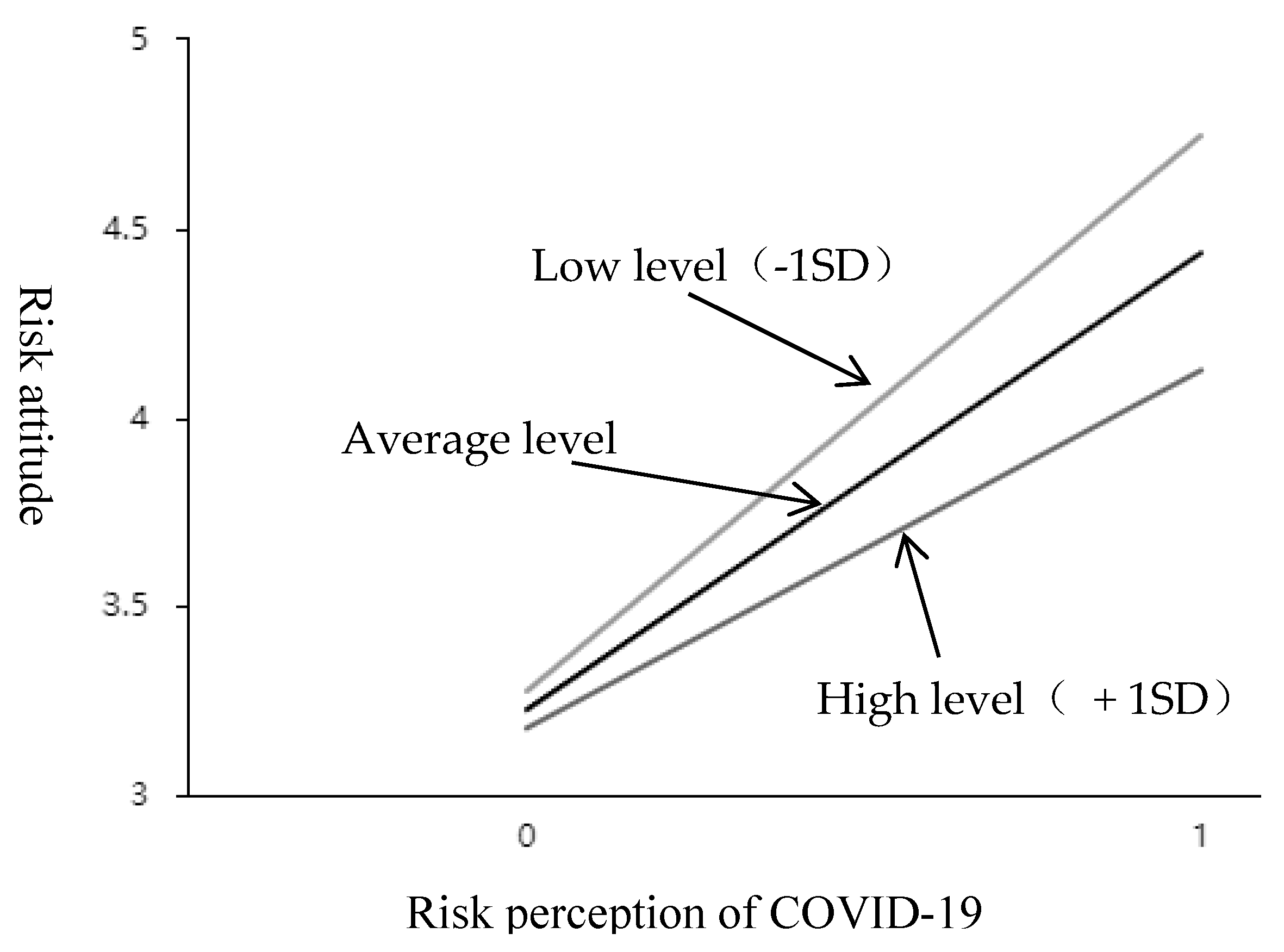

4.3.3. Moderation Effect Test

4.3.4. Moderated Mediation Effect Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Discussion

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2.2. Management Implications

5.2.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Poudel, S. Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1344–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jill, M.; Steve, L. Care homes: Averting market failure in a post-COVID-19 world. BMJ 2021, 372, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio Duro, J.; Perez-Laborda, H.; Turrion-Prats, J.; Fernández-Fernández, M. COVID-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.C.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sha, H.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H. Exploring the Relationship between Perceived Community Support and Psychological Well-Being of Tourist Destinations Residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. The Spatial Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of the Coupling Relationship between Tourism Industry and Rural Sustainable Livelihoods: Take the Zhangiiajie Area as an Example. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Lin, X.; Xu, J. The Resilience of Smallholders: A Constructed Representation of Interactions between Individuals, Society and the State. Issues Agric. Econ. 2022, 1, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nigel, L.W.; Philipp, W.; Nicole, F. Tourism and the COVID-(Mis)infodemic. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Li, G. The impact of tourism development on changes of households’ livelihood and community tourism effect: A case study based on the perspective of tourism development mode. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1709–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Kuang, X.; Huang, G.; Li, X. Effects of Livelihood Capital and Livelihood Capability on the Choice of Tourism Livelihood Strategies in Ethnic Areas. Luojia Manag. Rev. 2021, 3, 168–184. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Xie, H. Influence of the Farmer’s Livelihood Assets on Livelihood Strategies in the Western Mountainous Area, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Xiao, Y. Impact of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital Differences on Their Livelihood Strategies in Three Gorges Reservoir Area. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; OuYang, C.; Xu, X.; Jia, Y. Study on farmers’ willingness to change livelihood strategies under the background of rural tourism. China Popul. Resour. Env. 2020, 30, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; LI, W.; Leng, G.; Qiu, H. Impact of poverty alleviation relocation on livelihood capital and livelihood strategy of poor households--Analysis based on three waves of microdata from 16 counties in 8 province. China Popul. Resour. Env. 2020, 30, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Saikia, U.; Hay, I. Impact of Perceived Livelihood Risk on Livelihood Strategies: A Case Study in Shiyang River Basin, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, D.; Liu, Y.; Gao, T.; Liu, X. The Association between Risk Perception of COVID-19 and Hoarding Behavior: The Mediating Role of Security and the Moderating Role of Life History Strategy. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 30, 856–860. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Q. Research on the Impact of Media Credibility on Risk Perception of COVID-19 and the Sustainable Travel Intention of Chinese Residents Based on an Extended TPB Model in the Post-Pandemic Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elke, U.W.; Ann-Renée, B.; Nancy, E.B. A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2002, 15, 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, A.; Wei, Y.; Zhong, F.; Wang, P. How do climate change perception and value cognition affect farmers’ sustainable livelihood capacity? An analysis based on an improved DFID sustainable livelihood framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, L.; Nguyễn, T.T.; Nazan, C.; Liu, J. Factors influencing the livelihood strategy choices of rural households in tourist destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 875–896. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis. IDS Work. Paper. 1998, 72, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- He, A.; Yang, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z. Impact of Rural Tourism Development on Farmer’S Livelihoods—A Case Study of Rural Tourism Destinations in Northern Slop of Qinling Mountains. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T.C.H.; Wall, G. Tourism as a sustainable livelihood strategy. Tourism Management. 2009, 30, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainza, P.M.A.; Woloshchuk, C.J.; Rodríguez-Crespo, A.; Louden, J.E.; Cooper, T.V. Influence of suicidality on adult perceptions of COVID-19 risk and guideline adherence. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 308, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, L.A.; Epstein, S. Cognitive-experiential self-theory and subjective probability: Further evidence for two conceptual systems. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S. Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. Am. Psychol. 1994, 49, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, B.; Jonas, D.; Carla, K.; Sebastian, L. Sentiment and firm behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 24, 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.Y.; Kevin Y., K. Island ferry travel during COVID-19: Charting the recovery of local tourism in Hong Kong. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, J. Traditional Cultural Adaptation of Residents in an Ethnic Tourism Community: Based on Personal Construction Theory. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, I.; Blume, M.E. The demand for risky assets. Am. Econ. Rev. 1975, 65, 900–922. [Google Scholar]

- Hans, P.B. Risk Attitudes of Rural Households in Semi-Arid Tropical India. Econ. Political Wkly. 1978, 13, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, E.P. Using cognitive theory to explain entrepreneurial risk-taking: Challenging conventional wisdom. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 425–438. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Tong, Z.; Xu, S. Risk attitudes and household consumption behavior: Evidence from China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 922690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Lam, C.F. Travel Anxiety, Risk Attitude and Travel Intentions towards “Travel Bubble” Destinations in Hong Kong: Effect of the Fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushi, A.; Yassin, Y.; Khan, A.; Yezli, S.; Almuzaini, Y. Knowledge, Attitude, and Perceived Risks Towards COVID-19 Pandemic and the Impact of Risk Communication Messages on Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 5, 2811–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldegebrial, Z.; Guido, V.H.; Girmay, T.; Hossein, A.; Stijn, S. Impacts of Socio-Psychological Factors on Actual Adoption of Sustainable Land Management Practices in Dryland and Water Stressed Areas. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2963. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, X. Influence of Herdsmen’ risk attitude on livestock reduction decision and behavior. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Beca-Martínez, M.T.; Romay-Barja, M.; Falcón-Romero, M.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Benito-Llanes, A.; Forjaz, M.J. Compliance with the main preventive measures of COVID-19 in Spain: The role of knowledge, attitudes, practices, and risk perception. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, C.; Chen, H. Rural Tourism Intentions of Urban Residents in the Post-epidemic Era from the Perspective of Social Capital. J. Bus. Econ. 2022, 42, 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, M.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, J.T. Power, coercive actions, and aggression. Int. Rev. Sociol. 1993, 4, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J. Improve or damage: The effect on livelihood capability of rural households of Relocation and Settlement Project. J. China Agric. Univ. 2019, 24, 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Song, N.; Ma, N.; Sultanaliev, A.; Ma, J.; Xue, B.; Fahad, S. An Assessment of Poverty Alleviation Measures and Sustainable Livelihood Capability of Farm Households in Rural China: A Sustainable Livelihood Approach. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V.; Donizzetti, A.R.; Park, M.S. Validation and Psychometric Evaluation of the COVID-19 Risk Perception Scale (CoRP): A New Brief Scale to Measure Individuals’’ Risk Perception. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchardt, T.; Le, G.J.; Piachaud, D. Social Exclusion in Britain 1991–1995. Soc. Policy Adm. 1999, 33, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda-Parr, S. The Human Development Paradigm: Operationalizing Sen’ S Ideas on Capabilities. Fem. Econ. 2003, 9, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongna, A.; Sun, J. Tourism livelihood transition and rhythmic sustainability: The case of the Reindeer Evenki in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 94, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, M.; Corsale, A. Rural tourism and livelihood strategies in Romania. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Wu, G.; Yuan, M.; Zhou, S. Save lives or save livelihoods? A cross-country analysis of COVID-19 pandemic and economic growth. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 197, 221–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, W.; Luo, J. Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak Risk Perception on Willingness to Consume Products from Restaurants: Mediation Effect of Risk Attitude. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Kerstetter, D. Rural Tourism and Livelihood Change: An Emic Perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 43, 416–437. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Y.; Wu, K.; Lin, K. Life or Livelihood? Mental Health Concerns for Quarantine Hotel Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephany, F.; Dunn, M.; Sawyer, S.; Lehdonvirta, V. Distancing Bonus or Downscaling Loss? The Changing Livelihood of Us Online Workers in Times of COVID-19. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armita, K.; Huyen, T.K.L.; Harvey, J.M. What Is Essential Travel? Socioeconomic Differences in Travel Demand in Columbus, Ohio, during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2022, 112, 1023–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Kaili, W.; Sanjana, H.; Khandker, N.H. What happens when post-secondary programmes go virtual for COVID-19? Effects of forced telecommuting on travel demand of post-secondary students during the pandemic. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 166, 62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ljubotina, P.; Raspor, A. Recovery of Slovenian Tourism After COVID-19 and Ukraine Crisis. Economics 2022, 10, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, T.; Saito, H. The COVID-19 pandemic and domestic travel subsidies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 92, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measurement Index | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | 196 | 46.3 |

| F | 227 | 53.7 | |

| Age | Under 18 | 5 | 1.2 |

| 18–25 | 21 | 5 | |

| 26–35 | 76 | 18 | |

| 36–45 | 121 | 28.6 | |

| 46–55 | 126 | 29.8 | |

| Over 56 | 74 | 17.5 | |

| Highest level of education | Junior high school and below | 207 | 48.9 |

| Senior secondary/technical secondary and below | 133 | 31.4 | |

| Junior college | 52 | 12.3 | |

| College or above | 31 | 7.3 | |

| Nation | Han nationality | 96 | 22.7 |

| Tibetans | 202 | 47.8 | |

| Hui nationality | 97 | 22.9 | |

| Bai nationality | 21 | 5 | |

| Others | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Monthly discretionary income | Under 2000 RMB | 58 | 13.7 |

| 2001–5000 RMB | 131 | 31 | |

| 5001–8000 RMB | 152 | 35.9 | |

| Over 8000 RMB | 82 | 19.4 | |

| Case | Labrang Town | 101 | 23.9 |

| Sangke Town | 64 | 15.1 | |

| Langmusi Town | 135 | 31.9 | |

| Gaxiu Village | 30 | 7.1 | |

| Bafang 13 xiang | 93 | 22 |

| Dimension | Items | Std. Estimate | z (CR) | Cronbach’s α | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk perception of COVID-19 | Y1 | 0.688 | 0.71 | 0.765 | 0.523 |

| Y2 | 0.675 | ||||

| Y3 | 0.731 | ||||

| Y4 | 0.786 | ||||

| Y5 | 0.767 | ||||

| Y6 | 0.685 | ||||

| Risk attitude | F1 | 0.895 | 0.878 | 0.895 | 0.706 |

| F2 | 0.882 | ||||

| F3 | 0.727 | ||||

| F4 | 0.845 | ||||

| Livelihood capacity | S1 | 0.736 | 0.751 | 0.788 | 0.574 |

| S2 | 0.765 | ||||

| S3 | 0.749 | ||||

| S4 | 0.803 | ||||

| S5 | 0.733 | ||||

| Willingness to change livelihood strategies | J1 | 0.705 | 0.869 | 0.873 | 0.626 |

| J2 | 0.771 | ||||

| J3 | 0.848 | ||||

| J4 | 0.832 |

| Average Value | SD | Gender | Age | Education | Risk Perception of COVID-19 | Risk Attitude | Livelihood Capacity | Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.535 | 0.499 | |||||||

| Age | 2.561 | 1.11 | 0.033 | ||||||

| Education | 2.915 | 0.881 | −0.03 | 0.238 ** | |||||

| Risk perception of COVID−19 | 3.616 | 0.729 | 0.009 | −0.153 ** | 0.130 * | 0.723 | |||

| Risk attitude | 3.354 | 1.093 | −0.02 | −0.074 | 0.064 | 0.695 ** | 0.84 | ||

| Livelihood capacity | 2.433 | 0.772 | −0.008 | 0.185 ** | −0.112 * | −0.673 ** | −0.450 ** | 0.758 | |

| Willingness to change livelihood strategies | 3.367 | 1.041 | −0.05 | −0.065 | 0.134 * | 0.697** | 0.824 ** | −0.387 ** | 0.791 |

| X→Y | Non-Standardized Path | SE | z (CR) | p | Standardized Path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk perception of COVID-19→Risk attitude | 1.041 | 0.058 | 17.856 | 0 | 0.695 |

| Risk perception of COVID-19→Willingness to change livelihood strategies | 0.344 | 0.058 | 5.942 | 0 | 0.241 |

| Risk attitude→Willingness to change livelihood strategies | 0.626 | 0.039 | 16.21 | 0 | 0.657 |

| Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies | Risk Attitude | Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.232 (−1.132) | −0.412 (−1.909) | 0.026 (0.166) |

| risk perception of COVID-19 | 0.995 ** (17.927) | 1.041 ** (17.806) | 0.344 ** (5.914) |

| risk attitude | 0.626 ** (16.134) | ||

| R 2 | 0.486 | 0.483 | 0.709 |

| Adjust R 2 | 0.484 | 0.481 | 0.708 |

| F | F (1340) = 321.390, p = 0.000 | F (1340) = 317.044, p = 0.000 | F (2339) = 413.406, p = 0.000 |

| Path | c | a | b | a×b | a×b (Boot SE) | a×b (z) | a×b (p) | a×b (95% BootCI) | c’ | Test Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| risk perception of COVID-19→risk attitude→willingness to change livelihood strategies | 0.995 ** | 1.041 ** | 0.626 ** | 0.651 | 0.055 | 11.772 | 0 | 0.354~0.569 | 0.344 ** | Partial mediation |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p | β | |

| Constant | 3.354 | 0.043 | 78.786 | 0.000 ** | - | 30.354 | 0.043 | 78.716 | 0.000 ** | - | 3.226 | 0.047 | 68.685 | 0.000 ** | - |

| Risk perception of COVID-19 | 1.041 | 0.058 | 17.806 | 0.000 ** | 0.695 | 1.075 | 0.079 | 13.575 | 0.000 ** | 0.717 | 1.209 | 0.08 | 15.165 | 0.000 ** | 0.806 |

| Livelihood capacity | 0.047 | 0.075 | 0.628 | 0.53 | 0.033 | −0.063 | 0.074 | −0.852 | 0.395 | −0.045 | |||||

| Risk perception of COVID-19 * Livelihood capacity | −0.339 | 0.061 | −5.528 | 0.000 ** | −0.257 | ||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.483 | 0.483 | 0.526 | ||||||||||||

| Adjust R 2 | 0.481 | 0.48 | 0.522 | ||||||||||||

| F | F (1340) = 317.044, p = 0.000 | F (2339) = 158.437, p = 0.000 | F (3338) = 125.024, p = 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| △R 2 | 0.483 | 0.001 | 0.043 | ||||||||||||

| △F | F (1340) = 317.044, p = 0.000 | F (1339) = 0.395, p = 0.530 | F (1338) = 30.564, p = 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| Mediation Variable | Level | Level Value | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk attitude | Low level (−1SD) | 1.661 | 0.92 | 0.123 | 0.694 | 1.177 |

| Average level | 2.433 | 0.756 | 0.105 | 0.569 | 0.976 | |

| High level (1SD) | 3.204 | 0.593 | 0.094 | 0.43 | 0.794 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, W.; Li, Z.; Bao, Y.; Xia, B. Risk Perception of COVID-19 as a Cause of Minority Ethnic Community Tourism Practitioners’ Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies: A Case Study in Gansu Based on Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010292

Liang W, Li Z, Bao Y, Xia B. Risk Perception of COVID-19 as a Cause of Minority Ethnic Community Tourism Practitioners’ Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies: A Case Study in Gansu Based on Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010292

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Wangbing, Zhao Li, Yinggang Bao, and Bing Xia. 2023. "Risk Perception of COVID-19 as a Cause of Minority Ethnic Community Tourism Practitioners’ Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies: A Case Study in Gansu Based on Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010292

APA StyleLiang, W., Li, Z., Bao, Y., & Xia, B. (2023). Risk Perception of COVID-19 as a Cause of Minority Ethnic Community Tourism Practitioners’ Willingness to Change Livelihood Strategies: A Case Study in Gansu Based on Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010292