Impact of Environmental Tax on Corporate Sustainable Performance: Insights from High-Tech Firms in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

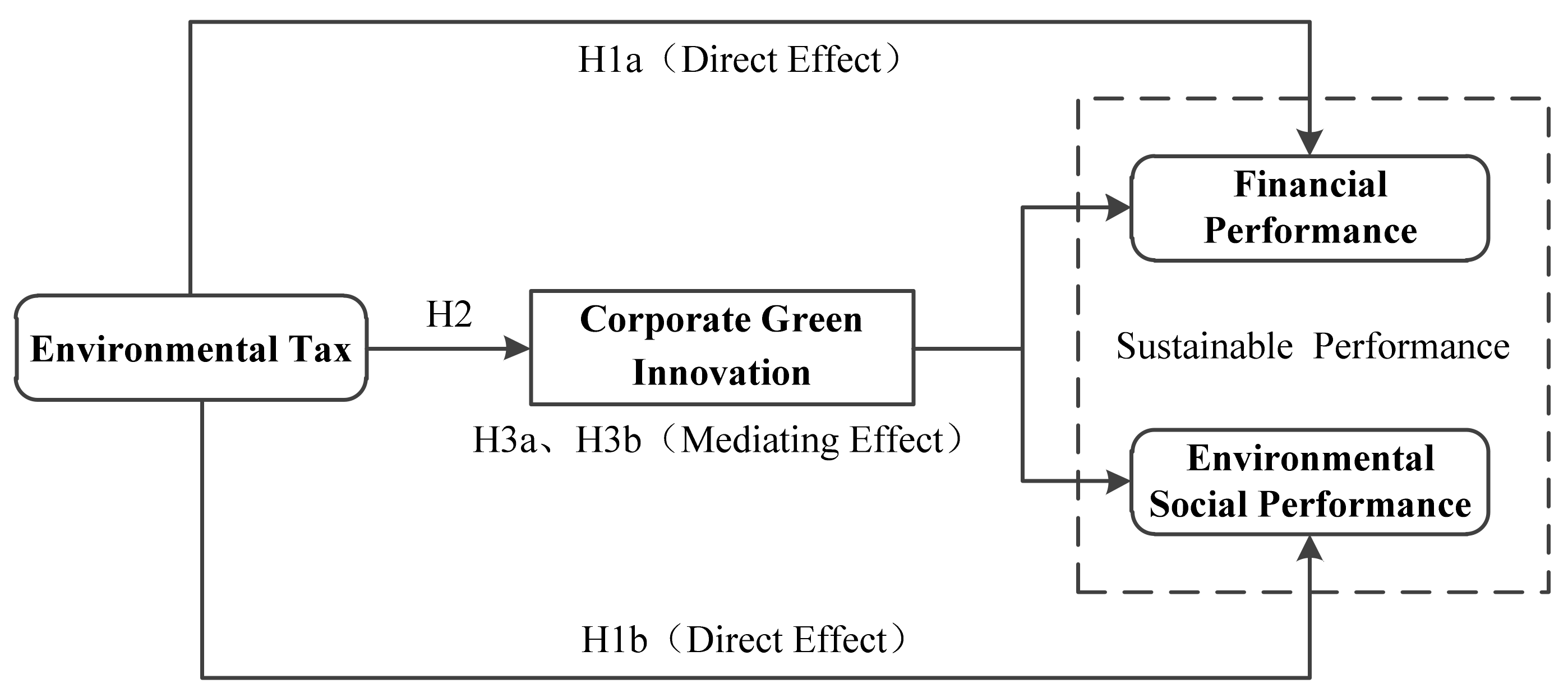

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypothesis

2.1. Corporate Sustainable Performance

2.2. Environmental Tax and Corporate Sustainable Performance

2.2.1. Environmental Tax and Corporate Financial Performance

2.2.2. Environmental Tax and Corporate Environmental Social Performance

2.3. Environmental Tax and Corporate Green Innovation

2.4. The Mediating Role of Corporate Green Innovation

3. Data and Variables

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Environmental Tax

3.2.2. Corporate Sustainable Performance

3.2.3. Corporate Green Innovation

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Model Specification

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

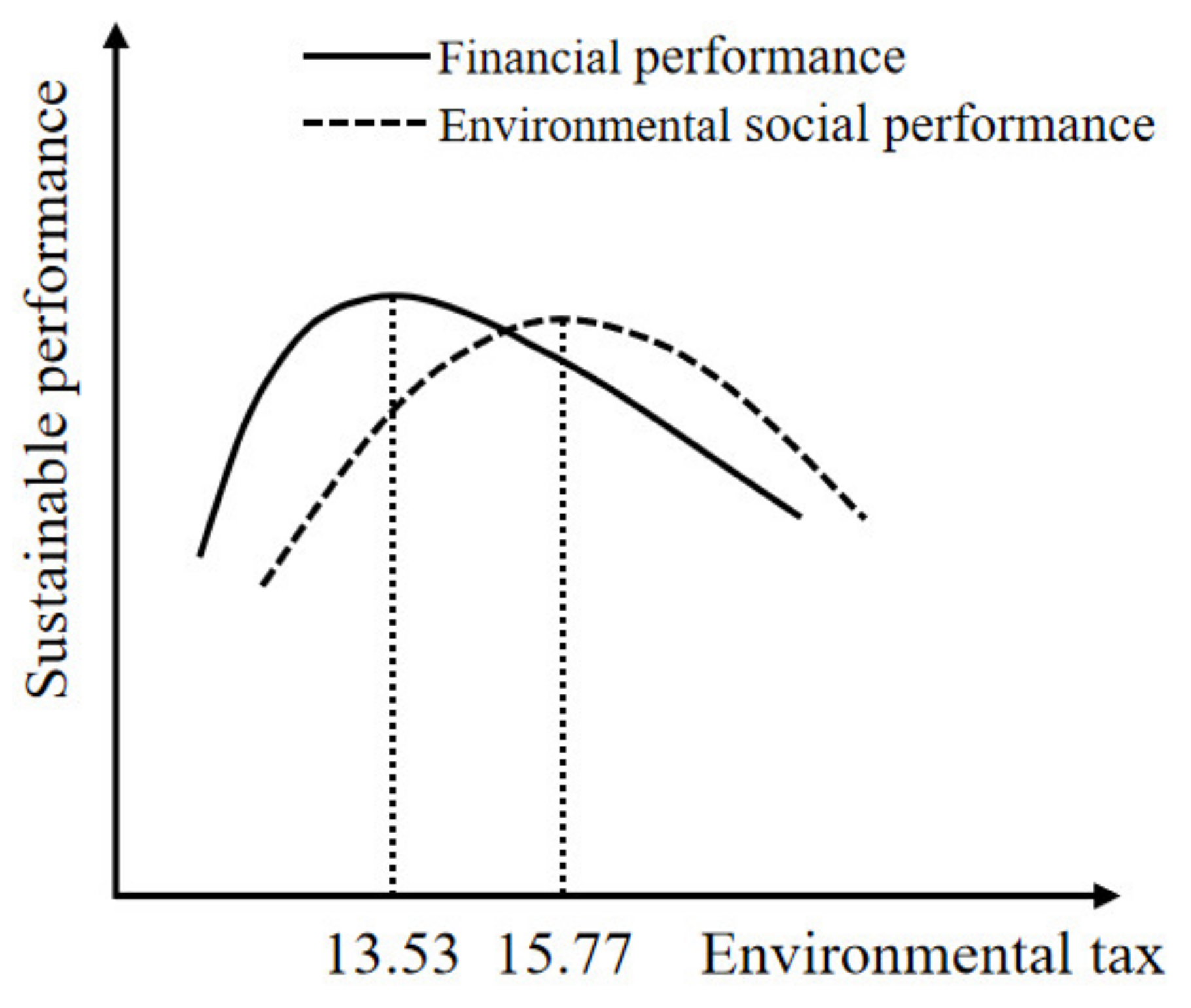

4.2. Regression Analysis

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Cai, Z.; Wang, L. Chinese firms’ sustainable development—The role of future orientation, environmental commitment, and employee training. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A.-N.; Singh, S.K. Green innovation and organizational performance: The influence of big data and the moderating role of management commitment and HR practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Hoang, T.T.; Zhu, Q. Green process innovation and financial performance: The role of green social capital and customers’ tacit green needs. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huo, J.; Zou, H. Green process innovation, green product innovation, and corporate financial performance: A content analysis method. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Singh, R. The impact of leanness and innovativeness on environmental and financial performance: Insights from Indian SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 212, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, A.; Badir, Y.; Chonglerttham, S. Green innovation and performance: Moderation analyses from Thailand. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Guerrero-Villegas, J.; García-Sánchez, E. Does green innovation affect the financial performance of Multilatinas? The moderating role of ISO 14001 and R&D investment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3286–3302. [Google Scholar]

- Baah, C.; Opoku-Agyeman, D.; Acquah, I.S.K.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E.; Faibil, D.; Abdoulaye, F.A.M. Examining the correlations between stakeholder pressures, green production practices, firm reputation, environmental and financial performance: Evidence from manufacturing SMEs. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farza, K.; Ftiti, Z.; Hlioui, Z.; Louhichi, W.; Omri, A. Does it pay to go green? The environmental innovation effect on corporate financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.F.; Ma, B.; Shahzad, L.; Liu, B.; Ruan, Q. China’s quest for economic dominance and energy consumption: Can Asian economies provide natural resources for the success of One Belt One Road? Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 42, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Huang, L.; Cai, Y. Can environmental tax bring strong porter effect? Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 32246–32260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrizio, S.; Kozluk, T.; Zipperer, V. Environmental policies and productivity growth: Evidence across industries and firms. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 81, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Guan, H. Environmental taxes, technology innovation quality and firm performance in China—A test of effects based on the Porter hypothesis. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Jin, Z. Sustainable supply chain management and organizational performance: The intermediary role of competitive advantage. J. Mgmt. Sustain. 2019, 9, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhu, Q. How Can green innovation solve the dilemmas of “Harmonious Coexistence”? J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa, S.K.; Othman, M. The impact of green human resource management practices on sustainable performance in healthcare organisations: A conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ding, R.; Cui, L.; Lei, Z.; Mou, J. The impact of sharing economy practices on sustainability performance in the Chinese construction industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, C.J.; Pan, J.N. Evaluating environmental performance using statistical process control techniques. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 139, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigou, A.C. The Economics of Welfare; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, B. The influence of Chinese environmental regulation on corporation innovation and competitiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, E.; Bui, L.T.M. Environmental regulation and productivity: Evidence from oil refineries. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2001, 83, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, W. Do environmental regulations impede economic growth? A case study of the metal finishing industry in the South Coast Basin of Southern California. Econ. Dev. Q. 2009, 23, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrunner, P.R. Boon or bane? On productivity and environmental regulation. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2022, 24, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, F.; Sadiq, M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, M.S.; Tran, T.D.; Le Thanh, T. A step toward reducing air pollution in top Asian economies: The role of green energy, eco-innovation, and environmental taxes. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, C. SO2 emission reduction decomposition of environmental tax based on different consumption tax refunds. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, L.; Huang, G.H.; Li, W.; Xie, Y.L. Effects of carbon and environmental tax on power mix planning—A case study of Hebei Province, China. Energy 2018, 143, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, H.; Schopf, M. Unilateral Climate Policy: Harmful or Even Disastrous? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2014, 58, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinn, H.-W. Public policies against global warming: A supply side approach. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2008, 15, 360–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, F.; Withagen, C. Is there really a Green Paradox? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2012, 64, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, G.; Feng, T.; Yuan, C.; Jiang, W. Green innovation to respond to environmental regulation: How external knowledge adoption and green absorptive capacity matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Bi, Q. Can Environmental Taxes Force Corporate Green Innovation? J. Audit Econ. 2019, 34, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, F.; Patino-Echeverri, D. Effects of environmental regulation on firm entry and exit and China’s industrial productivity: A new perspective on the Porter Hypothesis. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2021, 23, 915–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Sun, X. Environmental regulation, green technological innovation and green economic growth. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Cheng, H. Environmental Taxes and Innovation in Chinese Textile Enterprises: Influence of Mediating Effects and Heterogeneous Factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Bi, Q. The study on the backward forcing effect of environmental tax on corporate green transformation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos, I.; Kounetas, K.; Tzelepis, D. Environmental and financial performance. Is there a win-win or a win-loss situation? Evidence from the Greek manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Min, B. Green R&D for eco-innovation and its impact on carbon emissions and firm performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 534–542. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.; Ma, H.; Qi, G.; Tam, V.W. Can political capital drive corporate green innovation? Lessons from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, M.; Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Ning, L. Environmental Legitimacy, Green Innovation, and Corporate Carbon Disclosure: Evidence from CDP China 100. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zeng, S.; Lin, H.; Meng, X.; Yu, B. Can transportation infrastructure pave a green way? A city-level examination in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindman, A.; Soderholm, P. Wind energy and green economy in Europe: Measuring policy-induced innovation using patent data. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.X.; Ma, H.Y.; Chen, H.Q. How Political Connections Affect Corporate Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Subsidies. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2015, 21, 2192–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zheng, M.; Cao, C.; Chen, X.; Ren, S.; Huang, M. The impact of legitimacy pressure and corporate profitability on green innovation: Evidence from China top 100. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.T.; Noordewier, T.G. Environmental management practices and firm financial performance: The moderating effect of industry pollution-related factors. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 175, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Feng, B. Curvilinear Effect and Statistical Test Method in the Management Research. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2022, 25, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, S.; De Luca, F.; Phan, H.-T.-P. Do investors value companies’ mandatory nonfinancial risk disclosure? An empirical analysis of the Italian context after the EU Directive. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2226–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, G. Environmental regulations, green innovation and intelligent upgrading of manufacturing enterprises: Evidence from China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measures | Literature Sources | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental tax (ET) | The natural logarithm of corporate environmental tax plus one | Yu and Cheng [35] | CSMAR Database |

| Green innovation (GI) | The natural logarithm of the number of applications for green invention patents and green utility model patents plus one | Lindman and Soderholm [42] | CNRDS Platform |

| Financial performance (FP) | Return on assets (ROA) | Xie et al. [4] Xie and Zhu [15] | CSMAR Database |

| Environmental Social performance (ESP) | Standardized results of total score of corporate environmental–social responsibility | Xie and Zhu [15] | Hexun Website |

| Firm size (Size) | The natural logarithm of total assets | Lin et al. [44] | CSMAR Database |

| Firm age (Age) | The number of years listed in the Chinese Stock Market at the end of the reporting year | Lin et al. [44] | CSMAR Database |

| TOA | The ratio of operating income to total assets | Lucas and Noordewier [46] | CSMAR Database |

| Asset-liability ratio (Lev) | The ratio of total liabilities to total assets | Xie et al. [4] | CSMAR Database |

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ET | 15.84 | 1.58 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 2. GI | 1.34 | 1.28 | 0.380 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 3. FP | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.117 *** | 0.089 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| 4. ESP | −0.01 | 1.00 | 0.175 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.492 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 5. Age | 12.13 | 6.32 | 0.339 *** | 0.069 ** | −0.064 ** | 0.036 | 1.000 | |||

| 6. Size | 22.42 | 1.15 | 0.782 *** | 0.401 *** | 0.061 ** | 0.202 *** | 0.404 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 7. TOA | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.301 *** | −0.016 | 0.071 ** | 0.085 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.188 *** | 1.000 | |

| 8. Lev | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.435 *** | 0.178 *** | −0.227*** | −0.035 | 0.310 *** | 0.593 *** | 0.211 *** | 1.000 |

| Explained Variables | Green Innovation (GI) | Financial Performance (FP) | Environmental Social Performance (ESP) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Explanatory variables | ||||||||||

| L.ET | 0.170 *** (0.047) | −0.007 * (0.004) | −0.005 (0.004) | −0.007 * (0.004) | −0.036 (0.036) | −0.021 (0.035) | −0.038 (0.037) | |||

| L.ET2 | −0.003 *** (0.001) | −0.025 *** (0.009) | ||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||||

| GI | 0.006 ** (0.003) | 0.002 (0.028) | ||||||||

| GI2 | −0.003 ** (0.001) | 0.005 (0.013) | ||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||

| Size | 0.632 *** (0.038) | 0.502 *** (0.060) | 0.024 *** (0.003) | 0.033 *** (0.005) | 0.034 *** (0.005) | 0.031 *** (0.006) | 0.329 *** (0.033) | 0.337 *** (0.047) | 0.355 *** (0.047) | 0.332 *** (0.049) |

| Age | 0.000 (0.006) | −0.001 (0.007) | −0.001 (0.000) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.006 (0.005) | 0.003 (0.005) | 0.004 (0.005) | 0.003 (0.005) |

| TOA | −0.057 (0.085) | −0.167 * (0.096) | 0.025 ** (0.010) | 0.031 ** (0.013) | 0.029 ** (0.013) | 0.031 ** (0.013) | 0.222 *** (0.068) | 0.220 *** (0.078) | 0.199 *** (0.076) | 0.222 *** (0.079) |

| Lev | −0.407 ** (0.194) | −0.343 (0.217) | −0.175 *** (0.020) | −0.198 *** (0.023) | −0.200 *** (0.023) | −0.198 *** (0.023) | −1.172 *** (0.154) | −1.257 *** (0.158) | −1.277 *** (0.157) | −1.251 *** (0.159) |

| Constant | −13.299 *** (0.821) | −12.547 *** (0.958) | −0.438 *** (0.065) | −0.532 *** (0.084) | −0.669 *** (0.124) | −0.604 *** (0.129) | −7.370 *** (0.756) | −6.544 *** (0.757) | −7.429 *** (1.076) | −7.013 *** (1.104) |

| R2 | 0.397 | 0.417 | 0.228 | 0.247 | 0.256 | 0.253 | 0.273 | 0.292 | 0.299 | 0.292 |

| F-value | 18.73 | 20.84 | 11.72 | 10.04 | 9.42 | 10.27 | 10.05 | 8.4 | 8.25 | 8.23 |

| x2 | 10.30 | 29.23 | 109.58 | 136.41 | 140.62 | 136.61 | 156.32 | 122.13 | 125.36 | 127.25 |

| p-value | 0.067 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Explanatory Variable | Mediator | Explained Variable | Bootstrap Test | Effect Size | Boot Standard Error | Boot CI Lower Limit | Boot CI Upper Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | GI2 | FP | Mediating effect | −0.00038 | 0.00028 | −0.00115 | −0.00001 |

| ET | GI2 | ESP | Mediating effect | 0.00085 | 0.00232 | −0.00244 | 0.00745 |

| Explained Variables | Green Innovation (GI) | Financial Performance (FP) | Environmental Social Performance (ESP) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Explanatory variables | ||||||||||

| L.ET | 0.258 *** (0.079) | −0.011 * (0.006) | −0.011 * (0.006) | −0.009 (0.006) | −0.133 (0.093) | −0.133 (0.093) | −0.147 (0.094) | |||

| L.ET2 | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.007 (0.018) | ||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||||

| GI | −0.005 (0.006) | 0.033 (0.078) | ||||||||

| GI2 | −0.001 (0.002) | 0.006 (0.020) | ||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||

| Size | 1.073 *** (0.076) | 0.786 *** (0.129) | 0.031 *** (0.009) | 0.039 *** (0.014) | 0.039 *** (0.014) | 0.043 ** (0.017) | 0.268 *** (0.072) | 0.390 *** (0.128) | 0.385 *** (0.132) | 0.355 ** (0.153) |

| Age | −0.005 (0.017) | 0.008 (0.019) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.019 (0.020) | 0.015 (0.019) | 0.015 (0.019) | 0.015 (0.020) |

| TOA | 0.158 (0.150) | −0.189 (0.201) | 0.004 (0.021) | 0.035 (0.024) | 0.037 (0.024) | 0.034 (0.023) | −0.155 (0.172) | 0.039 (0.235) | 0.023 (0.242) | 0.048 (0.238) |

| Lev | −0.655 (0.490) | −0.077 (0.545) | −0.179 *** (0.056) | −0.209 *** (0.070) | −0.206 *** (0.069) | −0.212 *** (0.073) | −1.885 *** (0.405) | −2.205 *** (0.502) | −2.227 *** (0.502) | −2.185 *** (0.506) |

| Constant | −25.088 *** (1.851) | −23.781 *** (2.190) | −0.649 *** (0.195) | −0.599 *** (0.212) | −0.775 *** (0.286) | −0.903 ** (0.374) | −5.049 *** (1.766) | −4.575 ** (2.008) | −6.761 ** (2.746) | −5.808 * (3.449) |

| R2 | 0.760 | 0.783 | 0.375 | 0.429 | 0.431 | 0.432 | 0.402 | 0.453 | 0.453 | 0.454 |

| F-value | 53.95 | 71.61 | 12.26 | 16.86 | 16.58 | 15.04 | 5.46 | 4.79 | 4.67 | 4.64 |

| x2 | 7.22 | 4.98 | 27.60 | 20.79 | 24.73 | 22.94 | 26.45 | 24.41 | 30.07 | 25.62 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Explained Variables | Green Innovation (GI) | Financial Performance (FP) | Environmental Social Performance (ESP) | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Explanatory variables | ||||||||||

| L.ET | 0.212 *** (0.056) | −0.008 (0.005) | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.009 (0.005) | 0.009 (0.044) | 0.017 (0.042) | 0.005 (0.045) | |||

| L.ET2 | −0.004 *** (0.001) | −0.030 ** (0.013) | ||||||||

| Mediators | ||||||||||

| GI | 0.009 *** (0.003) | 0.010 (0.031) | ||||||||

| GI2 | −0.004 ** (0.001) | 0.005 (0.017) | ||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||

| Size | 0.577 *** (0.045) | 0.429 *** (0.067) | 0.021 *** (0.003) | 0.032 *** (0.007) | 0.036 *** (0.007) | 0.031 *** (0.007) | 0.330 *** (0.041) | 0.302 *** (0.054) | 0.331 *** (0.056) | 0.295 *** (0.055) |

| Age | −0.002 (0.008) | −0.006 (0.008) | −0.001 * (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.001 * (0.001) | 0.005 (0.007) | −0.001 (0.006) | 0.000 (0.006) | −0.001 (0.007) |

| TOA | 0.029 (0.108) | −0.093 (0.119) | 0.024 * (0.013) | 0.026 (0.018) | 0.022 (0.017) | 0.026 (0.018) | 0.178 ** (0.087) | 0.164 (0.101) | 0.133 (0.097) | 0.165 (0.102) |

| Lev | −0.497 ** (0.231) | −0.451* (0.259) | −0.165 *** (0.023) | −0.194 *** (0.027) | −0.200 *** (0.027) | −0.194 *** (0.027) | −0.939 *** (0.181) | −1.019 *** (0.186) | −1.059 *** (0.185) | −1.009 *** (0.187) |

| Constant | −12.128 *** (0.955) | −11.528*** (1.075) | −0.388 *** (0.071) | −0.505 *** (0.094) | −0.702 *** (0.152) | −0.590 *** (0.154) | −7.421 *** (0.902) | −6.469 *** (0.904) | −6.873 *** (1.259) | −6.172 *** (1.247) |

| R2 | 0.340 | 0.361 | 0.229 | 0.242 | 0.257 | 0.251 | 0.278 | 0.285 | 0.292 | 0.285 |

| F-value | 15.18 | 13.96 | 10.26 | 8.38 | 7.94 | 9.10 | 9.02 | 7.25 | 6.98 | 7.14 |

| x2 | 4.96 | 22.01 | 86.49 | 124.45 | 126.96 | 121.72 | 135.58 | 100.09 | 106.45 | 106.67 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Impact of Environmental Tax on Corporate Sustainable Performance: Insights from High-Tech Firms in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010461

Zhao X, Li J, Li Y. Impact of Environmental Tax on Corporate Sustainable Performance: Insights from High-Tech Firms in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010461

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xiaomin, Jiahui Li, and Yang Li. 2023. "Impact of Environmental Tax on Corporate Sustainable Performance: Insights from High-Tech Firms in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010461

APA StyleZhao, X., Li, J., & Li, Y. (2023). Impact of Environmental Tax on Corporate Sustainable Performance: Insights from High-Tech Firms in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010461