Development and Validation of a Mobile Application as an Adjuvant Treatment for People Diagnosed with Long COVID-19: Protocol for a Co-Creation Study of a Health Asset and an Analysis of Its Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

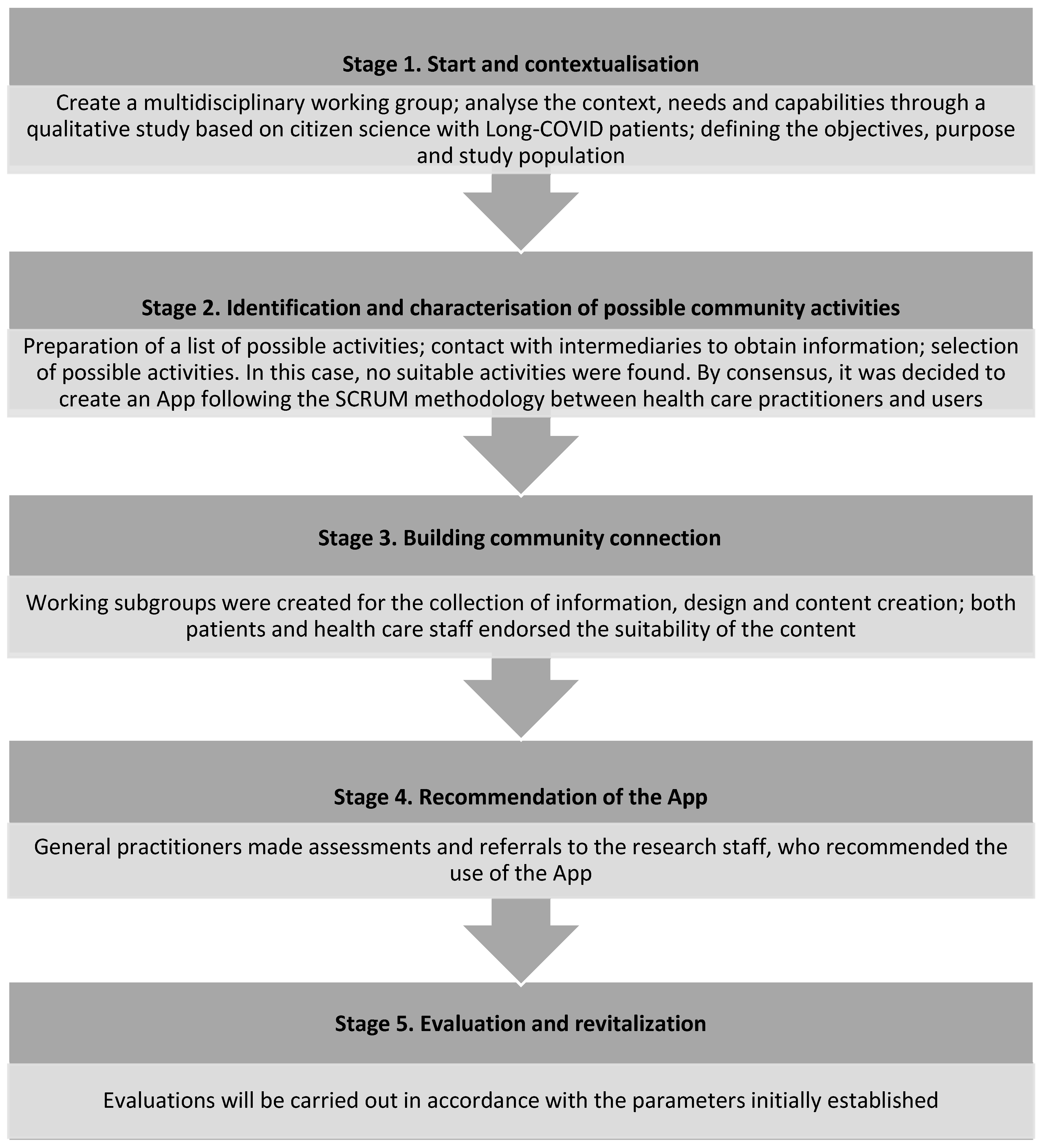

2.1. Methodology to Design and Develop the Community Resource (ReCoVery APP)

2.1.1. Start and Contextualisation

2.1.2. Identification and Characterisation of Possible Community Activities

2.1.3. Building Community Connection

2.1.4. Recommendation of the APP to Patients

2.1.5. Evaluation and Revitalisation

2.2. APP’s Validation, Effectiveness and Cost-Efficiency as a HA

2.2.1. Study Design

2.2.2. Study Population

2.2.3. Sample Size

2.2.4. Patient Inclusion

2.2.5. Randomisation, Allocation and Masking of Study Groups

2.2.6. Intervention

- Diet

- 2.

- Sleep hygiene

- 3.

- Physical exercise

- 4.

- Respiratory physiotherapy

- 5.

- Cognitive exercises

- 6.

- Community resources: socialization and emotional well-being

2.2.7. Variables and Instruments

- -

- Socio-demographic variables: gender, age, civil status, education, household, and occupation. Roles will also be collected using the Spanish version of the Role Checklist, whose test–retest reliability, measured by weighted Kappa, is 0.74 [69,70], an inventory divided into two parts. The first part evaluates the presence of the ten main roles of people’s life over time. Individuals should indicate whether they have performed each of the roles in the past (any time up to the week immediately preceding the assessment), whether they are currently being performed (on the day the checklist is completed and during the seven days prior), and if they plan to perform them in the future (any time from the following day). It is possible to mark more than one time for each role. The second part measures the value that the individual attributes to each role (“Not at all valuable”, “Somewhat valuable”, or “Very valuable”). People should mark the value they consider for each of ten roles, even if they have never played them or do not plan to do so in the future [71].

- -

- Clinical variables: clinical history, contraction of COVID-19, timeline of developing Long COVID, number of residual symptoms, and their severity measured via an analogue visual scale [72], days taken on sick-leave. Residual symptoms include: gastrointestinal symptoms, loss of smell, loss of taste, blurred vision, eye problems (increased dioptre, dry eyes, conjunctivitis), tiredness or fatigue, cough, fever (over 38 °C), low-grade fever (37–38 °C), chills or shivering without fever, bruising, myalgia, headaches, sore throat, dyspnoea, chronic fatigue, dizziness, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, joint pain, chest pain, back pain (cervical, dorsal or lumbar), neurological symptoms (tingling, spasms, etc.), memory loss, confusion or brain fog, short attention and concentration span, loss of libido or erectile dysfunction, altered menstrual cycle, urinary symptoms (infections, overactive bladder), hair loss, and other symptoms that can be considered residual [73,74].

- -

- Cognitive variables:

- (a)

- To assess the presence of cognitive impairment, the official Spanish version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [75,76,77] will be used, which is a test with adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’ alpha of 0.76) that assesses six cognitive domains (memory; visuospatial ability; executive function; attention, concentration or working memory; language; and temporo-spatial orientation). It is out of a total score of 30 points, and a correction of one point can be made in the case of subjects with fewer than 12 years of schooling. The cut-off point for the detection of mild cognitive impairment in its original version is 26. This test has been used to assess cognitive impairment of people with long COVID-19 [78,79].

- (b)

- The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SMDT) will also be used to detect dysfunction related to divided attention, visual tracking, perceptual, and motor speed and memory, both in children and adults, and with a test-retest reliability of between 0.84 and 0.93 in a sample of healthy adults. It consists of converting a series of 120 symbols of different shapes into the numbers that correspond to each one following the key provided. This must be conducted consecutively and as quickly as possible within 90 s after completing a 10-digit practical test. The total score is obtained by counting the number of correct substitutions completed out of a maximum score of 110. A score below 33 is considered a clear indicator of some type of cognitive disorder [80,81].

- (c)

- To measure short-term memory impairment, the Spanish version of the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS) will be used. This brief test assesses the existence of memory disorders using free recall (without clues) or selective recall (with semantic clues) of four words. In dementia screening, it presents adequate interobserver (0.85) and test–retest (0.81) reliability. Two points are awarded per word obtained by free recall and one point per word recalled with the help of semantic clues. The total scores range from zero to eight, with a score of four or less indicating possible cognitive impairment [82,83].

- (d)

- To assess whether verbal fluency is affected, the Semantic Verbal Fluency Test (Animals) (test-retest reliability of 0.68) will be used, which consists of counting the number of correct words reproduced in 1 min within the category ‘Animals’. Normally, a person without impairment will be able to reproduce about 16 words in 1 min [84,85].

- -

- Functional physical variables:

- (a)

- Cardiorespiratory capacity will be measured by a 6 min walk test (6MWT) [86]. It is a functional cardiorespiratory test that measures the maximum distance a subject can walk for 6 min. The test measures and records baseline and post-test heart rate, oxygen saturation (SpO2), and dyspnea according to the Borg scale [87]. The 6MWT walk had good test-retest reliability (88 < R < 94). We will use the most recent official Spanish version [88].

- (b)

- Leg strength and endurance will be measured by Sit to Stand Test [89]. We will use 30-s Sit to Stand Tests, which are used specifically to test for respiratory diseases [90]. The test evaluates endurance at a high power, speed, or velocity in terms of muscular or strength endurance by recording the number of times a person can stand up and sit down completely in the space of 30 s. The 30-s chair stand has good test-retest reliability (84 < R < 92). We will use the 30 s Sit to Stand Test that has been translated in Spanish and used for COVID-19 patients [91].

- -

- Affective state through the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire [92]. The HADS is a scale based on self-report that was developed to detect depression and anxiety disorders in medical patients in primary care settings. The HADS includes 14 items that assess symptoms of anxiety and depression (HADS-A and HADS-D, respectively), with each item corresponding to a 4-point (zero to three) scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 21 for symptoms of both anxiety and depression, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The HADS has been translated into a number of languages, including Spanish [93], to facilitate its use in international trials [94].

- -

- Sleep quality through the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). The ISI [95] works through self-reporting and measures a patient’s perception of nocturnal and diurnal symptoms of insomnia: difficulties initiating sleep, staying asleep, early morning awakening, satisfaction with current sleep pattern, interference with daily functioning, noticeability of impairment attributed to sleep deprivation, and degree of distress or concern caused by sleep deprivation. This scale has seven items, with each answer ranging from zero to four, and an overall score ranging from 0 to 28, with a higher score indicating a higher severity of insomnia. The Spanish version of the ISI [96] shows an adequate internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.82). It has also been used in other studies of people with long COVID-19 [97].

- -

- Physical activity will be measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) [103]. It assesses the levels of habitual physical activity over the preceding seven days. It has seven items and records activity at four levels of intensity: vigorous-intensity activity and moderate-intensity activity (walking and sitting). We will use the official Spanish version [104]. IPAQ-SF has sufficient validity for the measurement of total and vigorous physical activity and poor validity for moderate activity and good reliability [105].

- -

- Adherence to a Mediterranean diet will be measured using the 14-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS), encouraging compliance to a Mediterranean diet [106]. It includes items on food consumption and intake habits. The total score ranges from 0 to 14, with a higher score indicating greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet [107].

- -

- Personal constructs. The personal factors relating to behaviour that will be collected are the following:

- (a)

- Self-efficacy will be measured using the Self-Efficacy Scale-12 [108]. The original scale consisted of 17 items that are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Woodruff and Cashman [109] obtained a factor structure, based on the original 17-item scale, that represented the three aspects underlying the scale, i.e., willingness to initiate behavior, `Initiative’, willingness to expend effort in completing the behavior, `Effort’, and persistence in the face of adversity, `Persistence’. Five items were excluded because of low item-rest correlations and ambiguous wording, resulting in a 12-item version of the scale (GSES-12). This scale has 3 factors: Initiative (willingness to initiate behavior), Effort (willingness to make an effort to complete the behavior), and Persistence (persevering to complete the task in the face of adversity). Internal consistency of the original scale was 0.64 for initiative, 0.63 for effort, and 0.64 for persistence. The total scale obtained a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.69 [110].

- (b)

- Patient activation in their own health will be measured using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) questionnaire with regard to the management of their health [111]. It evaluates the patient’s perceived knowledge, skills, and confidence to engage in self-management activities through 13 items with a Likert Scale from one (strongly disagree) to four (strongly agree). The resulting score ranges between 13 and 52. Higher scores indicate higher levels of activation. There is only an official Spanish version for chronically ill patients. It has an item separation index for the parameters of 6.64 and a reliability of 0.98 [112].

- (c)

- Health literacy will be measured using the Health Literacy Europe Questionnaire (HLS-EUQ16) [113]. Health literacy is defined as the knowledge of the population, their motivation, and their individual ability to understand and make decisions related to the promotion and maintenance of their health. The questionnaire consists of 16 items, scored between 1 (very easy) and 4 (very difficult). The score of each subject was obtained as the sum of the scores of the 16 items. The final score can be transformed into a dichotomous response: very difficult and difficult = 0, as well as easy and very easy = 1. Higher scores indicate worse health literacy. It presents a high consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.982) in the official Spanish version [114].

- -

- For the analysis of the cost-efficiency, the Client Service Receipt Inventory will be used [115], collecting information on the entire range of services and support used by study participants. It retrospectively collects data on the use of services over the preceding six months (e.g., rates of use of individual services, mean intensity of service use, rates of accommodation use over time). We will use the official Spanish version [116].

2.2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pollard, C.A.; Morran, M.P.; Nestor-Kalinoski, A.L. The COVID-19 pandemic: A global health crisis. Physiol. Genom. 2020, 52, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salisbury, H. Helen Salisbury: When will we be well again? BMJ 2020, 369, m2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwan, N.A. Track COVID-19 sickness, not just positive tests and deaths. Nature 2020, 584, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwan, N.A. A negative COVID-19 test does not mean recovery. Nature 2020, 584, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldofsky, H.; Patcai, J. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post-SARS syndrome; a case-controlled study. BMC Neurol. 2011, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Troyer, E.A.; Kohn, J.N.; Hong, S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varatharaj, A.; Thomas, N.; Ellul, M.A.; Davies, N.W.; Pollak, T.A.; Tenorio, E.L.; Sultan, M.; Easton, A.; Breen, G.; Zandi, M.; et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: A UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, G.; Davis, H.; McCorkell, L. Report: What Does COVID-19 Recovery Actually Look Like?—Patient Led Research Collaborative. 2020. Available online: https://patientresearchcovid19.com/research/report-1/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- WHO. A Clinical Case Definition of Post COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Carfì, A.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F. Persistent Symptoms in Patients after Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E. Long term respiratory complications of COVID-19. BMJ 2020, 370, m3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, M.A.; Benjamin, L.; Singh, B.; Lant, S.; Michael, B.D.; Easton, A.; Kneen, R.; Defres, S.; Sejvar, J.; Solomon, T. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 767–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, T. Facing up to long COVID. Lancet 2020, 396, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhmerov, A.; Marbán, E. COVID-19 and the Heart. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abdelhafiz, A.S.; Ali, A.; Maaly, A.M.; Mahgoub, M.A.; Ziady, H.H.; Sultan, E.A. Predictors of post-COVID symptoms in Egyptian patients: Drugs used in COVID-19 treatment are incriminated. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivan, M.; Taylor, S. NICE guideline on long covid. BMJ 2020, 371, m4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Knight, M.; A’Court, C.; Buxton, M.; Husain, L. Management of post-acute COVID-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020, 370, m3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Green Paper on Citizen Science. Citizen Science for Europe towards a Better Society of Empowered Citizens and Enhanced Research; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, J.; Higgins, T.J.; Woodall, J.; White, S.M. Can social prescribing provide the missing link? Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2008, 9, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benedé Azagra, C.B.; Magallón Botaya, R.; Martín Melgarejo, T.; del-Pino-Casado, R.; Vidal Sánchez, M.I. What are we doing and what could we do from the health system in community health? SESPAS Report 2018. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedé Azagra, C.B.; Paz, M.S.; Sepúlveda, J. La orientación comunitaria de nuestra práctica: Hacer y no hacer (Community orientation of our practice: Do and do not do). Aten. Primaria 2018, 50, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, S.; Torres, E.; Ramos, M.; Ripoll, J.; García, A.; Bulilete, O.; Medina, D.; Vidal, C.; Cabeza, E.; Llull, M.; et al. Adult community health-promoting interventions in primary health care: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015, 76, S94–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botello, B.; Palacio, S.; García, M.; Margolles, M.; Fernandez, F.; Hernán, M.; Nieto, J.; Cofino, R. Methodology for health assets mapping in a community. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cofiño, R.; Aviñó, D.; Benedé, C.B.; Botello, B.; Cubillo, J.; Morgan, A.; Paredes-Carbonell, J.J.; Hernán, M. Health promotion based on assets: How to work with this perspective in local interventions? Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbunge, E.; Batani, J.; Gaobotse, G.; Muchemwa, B. Virtual healthcare services and digital health technologies deployed during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in South Africa: A systematic review. Glob. Health J. 2022, 6, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimarlund, V.; Koch, S.; Nøhr, C. Advances in E-Health. Life 2021, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, E.J. Evolutions in Telemedicine: From Smoke Signals to Mobile Health Solutions. J. Hosp. Libr. 2016, 16, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano de la Cuerda, R.; Muñoz Hellín, E.; Alguacil Diego, I.; Molina Rueda, F. Telerrehabilitation and neurology. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 51, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bäcker, H.C.; Wu, C.H.; Schulz, M.R.G.; Weber-Spickschen, T.S.; Perka, C.; Hardt, S. App-based rehabilitation program after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2021, 141, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.R.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.C.; Kim, H.R.; Song, S.; Kwon, H.; Ji, W.; Choi, C.M. Mobile Phone App–Based Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Chemotherapy-Treated Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer: Pilot Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ji, W.; Kwon, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Hong, J.S.; Park, Y.R.; Kim, H.R.; Lee, J.C.; Jung, E.J.; Kim, D.; et al. Mobile Health Management Platform–Based Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Patients with Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Prospective Clinical Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira AG da, S.; Pinto, A.C.P.N.; Garcia, B.M.S.P.; Eid, R.A.C.; Mól, C.G.; Nawa, R.K. Telerehabilitation improves physical function and reduces dyspnoea in people with COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 conditions: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2022, 68, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbosco-Salas, M.; Torres-Castro, R.; Leyton, A.R.; Zapata, F.M.; Salazar, E.H.; Bastías, G.E.; Díaz, M.E.B.; Allers, K.T.; Fonseca, D.M.; Vilaró, J. Effectiveness of a Primary Care Telerehabilitation Program for Post-COVID-19 Patients: A Feasibility Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Baker, S.C.; Baric, R.S.; de Groot, R.J.; Drosten, C.; Gulyaeva, A.A.; Haagmans, B.L.; Lauber, C.; Leontovich, A.M.; Neuman, B.W.; et al. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, R.M.M.; Ghonimy, M.B.I. Post-COVID-19 pneumonia lung fibrosis: A worrisome sequelae in surviving patients. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2021, 52, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, H.; Stucki, G.; Bickenbach, J. COVID-19 and Post Intensive Care Syndrome: A Call for Action. J. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 52, jrm00044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchner, B.; Sahanic, S.; Kirchmair, R.; Pizzini, A.; Sonnweber, B.; Wöll, E.; Mühlbacher, A.; Garimorth, K.; Dareb, B.; Ehling, R.; et al. Beneficial effects of multi-disciplinary rehabilitation in post-acute COVID-19-an observational cohort study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torjesen, I. NICE backtracks on graded exercise therapy and CBT in draft revision to CFS guidance. BMJ 2020, 371, m4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, S.B.; Shah, A.J.; Saigal, A.; Smith, C.; Brill, S.E.; Goldring, J.; Hurst, J.R.; Jarvis, H.; Lipman, M.; Mandal, S. The high mental health burden of “Long COVID” and its association with on-going physical and respiratory symptoms in all adults discharged from hospital. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2004364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titze-De-Almeida, R.; da Cunha, T.R.; Silva, L.D.d.S.; Ferreira, C.S.; Silva, C.P.; Ribeiro, A.P.; Júnior, A.d.C.M.S.; Brandão, P.R.D.P.; Silva, A.P.B.; da Rocha, M.C.O.; et al. Persistent, new-onset symptoms and mental health complaints in Long COVID in a Brazilian cohort of non-hospitalized patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, M.; Backhaus, L.; Azevedo, P.M.; Hügle, T. An mHealth App for Fibromyalgia-like Post–COVID-19 Syndrome: Protocol for the Analysis of User Experience and Clinical Data. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e32193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; Goodfellow, H.; Bindman, J.; Blandford, A.; Bradbury, K.; Chaudhry, T.; Fernandez-Reyes, D.; Gomes, M.; Hamilton, F.L.; Heightman, M.; et al. Development, deployment and evaluation of digitally enabled, remote, supported rehabilitation for people with long COVID-19 (Living With COVID-19 Recovery): Protocol for a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, G.O.; Pacione, C.; Shultz, R.K.; Klügl, M. Leveraging Human-Centered Design in Chronic Disease Prevention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 48, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomin, J. What Is Human Centred Design? Des. J. 2014, 17, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torrente, G.; de Souza, T.Q.; Tonaki, L.; Cardoso, A.P.; Junior, L.M.; da Silva, G.O. Scrum Framework and Health Solutions: Management and Results. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2021, 284, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stare, A. Agile project management—A future approach to the management of projects? Dyn. Relatsh. Manag. J. 2013, 2, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, P. NICE guideline on long COVID. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Gómez, F. Guía Clínica Para Atención de COVID Persistente; Sociedad Española de Médicos Generales y de Familia (SEMG): Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Confederation for Physical Therapy. Respuesta de la World Physiotherapy al COVID-19; World Physiotherapy: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Support for Rehabilitation after COVID-19—Related Illness; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jimeno-Almazán, A.; Pallarés, J.G.; Buendía-Romero, Á.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Franco-López, F.; Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B.J.; Bernal-Morel, E.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome and the Potential Benefits of Exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Hoang, A. Nutrition therapy for long COVID. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, S28–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, E. Coronavirus Disease 19 from the Perspective of Ageing with Focus on Nutritional Status and Nutrition Management—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepsomali, P.; Groeger, J. Diet, Sleep, and Mental Health: Insights from the UK Biobank Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill Almeida, L.M.; Flicker, L.; Hankey, G.J.; Golledge, J.; Yeap, B.B.; Almeida, O.P. Disrupted sleep and risk of depression in later life: A prospective cohort study with extended follow up and a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 309, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish, L.A.; Kline, C.E.; Gunn, H.E.; Buysse, D.J.; Hall, M.H. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 22, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Young, P. Schlafstörungen und Erschöpfungssyndrom bei Long-COVID-Syndrom: Fallbasierte Erfahrungen aus der neurologischen/schlafmedizinischen Rehabilitation. Somnologie 2022, 26, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekhael, M.; Lim, C.H.; El Hajjar, A.H.; Noujaim, C.; Pottle, C.; Makan, N.; Dagher, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chouman, N.; Li, D.L.; et al. Studying the Effect of Long COVID-19 Infection on Sleep Quality Using Wearable Health Devices: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e38000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19; NICE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Altuna, M.; Sánchez-Saudinós, M.; Lleó, A. Cognitive symptoms after COVID-19. Neurol. Perspect. 2021, 1, S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maiman, L.A.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: Origins and Correlates in Psychological Theory. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model and Sick Role Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J.; Hechhausen, H. Motivation and Action, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.; Ferrer, M.; Vilagut, G.; Broquetas, J.M.; Roca, J.; Batlle, J.S.; Antó, J.M. Testing the Measurement Properties of the Spanish Version of the SF-36 Health Survey Among Male Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.; Antó, J.M. The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey (the SF-36 health questionnaire): An instrument for measuring clinical results. Med. Clin. 1995, 104, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Colón, H.; Haertlein, C. Spanish Translation of the Role Checklist. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2002, 56, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, P.J.; McKinney, K.G.; Perron, J.M.; Ruff, E.G.; Smiley, J.L. The Revised Role Checklist: Improved Utility, Feasibility, and Reliability. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2018, 39, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley, F.; Kielhofner, G.; Barris, R.; Reichler, R.K. The Role Checklist: Development and Empirical Assessment of Reliability. Occup. Ther. J. Res. 1986, 6, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwatanakul, K.; Kelvie, W.; Lasagna, L.; Calimlim, J.F.; Weis, O.F.; Mehta, G. Studies with different types of visual analog scales for measurement of pain. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1983, 34, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaes, A.W.; Machado, F.V.; Meys, R.; Delbressine, J.M.; Goertz, Y.M.; Van Herck, M.; Houben-Wilke, S.; Franssen, F.M.; Vijlbrief, H.; Spies, Y.; et al. Care Dependency in Non-Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Service (NHS). Long-Term Effects of Coronavirus (Long COVID); NHS: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Moreno, S.; Cuadrado, M.; Cruz-Orduña, I.; Martínez-Acebes, E.; Gordo-Mañas, R.; Fernández-Pérez, C.; García-Ramos, R. Validation of the Spanish-language version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment as a screening test for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Neurología 2022, 37, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, M.L.; Ferrándiz, M.H.; Garriga, O.T.; Nierga, I.P.; López-Pousa, S.; Franch, J.V. Validación del Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Test de cribado para el deterioro cognitivo leve. Alzheimer Real. Investig. Demenc. 2009, 43, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cristillo, V.; Pilotto, A.; Piccinelli, S.C.; Bonzi, G.; Canale, A.; Gipponi, S.; Bezzi, M.; Leonardi, M.; Padovani, A.; Libri, I.; et al. Premorbid vulnerability and disease severity impact on Long-COVID cognitive impairment. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressing, A.; Bormann, T.; Blazhenets, G.; Schroeter, N.; Walter, L.I.; Thurow, J.; August, D.; Hilger, H.; Stete, K.; Gerstacker, K.; et al. Neuropsychologic Profiles and Cerebral Glucose Metabolism in Neurocognitive Long COVID Syndrome. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 63, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Galarza, C.; Acosta-Rodas, P.; Jadán-Guerrero, J.; Guevara-Maldonado, C.B.; Zapata-Rodríguez, M.; Apolo-Buenaño, D. Evaluación Neuropsicológica de la Atención: Test de Símbolos y Dígitos. Rev. Ecuat. Neurol. 2018, 27, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Arango-Lasprilla, J.; Rivera, D.; Rodríguez, G.; Garza, M.; Galarza-Del-Angel, J.; Velázquez-Cardoso, J.; Aguayo, A.; Schebela, S.; Weil, C.; Longoni, M.; et al. Symbol Digit Modalities Test: Normative data for the Latin American Spanish speaking adult population. NeuroRehabilitation 2015, 37, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pérez Martínez, D.A.; Baztán, J.J.; González Becerra, M.; Socorro, A. Evaluación de la utilidad diagnóstica de una adaptación española del Memory Impairment Screen de Buschke para detectar demencia y deterioro cognitivo. Rev. Neurol. 2005, 40, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, P.; Peña-Casanova, J.; Gramunt, N.; Manero, R.M.; Terrón, C.; Quiñones Úbeda, S. Versión Española del Memory Impairment Screen (MIS): Datos normatives y de validez discriminativa. Neurologia 2005, 20, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ardila, A.; Ostrosky-Solís, F.; Bernal, B. Cognitive testing toward the future: The example of Semantic Verbal Fluency (ANIMALS). Int. J. Psychol. 2006, 41, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.E.; Buxton, P.; Husain, M.; Wise, R. Short test of semantic and phonological fluency: Normal performance, validity and test-retest reliability. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 39, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butland, R.J.; Pang, J.; Gross, E.R.; Woodcock, A.A.; Geddes, D.M. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br. Med. J. 1982, 284, 1607–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mangado, N.; Rodríguez-Nieto, M.J. Prueba de la marcha de los 6 minutos. Med. Respir. 2016, 9, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Csuka, M.; McCarty, D.J. Simple method for measurement of lower extremity muscle strength. Am. J. Med. 1985, 78, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, A.; Aiello, M.; Cherubino, F.; Zampogna, E.; Chetta, A.; Azzola, A.; Spanevello, A. The one repetition maximum test and the sit-to-stand test in the assessment of a specific pulmonary rehabilitation program on peripheral muscle strength in COPD patients. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Gerez, J.J.; Bernal-Utrera, C.; Anarte-Lazo, E.; Garcia-Vidal, J.A.; Botella-Rico, J.M.; Rodriguez-Blanco, C. Therapeutic pulmonary telerehabilitation protocol for patients affected by COVID-19, confined to their homes: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tejero, A.; Guimerá, E.; Farré, J.; Peri, J. Uso clíınico del HAD (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) en población psiquiátrica: Un estudio de su sensibilidad, fiabilidad y validez. Rev. Dep. Psiquiatr. Fac. Med. Barc. 1986, 13, 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, C.; Worrall-Davies, A.; McMillan, D.; Gilbody, S.; House, A. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: A diagnostic meta-analysis of case-finding ability. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, A.; Vela-Bueno, A.; Olavarrieta-Bernardino, S.; Calhoun, S.L.; Bixler, E.O.; Vgontzas, A.N. The Spanish version of the Insomnia Severity Index: A confirmatory factor analysis. Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrù, G.; Bertelloni, D.; Diolaiuti, F.; Mucci, F.; Di Giuseppe, M.; Biella, M.; Gemignani, A.; Ciacchini, R.; Conversano, C. Long-COVID Syndrome? A Study on the Persistence of Neurological, Psychological and Physiological Symptoms. Healthcare 2021, 9, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, L.; Luna, J.; Bailón, E.; Medina, I. Validation of the MOS questionnaire of social support in Primary Care. Med. Fam. 2005, 10, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- García, E.; Herrero, J.; Musitu, G. Evaluación de Recursos y Estresores Psicosociales en la Comunidad; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, J.; Gracia, E. Measuring perceived community support: Factorial structure, longitudinal invariance, and predictive validity of the PCSQ (perceived community support questionnaire). J. Community Psychol. 2007, 35, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J.; Gracia, E. Predicting social integration in the community among college students. J. Community Psychol. 2004, 32, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, I.; Kang, M. Convergent validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): Meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 16, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Román Viñas, B.; Ribas Barba, L.; Ngo, J.; Serra Majem, L. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire in the Catalan population (Spain). Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kurtze, N.; Rangul, V.; Hustvedt, B.-E. Reliability and validity of the international physical activity questionnaire in the Nord-Trøndelag health study (HUNT) population of men. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Covas, M.I.; Fiol, M.; Wärnberg, J.; Arós, F.; Ruíz-Gutiérrez, V.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; et al. Cohort Profile: Design and methods of the PREDIMED study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A Short Screener Is Valid for Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence among Older Spanish Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherer, M.; Maddux, J.E.; Mercandante, B.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Jacobs, B.; Rogers, R.W. The Self-Efficacy Scale: Construction and Validation. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 51, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, S.L.; Cashman, J.F. Task, Domain, and General Efficacy: A Reexamination of the Self-Efficacy Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1993, 72, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosscher, R.J.; Smit, J.H. Confirmatory factor analysis of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Behav. Res. Ther. 1998, 36, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno Chico, C.; González de Paz, L.; Monforte Royo, C. Adaptación y Validación de la Escala (PAM13), Evaluación de la Activación “Patient Activation Measure 13”, en una Muestra de Pacientes Crónicos Visitados en CAP Rambla Mútua Terrassa; XXIV Premi d’infermeria; Mútua Terrassa: Terrassa, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nolasco, A.; Barona, C.; Tamayo-Fonseca, N.; Irles, M.Á.; Más, R.; Tuells, J.; Pereyra-Zamora, P. Health literacy: Psychometric behaviour of the HLS-EU-Q16 questionnaire. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 34, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, M. Economic Evaluation of Mental Health Care. In Contemporary Psychiatry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Barquero, L.; Gaite, J.; Cuesta, L.; Usieto, E.; Knapp, M.; Beecham, J. Spanish version of the CSRI: A mental health cost evaluation interview. Arch. Neurobiol. 1997, 60, 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.C.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2010, 1, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Hout, B.A.; Al, M.J.; Gordon, G.S.; Rutten, F.F. Costs, effects and C/E-ratios alongside a clinical trial. Health Econ. 1994, 3, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Sanchiz, P.; Nogueira-Arjona, R.; García-Ruiz, A.; Luciano, J.V.; García Campayo, J.; Gili, M.; Botella, C.; Baños, R.; Castro, A.; López-Del-Hoyo, Y.; et al. Economic evaluation of a guided and unguided internet-based CBT intervention for major depression: Results from a multicenter, three-armed randomized controlled trial conducted in primary care. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblikue Consulting. Oblikue Database; Oblikue Consulting S.L.: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alonso, J.; Regidor, E.; Barrio, G.; Prieto, L.; Rodríguez, C.; De La Fuente, L. Population reference values of the Spanish version of the Health Questionnaire SF-36. Med. Clín. 1998, 111, 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia Fuster Enrique Herrero Olaizola, J.; Musitu Ochoa, G. Evaluación de Recursos y Estresores Psicosociales en la Comunidad. Inf. Psicol. 2002, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, H. Helen Salisbury: Living under the long shadow of covid. BMJ 2022, 377, o1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Behaviour Change: Individual Approaches. NICE Public Health Guidance 49 (PH49). 2014. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/ph49 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Cox, N.S.; Dal Corso, S.; Hansen, H.; McDonald, C.F.; Hill, C.J.; Zanaboni, P.; Alison, J.A.; O’Halloran, P.; Macdonald, H.; Holland, A.E. Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taito, S.; Yamauchi, K.; Kataoka, Y. Telerehabilitation in Subjects with Respiratory Disease: A Scoping Review. Respir. Care 2021, 66, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, N.S.; McDonald, C.F.; Mahal, A.; Alison, J.A.; Wootton, R.; Hill, C.J.; Zanaboni, P.; O’Halloran, P.; Bondarenko, J.; Macdonald, H.; et al. Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease: A randomised controlled equivalence trial. Thorax 2021, 77, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gerez, J.; Saavedra-Hernandez, M.; Anarte-Lazo, E.; Bernal-Utrera, C.; Perez-Ale, M.; Rodriguez-Blanco, C. Short-Term Effects of a Respiratory Telerehabilitation Program in Confined COVID-19 Patients in the Acute Phase: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Respiratory rehabilitation in elderly patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suso-Martí, L.; La Touche, R.; Herranz-Gómez, A.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Cuenca-Martínez, F. Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation in Physical Therapist Practice: An Umbrella and Mapping Review with Meta–Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambi, G.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Alrawaili, S.M.; Elsayed, S.H.; Verma, A.; Vellaiyan, A.; Eid, M.M.; Aldhafian, O.R.; Nwihadh, N.B.; Saleh, A.K. Comparative effectiveness study of low versus high-intensity aerobic training with resistance training in community-dwelling older men with post-COVID 19 sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abodonya, A.M.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Awad, E.A.; Elalfy, I.E.; Salem, H.A.; Elsayed, S.H. Inspiratory muscle training for recovered COVID-19 patients after weaning from mechanical ventilation. Medicine 2021, 100, e25339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, S.M.; Rosenfeldt, A.B.; Bay, R.C.; Sahu, K.; Wolf, S.L.; Alberts, J.L. Improving Quality of Life and Depression after Stroke Through Telerehabilitation. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 6902290020p1–6902290020p10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeong, I.; Karpatkin, H.; Finkelstein, J. Physical Telerehabilitation Improves Quality of Life in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. In Nurses and Midwives in the Digital Age; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciante, L.; Pieta, C.D.; Rutkowski, S.; Cieślik, B.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J.; Agostini, M.; Kiper, P. Cognitive telerehabilitation in neurological patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 847–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, P.; Bernetti, A.; Fiore, P.; Bargellesi, S.; Bonaiuti, D.; Brianti, R.; Calvaruso, S.; Checchia, G.A.; Costa, M.; Galeri, S.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on rehabilitation services and Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine physicians’ activities in Italy an official document of the Italian PRM Society (SIMFER). Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 56, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Instruments | Assessment Areas |

|---|---|

| Gender, ages, civil status, education, household, occupation. Role Checklist [71] | Socio-demographic variables |

| Clinical history, contraction of COVID-19, timeline of developing Long COVID, number of residual symptoms and their severity (EVA), days taken on sick-leave [73,74] | Clinical variables |

| SF-36 [68,124] | Quality of life |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment [75,76,77] The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SMDT) [80,81] Memory Impairment Screen (MIS) [82,83] Semantic Verbal Fluency Test (Animals) [84,85] | Cognitive variables |

| 6 min walk test (6MWT) [86] Sit to Stand Test 30 sg [89] | Functional physical variables |

| HADS [92] | Affective state |

| Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [95] | Sleep Quality |

| Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SS) [98] Perceived Community Support Questionnaire [125] | Social Support |

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) [103] | Physical Activity |

| 14-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS) [106] | Adherence to a Mediterranean diet |

| Self-Efficacy Scale [108] Patient Activation Measure Questionnaire (PAM) [111] Health Literacy Europe Questionnaire (HLS-EUQ16) [113] | Personal constructs |

| Client Service Receipt Inventory [115] | Social and health services used |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samper-Pardo, M.; León-Herrera, S.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Benedé-Azagra, B.; Magallón-Botaya, R.; Gómez-Soria, I.; Calatayud, E.; Aguilar-Latorre, A.; Méndez-López, F.; Pérez-Palomares, S.; et al. Development and Validation of a Mobile Application as an Adjuvant Treatment for People Diagnosed with Long COVID-19: Protocol for a Co-Creation Study of a Health Asset and an Analysis of Its Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010462

Samper-Pardo M, León-Herrera S, Oliván-Blázquez B, Benedé-Azagra B, Magallón-Botaya R, Gómez-Soria I, Calatayud E, Aguilar-Latorre A, Méndez-López F, Pérez-Palomares S, et al. Development and Validation of a Mobile Application as an Adjuvant Treatment for People Diagnosed with Long COVID-19: Protocol for a Co-Creation Study of a Health Asset and an Analysis of Its Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010462

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamper-Pardo, Mario, Sandra León-Herrera, Bárbara Oliván-Blázquez, Belén Benedé-Azagra, Rosa Magallón-Botaya, Isabel Gómez-Soria, Estela Calatayud, Alejandra Aguilar-Latorre, Fátima Méndez-López, Sara Pérez-Palomares, and et al. 2023. "Development and Validation of a Mobile Application as an Adjuvant Treatment for People Diagnosed with Long COVID-19: Protocol for a Co-Creation Study of a Health Asset and an Analysis of Its Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010462

APA StyleSamper-Pardo, M., León-Herrera, S., Oliván-Blázquez, B., Benedé-Azagra, B., Magallón-Botaya, R., Gómez-Soria, I., Calatayud, E., Aguilar-Latorre, A., Méndez-López, F., Pérez-Palomares, S., Cobos-Rincón, A., Valero-Errazu, D., Sagarra-Romero, L., & Sánchez-Recio, R. (2023). Development and Validation of a Mobile Application as an Adjuvant Treatment for People Diagnosed with Long COVID-19: Protocol for a Co-Creation Study of a Health Asset and an Analysis of Its Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010462