Association between Motivation in Physical Education and Positive Body Image: Mediating and Moderating Effects of Physical Activity Habits

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Body Image, Physical Activity, and Physical Education

1.1.1. Body Image and Physical Activity

1.1.2. Body Image and Physical Education

1.2. Self-Determination Theory in Physical Education and Body Image

1.3. Physical Activity Habits as Mediators and Moderators between Autonomous Motivation for Physical Education and Positive Body Image

1.3.1. Physical Activity Habits and Autonomous Motivation

1.3.2. Physical Activity Habits as a Mediator between Physical Education Motivation and Positive Body Image

1.3.3. Physical Activity Habits as Moderators between Physical Education Motivation, Perceived Physical Fitness, and Positive Body Image

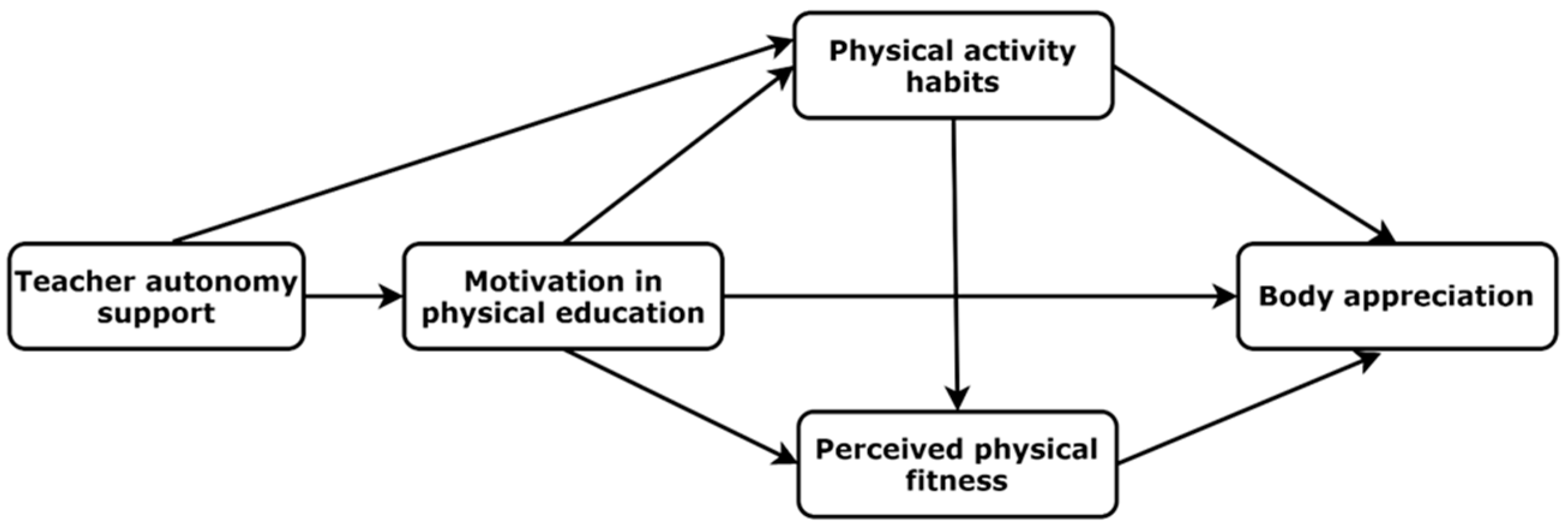

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants and Procedure

2.2. Study Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

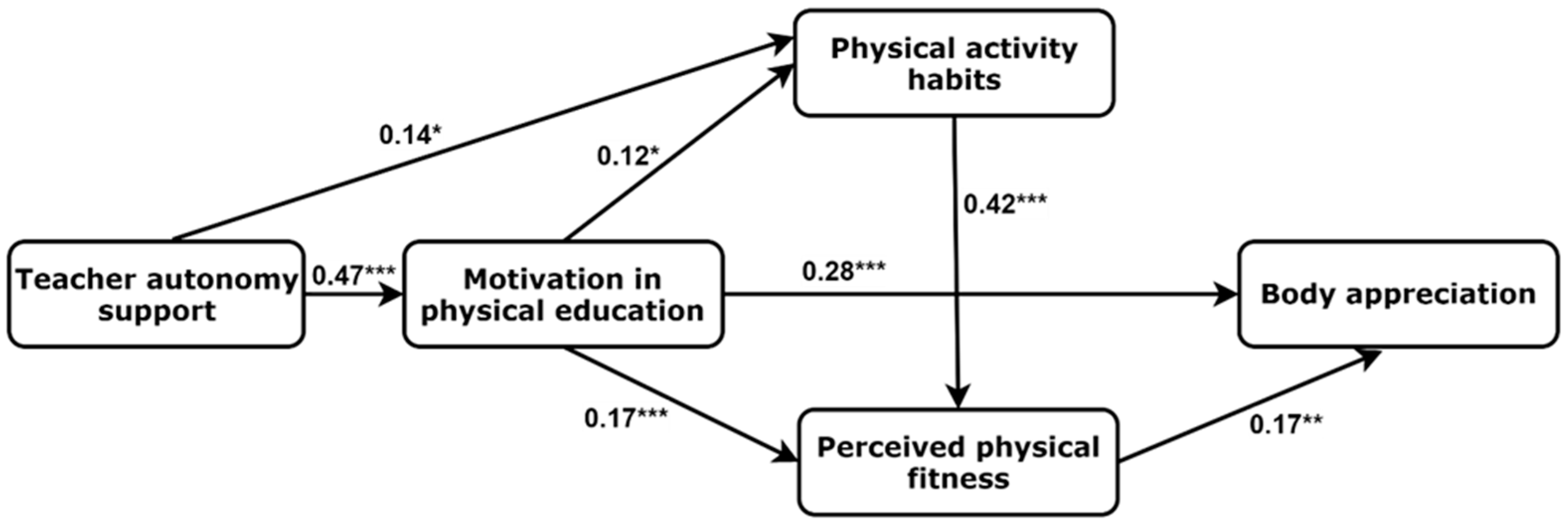

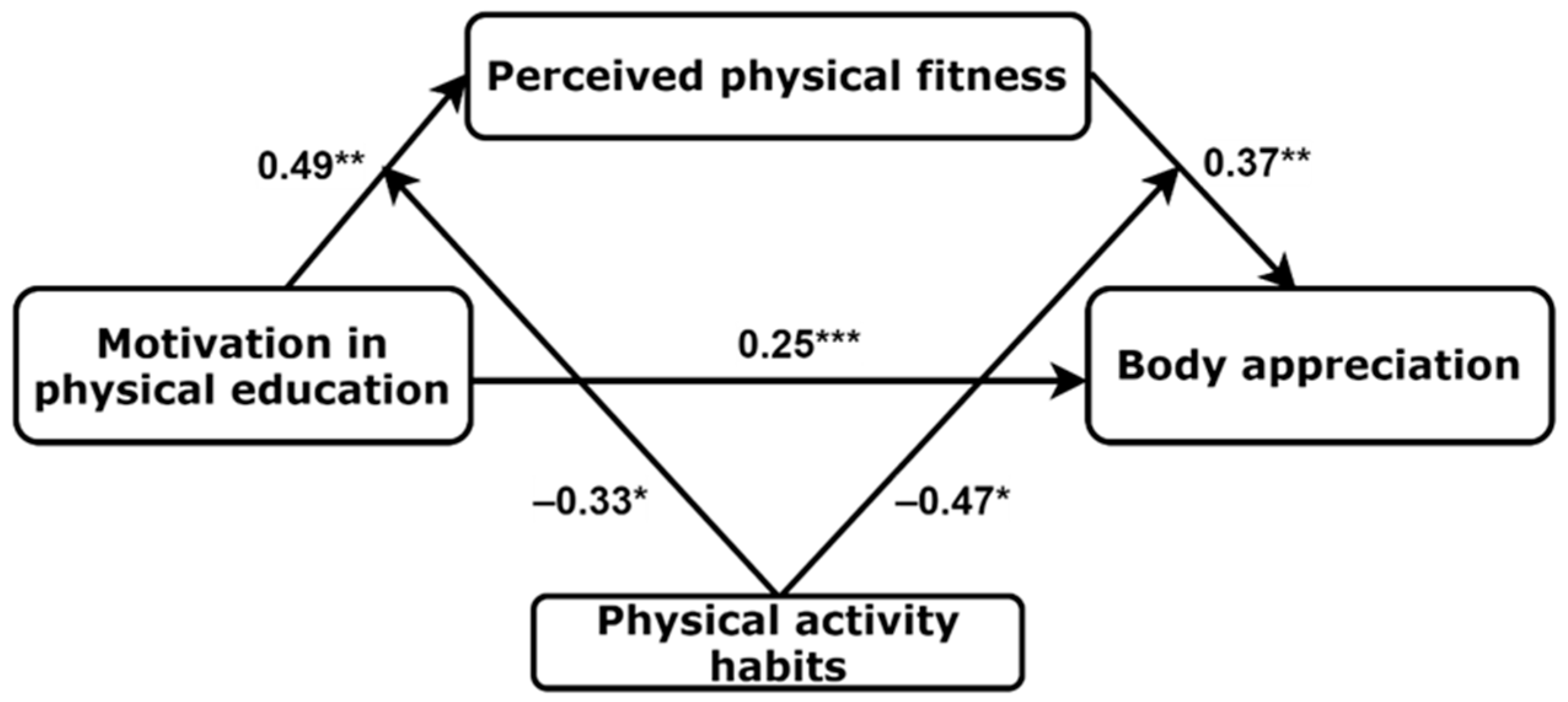

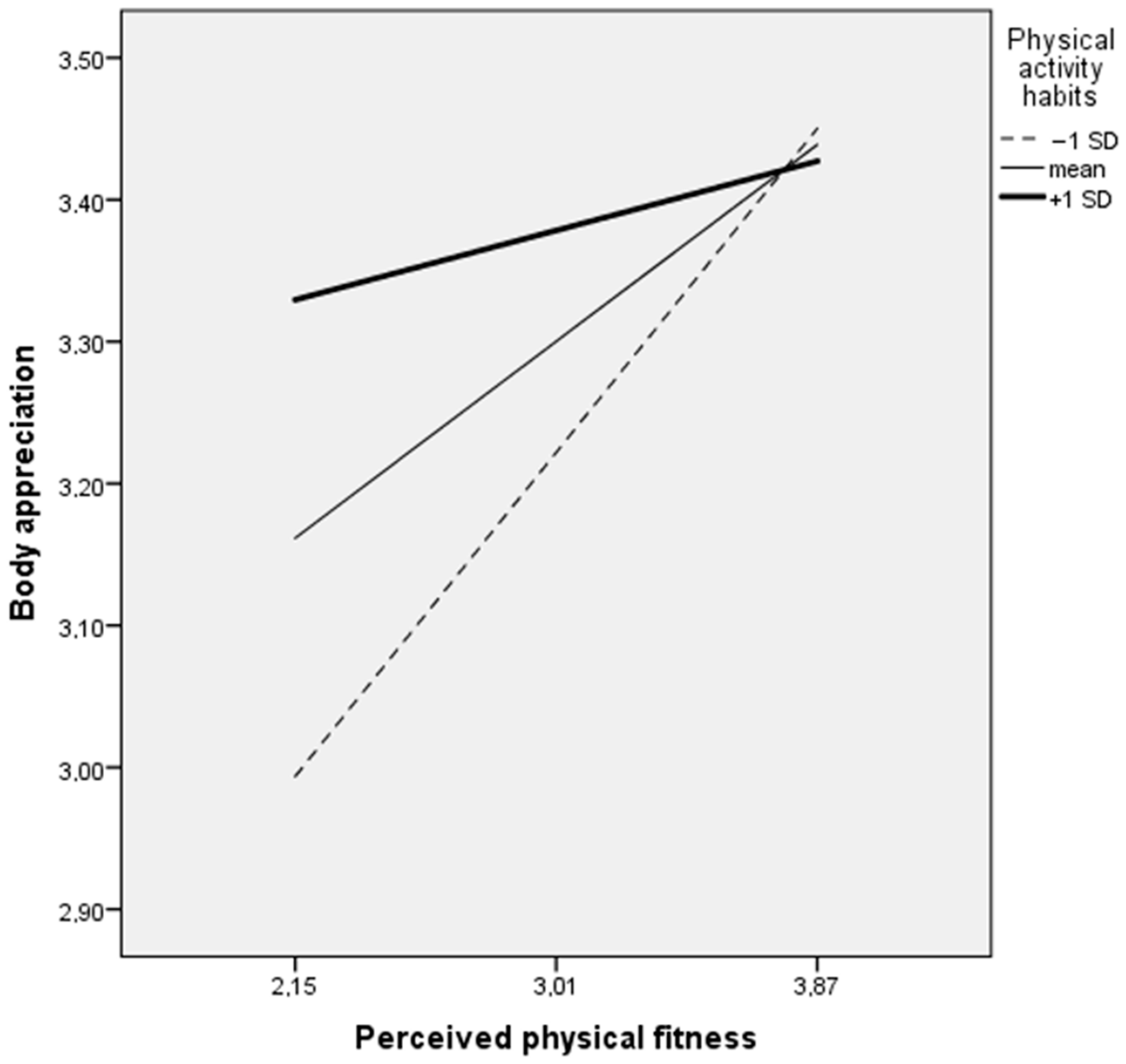

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Posadzki, P.; Pieper, D.; Pajpai, R.; Makaruk, H.; Konsgen, N.; Neuhaus, A.L.; Semwal, M. Exercise/physical activity and health outcomes: An overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Ciaccioni, S.; Thomas, G.; Vergeer, I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sluijs, E.M.; Ekelund, U.; Crochemore-Silva, I.; Guthold, R.; Ha, A.; Lubans, D.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Ding, D.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: Current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet 2021, 398, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Martin, A.; Janssen, X.; Wilson, M.G.; Gibson, A.M.; Hughes, A.; Reilly, J.J. Longitudinal changes in moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Rebullido, T.R.; MacDonald, J.P. Pediatric inactivity triad: A risky PIT. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quennerstedt, M. Physical education and the art of teaching: Transformative learning and teaching in physical education and sports pedagogy. Sport Educ. Soc. 2019, 24, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonstroem, R.J.; Harlow, L.L.; Josephs, L. Exercise and self-esteem: Validity of model expansion and exercise associations. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1994, 16, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, C.; Haerens, L.; Kirk, D. Understanding body image in physical education: Current knowledge and future directions. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 24, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røset, L.; Green, K.; Thurston, M. ‘Even if you don’t care…you do care after all’: ‘Othering’ and physical education in Norway. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 622–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiston, C.M.; Pila, E.; Vani, M.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Body image, physical activity, and sport: A scoping review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, C.; Kirk, D.; Meester, A.D.; Haerens, L. Why is physical education more stimulating for pupils who are more satisfied with their own body? Health Educ. J. 2019, 78, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodewyk, K.R.; Sullivan, P. Associations between anxiety, self-efficacy, and outcomes by gender and body size dissatisfaction during fitness in high school physical education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, C.; Prescott, A.; Smith, R.; Owen, M. A systematic review exploring body image programmes and interventions in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 942–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, D.; Ingledew, D.K. The relationships between body mass and body image and relative autonomy for exercise among adolescent males and females. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panão, I.; Carraça, E.V. Effects of exercise motivations on body image and eating habits/behaviours: A systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.; Wertheim, E.H. Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice; Cash, T.F., Pruzinsky, T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 11, pp. 247–248. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Añez, E.; Fornieles-Deu, A.; Fauquet-Ars, J.; López-Guimerà, G.; Puntí-Vidal, J.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Body image dissatisfaction, physical activity and screen-time in Spanish adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 23, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, E.L.; Gaspar, M.E.; DiTore, R.; Piers, A.D.; Schaumberg, K. Conceptualizing body dissatisfaction in eating disorders within a self-discrepancy framework: A review of evidence. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2018, 23, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calogero, R.M.; Tylka, T.L.; McHilley, B.H.; Pedrotty-Stump, K.N. Attunement with exercise (AWE). In Handbook of Positive Body Image and Embodiment; Tylka, T.L., Piran, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N.L. What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image 2015, 14, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piran, N. Journeys of Embodiment at the Intersection of Body and Culture: The Developmental Theory of Embodiment; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alleva, J.M.; Tylka, T.L. Body functionality: A review of the literature. Body Image 2021, 36, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, J.E.; Krawczyk, R.; Thompson, J.K. Attitudinal Assessment of Body Image for Adolescents and Adults; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, E.; Costa, B.; Williamson, H.; Meyrick, J.; Halliwell, E.; Harcourt, D. The effectiveness of interventions aiming to promote positive body image in adults: A systematic review. Body Image 2019, 30, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- More, K.R.; Hayes, N.L.; Phillips, L.A. Contrasting constructs or continuum? Examining the dimensionality of body appreciation and body dissatisfaction. Psychol. Health 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; McClure, Z.; Tylka, T.L.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Body appreciation and its psychological correlates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image 2022, 42, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett-Gunter, R.; McEwan, D.; Kamarhie, A. Physical activity and body image among men and boys: A meta-analysis. Body Image 2017, 22, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano-García, D.; Infantes-Paniagua, Á.; Cuevas-Campos, R.; Fernández-Bustos, J.G. Impact of physical activity-based interventions on children and adolescents’ physical self-concept: A meta-analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Baceviciene, M. Testing modified gender-moderated exercise and self-esteem (EXSEM) model of positive body image in adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 27, 1805–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, B.D.; Barber, B.L. Differences in functional and aesthetic body image between sedentary girls and girls involved in sports and physical activity: Does sport type make a difference? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiston, C.M.; Doré, I.; Lucibello, K.M.; Pila, E.; Brunet, J.; Thibault, V.; Bélanger, M. Body image self-conscious emotions get worse throughout adolescence and relate to physical activity behavior in girls and boys. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 315, 115543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pila, E.; Sabiston, C.M.; Mack, D.E.; Wilson, P.M.; Brunet, J.; Kowalski, K.C.; Crocker, P.R. Fitness- and appearance-related self-conscious emotions and sport experiences: A prospective longitudinal investigation among adolescent girls. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 47, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.E.; Ullrich-French, S.; Madonia, J.; Witty, K. Social physique anxiety in physical education: Social contextual factors and links to motivation and behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsebø, A.K.S.; Løvoll, H.S.; Rune, J.K. Students’ perceptions of visibility in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, C.; Haerens, L.; Kirk, D. Body dissatisfaction, perceptions of competence, and lesson content in physical education. J. Sch. Health 2018, 88, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, K.; Sarkar, M.; Spray, C. Exploring common stressors in physical education: A qualitative study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, W.; Edwards, A.; Cudmore, L. Positioning Australia’s contemporary health and physical education curriculum to address poor physical activity participation rates by adolescent girls. Health Educ. J. 2016, 75, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.S.; Alter, Z.; Lee, R.M.; Gordon, A.R.; Cory, H.; Brion-Meisels, G.; Reiner, J.; Topping, K.; Kenney, E.L. “It’s not the stereotypical 80s movie bullying”: A qualitative study on the high school environment, body image, and weight stigma. J. Sch. Health 2022, 92, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, J.G.; McIntosh, I.; Kiely, J.; Collins, D.J. The post 16 gap: How do young people conceptualise PE? An exploration of the barriers to participation in physical education, physical activity and sport in senior school pupils. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2021, 33, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, D.; Parker, P.D.; Hilland, T.; Cinelli, R.; Owen, K.B.; Kapsal, N.; Lee, J.; Antczak, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; et al. Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1444–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Williams, G.C.; Patrick, H.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and physical activity: The dynamics of motivation in development and wellness. Hell. J. Psychol. 2009, 6, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Ntoumanis, N. The role of self-determined motivation in the understanding of exercise-related behaviours, cognitions and physical self-evaluations. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, M.J.; Eyre, E.L.J.; Bryant, E.; Seghers, J.; Galbraith, N.; Nevill, A.M. Autonomous motivation mediates the relation between goals for physical activity and physical activity behavior in adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dishman, R.K.; McIver, K.L.; Dowda, M.; Pate, R.R. Declining physical activity and motivation from middle school to high school. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Koka, A.; Hein, V.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L. Motivational processes in physical education and objectively measured physical activity among adolescents. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. A test of self-determination theory in school physical education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 75, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Barkoukis, V.; Liukkonen, J. Relationships among perceived motivational climate, motivational regulations, enjoyment, and PA participation among Finnish physical education students. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 15, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtiniemi, M.; Sääkslahti, A.; Tolvanen, A.; Watt, A.; Jaakkola, T. The relationships among motivational climate, perceived competence, physical performance, and affects during physical education fitness testing lessons. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, V.; Hagger, M.S. Global self-esteem, goal achievement orientations, and self-determined behavioural regulations in a physical education setting. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S. Habit and physical activity: Theoretical advances, practical implications, and agenda for future research. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Orbell, S. Reflections on past behavior: A self-report index of habit strength. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S. Redefining habits and linking habits with other implicit processes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 46, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radel, R.; Pelletier, L.; Pjevac, D. The links between self-determined motivations and behavioral automaticity in a variety of real-life behaviors. Motiv. Emot. 2017, 41, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D.T.; Wood, W.; Labrecque, J.S.; Lally, P. How do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of habits in daily life. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; Gardner, B. Promoting habit formation. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013, 7, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Lally, P. Does intrinsic motivation strengthen physical activity habit? Modeling relationships between self-determination, past behaviour, and habit strength. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 36, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Hein, V.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I.; Lintunen, T.; Leemans, S. Teacher, peer and parent autonomy support in physical education and leisure-time physical activity: A trans-contextual model of motivation in four nations. Psychol. Health 2009, 24, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.A. theory of planned behavior. Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, R.J. Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 29, 271–360. [Google Scholar]

- Barkoukis, V.; Chatzisarantis, N.; Hagger, M.S. Effects of a school-based intervention on motivation for out-of-school physical activity participation. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2021, 92, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Washington, T.; Yli-Piipari, S. The association between motivation in school physical education and self-reported physical activity during Finnish junior high school: A self-determination theory approach. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2013, 19, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C.; Deci, E.L. Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Urmanavicius, D.; Baceviciene, M. Associations between perceived teacher autonomy support, self-determined motivation, physical activity habits and non-participation in physical education in a sample of Lithuanian adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachopoulos, S.P.; Katartzi, E.S.; Kontou, M.G.; Moustaka, F.C.; Goudas, M. The revised perceived locus of causality in physical education scale: Psychometric evaluation among youth. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D.P.; Scott, S.; Van Wyk, N.; Watson, C.; Nagan, K.; MacCallum, M. Using self-determination theory to assess the attitudes of children and youth towards physical activity. Phys. Health Educ. J. 2013, 79, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N. The Body Appreciation Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2015, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R. Associations between body appreciation and disordered eating in a large sample of adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R.; Sirkaite, M. Associations between intuitive exercise, physical activity, exercise motivation, exercise habits and positive body image. Visuomenės Sveik. (Public Health) 2021, 4, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R.; Emeljanovas, A. Self-perception of physical activity and fitness is related to lower psychosomatic health symptoms in adolescents with unhealthy lifestyles. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 980–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, S.; Shephard, J. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can. J. Appl. Sport Sci. 1985, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaske, J.J.; Beaman, J.; Sponarski, C.C. Rethinking internal consistency in Cronbach’s Alpha. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Marques, M.M.; Silva, M.N.; Brunet, J.; Duda, J.L.; Haerens, L.; La Guardia, J.; Lindwall, M.; Lonsdale, C.; Markland, D.; et al. A classification of motivation and behavior change techniques used in self-determination theory-based interventions in health contexts. Motiv. Sci. 2020, 6, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, E.A.; Zurbriggen, E.L.; Monique, W.L. Becoming an object: A review of self-objectification in girls. Body Image 2020, 33, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Bennie, A.; Vasconcellos, D.; Cinelli, R.; Hilland, T.; Owen, K.B.; Lonsdale, C. Self-determination theory in physical education: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 99, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, E.; Zucchelli, F.; Costa, B.; Bhatia, R.; Halliwell, E.; Harcourt, D. A systematic review of interventions aiming to promote positive body image in children and adolescents. Body Image 2022, 42, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Oliva, D.; Sanchez-Miguel, P.A.; Leo, F.M.; Kinnafick, F.E.; García-Calvo, T.G. Physical education lessons and physical activity intentions within Spanish secondary schools: A self-determination perspective. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2014, 33, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.P.; Telford, R.M.; Telford, R.D.; Olive, L.S. Sport, physical activity and physical education experiences: Associations with functional body image in children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 45, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sun, S.; Zickgraf, H.F.; Lin, Z.; Fan, X. Meta-analysis of gender differences in body appreciation. Body Image 2020, 33, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Chiva-Bartoll, O.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Hortiguela-Alcala, D. Gender, physical self-perception and overall physical fitness in secondary school students: A multiple mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soos, I.; Dizmatsek, I.; Ling, J.; Ojelabi, A.; Simonek, J.; Boros-Balint, I.; Szabo, P.; Szabo, A.; Hamar, P. Perceived autonomy support and motivation in young people: A comparative investigation of physical education and leisure-time in four countries. Eur. J. Psychol. 2019, 15, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Measures | Range | Boys, n = 344 | Girls, n = 371 | Cohen‘ d | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leisure-time exercise (LTEQ) | 0–395 | 83.3 (54.7) | 58.4 (41.5) | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Physical activity habits | 1–7 | 4.3 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.2) | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Perceived teacher support of autonomy (LCQ) | 1–7 | 4.8 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.3) | - | 0.872 |

| Motivation for PE (PLOC-R) | −32.6–13.7 | −3.6 (9.5) | −6.6 (10.3) | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Perceived physical fitness | 1–5 | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.9) | 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Positive body image (BAS-2) | 1–5 | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.3 (1.0) | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| Study Measures | LTEQ | PAH | LCQ | PLOQ-R | PPF | BAS-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leisure-time exercise (LTEQ) | 1.00 | 0.32 ** | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.19 ** | 0.06 |

| Physical activity habits (PAH) | 0.25 ** | 1.00 | 0.20 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.18 ** |

| Perceived teacher support of autonomy (LCQ) | 0.003 | 0.20 ** | 1.00 | 0.47 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.21 ** |

| Motivation for PE (PLOC-R) | −0.03 | 0.17 ** | 0.33 ** | 1.00 | 0.25 ** | 0.32 ** |

| Perceived physical fitness (PPF) | 0.15 ** | 0.36 ** | −0.004 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 0.24 ** |

| Positive body image (BAS-2) | 0.13 * | 0.22 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.10 | 0.33 ** | 1.00 |

| Paths | β | 95% CI LB | 95% CI LB | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAS → MPE → PAH | 0.06 | −0.004 | 0.12 | 0.075 |

| TAS → MPE → PAH → PPF | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| TAS → MPE → PAH → PPF → BA | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.21 | <0.001 |

| MPE → PAH → PPF | 0.05 | −0.003 | 0.11 | 0.070 |

| MPE → PAH → PPF → BA | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.008 |

| PAH → PPF → BA | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jankauskiene, R.; Urmanavicius, D.; Baceviciene, M. Association between Motivation in Physical Education and Positive Body Image: Mediating and Moderating Effects of Physical Activity Habits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010464

Jankauskiene R, Urmanavicius D, Baceviciene M. Association between Motivation in Physical Education and Positive Body Image: Mediating and Moderating Effects of Physical Activity Habits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010464

Chicago/Turabian StyleJankauskiene, Rasa, Danielius Urmanavicius, and Migle Baceviciene. 2023. "Association between Motivation in Physical Education and Positive Body Image: Mediating and Moderating Effects of Physical Activity Habits" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010464

APA StyleJankauskiene, R., Urmanavicius, D., & Baceviciene, M. (2023). Association between Motivation in Physical Education and Positive Body Image: Mediating and Moderating Effects of Physical Activity Habits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010464