School Nurse Perspectives of Working with Children and Young People in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

4. Results

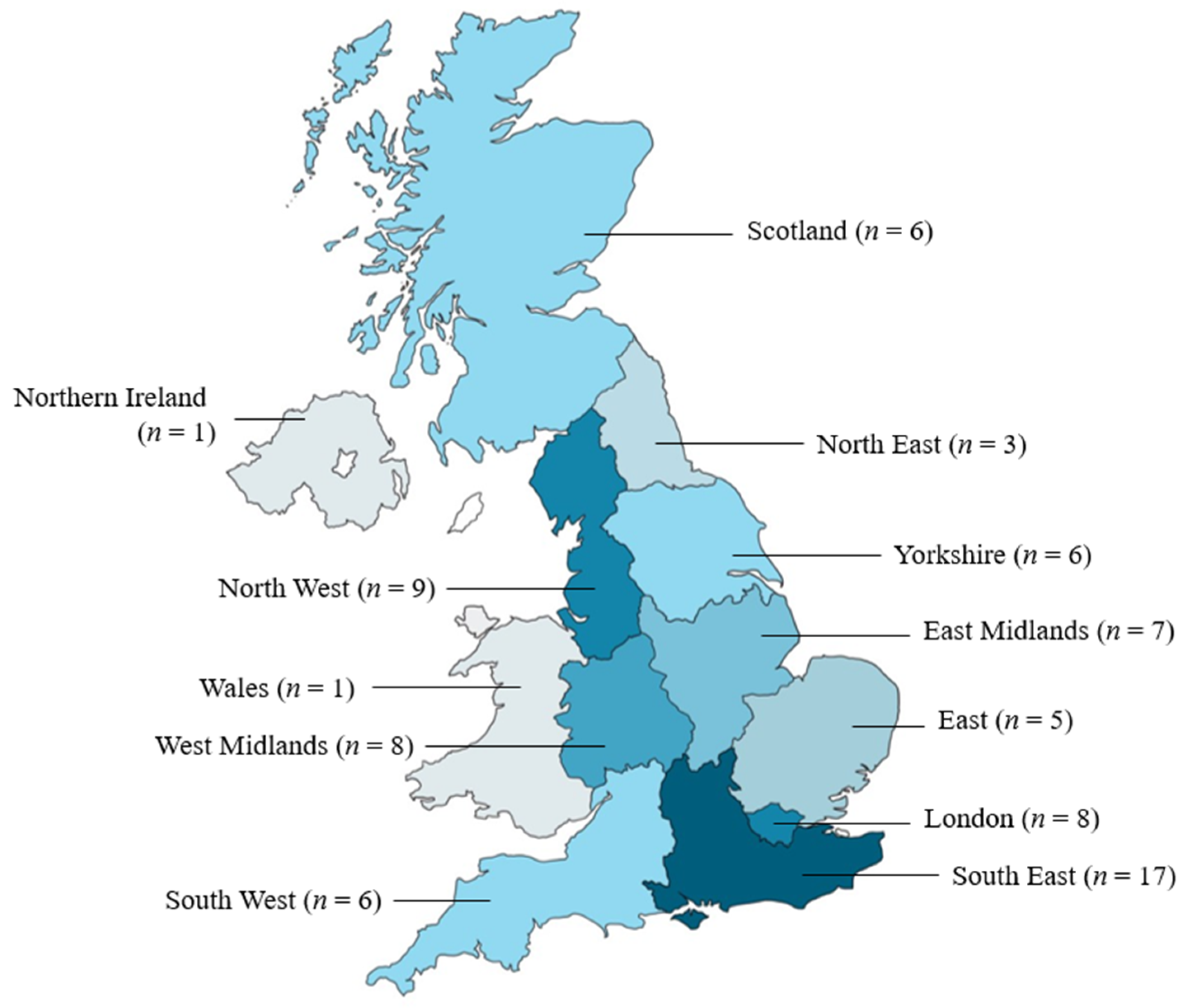

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Working during the Pandemic

4.1.2. Working with Vulnerable Children

4.2. Qualitative Findings

4.2.1. A Move from Preventive to Reactive School Nursing

4.2.2. Professional Challenges of Safeguarding in the Digital Context

4.2.3. The Changing Nature of Interprofessional Working

4.2.4. An Increasing Workload

4.2.5. Reduced Visibility and Representation of the Child

5. Discussion

- For professional organisations to continue to represent school nurses in relation to their changing work profile as a consequence of the pandemic. This will empower school nurses to negotiate the external expectations of their role;

- For governments and local authorities to recognise the value of the school nurse as a public health specialist by commissioning school health models that place experienced school nurses in leadership and coordination roles within school communities. These should be supported by a sufficient workforce to ensure effective preventive public health work;

- To recognise the strengths and limitations of virtual interprofessional meetings and utilise them accordingly (recognising that face-to-face meetings can be helpful for informal networking and discussion). This should be accompanied by clear directives on workload planning that recognise pre- and post-meeting work;

- To return to face-to-face contact with children and young people in health promotion, education and specialist work. This recognises the importance of building trust, ensuring confidentiality, and holistic assessment when working with children and young people;

- For local authorities to subscribe to a range of online/digital platforms that can form part of a toolkit for school nurses’ work with children and young people, employed according to assessed needs.

Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- School nurses are specialist public health nurses for children aged 5–19 (up to 24 years where indicated)

- Qualified school nurses have a post-registration Specialist Community and Public Health Nursing qualification

- School nurses work across education, health and with other partners to deliver the Healthy Child Programme (Public Health England, 2021)

- School nurses deliver health promotion programmes to improve health outcomes for children and young people (5–19 years)

- School nurses offer health education support for individual/groups of children and young people in specific health areas

- School nurses in state schools are commissioned by the local authority, or em-ployed directly in independent schools.

- Universal reach—supporting the development and healthy lifestyles for all chil-dren and young people

- Personalised/targeted response—supporting those who require additional support and need early help

- Specialist support—offered to children and young people with more complex or significant needs who may need help from multiple services working together.

References

- Royal College of Nursing. Improving Care in SEN Schools. The Royal College of Nursing. 2018. Available online: https://www.rcn.org.uk/magazines/Bulletin/2018/October/Improving-care-in-SEN-schools (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Royal College of Nursing. School Nursing. The Royal College of Nursing. 2022. Available online: https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/Children-and-young-people/School-nursing (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Public Health England. Health Visiting and School Nursing Service Delivery Model. GOV.UK. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/commissioning-of-public-health-services-for-children/health-visiting-and-school-nursing-service-delivery-model (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- School and Public Health Nurses Association. School Nursing: Creating a Healthy World in which Children Can Thrive. School and Public Health Nurses Association. 2021. Available online: https://saphna.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/SAPHNA-VISION-FOR-SCHOOL-NURSING.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Hoke, A.M.; Keller, C.M.; Calo, W.A.; Sekhar, D.L.; Lehman, E.B.; Kraschnewski, J.L. School Nurse Perspectives on COVID-19. J. Sch. Nurs. 2021, 37, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.L.; West, S.; Tang, A.C.; Cheng, H.Y.; Chong, C.Y.; Chien, W.T.; Chan, S.W. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of school nurses during COVID-19 pandemic as the frontline primary health care professionals. Nurs. Outlook 2021, 69, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsson, E.; Garmy, P.; Einberg, E.L. School Nurses’ Experience of Working in School Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Sweden. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Humphreys, K.L.; Myint, M.T.; Zeanah, C.H. Increased Risk for Family Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Katz, I.; Priolo-Filho, S.; Katz, C.; Andresen, S.; Bérubé, A.; Cohen, N.; Connell, C.M.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Fallon, B.; Fouche, A.; et al. One year into COVID-19: What have we learned about child maltreatment reports and child protective service responses? Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 130, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NSPCC. The Impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19): Statistics Briefing. NSPCC Learning. Available online: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/statistics-briefings/covid/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Isham, L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2047–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Green, P. Risks to children and young people during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020, 369, m1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, G.; Appleton, J.V.; Bekaert, S.; Harrold, T.; Taylor, J.; Sammut, D. School nursing: New ways of working with children and young people during the COVID-19 pandemic. A scoping review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A. A partnership with child and family. Sr. Nurse 1988, 8, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Firmin, C.E. Contextual Safeguarding: An Overview of the Operational, Strategic and Conceptual Framework. University of Bedfordshire. November 2017. Available online: https://uobrep.openrepository.com/handle/10547/624844 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Munro, E. Learning to Reduce Risk in Child Protection. Br. J. Soc. Work 2010, 40, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Appleton, J.V.; Coombes, L.; Harding, L. The Role of the School Nurse in Safeguarding Children And Young People: A Survey of Current Practice; Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Launder, M. RCN Calls for Boost in Number of School Nurses. Nursing in Practice. 2019. Available online: https://www.nursinginpractice.com/latest-news/rcn-calls-for-boost-in-number-of-school-nurses/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littler, N. A qualitative study exploring school nurses’ experiences of safeguarding adolescents. Br. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 14, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Qian, Y. COVID-19 and Adolescent Mental Health in the United Kingdom. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, U.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Vaillancourt, T.; Szatmari, P.; Georgiades, K.; Krygsman, A. The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of Canadian children and youth. Facets 2021, 6, 1628–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanou, E.; Belton, E.; Isolated and Struggling: Social Isolation and the Risk of Child Maltreatment, in Lockdown and Beyond. London: NSPCC. 2020. Available online: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/2020/social-isolation-risk-child-abuse-during-and-after-coronavirus-pandemic/ (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. Safeguarding Children. Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). 2022. Available online: https://www.scie.org.uk/children/safeguarding (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Cooper, A.L.; Brown, J.A.; Eccles, S.P.; Cooper, N.; Albrecht, M.A. Is nursing and midwifery clinical documentation a burden? An empirical study of perception versus reality. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1645–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawe, N.; Sealey, K. School nurses: Undervalued, underfunded and overstretched. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department for Education. Vulnerable Children and Young People Survey: Summary of Returns Waves 1 to 14 (December 2020). 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vulnerable-children-and-young-people-survey (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Department for Education. Vulnerable Children and Young People Survey: Summary of Returns Waves 1 to 26 (August 2021). 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vulnerable-children-and-young-people-survey (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Department for Education. Department for Education. Vulnerable Children and Young People Survey: Summary of Returns Waves 27 to 31 (January 2022). 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vulnerable-children-and-young-people-survey (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Wang, L.Y.; Vernon-Smiley, M.; Gapinski, M.A.; Desisto, M.; Maughan, E.; Sheetz, A. Cost-Benefit Study of School Nursing Services. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. Available online: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Sidpra, J.; Chhabda, S.; Gaier, C.; Alwis, A.; Kumar, N.; Mankad, K. Virtual multidisciplinary team meetings in the age of COVID-19: An effective and pragmatic alternative. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2020, 10, 1204–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrapese, B.; Gormley, J.M.; Deschene, K. Reimagining School Nursing: Lessons Learned from a Virtual School Nurse. NASN Sch. Nurse 2021, 36, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| What type of school(s) do you work with? (all that apply) | ||

| State | 70 | 88.6 |

| Independent | 14 | 17.7 |

| Special needs | 20 | 25.3 |

| Other | 3 | 3.8 |

| What age are the children you work with? (all that apply) | ||

| Primary school (ages 5–11) | 71 | 89.9 |

| Secondary school (ages 11–16) | 73 | 92.4 |

| Further education college | 26 | 32.9 |

| Which of the statements best describes the way you work with schools? (all that apply) | ||

| I am attached to one school | 7 | 8.9 |

| I am attached to one school and I am the main school nurse | 5 | 6.3 |

| I am attached to named schools | 7 | 8.9 |

| I am attached to named schools and I am the main school nurse | 29 | 36.7 |

| I am part of a school nursing team who share responsibility for schools in the area | 42 | 53.2 |

| What are your contracted hours as a school nurse? | ||

| Full time (all year) | 29 | 36.7 |

| Full time (term time only) | 7 | 8.9 |

| Part time (all year) | 20 | 25.3 |

| Part time (term time only) | 19 | 24.1 |

| Other | 4 | 5.1 |

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Were you redeployed? | ||

| Yes | 12 | 15.2 |

| No | 67 | 84.8 |

| Did your workload change during the COVID-19 pandemic? | ||

| No | 7 | 9.0 |

| Yes, it decreased | 13 | 16.7 |

| Yes, it increased | 58 | 74.4 |

| Did you experience a change in children’s, young people’s or families’ contact with the school nursing service during COVID-19? | ||

| No change in contact | 10 | 12.8 |

| Decreased contact | 47 | 60.3 |

| Increased contact | 21 | 26.9 |

| Increased | Same | Decreased | Never Used | Not Applicable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The modes of service delivery used by school nurses to communicate with children, young people and families | |||||

| Telephone consultations | 72 (91.1) | 5 (6.3) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 |

| Email * | 54 (69.2) | 17 (21.8) | 4 (5.1) | 3 (3.8) | 0 |

| Online/virtual consultations | 70 (88.6) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.3) | 0 |

| Online classroom session * | 28 (35.9) | 2 (2.6) | 10 (12.8) | 29 (36.7) | 9 (11.5) |

| Virtual nurses office ** | 27 (35.5) | 4 (5.1) | 3 (3.9) | 31 (40.8) | 11 (14.5) |

| Consultations outside, e.g., ‘Walk and Talk’ * | 29 (37.2) | 6 (7.7) | 4 (5.1) | 31 (39.7) | 8 (10.3) |

| Short health promotion videos | 43 (55.1) | 5 (6.4) | 1 (1.3) | 23 (29.5) | 6 (7.7) |

| Apps (such as ChatHealth) | 36 (45.6) | 14 (17.7) | 3 (3.8) | 20 (25.3) | 6 (7.6) |

| Other ^ | 8 (29.6) | 2 (7.4) | 0 | 0 | 17 (63.0) |

| The modes of communication used by school nurses to communicate with the multidisciplinary team | |||||

| Telephone consultations * | 63 (80.8) | 13 (16.7) | 2 (2.6) | 0 | 0 |

| 69 (87.3) | 9 (11.4) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0 | |

| Texting/WhatsApp *** | 39 (52.7) | 18 (24.3) | 1 (1.4) | 14 (18.9) | 2 (2.7) |

| Online/virtual meetings | 78 (98.7) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other ~ | 2 (11.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (88.2) |

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Did COVID-19 restrictions impact your ability to identify vulnerable children, young people and families? | ||

| Yes | 68 | 86.1 |

| No | 11 | 13.9 |

| Did COVID-19 restrictions impact your ability to provide support to vulnerable children, young people and families that were already known to you? | ||

| Yes | 63 | 79.7 |

| No | 16 | 20.3 |

| Overall, considering the impact of lockdown and the resulting changes in workload, what has been the impact of COVID-19 on school nursing partnership working? | ||

| It improved | 17 | 21.5 |

| It stayed the same | 9 | 11.4 |

| It was harder | 38 | 48.1 |

| It was variable | 15 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sammut, D.; Cook, G.; Taylor, J.; Harrold, T.; Appleton, J.; Bekaert, S. School Nurse Perspectives of Working with Children and Young People in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010481

Sammut D, Cook G, Taylor J, Harrold T, Appleton J, Bekaert S. School Nurse Perspectives of Working with Children and Young People in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010481

Chicago/Turabian StyleSammut, Dana, Georgia Cook, Julie Taylor, Tikki Harrold, Jane Appleton, and Sarah Bekaert. 2023. "School Nurse Perspectives of Working with Children and Young People in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010481

APA StyleSammut, D., Cook, G., Taylor, J., Harrold, T., Appleton, J., & Bekaert, S. (2023). School Nurse Perspectives of Working with Children and Young People in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010481