Partnering with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: An Evaluation Study Protocol to Strengthen a Comprehensive Multi-Scale Evaluation Framework for Participatory Systems Modelling through Indigenous Paradigms and Methodologies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

1.2. Participatory Systems Modelling (PSM) to Support the Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

1.3. Maximizing Opportunities in PSM—Culturally Appropriate and Empowering Evaluation Approaches by Partnering with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities

1.4. Aims and Objectives

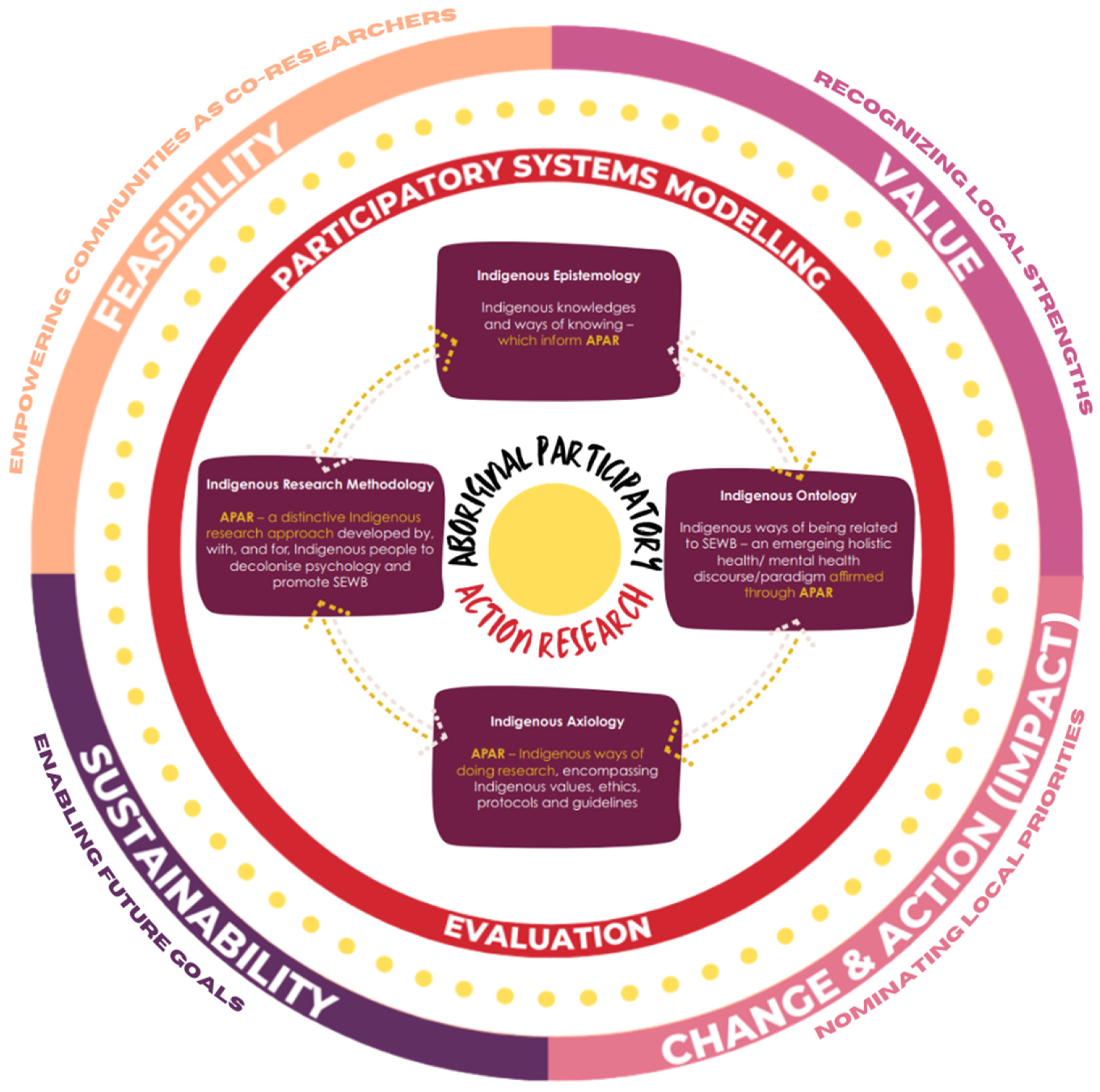

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Community Inclusion & Recruitment Procedure

2.3. Ownership and Control over Indigenous Data (Data Sovereignty)

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Data Analysis Plan

2.6. Data Security and Protection

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACCHS | Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services |

| APAR | Aboriginal Participatory Action Research |

| PAR | Participatory Action Research |

| PSM | Participatory Systems Modelling |

| Program | Right care, first time, where you live research Program |

References

- Green, N. Under The Milky Way. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice; Dudgeon, P.B.A., Darlaston-Jones, D., Walker, R., Eds.; Commonwealth of Australia: Barton, ACT, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Calma, T.; Dudgeon, P.; Bray, A. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing and Mental Health. Aust. Psychol. 2017, 52, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adolescent and Youth Health and Wellbeing 2018: In Brief. 2018. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/e9434481-c52b-4a79-9cb5-94f72f04d23e/aihw-ihw-198.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Transforming Indigenous Mental Health and Well Being. Social & Emotional Wellbeing Gathering: 30–31 March 2021. 2021. Available online: https://timhwb.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/SEWB-Gathering-Report-2021.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Sherwood, J. Colonisation—It’s bad for your health: The context of Aboriginal health. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 46, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooda, M.; Dudgeon, P. The Elders’ Report into Preventing Indigenous Self-Harm and Youth Suicide; People Culture Environment: Barton, ACT, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McGorry, P.D.; Goldstone, S.D.; Parker, A.; Rickwood, D.; Hickie, I. Cultures for mental health care of young people: An Australian blueprint for reform. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnell, D.; Kidger, J.; Elvidge, H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. BMJ 2018, 361, k2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nearchou, F.; Flinn, C.; Niland, R.; Subramaniam, S.S.; Hennessy, E. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, F.; Ali, S.; Benmarhnia, T.; Pearl, M.; Massazza, A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Scott, J.G. Climate Change and Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konish, L. 80% of Economists See ‘Stagflation’ as a Long-Term Risk. What It Is and How to Prepare for It. CNBC. 2022. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/06/21/what-stagflation-is-and-how-to-prepare-for-it.html (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, E.; Heritage, B.; Shepherd, C.; Marriott, R. Measuring Social and Emotional Wellbeing in Aboriginal Youth Using Strong Souls: A Rasch Measurement Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.; Stuart, J.; Leske, S.; Ward, R.; Tanton, R. Suicide rates for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: The influence of community level cultural connectedness. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 214, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silburn, S.; Robinson, G.; Leckning, B.; Henry, D.; Cox, A.; Kickett, D. Preventing Suicide Among Aboriginal Australians. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Dudgeon, P.H.M., Walker, R., Eds.; Commonwealth Government of Australia: Barton, ACT, Australia, 2014; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Indigenous Income and Finance AIHW. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-income-and-finance (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- United Nations Association of Australia. Australia’s First Nations Incarceration Epidemic: Origins of Overrepresentation and a Path Forward. Available online: https://www.unaa.org.au/2021/03/18/australias-first-nations-incarceration-epidemic-origins-of-overrepresentation-and-a-path-forward/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Mission Australia. Youth Survey Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/publications/youth-survey/2087-mission-australia-youth-survey-report-2021/file (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Dudgeon, P.; Bray, A.; D’Costa, B.; Walker, R. Decolonising Psychology: Validating Social and Emotional Wellbeing. Aust. Psychol. 2017, 52, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.; Bolt, R.; Botfield, J.R.; Martin, K.; Doyle, M.; Murphy, D.; Graham, S.; Newman, C.E.; Bell, S.; Treloar, C.; et al. Beyond deficit: ‘Strengths-based approaches’ in Indigenous health research. Sociol. Health Illn. 2021, 43, 1405–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davy, C.; Harfield, S.; McArthur, A.; Munn, Z.; Brown, A. Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: A framework synthesis. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nolan-Isles, D.; Macniven, R.; Hunter, K.; Gwynn, J.; Lincoln, M.; Moir, R.; Dimitropoulos, Y.; Taylor, D.; Agius, T.; Finlayson, H.; et al. Enablers and Barriers to Accessing Healthcare Services for Aboriginal People in New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reifels, L.; Nicholas, A.; Fletcher, J.; Bassilios, B.; King, K.; Ewen, S.; Pirkis, J. Enhanced primary mental healthcare for Indigenous Australians: Service implementation strategies and perspectives of providers. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2018, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.J.C.; Rosenberg, S.; Smith, B.; Occhipinti, J.; Mendoza, J.; Freebairn, L.; Skinner, A.; Hickie, I.B. Missing in action: The right to the highest attainable standard of mental health care. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Luke, J.N.; Ferdinand, A.S.; Paradies, Y.; Chamravi, D.; Kelaher, M. Walking the talk: Evaluating the alignment between Australian governments’ stated principles for working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health contexts and health evaluation practice. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, S.J.; Rogers, J.E. International Human Rights and Indigenous Peoples; Aspen Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Indigenous Australians Agency. 3.14 Access to Services Compared with Need. Available online: https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/3-14-access-services-compared-with-need/data#DataVisualisation (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 6.6 Indigenous Australians’ Access to Health Services. 2016. Australia’s Health 2016. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/01d88043-31ba-424a-a682-98673783072e/ah16-6-6-indigenous-australians-access-health-services.pdf.aspx (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Beks, H.; Amos, T.; Bell, J.; Ryan, J.; Hayward, J.; Brown, A.; Mckenzie, C.; Allen, B.; Ewing, G.; Hudson, K.; et al. Participatory research with a rural Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation: Lessons learned using the CONSIDER statement. Rural Remote Health 2022, 22, 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Brown, A.; Dudgeon, P.; McPhee, R.; Coffin, J.; Pearson, G.; Lin, A.; Newnham, E.; Baguley, K.K.; Webb, M.; et al. Our journey, our story: A study protocol for the evaluation of a co-design framework to improve services for Aboriginal youth mental health and well-being. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepworth, J.; Askew, D.; Foley, W.; Duthie, D.; Shuter, P.; Combo, M.; Clements, L.A. How an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care service improved access to mental health care. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Walker, C.; Loring, B.; Paine, S.-J.; Reid, P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti, J.; Skinner, A.; Doraiswamy, P.M.; Fox, C.; Herrman, H.; Saxena, S.; London, E.; Song, Y.J.C.; Hickie, I.B. Mental health: Build predictive models to steer policy. Nature 2021, 597, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haswell, M.R.; Kavanagh, D.; Tsey, K.; Reilly, L.; Cadet-James, Y.; Laliberte, A.; Wilson, A.; Doran, C. Psychometric Validation of the Growth and Empowerment Measure (GEM) Applied with Indigenous Australians. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, D.A.; Stamatakis, K.A. Systems science methods in public health: Dynamics, networks, and agents. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2012, 33, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Freebairn, L.; Song, Y.J.C.; Occhipinti, J.; Huntley, S.; Dudgeon, P.; Robotham, J.; Lee, G.Y.; Hockey, S.; Gallop, G.; Hickie, I.B. Applying systems approaches to stakeholder and community engagement and knowledge mobilisation in youth mental health system modelling. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of Sydney. Right Care, First Time, Where You Live. Available online: https://www.sydney.edu.au/brain-mind/our-research/youth-mental-health-and-technology/right-care-first-time-where-you-live-program.html (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Gee, G.; Dudgeon, P.; Schultz, C.; Hart, A.; Kelly, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Dudgeon, P.H.M., Walker, R., Eds.; Commonwealth Government of Australia: Barton, ACT, Australia, 2014; pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Occhipinti, J.; Skinner, A.; Carter, S.; Heath, J.; Lawson, K.; McGill, K.; McClure, R.; Hickie, I.B. Federal and state cooperation necessary but not sufficient for effective regional mental health systems: Insights from systems modelling and simulation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freebairn, L.; Occhipinti, J.; Song, Y.J.C.; Skinner, A.; Lawson, K.; Lee, G.Y.; Hockey, S.J.; Huntley, S.; Hickie, I.B. Participatory Methods for Systems Modeling of Youth Mental Health: Implementation Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e32988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.Y.; Hickie, I.B.; Occhipinti, J.; Song, Y.J.C.; Camacho, S.; Skinner, A.; Lawson, K.; Hockey, S.J.; Hilber, A.M.; Freebairn, L. Participatory Systems Modelling for Youth Mental Health: An Evaluation Study Applying a Comprehensive Multi-Scale Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y.; Hickie, I.B.; Occhipinti, J.; Song, Y.J.C.; Skinner, A.; Camacho, S.; Lawson, K.; Hilber, A.M.; Freebairn, L. Presenting a comprehensive multi-scale evaluation framework for participatory modelling programs: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.D.; Occhipinti, J.; Freebairn, L.; Skinner, A.; Song, Y.J.C.; Lee, G.Y.; Huntley, S.; Hickie, I.B. A Dynamic Approach to Economic Priority Setting to Invest in Youth Mental Health and Guide Local Implementation: Economic Protocol for Eight System Dynamics Policy Models. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, D. The Quiet Movement to Make Government Fail Less Often. The New York Times. 2014. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/15/upshot/the-quiet-movement-to-make-government-fail-less-often.html (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Bainbridge, R.; Tsey, K.; McCalman, J.; Kinchin, I.; Saunders, V.; Lui, F.W.; Cadet-James, Y.; Miller, A.; Lawson, K. No one’s discussing the elephant in the room: Contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian health research. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission. Indigenous Evaluation Strategy: Productivity Commission Background Paper. 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/indigenous-evaluation/strategy/indigenous-evaluation-background.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Productivity Commission. Indigenous Evaluation Strategy 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/indigenous-evaluation/strategy/indigenous-evaluation-strategy.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Leeson, S.; Smith, C.; Rynne, J. Yarning and appreciative inquiry: The use of culturally appropriate and respectful research methods when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Australian prisons. Methodol. Innov. 2016, 9, 2059799116630660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelaher, M.; Luke, J.; Ferdinand, A.; Chamravi, D.; Ewen, S.; Paradies, Y. An Evaluation Framework to Improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health; Lowitja Institute: Collingwood, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sherriff, S.L.; Miller, H.; Tong, A.; Williamson, A.; Muthayya, S.; Redman, S.; Bailey, S.; Eades, S.; Haynes, A. Building trust and sharing power for co-creation in Aboriginal health research: A stakeholder interview study. Evid. Policy 2019, 15, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission. Romlie Mokak: Commissioner. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/about/people-structure/commissioners/romlie-mokak (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Productivity Commission. A Guide to Evaluation under the Indigenous Evaluation Strategy 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/indigenous-evaluation/strategy/indigenous-evaluation-guide.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Jordan, R.; Gray, S.; Zellner, M.; Glynn, P.D.; Voinov, A.; Hedelin, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Leong, K.; Olabisi, L.S.; Hubacek, K.; et al. Twelve Questions for the Participatory Modeling Community. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, B.; Gray, S.; Woehlke, S.; BenDor, T.; Singer, A.; Jordan, R.; Zellner, M.; Giabbanelli, P.; Glynn, P.; Jenni, K.; et al. What’s left before participatory modeling can fully support real-world environmental planning processes: A case study review. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 143, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, P.B.A.; Darlaston-Jones, D.; Walker, R. Aboriginal Participatory Action Research: An Indigenous Research Methodology Strengthening Decolonisation and Social and Emotional Wellbeing. 2020. Available online: https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Document/Lowitja-Publishing/LI_Discussion_Paper_P-Dudgeon_FINAL3.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Fogarty, W.; Lovell, M.; Langenberg, J.; Heron, M.J. Deficit Discourse and Strengths-Based Approaches: Changing the Narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health And Wellbeing; Lowitja Institute: Collingwood, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.; Hole, R.; Berg, L.D.; Hutchinson, P.; Sookraj, D. Common Insights, Differing Methodologies:Toward a Fusion of Indigenous Methodologies, Participatory Action Research, and White Studies in an Urban Aboriginal Research Agenda. Qual. Inq. 2009, 15, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council. AH&MRC Ethical Guidelines: Key Principles V2.0. 2020. Available online: https://www.ahmrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/V2.0-Key-principles-Updated.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Huria, T.; Palmer, S.C.; Pitama, S.; Beckert, L.; Lacey, C.; Ewen, S.; Smith, L.T. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: The CONSIDER statement. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fitzpatrick, E.F.M.; Martiniuk, A.L.C.; D’Antoine, H.; Oscar, J.; Carter, M. Elliott, E.J. Seeking consent for research with indigenous communities: A systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 2016, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. In Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda; Kukutai, T.; Taylor, J. (Eds.) Australian National University Press: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barlo, S.; Boyd, W.E.; Pelizzon, A.; Wilson, S. Yarning as protected space: Principles and protocols. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2020, 16, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M. Indigenous Statistics: A Quantitative Research Methodology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, A.-L.; McLellan, S.; Willis, E.; Curnow, V.; Harvey, C.; Brown, J.; Hegney, D. Yarning as an Interview Method for Non-Indigenous Clinicians and Health Researchers. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Alexi, J.; Badcock, D.; Darlaston-Jones, D.; Derry, K.; Dudgeon, P.; Gray, P.; Hirvonen, T.; Kashyap, S.; Norris, K.; et al. Evidence-Based Practice and Practice-Based Evidence in Psychology. 2022. Available online: https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/8b55fa8d-53df-4fae-bade-44d8c8e2fdb4/aps-position-statement-evidence-based-practice-and-practice-based-evidence-in-psychology.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Lee, G.Y.; Hickie, I.; Occhipinti, J.; Song, Y.J.C.; Huntley, S.; Skinner, A.; Lawson, K.; Hockey, S.J.; Freebarin, L. Prototyping, developing, and iterating a gamified survey to evaluate participatory systems modelling for youth mental health: Quality assurance pilot. In Proceedings of the 24th International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 5–10 December 2021; Available online: https://116.90.59.164/modsim2021/papers/H2/lee.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Yunkaporta, T.M.D. Thought Ritual: An Indigenous Data Analysis Method. In Proceedings of the AIATSIS National Indigenous Research Conference 2019, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 1–3 July 2019; Available online: https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/research_pub/thought_ritual_-_an_indigenous_data_analysis_method_for_research.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. A Guide to Applying the AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research. 2020. Available online: https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-02/aiatsis-guide-code-ethics-jan22.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds First Nations Cohort Research Team. “All About Us”: Indigenous Data Analysis Workshop—Capacity Building in the Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds First Nations Cohort. CJC Open 2019, 1, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of Sydney. Research Data Management Policy 2014. 2021. Available online: https://www.sydney.edu.au/policies/showdoc.aspx?recnum=PDOC2013/337&RendNum=0 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- The University of Sydney. Research Data Management Procedures 2015. 2020. Available online: https://www.sydney.edu.au/policies/showdoc.aspx?recnum=PDOC2014/366&RendNum=0 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Australian Government. National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–2023. 2017. Available online: https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/mhsewb-framework_0.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Productivity Commission. Mental Health Productivity Commission Inquiry Report 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report/mental-health-volume1.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Australian Government. Closing the Gap. Available online: https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/ (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Australian Government: National Mental Health Commission. Commitment to National Mental Health Reform Takes a Key Step. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/News-and-media/media-releases/2022/March/Commitment-to-national-mental-health-reform-takes (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Krusz, E.; Davey, T.; Wigginton, B.; Hall, N. What Contributions, if Any, Can Non-Indigenous Researchers Offer Toward Decolonizing Health Research? Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, G.Y.; Robotham, J.; Song, Y.J.C.; Occhipinti, J.-A.; Troy, J.; Hirvonen, T.; Feirer, D.; Iannelli, O.; Loblay, V.; Freebairn, L.; et al. Partnering with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: An Evaluation Study Protocol to Strengthen a Comprehensive Multi-Scale Evaluation Framework for Participatory Systems Modelling through Indigenous Paradigms and Methodologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010053

Lee GY, Robotham J, Song YJC, Occhipinti J-A, Troy J, Hirvonen T, Feirer D, Iannelli O, Loblay V, Freebairn L, et al. Partnering with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: An Evaluation Study Protocol to Strengthen a Comprehensive Multi-Scale Evaluation Framework for Participatory Systems Modelling through Indigenous Paradigms and Methodologies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Grace Yeeun, Julie Robotham, Yun Ju C. Song, Jo-An Occhipinti, Jakelin Troy, Tanja Hirvonen, Dakota Feirer, Olivia Iannelli, Victoria Loblay, Louise Freebairn, and et al. 2023. "Partnering with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: An Evaluation Study Protocol to Strengthen a Comprehensive Multi-Scale Evaluation Framework for Participatory Systems Modelling through Indigenous Paradigms and Methodologies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010053