Unequal Access and Use of Health Care Services among Settled Immigrants, Recent Immigrants, and Locals: A Comparative Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey in Chile

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Sociodemographic variables: Sex (male/female) and age as categorical variables (0–18, 19–30, 31–65, 66 or more).

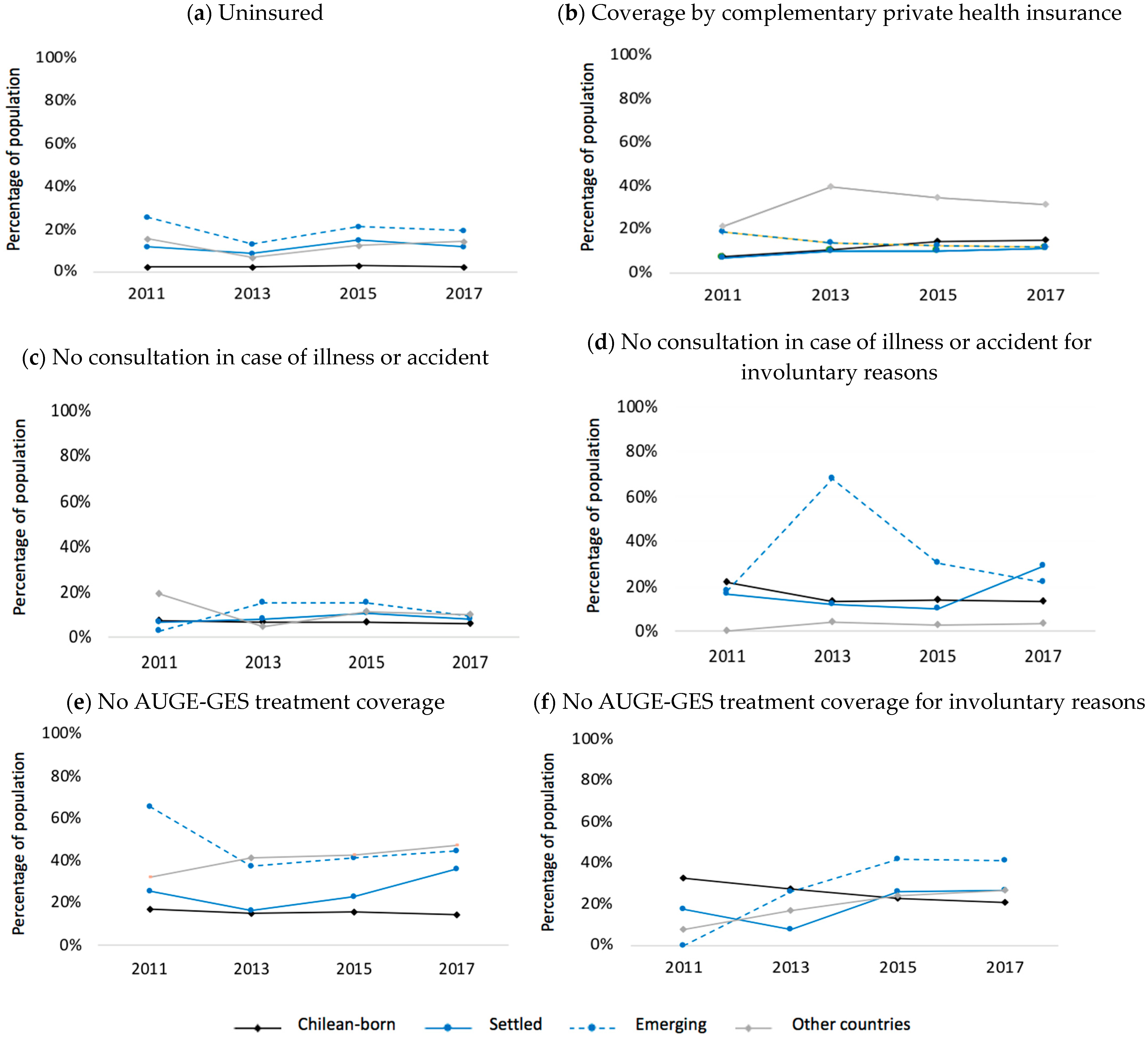

- Health care insurance: the public system called FONASA (nationally categorized according to beneficiaries’ income and financial contribution as A–B, C–D, do not know), the private system called ISAPRE, None, and others.

- Coverage by complementary private health insurance: whether complementary Health Insurance covers any family member in case of illness or accident (yes/no).

- Expressed demand for health care services: (i) Consultation or medical attention derived from some illness or accident during the three months before the survey (yes/no); (ii) treatment coverage for diseases included in the Explicit Health Guarantees plan (AUGE-GES) by its corresponding system (yes/no).

- Unexpressed demand for health care services for voluntary or involuntary reasons: Reasons for not consulting or not having universal health coverage to selected 84 health conditions included in the AUGE-GES Chilean Law (which ensure equal access to diagnosis and treatment regardless of health insurance status). Reasons were categorized into the following voluntary reasons: preference for another physician, alternative medicine or pharmacy attention, decided not to wait for attention, lack of time, preferred self-administered usual medications, did not consider it necessary, had a better plan. Meanwhile, involuntary reasons included difficulty arriving at the place of care, lack of healthcare coverage for their specific needs or those related to a particular age group, not obtaining an appointment, lack of knowledge, lack of time or financial sources, medical recommendation, another reason.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Explanation of the Results

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

4.4. Implications in Public Health, Health Services, and Suggestions for Future Research

- Monitor the effective implementation of Supreme Decree no. 67 (Decreto Supremo no. 67) in public healthcare centers.

- Train healthcare workers and administrative staff on migrants’ right to access healthcare and on cross-cultural skills.

- Provide clear, culturally and linguistically adequate information on the right to health of international migrants regardless of migratory status to migrant communities and how to navigate the healthcare system.

- Design, pilot, and implement specific programs at the local level to address the challenges faced by recently arrived emerging migrants from an intersectoral perspective.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orcutt, M.; Spiegel, P.; Kumar, B.; Abubakar, I.; Clark, J.; Horton, R.; Migration, L. Lancet Migration: Global collaboration to advance migration health. Lancet 2020, 395, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Orgnization. Migration and Health: Key Issues. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/migration-and-health/migration-and-health-in-the-european-region/migration-and-health-key-issu (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Castelli, F. Drivers of migration: Why do people move? J. Travel Med. 2018, 25, tay040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, U. Globalization, migration, and ethnicity. Public Health 2019, 172, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerrutti, M.; Parrado, E. Intraregional migration in South America: Trends and a research agenda. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Estimación de Personas Extranjeras Residentes Habituales en Chile al 31 de Diciembre de 2020. Available online: https://www.extranjeria.gob.cl/media/2021/08/Estimaci%C3%B3n-poblaci%C3%B3n-extranjera-en-Chile-2020-regiones-y-comunas-metodolog%C3%ADa.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Características de la Inmigración Internacional en Chile, Censo 2017; INE: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- UNHCR. Update North of Chile, March 2022. 2022. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/chile/update-north-chile-march-2022 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia. Inmigrantes Síntesis de Resultados. Available online: http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/storage/docs/casen/2017/Resultados_Inmigrantes_casen_2017.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Cabieses, B. Encuesta Sobre COVID-19 a Poblaciones Migrantes Internacionales en Chile: Informe de Resultados Completo; Instituto de Ciencias e Innovación en Medicina (ICIM): Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pedemonte, N.R.; Undurraga, J.T.V. Migración en Chile: Evidencia y mitos de una Nueva Realidad; LOM Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bastías, G. Reforma al Sistema Privado de Salud: Comentarios al Proyecto de Ley Que Modifica el Sistema Privado de Salud ya las Indicaciones Presentadas en Julio de 2019 (Boletín 8105-11); Centro de Políticas Públicas Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cid, C.; Torche, A.; Herrera, C.; Bastías, G.; Barrios, X. Bases para una reforma necesaria al seguro social de salud chileno. In Centro de Políticas Públicas. Propuestas Para Chile. Santiago: Universidad Católica de Chile; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2013; pp. 183–219. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Orgnization. Resolution WHA61. 17. Health of migrants. In Sixty-first World Health Assembly; Agenda item 11.9; World Health Orgnization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Documento de Orientación Sobre Migración y Salud; Regional Office for the Americas of the World Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Estrategia Nacional de Salud Para el Cumplimiento de los Objetivos Sanitarios de la Década 2011–2020; Subsecretaría de Salud Pública/División de Planificación Sanitaria/Ministerio de Salud de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2011.

- Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Política De Salud De Migrantes Internacionales en Chile. 2017. Available online: http://redsalud.ssmso.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Politica-de-Salud-de-Migrantes-310-1750.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Wiff, J.I.; Benítez, A.F.; González, M.P.; Padilla, C.; Chepo, M.; Flores, R.L. The National Health Policy for International Migrants in Chile, 2014–2017. In Governing Migration for Development from the Global Souths; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, Belgium, 2022; pp. 338–364. [Google Scholar]

- Markkula, N.; Cabieses, B.; Lehti, V.; Uphoff, E.; Astorga, S.; Stutzin, F. Use of health services among international migrant children—A systematic review. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.Q.; Hwang, S.H. Explaining Immigrant Health Service Utilization: A Theoretical Framework. SAGE Open 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabieses, B.; Bird, P. Glossary of access to health care and related concepts for low-and middle-income countries (LMICs): A critical review of international literature. Int. J. Health Serv. 2014, 44, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliford, M.; Figueroa-Munoz, J.; Morgan, M.; Hughes, D.; Gibson, B.; Beech, R.; Hudson, M. What does’ access to health care’mean? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabieses, B.; Oyarte, M. Health access to immigrants: Identifying gaps for social protection in health. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Rada, I.; Oyarte, M.; Cabieses, B. A comparative analysis of health status of international migrants and local population in Chile: A population-based, cross-sectional analysis from a social determinants of health perspective. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astorga-Pinto, S.M.; Cabieses, B.; Calderon, A.C.; McIntyre, A.M. Percepciones sobre acceso y uso de servicios de salud mental por parte de inmigrantes en Chile, desde la perspectiva de trabajadores, autoridades e inmigrantes. Rev. Del Instig. Salud Pública Chile 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blukacz, A.; Cabieses, B.; Markkula, N. Inequities in mental health and mental healthcare between international immigrants and locals in Chile: A narrative review. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, A.; Toffoletto, C.; Labra, P.; Hidalgo, G.; Pérez, S. Barreras en acceso a control preventivo en padres migrantes de infantes en Santiago, Chile, 2018. Rev. Salud Pública 2022, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obach, A.; Hasen, F.; Cabieses, B.; D’Angelo, C.; Santander, S. Conocimiento, acceso y uso del sistema de salud en adolescentes migrantes en Chile: Resultados de un estudio exploratorio. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernales, M.; Cabieses, B.; McIntyre, A.M.; Chepo, M. Challenges in primary health care for international migrants: The case of Chile. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.L.; Pino, B.D.A.; García, A.F.B.; Acevedo, V.A.B.; Silva, D.R.C.; Ojeda, I.A.M. Acceso y conocimiento de inmigrantes haitianos sobre la Atención Primaria de Salud chilena. Benessere Rev. Enfermería 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Cabieses, B.; Obach, A.; Gálvez, P.; Correa, M.E. Maternidad y Salud Mental de Mujeres Haitianas Migrantes en Santiago de Chile: Un Estudio Cualitativo. Castalia-Revista De Psicología De La Academia 2022, 38, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabieses, B.; Blukacz, A. Reforzar el acceso a la salud en el contexto de Covid-19 en migrantes recién llegados a Chile. Rev. Chil. Salud Pública 2020, 24, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIM. Informe Migratorio Sudamericano Nº3: Tendencias migratorias en América del Sur; Oficina Regional de la OIM: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Arellano, J.-L.; Carranza-Rodriguez, C. Estrategias de cribado en población inmigrante recién llegada a España. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2016, 34, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, A.A.; Basten, A.; Frattini, C. Migration: A social determinant of the health of migrants. Eurohealth 2009, 16, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.A.; Blake, C.; Dhavan, P. Social determinants and risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in South Asian migrant populations in Europe. Asia Eur. J. 2011, 8, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, E.A. Progreso, retos y la equidad en Plan AUGE (Acceso Universal con Garantías Explícitas en Salud (2005–2020). Estudios 2022, 44, 88–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, O. AUGE y caída de una política pública en salud en Chile. Cuad. Médico Soc. 2015, 55, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chepo, M.; Cabieses, B. Gaps in access to health among internationals migrants and Chileans under 18 years: CASEN analysis 2015–2017. Medwave 2019, 19 (Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar]

- Vega, C.V.Z.; Campos, M.C.G. Discriminación y exclusión hacia migrantes en el sistema de salud chileno. Una revisión sistematizada. Salud Soc. 2019, 10, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, T. The Effect of Health Change on Long-Term Settlement Intentions of International Immigrants in New Destination Countries: Evidence from Yiwu City in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabieses, B.; Pickett, K.E.; Tunstall, H. Comparing sociodemographic factors associated with disability between immigrants and the Chilean-born: Are there different stories to tell? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 4403–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabieses, B.; Tunstall, H.; Pickett, K. Testing the Latino paradox in Latin America: A population-based study of Intra-Regional Immigrants in Chile. Rev. Med. Chile 2013, 141, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agar Corbinos, L.; Delgado, I.; Oyarte, M.; Cabieses, B. Salud Y Migración: Análisis Descriptivo Comparativo De Los Egresos Hospitalarios De La Población Extranjera Y Chilena (Health and Migration: A Comparative Descriptive Analysis of Hospital Discharges in the Foreign and Chilean Populations). Oasis 2017, 25, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Betancour, M.C.; Pérez-González, C. Caracterización de las consultas de la población migrante adulta en un servicio de urgencia público del área norte de Santiago de Chile durante 201. Rev. Salud Pública 2020, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Denier, N.; Wang, J.S.-H.; Kaushal, N. Unhealthy assimilation or persistent health advantage? A longitudinal analysis of immigrant health in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 195, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raposo, V.L.; Violante, T. Access to Health Care by Migrants with Precarious Status During a Health Crisis: Some Insights from Portugal. Hum. Rights Rev. 2021, 22, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierola, M.; Rodríguez, M. Migrantes en América Latina: Disparidades en el estado de salud y en el acceso a la atención médica. Doc. Para Discusión BID 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Campo, V.A.; Valenzuela-Suazo, S.V. Migrantes y sus condiciones de trabajo y salud: Revisión integrativa desde la mirada de enfermería. Esc. Anna Nery 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, W.; Miranda, J.J.; Mendoza, W.; Miranda, J.J. La inmigración venezolana en el Perú: Desafíos y oportunidades desde la perspectiva de la salud. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2019, 36, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanes-García, Y.E.; Ghys, T. Barriers to access healthcare for Middle American Migrants during transit in Mexico. Rev. Política Glob. Y Ciudad. 2021, 7, 182–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bojorquez-Chapela, I.; Flórez-García, V.; Calderón-Villarreal, A.; Fernández-Niño, J.A. Health policies for international migrants: A comparison between Mexico and Colombia. Health Policy OPEN 2020, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouratt, C.E.; Voorend, K. Esquivando al Estado. Prácticas privadas en el uso de los servicios de salud entre inmigrantes nicaragüenses en Costa Rica. Anu. Estud. Centroam. 2019, 45, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, S.C. Mujeres que migran: Atención en salud sexual y reproductiva a migrantes afrocaribeñas en Uruguay. Encuentros Latinoam. 2018, 2, 49–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bojorquez, I.; Cabieses, B.; Arósquipa, C.; Arroyo, J.; Novella, A.C.; Knipper, M.; Orcutt, M.; Sedas, A.C.; Rojas, K. Migration and health in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Lancet 2021, 397, 1243–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.D. Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2019, 49, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent, C.; Larchanché, S. Transnational migration and global health: The production and management of risk, illness, and access to care. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2011, 40, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antognini, A.F.; Trebilcock, M.P. Pandemia, inequidad y protección social neoliberal: Chile, un caso paradigmático. Braz. J. Lat. Am. Stud. 2021, 20, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Laborde, C.; Aguilera-Sanhueza, X.; Hirmas-Adauy, M.; Matute, I.; Delgado-Becerra, I.; Ferrari, M.N.-D.; Olea-Normandin, A.; González-Wiedmaier, C. Health insurance scheme performance and effects on health and health inequalities in Chile. MEDICC Rev. 2017, 19, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crispi, F.; Cherla, A.; Vivaldi, E.A.; Mossialos, E. Rebuilding the broken health contract in Chile. Lancet 2020, 395, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, F.; Nazzal, C.; Cerecera, F.; Ojeda, J.I. Reducing health inequalities: Comparison of survival after acute myocardial infarction according to health provider in Chile. Int. J. Health Serv. 2019, 49, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Rojas, G.; Fritsch, R.; Frank, R.; Lewis, G. Inequities in mental health care after health care system reform in Chile. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, L.; Asencio, F.; Gandini, V.; Freitez, A.; Serrano, D.; Salazar, G.; Franco, A.; Zapata, G.; Cuervo, S.; Herrera, G.; et al. Crisis y Migración de Población Venezolana. Entre la Desprotección y la Seguridad Jurídica en Latinoamérica; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberona Concha, N.P.; Piñones Rivera, C.D.; Dilla Alfonso, H. De la migración forzada al tráfico de migrantes: La migración clandestina en tránsito de Cuba hacia Chile. Migr. Int. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, V.; Umpierrez de Reguero, S. Inclusive language for exclusive policies: Restrictive migration governance in Chile, 2018. Lat. Am. Policy 2020, 11, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefoni, C.; Brito, S. Migraciones y Migrantes en los Medios de Prensa en Chile: La Delicada Relación Entre las Políticas de Control y los Procesos de Racialización. Revista de Historia Social Y De Las Mentalidades 2019, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abal, Y.S.; Melella, C.E.; Matossian, B. Sobre otredades y derechos: Narrativas mediáticas y normativas sobre el acceso de la población migrante a la salud pública. Astrolabio 2020, 169–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, N. Pathogenic Policy: Immigrant Policing, Fear, and Parallel Medical Systems in the US South. Med. Anthropol. 2017, 36, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philbin, M.M.; Flake, M.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Hirsch, J.S. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 199, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.J.; Lopez, W.D.; Mesa, H.; Rion, R.; Rabinowitz, E.; Bryce, R.; Doshi, M. A qualitative study on the impact of the 2016 US election on the health of immigrant families in Southeast Michigan. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Callaghan, T.; Washburn, D.J.; Nimmons, K.; Duchicela, D.; Gurram, A.; Burdine, J. Immigrant health access in Texas: Policy, rhetoric, and fear in the Trump era. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larenas-Rosa, D.; Cabieses, B. Acceso a salud de la población migrante internacional en situación irregular: La respuesta del sector salud en Chile. Cuad. Méd. Soc. 2018, 58, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Sex | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–18 | 19–30 | 31–65 | 66 o more | Men | Women | ||

| Chilean-born | 2011 | 28.3% (27.8–28.9%) n = 4,702,212 | 20.0% (19.5–20.5%) n = 3,308,622 | 41.4% (41.0–41.9%) n = 6,864,780 | 10.3% (9.8–10.7%) n = 1,701,925 | 47.6% (47.2–48.0%) n = 7,895,139 | 52.4% (52.0–52.8%) n = 8,682,400 |

| 2013 | 27.6% (27.2–27.9%) n = 4,599,075 | 19.2% (18.9–19.5%) n = 3,201,882 | 42.2% (41.8–42.6%) n = 7,045,058 | 11.0% (10.7–11.4%) n = 1,843,362 | 47.4% (47.0–47.7%) n = 7,904,803 | 52.6% (52.3–53.0%) n = 8,784,574 | |

| 2015 | 26.9% (26.6–27.2%) n = 4,564,618 | 19.2% (18.9–19.7%) n = 3,271,371 | 42.1% (41.8–42.4%) n = 7,143,977 | 11.7% (11.4–12.0%) n = 1,990,095 | 47.3% (47.1–47.5%) n = 8,026,020 | 52.7% (52.5–53.0%) n = 8,944,041 | |

| 2017 | 25.3% (24.9–25.7%) n = 4,266,281 | 18.7% (18.4–19.0%) n = 3,151,050 | 42.8% (42.5–43.1%) n = 7,213,101 | 13.1% (12.8–13.5%) n = 2,213,039 | 47.5% (47.2–47.7%) n = 7,995,319 | 52.5% (52.3–52.8%) n = 8,848,152 | |

| Settled migrants | 2011 | 19.9% (15.9–24.7%) n = 31,326 | 34.1% (29.0–39.6%) n = 53,518 | 42.6% (36.6–48.8%) n = 66,935 | 3.4% (2.3–4.9%) n = 5348 | 42.1% (38.2–46.2%) n = 66,225 | 57.9% (53.8–61.8%) n = 90,902 |

| 2013 | 16.8% (14.3–19.6%) n = 35,918 | 31.7% (27.9–35.7%) n = 67,813 | 47.3% (43.0–51.7%) n = 101,364 | 4.2% (3.1–5.8%) n = 9022 | 43.3% (39.1–47.9%) n = 92,685 | 56.7% (52.4–60.9%) n = 121,432 | |

| 2015 | 17.0% (14.5–19.7%) n = 46,111 | 33.1% (29.3–37.1%) n= 89,908 | 47.5% (43.3–51.7%) n = 128,985 | 2.5% (1.9–3.3%) n = 6779 | 47.8% (44.8–50.8%) n = 129,893 | 52.2% (49.2–55.2%) n = 141,890 | |

| 2017 | 15.5% (13.4–17.9%) n = 34,912 | 29.0% (26.1–32.2%) n = 125,471 | 52.4% (48.5–56.3%) n = 65,131 | 3.0% (2.2–4.1%) n = 26,658 | 44.6% (42.1–47.2%) n = 132,185 | 55.4% (52.8–57.9%) n = 163,937 | |

| Emerging migrants | 2011 | 17.9% (13.0–24.2%) n = 4992 | 39.6% (31.5–48.2%) n = 11,036 | 42.1% (33.9–50.8%) n = 11,732 | 0.4% (0.1–1.6%) n = 107 | 47.1% (64–58.1%) n = 13,137 | 52.9% (41.9–63.6%) n = 14,730 |

| 2013 | 13.8% (10.4–18.2%) n = 8662 | 32.7% (26.8–39.1%) n = 20,445 | 52.7% (47.1–58.2%) n = 32,961 | 0.8% (0.2–2.7%) n = 510 | 48.9% (44.8–53.0%) n = 30,598 | 51.1% (47.0–55.2%) n = 31,980 | |

| 2015 | 21.1% (17.4–25.2%) n = 22,812 | 30.1% (25.0–35.9%) n = 32,665 | 47.3% (43.9–50.8%) n = 51,315 | 1.5% (0.8–2.9%) n = 1603 | 48.4% (45.0–51.8%) n = 52,458 | 51.6% (48.2–55.0%) n = 55,937 | |

| 2017 | 16.4% (14.5–18.4%) n = 63,848 | 44.9% (39.6–50.4%) n = 175,522 | 37.9% (33.1–43.0%) n = 148,003 | 0.7% (0.4–1.6%) n = 3115 | 51.0% (47.7–54.4%) n = 199,332 | 49.0% (45.6–52.3%) n = 191,156 | |

| Migrants from other countries | 2011 | 22.7% (15.9–31.4%) n = 9090 | 24.6% (19.0–31.3%) n = 14,607 | 42.9% (34.2–52.0%) n = 6047 | 9.7% (6.5–14.3%) n = 1927 | 50.1% (43.0–57.3%) n = 29,516 | 49.9% (42.7–57.0%) n = 29,368 |

| 2013 | 25.1% (11.6–46.0%) n = 19,522 | 19.3% (14.0–26.0%) n = 15,014 | 45.4% (33.8–57.6%) n = 35,386 | 10.2% (6.9–14.9%) n = 7964 | 46.3% (34.4–58.7%) n = 36,070 | 53.7% (41.3–65.6%) n = 41,816 | |

| 2015 | 18.8% (15.5–22.6%) n = 16,017 | 23.4% (18.3–29.3%) n = 19,885 | 49.3% (43.7–55.0%) n = 41,998 | 8.5% (6.0–11.9%) n = 7241 | 48.5% (43.5–53.5%) n = 41,265 | 51.5% (46.5–56.5%) n = 43,876 | |

| 2017 | 12.6% (9.7–16.3%) n = 11,455 | 25.8% (21.1–31.1%) n = 23,414 | 50.7% (45.7–55.7%) n = 46,045 | 10.9% (8.6–13.7%) n = 9883 | 51.2% (47.0–55.4%) n = 46,522 | 48.8% (44.6–53.0%) n = 44,275 | |

| None (Particular) | Fonasa A.B | Fonasa C.D | Fonasa Does Not Know | Isapre | Other | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chilean-born | 2011 | 2.40% (2.2–2.6%) n = 397,011 | 59.34% (58.1–61.0%) n = 9,837,628 | 18.38% (17.6–19.2%) n = 3,046,172 | 3.58% (3.1–4.1%) n = 593,233 | 12.80% (11.9–13.8%) n = 2,122,542 | 2.48% (2.2–2.7%) n = 410,224 |

| 2013 | 2.53% (2.3–2.8%) n = 422,224 | 53.13% (52.2–54.1%) n = 8,867,072 | 21.02% (20.5–21.6%) n = 3,508,536 | 4.44% (4.2–4.7%) n = 740,903 | 14.15% (13.4–15.0%) n = 2,361,099 | 3.00% (2.8–3.2%) n = 493,162 | |

| 2015 | 2.71% (2.6–2.8%) n = 459,799 | 50.71% (49.9–51.5%) n = 8,605,778 | 22.58% (22.2–23.0%) n = 3,832,521 | 4.43% (4.2–4.7%) n = 750,845 | 14.98% (14.3–15.7%) n = 2,542,521 | 2.90% (2.6–3.2%) n = 492,232 | |

| 2017 | 2.25% (2.1–2.4%) n = 378,239 | 51.21% (50.4–52.0%) n = 8.626,019 | 22.24% (21.8–22.7%) n = 3,746,202 | 5.20% (4.9–5.5%) n = 875,915 | 14.37% (13.6–15.1%) n = 2,419,529 | 2.83% (2.6–3.1%) n = 476,681 | |

| Settled migrants | 2011 | 11.43% (8.7–15.0%) n = 17,957 | 53.78% (47.9–59.6%) n = 84,498 | 19.15% (14.4–25.0%) n = 30,083 | 3.42% (2.1–5.6%) n = 5371 | 8.97% (5.8–13.6%) n = 14,092 | 1.287% (0.7–2.4%) n = 2022 |

| 2013 | 8.50% (6.5–11.0%) n = 18,207 | 45.36% (39.7–51.1%) n = 97,112 | 25.87% (21.0–31.4%) n = 55,392 | 7.24% (4.8–10.8%) n = 15,508 | 11.33% (8.3–15.3%) n = 24,263 | 0.723% (0.4–1.2%) n = 1547 | |

| 2015 | 14.66% (10.8–19.5%) n = 39,839 | 40.17% (34.5–46.1%) n = 109,185 | 21.33% (17.3–26.0%) n = 57,981 | 8.52% (6.5–11.2%) n = 23,157 | 12.73% (9.0–17.7%) n = 34,603 | 1.07% (0.7–1.7%) n = 2910 | |

| 2017 | 11.79% (10.1–13.7%) n = 34,912 | 42.37% (38.2–46.7%) n = 125,471 | 21.99% (19.4–24.8%) n = 65,131 | 9.00% (7.2–11.3%) n = 26,658 | 10.47% (7.7–14.1%) n = 31,012 | 1.58% (0.9–2.7%) n = 4681 | |

| Emerging migrants | 2011 | 25.31% (13.7–42.1%) n = 7052 | 26.30% (17.8–37.1%) n = 7328 | 16.96% (10.1–27.1%) n = 4725 | 5.83% (2.7–12.0%) n = 1624 | 23.61% (12.3–40.5%) n = 6579 | 0.24% (0.1–0.8%) n = 67 |

| 2013 | 12.85% (8.8–18.4%) n = 8041 | 28.67% (20.2–39.0%) n = 17,939 | 17.41% (12.0–24.5%) n = 10,892 | 11.18% (6.2–19.3%) n = 6995 | 23.09% (15.4–33.2%) n = 14,451 | 0.98% (0.3–3.2%) n = 612 | |

| 2015 | 21.06% (15.1–28.5%) n = 22,830 | 32.79% (25.6–40.9%) n = 35,545 | 18.59% (13.4–25.2%) n = 20,150 | 7.19% (4.6–11.0%) n = 7792 | 12.05% (8.4–17.0%) n = 13,066 | 5.22% (1.9–13.9%) n = 5662 | |

| 2017 | 19.27% (15.3– 24.1%) n = 75,261 | 32.07% (26.9–37.7%) n = 125,215 | 22.53% (17.3–28.9%) n = 87,975 | 9.93% (6.4–15.1%) n = 38,755 | 12.24% (8.7–16.9%) n = 47,779 | 0.96% (0.4–2.1%) n = 3730 | |

| Migrants from other countries | 2011 | 15.44% (9.0–25.3%) n = 9090 | 24.81% (16.9–34.9%) n = 14,607 | 10.27% (6.6–15.6%) n = 6047 | 3.27% (1.7–6.3%) n = 1927 | 41.62% (33.1–50.7%) n = 24,506 | 3.77% (1.9–7.5%) n = 2218 |

| 2013 | 6.79% (4.2–10.7%) n = 5287 | 32.68% (18.7–50.6%) n = 25,456 | 13.30% (9.0–19.3%) n = 10,361 | 5.06% (2.7–9.4%) n = 3944 | 32.59% (23.6–43.1%) n = 25,381 | 7.61% (4.4–12.9%) n = 5929 | |

| 2015 | 12.22% (7.6–19.1%) n = 10,402 | 19.64% (16.1–23.7%) n = 16,720 | 16.11% (10.9–23.2%) n = 13,716 | 5.04% (2.9–8.6%) n = 4293 | 40.01% (34.0–46.3%) n = 34,064 | 5.68% (3.5–9.0%) n = 4837 | |

| 2017 | 14.14% (9.7–20.1%) n = 12,840 | 27.09% (21.9–33.0%) n = 24,592 | 10.02% (7.8–12.7%) n = 9094 | 3.81% (2.6–5.6%) n = 3462 | 38.82% (33.0–44.9%) n = 35,248 | 4.37% (2.6–7.5%) n = 3967 |

| Men | Women | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) | (f) | (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) | (f) | ||

| Chilean-born | 2011 | 243,223 | 7,181,391 | 70,500 | 14,757 | 195,966 | 57,458 | 153,788 | 8,030,436 | 82,679 | 18,279 | 285,396 | 98,666 |

| 3.1% | 91.0% | 7.9% | 20.9% | 18.0% | 29.3% | 1.8% | 92.5% | 6.8% | 22.1% | 16.1% | 34.6% | ||

| 2013 | 260,277 | 2,960,170 | 100,128 | 13,334 | 186,824 | 42,652 | 161,947 | 2,277,091 | 123,701 | 16,667 | 262,618 | 80,826 | |

| 3.3% | 84.8% | 7.6% | 13.3% | 16.0% | 22.8% | 1.8% | 89.4% | 6.5% | 13.5% | 13.9% | 30.8% | ||

| 2015 | 274,672 | 2,878,251 | 116,688 | 14,388 | 207,285 | 45,427 | 185,127 | 2,371,869 | 135,587 | 21,659 | 281,557 | 64,632 | |

| 3.4% | 80.8% | 7.6% | 12.3% | 17.2% | 21.9% | 2.1% | 85.9% | 6.0% | 16.0% | 14.4% | 23.0% | ||

| 2017 | 231,957 | 2,761,155 | 91,342 | 11,219 | 190,963 | 37,484 | 146,282 | 2,490,384 | 112,188 | 15,331 | 259,435 | 55,801 | |

| 2.9% | 80.0% | 6.6% | 12.3% | 15.3% | 19.6% | 1.7% | 83.9% | 5.7% | 13.7% | 13.4% | 21.5% | ||

| Settled migrants | 2011 | 8766 | 60,451 | 177 | 39 | 322 | 0 | 9191 | 84,066 | 581 | 88 | 2518 | 503 |

| 13.2% | 91.3% | 3.8% | 22.0% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 10.1% | 92.5% | 9.7% | 15.1% | 35.2% | 20.0% | ||

| 2013 | 9717 | 39,563 | 554 | 16 | 985 | 126 | 8490 | 30,726 | 2100 | 295 | 1648 | 75 | |

| 10.5% | 84.5% | 6.6% | 2.9% | 21.3% | 12.8% | 7.0% | 89.9% | 8.5% | 14.0% | 14.2% | 4.6% | ||

| 2015 | 19,748 | 59,198 | 2199 | 120 | 2602 | 346 | 20,091 | 47,263 | 2728 | 377 | 2520 | 989 | |

| 15.2% | 84.3% | 9.9% | 5.5% | 36.0% | 13.3% | 14.2% | 89.1% | 11.2% | 13.8% | 16.8% | 39.2% | ||

| 2017 | 17,345 | 63,263 | 1516 | 309 | 4957 | 1270 | 17,567 | 53,023 | 2430 | 845 | 2807 | 822 | |

| 13.1% | 84.0% | 9.0% | 20.4% | 54.4% | 25.6% | 10.7% | 88.0% | 8.2% | 34.8% | 22.9% | 29.3% | ||

| Emerging migrants | 2011 | 4045 | 10,751 | 69 | 19 | 17 | 0 | 3007 | 11,885 | 36 | 0 | 640 | 0 |

| 30.8% | 81.8% | 13.7% | 27.5% | 17.5% | 0.0% | 20.4% | 80.7% | 1.1% | 0 | 71.0% | 0.0% | ||

| 2013 | 3814 | 15,168 | 197 | 0 | 660 | 0 | 4227 | 7072 | 1076 | 860 | 806 | 384 | |

| 12.5% | 83.9% | 6.0% | 0.0% | 75.5% | 0.0% | 13.2% | 82.6% | 21.4% | 79.9% | 26.3% | 47.6% | ||

| 2015 | 10,397 | 27,324 | 837 | 0 | 650 | 505 | 12,433 | 12,953 | 1341 | 659 | 2089 | 644 | |

| 19.8% | 87.3% | 12.4% | 0.0% | 48.3% | 77.7% | 22.2% | 78.3% | 18.0% | 49.1% | 39.8% | 30.8% | ||

| 2017 | 37,353 | 99,335 | 2460 | 47 | 1896 | 902 | 37,908 | 59,598 | 2512 | 1027 | 2387 | 866 | |

| 18.7% | 82.9% | 9.5% | 1.9% | 45.6% | 47.6% | 19.8% | 87.5% | 9.6% | 40.9% | 43.8% | 36.3% | ||

| Migrants from other countries | 2011 | 5644 | 20,455 | 412 | 0 | 969 | 178 | 3446 | 24,378 | 1090 | 0 | 1773 | 37 |

| 19.1% | 69.3% | 15.1% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 18.4% | 11.7% | 83.0% | 22.2% | 0 | 48.6% | 2.1% | ||

| 2013 | 2307 | 10,999 | 207 | 0 | 1371 | 100 | 2980 | 6997 | 357 | 23 | 1424 | 371 | |

| 6.4% | 59.5% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 42.7% | 7.3% | 7.1% | 59.4% | 5.6% | 6.4% | 39.5% | 26.1% | ||

| 2015 | 5277 | 16,129 | 1177 | 0 | 2697 | 1003 | 5125 | 6374 | 725 | 53 | 1847 | 88 | |

| 12.8% | 65.6% | 14.8% | 0.0% | 48.8% | 37.2% | 11.7% | 56.2% | 8.0% | 7.3% | 36.5% | 4.8% | ||

| 2017 | 8178 | 18,948 | 980 | 58 | 2190 | 188 | 4662 | 8350 | 822 | 0 | 2641 | 1105 | |

| 17.6% | 66.2% | 12.4% | 5.9% | 43.7% | 8.6% | 10.5% | 58.0% | 8.4% | 0.0% | 50.7% | 41.8% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oyarte, M.; Cabieses, B.; Rada, I.; Blukacz, A.; Espinoza, M.; Mezones-Holguin, E. Unequal Access and Use of Health Care Services among Settled Immigrants, Recent Immigrants, and Locals: A Comparative Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey in Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010741

Oyarte M, Cabieses B, Rada I, Blukacz A, Espinoza M, Mezones-Holguin E. Unequal Access and Use of Health Care Services among Settled Immigrants, Recent Immigrants, and Locals: A Comparative Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey in Chile. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010741

Chicago/Turabian StyleOyarte, Marcela, Baltica Cabieses, Isabel Rada, Alice Blukacz, Manuel Espinoza, and Edward Mezones-Holguin. 2023. "Unequal Access and Use of Health Care Services among Settled Immigrants, Recent Immigrants, and Locals: A Comparative Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey in Chile" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010741

APA StyleOyarte, M., Cabieses, B., Rada, I., Blukacz, A., Espinoza, M., & Mezones-Holguin, E. (2023). Unequal Access and Use of Health Care Services among Settled Immigrants, Recent Immigrants, and Locals: A Comparative Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey in Chile. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010741