Prevalence Rates of Depression and Anxiety among Young Rural and Urban Australians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Meta-Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

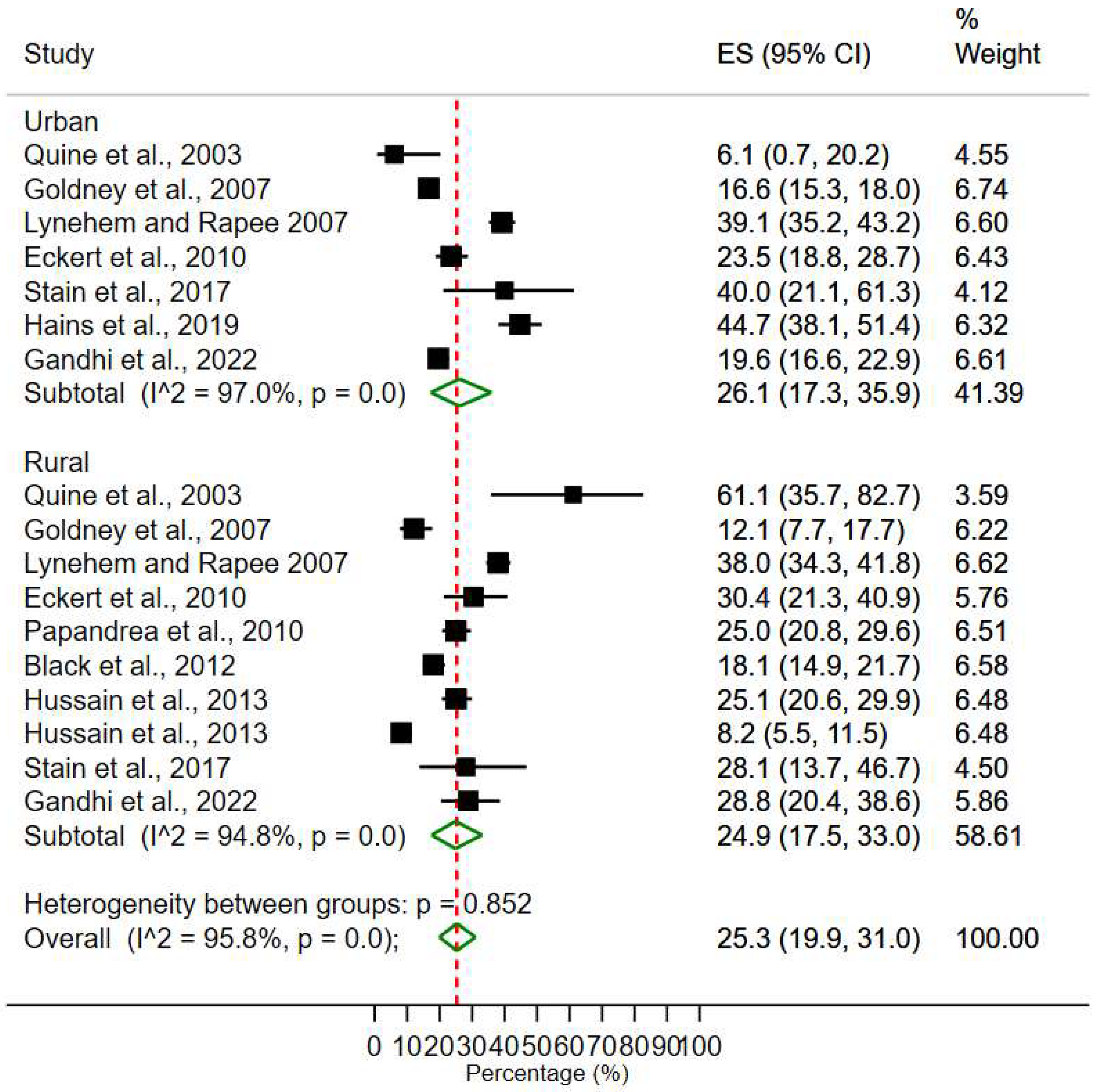

3.2. Studying Forest Plots

3.3. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety

3.4. Rural-Urban Areas Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

3.6. Rural-Urban Areas Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Disorders. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattani, S.; Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Mental Health. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Black Dog Institute. Facts & Figures about Mental Health. Available online: https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/1-facts_figures.pdf?sfvrsn=8 (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Australia 2018. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/abds-impact-and-causes-of-illness-and-death-in-aus/summary (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and Remote Health. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Smith, J.A.; Canuto, K.; Canuto, K.; Campbell, N.; Schmitt, D.; Bonson, J.; Smith, L.; Connolly, P.; Bonevski, B.; Rissel, C.; et al. Advancing health promotion in rural and remote Australia: Strategies for change. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 33, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Choi, J.-K. The longitudinal influences of adverse childhood experiences and positive childhood experiences at family, school. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, F.; Dykxhoorn, J.; Kirkbride, J.B. Urban-rural differences in major mental health conditions. In Mental Health and Illness in the City; Okkels, N., Kristiansen, C.B., Munk-Jørgensen, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanton, R.; Rebar, A.L.; Rosenbaum, S. Supporting better mental health services for rural Australians: Secondary analysis from the Australian National Social Survey. Aust. J. Rural Health 2020, 28, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Orom, H.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kiviniemi, M.T. Differences in rural and urban health information access and use. J. Rural Health 2019, 35, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spasojevic, N.; Vasilj, I.; Hrabac, B.; Celik, D. Rural urban differences in health care quality assessment. Mater. Socio-Med. 2015, 27, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ying, M.; Wang, S.; Bai, C.; Li, Y. Rural-urban differences in health outcomes, healthcare use, and expenditures among older adults under universal health insurance in China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disease Expenditure in Australia 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/health-welfare-expenditure/disease-expenditure-australia/contents/summary (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental Health: Prevalence and Impact. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Rajkumar, R.P. he correlates of government expenditure on mental health services: An analysis of data from 78 countries and regions. Cureus 2022, 14, e28284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headspace. Distress Levels on the Rise in Young People. Headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation. Available online: https://headspace.org.au/our-organisation/media-releases/distress-levels-on-the-rise-in-young-people/ (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Piper, E.S.; Bailey, E.P.; Lam, T.L.; Kneebone, I.I. Predictors of mental health literacy in older people. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 79, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kiely, M.K.; Brady, B.; Byles, J. Gender, mental health and ageing. Maturitas 2019, 129, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M.; Tripathi, A.; Deshmukh, D.; Gaur, M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression. Ind. J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, S223–S229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Hadwin, A. The roles of sex and gender in child and adolescent mental health. JCPP Adv. 2022, 2, e12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, A.; Weber, K.; Baertschi, M.; Andreas, S.; Volkert, J.; Dehoust, M.C.; Sehner, S.; Suling, A.; Wegscheider, K.; Ausín, B.; et al. Anxiety Disorders in Old Age: Psychiatric Comorbidities, Quality of Life, and Prevalence According to Age, Gender, and Country. Am. J. Geriatr Psychiatry 2018, 26, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, R.; Szilagyi, M.; Perrin, J.M. Epidemic rates of child and adolescent mental health disorders require an urgent response. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2022056611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, H.; Mohaqeqi, K.S.H.; Rafiey, H.; Vameghi, M.; Forouzan, A.S.; Rezaei, M. A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors of depression among Iranian adolescents. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCarthy, C. Anxiety in Teens Is Rising: What’s Going on? Available online: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/emotional-problems/Pages/Anxiety-Disorders.aspx (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Mission Australia. Youth Survey Report 2021. Available online: https://www.missionaustralia.com.au (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Risk Factors to Health. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/risk-factors/risk-factors-to-health/contents/risk-factors-and-disease-burden (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Eckert, K.A.; Kutek, S.M.; Dunn, K.I.; Air, T.M.; Goldney, R.D. Changes in depression-related mental health literacy in young men from rural and urban South Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2010, 18, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macphee, A.R.; Andrews, J.J. Risk factors for depression in early adolescence. Adolescence 2006, 41, 435–466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Renae McGee, T.; Scott, J.G.; McGrath, J.J.; Williams, G.M.; O’Callaghan, M.; Bor, W.; Najman, J.M. Young adult problem behaviour outcomes of adolescent bullying. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2011, 3, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Better Health: Victoria State Government. Young People (13–19). Available online: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/healthyliving/young-people-13-19 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Rao, U.; Chen, L.-A. Characteristics, correlates, and outcomes of childhood and adolescent depressive disorders. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, P.; Leach, L. Early Onset of Distress Disorders and High-School Dropout: Prospective Evidence From a National Cohort of Australian Adolescents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.J.; Handley, T.; Powell, N.; Read, D.; Inder, K.J.; Perkins, D.; Brew, B.K. Suicide in rural Australia: A retrospective study of mental health problems, health-seeking and service utilisation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 0245271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.; Dear, B.F.; Gandy, M.; Fogliati, V.J.; Kayrouz, R.; Sheehan, J.; Rapee, R.M.; Titov, N. Exploring the efficacy and acceptability of Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for young adults with anxiety and depression: An open trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.R. The Acceptability of Using Moodgym to Treat Depression in Adolescents: A pilot Study. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 2016. Available online: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=11947&context=etd (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Newcombe, P.A.; Dunn, T.L.; Casey, L.M.; Sheffield, J.K.; Petsky, H.; Anderson-James, S.; Chang, A.B. Breathe Easier Online: Evaluation of a randomized controlled pilot trial of an Internet-based intervention to improve well-being in children and adolescents with a chronic respiratory condition. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ralph, A.; Sanders, M.R. Preliminary evaluation of the Group Teen Triple P program for parents of teenagers making the transition to high school. Aust. E-J. Adv. Ment. Health 2003, 2, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H.; Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy as a function of remoteness of residence: An Australian national study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffiths, K.M.; Crisp, D.; Christensen, H.; Mackinnon, A.J.; Bennet, K. The ANU WellBeing study: A protocol for a quasi-factorial randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of an Internet support group and an automated Internet intervention for depression. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernan, A.; Philpot, B.; Edmonds, A.; Reddy, P. Healthy minds for country youth: Help-seeking for depression among rural adolescents. Aust. J. Rural Health 2010, 18, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.J.; Rickwood, D.; Deane, F.P. Depressive symptoms and help-seeking intentions in young people. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.J.; Deane, F.P. Help-negation and suicidal ideation: The role of depression, anxiety and hopelessness. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, K.A.; Wilkinson, D.; Taylor, A.W.; Stewart, S.; Tucker, G.R. A population view of mental illness in South Australia: Broader issues than location. Rural Remote Health 2006, 6, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldney, R.D.; Taylor, A.W.; Bain, M.A. Depression and remoteness from health services in South Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2007, 15, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.M.; Dustan, A.D. Mental Health Literacy of Australian Rural Adolescents: An Analysis Using Vignettes and Short Films. Aust. Psychol. 2013, 48, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.Y.; Wong, D.F.K.; Cheng, C.W.; Pan, S.M. Mental health literacy, stigma and perception of causation of mental illness among Chinese people in Taiwan. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, 2020–2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Blau, A.; Byrd, J.; Piper, G. Far from Care: How Your Postcode Can Influence Whether You Need Help—And If You’ll Get It. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-08/covid-mental-health-system-medicare-inequality/12512378 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. -Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaga, V.N.; Arbyn, M.; Aerts, M. Metaprop: A Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch. Public Health 2014, 72, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, M.F.; Tukey, J.W. Transformations Related to the Angular and the Square Root. Ann. Math. Stat. 1950, 21, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey, S.G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhandari, P. What is Effect Size and Why Does It Matter? Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/effect-size/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Black, G.; Roberts, R.M.; Li-Leng, T. Depression in rural adolescents: Relationships with gender and availability of mental health services. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, E.; OGradey-Lee, M.; Jones, A.; Hudson, J.L. Receipt for evidence-based care for children and adolescents with anxiety in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2022, 56, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hains, A.; Janackovski, A.; Deane, F.P.; Rankin, K. Perceived burdensomeness predicts outcomes of short-term psychological treatment of young people at risk of suicide. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Guppy, M.; Robertson, S.; Temple, E. Physical and mental health perspectives of first year undergraduate rural university students. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lynehem, J.H.; Rapee, M.R. Childhood anxiety in rural and urban areas: Presentation, impact and help seeking. Aust. J. Psychol. 2007, 59, 59–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandrea, K.; Winefield, H.; Livingstone, A. Oiling a neglected wheel: An investigation of adolescent internalising problems in rural South Australia. Rural Remote Health 2010, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quine, S.; Bernard, D.; Booth, M.; Kang, M.; Usherwood, T.; Alperstein, G.; Bennett, D. Health and access issues among Australian adolescents: A rural-urban comparison. Rural Remote Health 2003, 3, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stain, H.J.; Halpin, S.A.; Baker, A.L.; Startup, M.; Carr, V.J.; Schall, U.; Crittenden, K.; Clark, V.; Lewin, T.J.; Bucci, S. Impact of rurality and substance use on young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 12, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, J.R.; Norvell, D.C.; Chapman, J.R. Seeing the Forest by Looking at the Trees: How to Interpret a Meta-Analysis Forest Plot. Glob. Spine J. 2021, 11, 614–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantley, N. How to Read A Forest Plot. Available online: https://s4be.cochrane.org/blog/2016/07/11/tutorial-read-forest-plot/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Page, A.N.; Swannell, S.; Martin, G.; Hollingworth, S.; Hickie, I.B.; Hall, W.D. Sociodemographic correlates of antidepressant utilisation in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslau, J.; Marshall, G.N.; Pincus, H.A.; Brown, R.A. Are mental disorders more common in urban than rural areas of the United States? J. Psych. Res. 2014, 56, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, Q.; Delprino, R.P. Psychological health among Chinese college students: A rural/urban comparison. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2017, 29, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.; Judd, F.; Jackson, H.; Murray, G.; Humphreys, J.; Hodgins, G.A. Does one size really fit all? Why the mental health of rural Australians requires further research. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2002, 10, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, T.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Dear, K.B.G. Suicide and mental health in rural, remote and metropolitan areas in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2004, 181, S10–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L. Rural-urban differences in the prevalence of major depression and associated impairment. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, S.; Ostry, A.; Callaghan, K.; Hershler, R.; Chen, L.; D’Angiulli, A.; Hertzman, C. Rural-urban migration patterns and mental health diagnoses of adolescents and young adults in British Columbia, Canada: A case-control study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2010, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romans, S.; Cohen, M.; Forte, T. Rates of depression and anxiety in urban and rural Canada. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E.; Verduyn, P.; Sheppes, G.; Costello, C.K.; Jonides, J.; Ybarra, O. Social media and well-being: Pitfalls, progress, and next steps. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, S.; Shu, M. Social media activities, emotion regulation strategies, and their interactions on people’smental health in COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, M.L.; Leung, W.K.; Aw, E.C.X.; Koay, K.Y. “I follow what you post!”: The role of social media influencers’content characteristics in consumers’ online brand-relatedactivities (COBRAs). J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, C.; Rubio, J.; Wall, M.; Wang, S.; Jiu, C.J.; Kendler, K.S. Risk factors for anxiety disorders: Common and specific effects in a national sample. Depress Anxiety 2014, 31, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, W. Adolescent depression: National trends, risk factors, and healthcare disparities. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galambos, N.L.; Leadbeater, B.J.; Barker, E.T. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004, 28, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluja, G.; Iachan, R.; Scheidt, P.C.; Overpeck, M.D.; Sun, W.; Giedd, J.N. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handley, T.; Rich, J.; Davies, K.; Lewin, T.; Kelly, B. The Challenges of Predicting Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviours in a Sample of Rural Australians with Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jamieson, L.M.; Paradies, Y.C.; Gunthorpe, W.; Cairney, S.J.; Sayers, S.M. Oral health and social and emotional well-being in a birth cohort of Aboriginal Australian young adults. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Communities in Rural Australia. Available online: https://www.ranzcp.org/practice-education/rural-psychiatry/about-rural-psychiatry/communities-in-rural-australia (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Li, Y.; Scherer, N.; Felix, L.; Kuper, H. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lynehem and Rapee, 2007 [63] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Hussain et al., 2013 [62] | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Papandrea et al., 2010 [64] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Stain et al., 2017 [66] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 |

| Quine et al., 2003 [65] | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | 7 |

| Black et al., 2012 [59] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 |

| Goldney et al., 2007 [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Eckert et al., 2010 [28] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Hains et al., 2019 [61] | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Gandhi et al., 2022 [60] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 |

| Total Y | 9 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 | |

| Total N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Total U | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Y% | 90% | 80% | 70% | 100% | 80% | 100% | 100% | 90% | 70% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kasturi, S.; Oguoma, V.M.; Grant, J.B.; Niyonsenga, T.; Mohanty, I. Prevalence Rates of Depression and Anxiety among Young Rural and Urban Australians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010800

Kasturi S, Oguoma VM, Grant JB, Niyonsenga T, Mohanty I. Prevalence Rates of Depression and Anxiety among Young Rural and Urban Australians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010800

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasturi, Sushmitha, Victor M. Oguoma, Janie Busby Grant, Theo Niyonsenga, and Itismita Mohanty. 2023. "Prevalence Rates of Depression and Anxiety among Young Rural and Urban Australians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010800