Isolated Sphenoid Sinus Disease in Children

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wyllie, J.W., 3rd; Kern, E.B.; Djalilian, M. Isolated sphenoid sinus lesions. Laryngoscope 1973, 83, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.H.; Sethi, D.S. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: Differential diagnosis and management. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 19, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fireman, P. Diagnosis of sinusitis in children: Emphasis on the history and physical examination. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1992, 90 Pt 2, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseglia, G.L.; Pagella, F.; Licari, A.; Scaramuzza, C.; Marseglia, A.; Leone, M.; Ciprandi, G. Acute isolated sphenoid sinusitis in children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 70, 2027–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elden, L.M.; Reinders, M.E.; Kazahaya, K.; Tom, L.W. Management of isolated sphenoid sinus disease in children: A surgical perspective. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 75, 1594–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilony, D.; Talmi, Y.P.; Bedrin, L.; Ben-Shosan, Y.; Kronenberg, J. The clinical behavior of isolated sphenoid sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007, 136, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlman, S.J.; Lawson, W.; Biller, H.F.; Friedman, W.H.; Potter, G.D. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease. Laryngoscope 1989, 99 Pt 1, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothfield, R.E.; de Vries, E.J.; Rueger, R.G. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease. Head Neck 1991, 13, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hnatuk, L.A.; Macdonald, R.E.; Papsin, B.C. Isolated sphenoid sinusitis: The Toronto Hospital for Sick Children experience and review of the literature. J. Otolaryngol. 1994, 23, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gilain, L.; Aidan, D.; Coste, A.; Peynegre, R. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery for isolated sphenoid sinus disease. Head Neck 1994, 16, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadar, T.; Yaniv, E.; Shvero, J. Isolated sphenoid sinus changes- history, CT and endoscopic finding. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1996, 110, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, W.; Reino, A.J. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: An analysis of 132 cases. Laryngoscope 1997, 107 Pt 1, 1590–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, D.S. Isolated sphenoid lesions: Diagnosis and management. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1999, 120, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.M.; Kanoh, N.; Dai, C.F.; Chi, F.L.; Kutler, D.I.; Tian, X.I. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: An analysis of 122 cases. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2002, 111, 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.K.; Ong, Y.K. Acute isolated sphenoid sinusitis. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2004, 33, 656–659. [Google Scholar]

- Soon, S.R.; Lim, C.M.; Singh, H.; Sethi, D.S. Sphenoid sinus mucocele: 10 cases and literature review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2010, 124, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnuovo, P.; Pagella, F.; Semino, L.; De Bernardi, F.; Delù, G. Endoscopic treatment of the isolated sphenoid sinus lesions. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005, 262, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimi-Cohen, Y.; Amir, J.; Zeharia, A.; Danziger, Y.; Ziv, N.; Mimouni, M. Isolated sphenoidal sinusitis in children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1999, 158, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proetz, A.W. Operation on the sphenoid. Trans. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 1949, 53, 538–545. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.H.; Fang, S.Y.; Ho, H.C. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: Analysis of 11 cases. Tzu. Chi. Med. J. 2009, 21, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, P.P.; Ge, W.T.; Ni, X.; Tang, L.X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.J.; Sun, J.H. Endoscopic Treatment of Isolated Sphenoid Sinus Disease in Children. Ear Nose Throat J. 2019, 98, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Massoubre, J.; Saroul, N.; Vokwely, J.E.; Lietin, B.; Mom, T.; Gilain, L. Results of transnasal transostial sphenoidotomy in 79 cases of chronic sphenoid sinusitis. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2016, 133, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, H. The sphenoid sinus, the neglected nasal sinus. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1978, 104, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakmak, O.; Shohet, M.R.; Kern, E.B. Isolated sphenoid sinus lesions. Am. J. Rhinol. 2000, 14, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, Y.A.; Al-Madani, A.; El-Daly, A.; Gaafar, A. Isolated sphenoid sinus pathology: Spectrum of diagnostic and treatment modalities. Auris Nasus Larynx 2008, 35, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.; Batra, P.S.; Fakhri, S.; Citardi, M.J.; Lanza, D.C. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: Etiology and management. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2005, 133, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caimmi, D.; Caimmi, S.; Labò, E.; Marseglia, A.; Pagella, F.; Castellazzi, A.M.; Marseglia, G.L. Acute isolated sphenoid sinusitis in children. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2011, 25, e200–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, P.A.; Bluestone, C.D.; Gordts, F.; Lusk, R.P.; Otten, F.W.; Goossens, H.; Scadding, G.K.; Takahashi, H.; Van Buchem, F.L.; Van Cauwenberge, P.; et al. Management of rhinosinusitis in children: Consensus meeting, Brussels, Belgium, September 13, 1996. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998, 124, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58 (Suppl. S29), 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, W.J.; Finegersh, A.; Jafari, A.; Panuganti, B.; Coffey, C.S.; DeConde, A.; Husseman, J. Isolated sphenoid sinus opacifications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Forum. Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Xiang, H.; Huang, X.F.; Chen, B. Clinical Analysis of Sphenoid Sinus Mucocele With Initial Neurological Symptoms. Headache 2019, 59, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay-Davies, I.; Buchanan, M.A.; Prinsley, P.R. An unusual headache: Sphenoiditis in children and adolescents. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 75, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.S. Sinus headaches: Avoiding over- and mis-diagnosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009, 9, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ada, M.; Kaytaz, A.; Tuskan, K.; Güvenç, M.G.; Selçuk, H. Isolated sphenoid sinusitis presenting with unilateral VIth nerve palsy. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2004, 68, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, L.; Yang, B.; Subramanian, P.S. Clinical features of visual disturbances secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory diseases. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017, 17, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holt, G.R.; Standefer, J.A.; Brown, W.E., Jr.; Gates, G.A. Infectious diseases of the sphenoid sinus. Laryngoscope 1984, 94, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Khan, N. Isolated sphenoid sinusitis presenting as blindness. Ear Nose Throat. 2010, 89, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.; Wang, D.; Yu, H. Isolated sphenoid fungal sinusitis and vision loss: The case for early intervention. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2009, 123, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, T.J.; Smith, T.L.; Smith, M.M.; Loehrl, T.A. Evaluation and surgical management of isolated sphenoid sinus disease. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002, 128, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Socher, J.A.; Cassano, M.; Filheiro, C.A.; Cassano, P.; Felippu, A. Diagnosis and treatment of isolated sphenoid sinus disease: A review of 109 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008, 128, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.G.; Jones, N.S. The role of nasal endoscopy in outpatient management. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1998, 23, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.T.; Butler, I.J. Sphenoid sinusitis masquerading as migraine headaches in children. J. Child Neurol. 2001, 16, 882–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postma, G.N.; Chole, R.A.; Nemzek, W.R. Reversible blindness secondary to acute sphenoid sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1995, 112, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, W.R.; Khan, A.; Laws, E.R., Jr. Transseptal approaches for pituitary surgery. Laryngoscope 1990, 100, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, W.E. Endoscopic transpterygoid approach to the lateral sphenoid recess: Surgical approach and clinical experience. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2005, 133, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockbank, M.J.; Brookes, G.B. The sphenoiditis spectrum. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1991, 16, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzawi, S.; Shahrizal, T.; Prepageran, N.; Pailoor, J. Isolated sphenoid sinus lesion: A diagnostic dilemma. Qatar Med. J. 2014, 16, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Olina, M.; Quaglia, P.; Stangalini, V.; Guglielmetti, C.; Binotti, M.; Pia, F.; Bona, G. Acute complicated sphenoiditis in childhood. Case report and literature review. Minerva Pediatr. 2002, 54, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

| Sex | Age (Years) | Dominating Symptom | Imaging | Surgical Approach | Pathology | Recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 11 | Dizziness | CT | TN (no) | Lipoma/L | N/A |

| 2 | F | 8 | Headache | CT | TN (no) | Mucocele/R | Y |

| 3 | F | 17 | Headache | CT | TN (f) + SPL | Osteoma/L | Y |

| 4 | M | 8.5 | Diplopia + Headache | MRI CT | TN (f) | Fibrous dysplasia | except headache |

| 5 | F | 11 | Headache | MRI CT | TN (f) | CRSsNP/L | N |

| 6 | F | 7.5 | Headache | CT | TN (no) | CRSsNP/R | Y |

| 7 | M | 11 | Nasal obstruction | CT | TN (no) | Sphenochoanal polyp/R | Y |

| 8 | F | 17.5 | Headache | CT | TN (no) | CRSsNP/L | Y |

| 9 | F | 7 | Radiological findings | MRI CT | TN (f) | ALL | N/A |

| 10 | F | 9 | Headache | CT | TN (f) | CRSsNP/R | N |

| 11 | M | 12 | Headache | CT | TN (f) | CRSsNP/L | Y |

| 12 | F | 12.5 | Headache | CT | TN (no) | CRSsNP/L | Y |

| 13 | F | 15.5 | Headache + nasal congestion | CT | TS | CRSsNP/L | Y |

| 14 | M | 17 | Headache | CT | TN (f) + SPL | CRSsNP/R | Y |

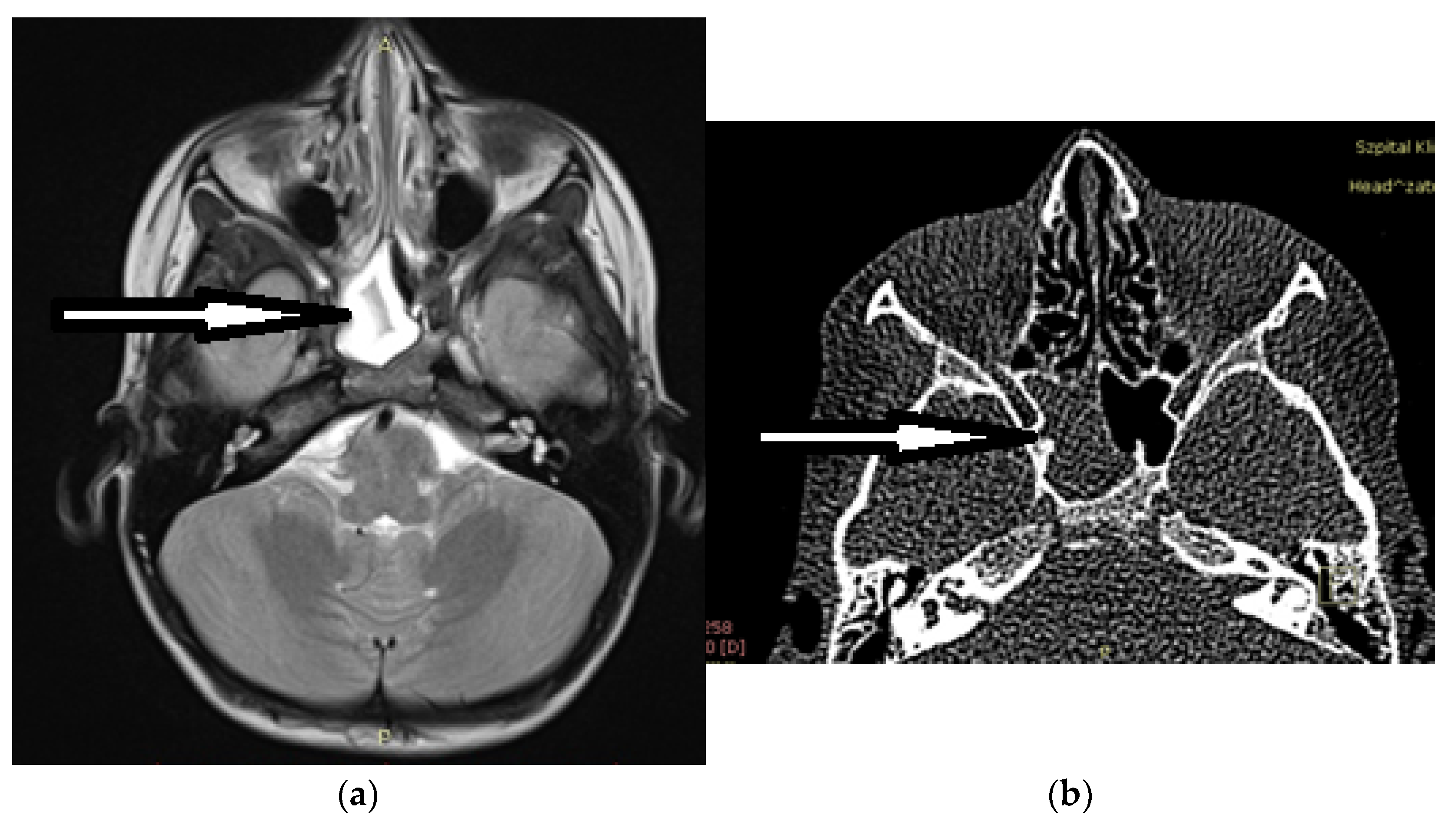

| 15 | M | 15 | Visual acuity disturbances | MRI | TS | Mucocele/R | Y |

| 16 | F | 17 | Headache | CT | TS | CRSsNP/L | Y |

| 17 | M | 10 | Headache | CT | TN (f) | Mucocele/R | Y |

| 18 | F | 5.5 | Diplopia | MRI CT | TN (no) | CRSsNP/R | Y |

| 19 | M | 13.5 | Headache | CT | TS | CRSsNP/R | N |

| 20 | M | 5.5 | Visual acuity disturbances + Diplopia + headache | MRI CT | TN (f) | CRSsNP/L | except headache |

| 21 | M | 12.5 | Headache | CT | TN (f) | Mucocele/L | Y |

| 22 | F | 16 | Headache | CT | TN (f) | CRSsNP/L | Y |

| 23 | F | 12 | Headache + papilloedema | MRI CT | TN (no) | CRSsNP/L | N |

| 24 | M | 12 | Headache | MRI CT | TN(f) | Mucocele/L | Y |

| 25 | F | 17 | Radiological findings | CT | TN (no) | Well differentiated chondrosarcoma G1 | N/A |

| 26 | M | 14 | Headache | CT | TN (no) | CRSsNP/L + R | Y |

| 27 | F | 14.5 | Headache | CT | TN (no) | Mucocele/R | Y |

| 28 | M | 11.5 | Headache | CT | TN (f) | CRSsNP/L | Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kotowski, M.; Szydlowski, J. Isolated Sphenoid Sinus Disease in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010847

Kotowski M, Szydlowski J. Isolated Sphenoid Sinus Disease in Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010847

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotowski, Michal, and Jaroslaw Szydlowski. 2023. "Isolated Sphenoid Sinus Disease in Children" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010847

APA StyleKotowski, M., & Szydlowski, J. (2023). Isolated Sphenoid Sinus Disease in Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010847