A Situation-Specific Theory of End-of-Life Communication in Nursing Homes

Abstract

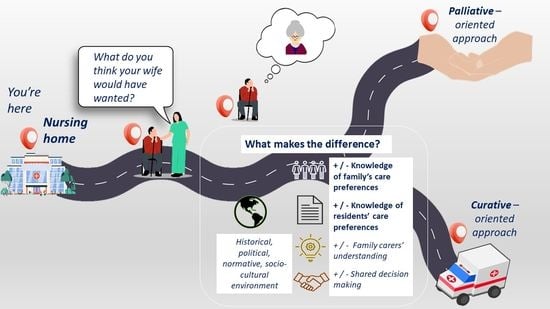

1. Introduction

Background

2. Methods

2.1. Instrumental Case Study

2.1.1. Study Design

2.1.2. Primary Study

2.1.3. Current Study

2.1.4. Data Sources

2.1.5. Data Analysis

2.1.6. Ethics

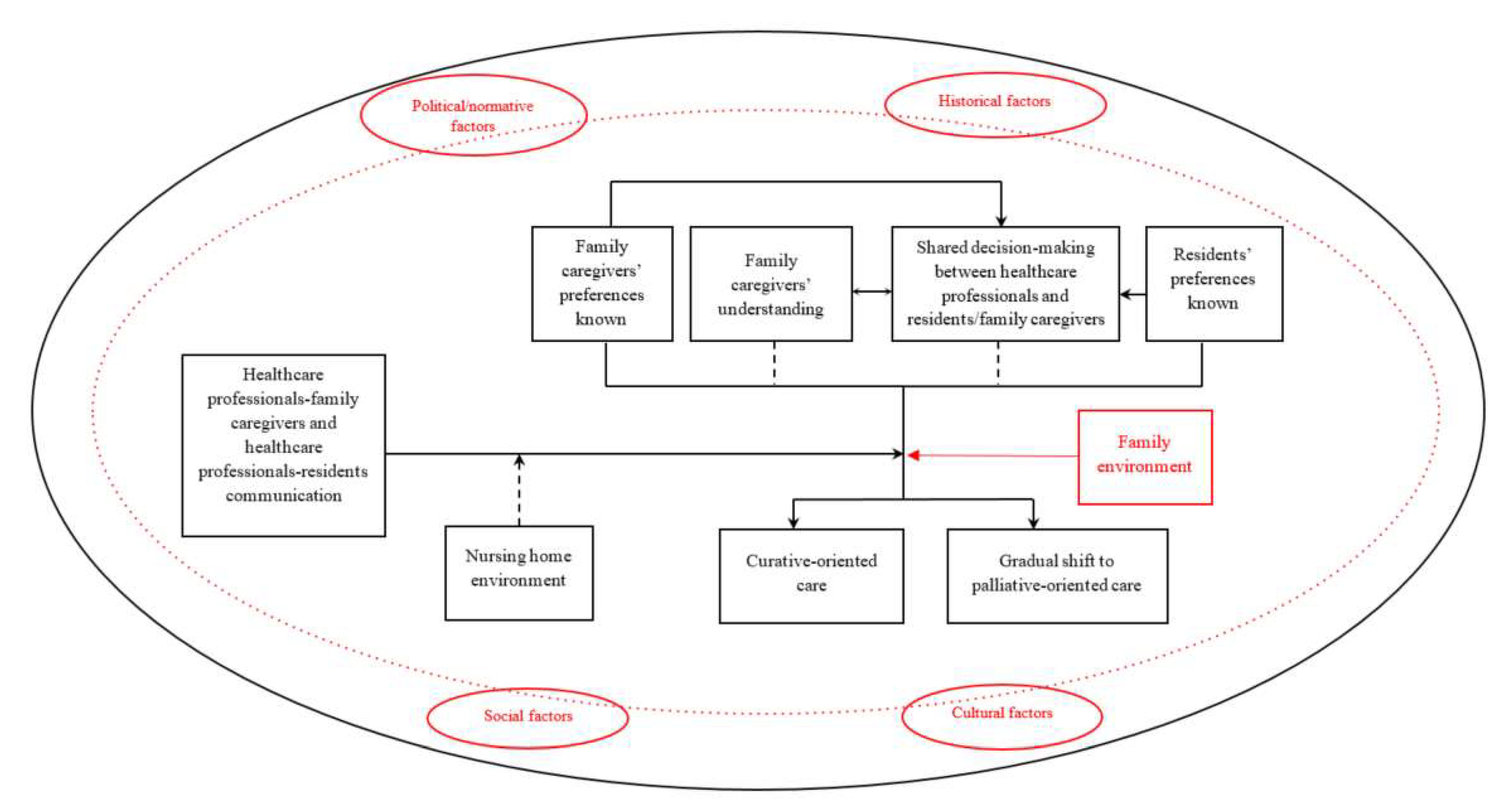

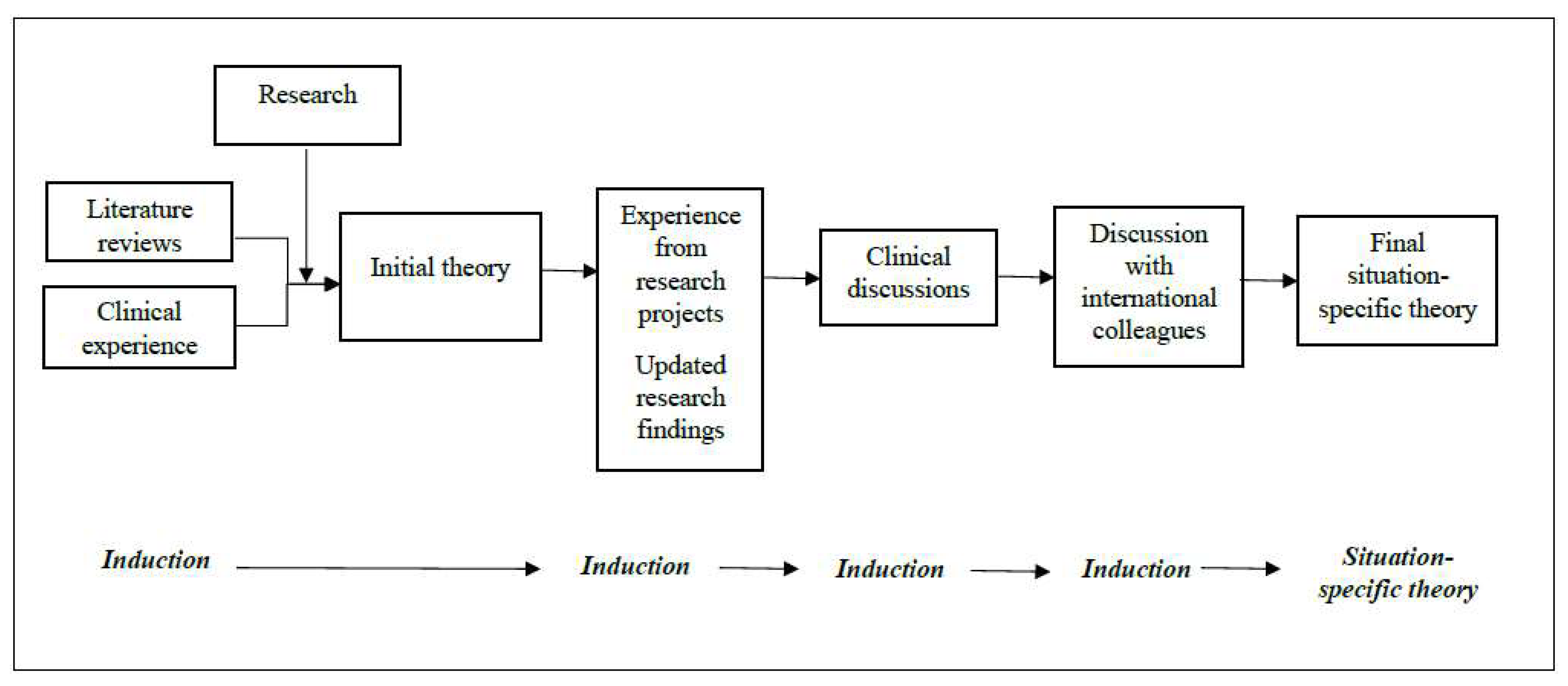

2.2. Development of a Situation-Specific Theory of End-of-Life Communication in Nursing Homes

2.2.1. Checking Assumptions

2.2.2. Multiple Sources of Theorizing

2.2.3. Theorizing: Initiation, Process, and Integration

2.2.4. Reporting, Sharing, and Validating Theorization

3. Results

3.1. Healthcare Professionals–Family Caregivers and Healthcare Professionals–Resident Communication

“They [NH staff] tell me what they want to tell, I don’t know if they tell me everything. I feel that sometimes communication is missed.”/“This clear communication reassured me, now I feel calmer and have clearer ideas.”(Pre- and post-FCC interview, FC1)

“Family meetings take place when we need to inform the family about care decisions we made or on their request.”/“In the weeks and months following the FCC, FCs needed more informal communication and updates. I took the time to continue such encounters.”(Pre- and post-FCC interview, staff member 1)

“Scheduled meetings with the medical/nursing staff would be useful for family who need feedback and should become routine.”(Post-FCC interview, FC4)

3.2. Family Caregivers’ Understanding

“My mum’s illness is progressing, in my opinion, no important decisions need to be made.”/“I did not know that hydration may be enough when she stops eating and we can avoid the need to insert a feeding tube.”(Pre- and post-FCC interview, FC1)

“The FCC made me reflect on things that one unconsciously knows, provided me with awareness of what could happen, and helped me to understand the pros and cons of the choices. One often tends to bury one’s head in the sand while saying ‘there is time’. Reading the booklet and then discussing it with M. made me open my eyes earlier.”(Post-FCC interview/FC6)

“Family meetings allow us to answer family doubts, provide further explanations if necessary, and promote awareness about the pathophysiology of the disease and possible complications.”/“The relative realized that aggressive treatments do not make sense.”(Pre- and post-FCC interview, staff member 3)

3.4. Residents’ Preferences Known

“When people with dementia transition into NHs, they are often no longer cognitively competent, we cannot explore their care preferences anymore, and they usually had not been asked earlier ‘What would you want if that happened to you?’. I see this as a very critical issue and we need to work on this to provide goal-concordant care when the person cannot express their preference anymore.”/“The project allowed us to give voice to the preferences of the residents by promoting reflection among their FCs. This guided the adjustment of the care plan and the provision of care that is potentially consistent with the residents’ preferences.”(Pre-FCC and post-FCC interview, staff member 1)

“My mum has always been a strong woman, and I think that this is no longer a way of life for her. She is vegetating on a bed [...] I wonder if my mum was still cognitively competent, stuck in a bed, what would she want to do? As we have known her, my sister and me, I don’t think she would like to go on.”(Post-FCC interview, FC3)

“I never asked my mum about this and she never brought it up. She has always been a combative spirit, full of energy, but she has dramatically deteriorated in a short time […]. I cannot perceive to what extent she will want to be attached to life.”(Post-FCC interview, FC6)

3.5. Family Caregivers’ Preferences Known

“The meeting clarified things for me and now both the facility and I know which decision I’ll make [...]. I want to limit my mum’s suffering as much as possible and ensure she dies peacefully. I made this clear with the staff and they agreed with me.”(Post-FCC interview, FC4)

“The project does not allow us to elicit residents’ preferences, but gives their FCs the opportunity to reflect both on their own care preferences and on their relative’s potential ones. This reflection then makes the FCs interact with the staff with a different awareness.”(Post-FCC interview, research staff)

“Some FCs tell you ‘I want to carry my mum to the hospital if she gets worse, I want to do everything possible [...]’. Instead, others called for a painless dignified death.”(Pre-FCC, staff member 3)

“FCCs provided space for shared reflection on topics that FCs often have never been faced with before and are reluctant to engage in.”(Post-FCC, staff member 2)

3.6. Contextual Factors

3.6.1. Family Environment

“My sister and I are in sync, perhaps because we know our mum well. We move forward and make decisions together as we have always done.”(Post-FCC interview, FC3)

“My daughter and I both read the information the NH provided us. She helps me a lot with these things, she is very sensitive. Then, we discussed it and participated together in the FCC. My brothers also read the booklet: at first, they told me that it was not the case, that there was time; then, when I told them what we had discussed in the FCC they said it sounded good.”(Post-FCC interview, FC6)

3.6.2. Nursing Home Environment

“This is a young facility, we are still running-in. This can be an advantage since practices have not yet been fully consolidated, there is some possibility to sow change.”(Pre-FCC interview, staff member 2)

“We try to establish collaborative and trusting relationships with family caregivers. We want a familiar atmosphere.”(Pre-FCC interview, staff member 3)

“I don’t worry, if something happens I know I can ask and they [NH staff] will answer. I trust them.”(Post-FCC interview, FC4)

“We want to improve the quality of care we provide. Thereby, we are interested in joining projects and getting trained on whatever topics can help us to reach this mission.”(Post-FCC interview, NH manager)

3.6.3. Political/Normative, Historical, Social, and Cultural Factors External to the Nursing Home Environment

Political/Normative Factors

“The NH staff are always in a rush.”(Post-FCC interview, FC1)

“I realize how my mum is doing depending on the number of tubes, oxygen, drip, or catheter. I ask for information only when I meet a nurse by chance [...]. My perception is that they are very understaffed.”(Post-FCC interview, FC3)

“There is consensus that FCCs improve the quality of care and family satisfaction with the care and the support received. FCCs need to become routine, we cannot deny persons something with proven efficacy. However, if we really want to improve NH care, the responsibility should not be left to the individual facility, the individual NH manager, or the individual nurse’s good will, but there should be broader supportive guidelines at the regional or national level that adjust current NH staffing. NHs should be given more staff: this would be a tangible signal that communication is recognized as time of care.”(Post-FCC interview, research staff)

Historical Factors

“The difficulties in recruiting personnel and the almost total turnover of the nursing personnel are clear indicators of the ongoing transformation that has been taking place over the last year [...]. The pandemic did not allow us to establish trusting relationships between staff and family.”(In-the-field notes)

“When we come to visit, we are now locked in the room, you do not see or talk to anyone [...]. At this moment, we are not much involved in care decisions.”(Post-FCC interview, FC3)

“The project has been useful to partially recover trusting relationships which had been lost during the pandemic. Visitation restrictions made FCs feel poorly informed and involved in care decisions. These family meetings represented the starting point to recovering relationships.”(Post-FCC interview, staff member 1)

Social Factors

“My sister and I have a profound sense of duty towards our mum. We have not abandoned her after she transitioned into this home, we want to be present. We act this way probably because we grew up with these values.”(Post-FCC interview, FC3)

Cultural Factors

“I want to avoid hospitalization and desire my mum to be accompanied, you understand for what.”(Pre-FCC interview, FC2)

“Within our family, we are not used to discussing such topics. Our mum has never explicitly spoken to us about these issues.”(Post-FCC interview, FC3)

“FCs are usually reluctant to engage in care conversations because they do not want to think about serious decisions they will be asked to take for their relative.”(Post-FCC interview, NH manager)

“This study allows us to reflect and discuss topics that are usually pushed away and denied.”(In-the-field notes)

“The end of life is often a taboo within the family. Children do not discuss these issues with their parents while they are still cognitively competent. Thus, at the end of life, they are faced with making decisions based on what they think the parent would have wanted. Anyway, it’s always a guessing game, which comes with a significant emotional and decision-making burden.”(Post-FCC interview, research staff)

3.7. Residents- and Family Caregivers-Related Care Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Elements of the Existing End-of-Life Communication Theory | Contextual Factors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Healthcare Professionals–Family Caregivers and Healthcare Professionals–Residents Communication | Family Caregivers’ Understanding | Shared Decision-Making Between Healthcare Professionals and Residents/Family Caregivers | Residents’ Preferences Known | Family Caregivers’ Preferences Known | Family Environment | Nursing Home Environment | Contextual Factors (i.e., Political/Normative, Historical, Social, and Cultural Factors) |

| Pre-FCC interview, FC1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Pre-FCC interview, FC2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ |

| Pre-FCC interview, staff member1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, staff member1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Pre-FCC interview, staff member2 | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ | ✕ |

| Post-FCC interview, staff member2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Pre-FCC interview, staff member3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, staff member3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Pre-FCC interview, nursing home manager | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, nursing home manager | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, research staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC4 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC5 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC6 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC7 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC8 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC9 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC10 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Post-FCC interview, FC11 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ |

Appendix B

| Resident, FAST Score | Family Caregiver | Pre Family Care Conference c | Family Care Conference | Post-Family Care Conference d | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Caregiver | Resident | Participants | Topics Discussed | Family Caregiver | Resident | ||||||||

| Perceived Decisional Conflicts a Mean (SD) | Perceived Care Quality b Mean (SD) | Community-Based Services used | Hospital Services used | Documents Completed | Perceived Decisional Conflicts a Mean (SD) | Perceived care Quality b Mean (SD) | Community-Based Services Used | Hospital Services Used | Documents Completed | ||||

| 1, 7a | Daughter, 75 years, higher education | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.8 (1.6) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist, wound care specialist nurse | Wound care outpatient department | - | Daughter, nurse | When hospitalization may be useful Symptom control at the end of life CPR Who can take decisions | 1.3 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.5) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | ADRT |

| 2, 7a | Daughter, 67 years, higher education | 1 (0) | 6.6 (1.0) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | - | - | Daughter, nurse, psychologist | When hospitalization may be useful Disease trajectory and possible complications Who can take decisions | 1.0 (0) | 4.8 (1.4) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | None |

| 3, 7d | Son, 49 years, higher education | 1.4 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.5) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | Emergency department, cardiology outpatient department | - | Daughter, son, nurse | When hospitalization may be useful How much time is left and quality of life Role of family caregivers in care decisions Communication with staff | 2.9 (0.6) | 5.0 (0.9) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | ADRT |

| 4, 7c | Daughter, 57 years, higher education | 1.2 (0.5) | 5.7 (0.7) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | - | - | Daughter, nurse | Role of family caregivers in care decisions Changes in the last days/hours of life Communication with staff | 1.4 (0.37) | 5.6 (1.1) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | None |

| 5, 7a | Niece, 51 years, higher education | 0.1 (0.3) | 6.8 (0.4) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist, neurologist | Emergency department, hospital admission | - | Three grandchildren | When hospitalization may be useful Symptom control at the end of life Role of family caregivers in care decisions Choice of legal guardian | 0 (0) | 6.7 (0.7) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | ADRT, signature of the power of attorney |

| 6, 7a | Daughter, 55 years, higher education | 2.1 (0.9) | 4.6 (1.4) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist, neurologist | Center of Cognitive Disorders and Dementias | - | Daughter, granddaughter, nurse | Role of family caregivers in care decisions Choice of legal guardian Implications of having a pacemaker at the end of life | 1.3 (0.8) | 5.3 (1.2) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | ADRT |

| 7, 7a | Son, 52 years, higher education | 1.3 (0.7) | 5.8 (0.8) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | Urology outpatient department | - | Son, nurse | When hospitalization may be useful Role of family caregivers in care decisions How to document decisions in clinical records | 0.2 (0.8) | 6.6 (0.9) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist, nurse stomatherapist | Urology outpatient department | ADRT, signature of the power of attorney |

| 8, 7a | Son, 60 years, higher education | 2.5 (0.9) | 5.2 (1.5) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | Gynecological outpatient department | - | Son, nurse | Symptom control at the end of life How to document decisions in clinical records | 0.6 (1.1) | 5.8 (1.3) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | ADRT |

| 9, 7b | Daughter, 58 years, higher education | 3.8 (0.8) | 4.9 (0.7) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | - | - | Daughter, nurse, psychologist | Role of family caregivers in care decisions Expected changes at the end of life | 1.3 (0.6) | 5.6 (0.7) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | None |

| 10, 7d | Niece, 52 years, higher education | 1.0 (0.4) | 7.0 (0) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | - | - | Niece, nurse | When hospitalization may be useful Symptom control at the end of life | 0 (0) | 7.0 (0) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | ADRT |

| 11, 7d | Son, 60 years, higher education | 2.7 (0.7) | 5.7 (0.7) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | Emergency department, hospital admission | - | Son, nurse | Expected changes at the end of life Symptom control at the end of life When hospitalization may be useful Opportunity to stay close to the relative at the end of life | 1.2 (0.5) | 6.0 (0.5) | GP, psychologist, physiotherapist | None | ADRT |

References

- Broad, J.B.; Gott, M.; Kim, H.; Boyd, M.; Chen, H.; Connolly, M.J. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Etkind, S.N.; Verne, J.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? Population-based projections of place of death. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joling, K.J.; Janssen, O.; Francke, A.L.; Verheij, R.A.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; Visser, P.J.; van Hout, H.P.J. Time from diagnosis to institutionalization and death in people with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honinx, E.; van Dop, N.; Smets, T.; Deliens, L.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Froggatt, K.; Gambassi, G.; Kylänen, M.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; Szczerbińska, K.; et al. Dying in long-term care facilities in Europe: The PACE epidemiological study of deceased residents in six countries. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Hack, T.; Rodger, K.; St John, P.; Chochinov, H.; McClement, S. Clarifying the information and support needs of family caregivers of nursing home residents with advancing dementia. Dementia 2021, 20, 1250–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vick, J.B.; Ornstein, K.A.; Szanton, S.L.; Dy, S.M.; Wolff, J.L. Does caregiving strain increase as patients with and without dementia approach the end of life? J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 199–208.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Mitchell, G.; Bavelaar, L.; Conti, A.; Vanalli, M.; Basso, I.; Cornally, N. Interventions to support family caregivers of people with advanced dementia at the end of life in nursing homes: A mixed-methods systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2021, 36, 268–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschieri, F.; Barello, S.; Durosini, I. “Invisible Voices”: A critical incident study of family caregivers’ experience of nursing homes after their elder relative’s death. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Basso, I.; Clari, M.; Di Giulio, P. A qualitative study of family carers views on how end-of-life communication contributes to palliative-oriented care in nursing home. Ann. Ist. Super Sanita 2020, 56, 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, L.H.; Bynum, J.P.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Weir, D.R.; Langa, K.M. Advance directives and nursing home stays associated with less aggressive end-of-life care for patients with severe dementia. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Basso, I.; Dimonte, V.; Martin, B.; Berchialla, P.; Campagna, S.; Di Giulio, P. Association between end-of-life conversations in nursing homes and end-of-life care outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetle, T.; Shield, R.; Teno, J.; Miller, S.C.; Welch, L. Family perspectives on end-of-life care experiences in nursing homes. Gerontologist 2005, 45, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honinx, E.; Block, L.V.D.; Piers, R.; Van Kuijk, S.M.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Payne, S.A.; Szczerbińska, K.; Gambassi, G.G.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Deliens, L.; et al. Potentially inappropriate treatments at the end of life in nursing home residents: Findings from the PACE cross-sectional study in six European countries. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 732–742.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honinx, E.; Piers, R.D.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Payne, S.; Szczerbińska, K.; Gambassi, G.; Kylänen, M.; Deliens, L.; Van den Block, L.; Smets, T. Hospitalisation in the last month of life and in-hospital death of nursing home residents: A cross-sectional analysis of six European countries. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toles, M.; Song, M.K.; Lin, F.C.; Hanson, L.C. Perceptions of family decision-makers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia regarding the quality of communication around end-of-life care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.L.; Teno, J.M.; Kiely, D.K.; Shaffer, M.L.; Jones, R.N.; Prigerson, H.G.; Volicer, L.; Givens, J.L.; Hamel, M.B. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, J.P.; Downes, D.; Cimarolli, V.; Bomba, P. End-of-life conversations and hospice placement: Association with less aggressive care desired in the nursing home. J. Soc. Work. End-of-Life Palliat. Care 2017, 13, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, L.; Johnell, K.; Van den Block, L.; Aubry, R. Discussing end-of-life issues in nursing homes: A nationwide study in France. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernacki, R.E.; Block, S.D. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsky, J.A.; Beach, M.C.; Butow, P.N.; Hickman, S.E.; Mack, J.W.; Morrison, R.S.; Street, R.L., Jr.; Sudore, R.L.; White, D.B.; Pollak, K.I. A Research agenda for communication between health care professionals and patients living with serious illness. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Basso, I.; Dimonte, V.; Giulio, P.D. The role of end-of-life communication in contributing to palliative-oriented care at the end-of-life in nursing home. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2022, 28, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jairath, N.N.; Peden-McAlpine, C.J.; Sullivan, M.C.; Vessey, J.A.; Henly, S.J. Theory and theorizing in nursing science: Commentary from the nursing research special issue editorial team. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, C. Key issues in nursing theory: Developments, challenges, and future directions. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, E.O.; Meleis, A.I. Situation-specific theories: Philosophical roots, properties, and approach. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1999, 22, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M.; Brown, W.J. Culture, self, and collectivist communication: Linking culture to individual behavior. Hum. Commun. Res. 1995, 21, 354–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, E.O. Development of situation-specific theories: An integrative approach. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2005, 28, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, A.J.E.; Doherty, J.; Bavelaar, L.; Walshe, C.; Preston, N.; Kaasalainen, S.; Sussman, T.; van der Steen, J.T.; Cornally, N.; Hartigan, I.; et al. A family carer decision support intervention for people with advanced dementia residing in a nursing home: A study protocol for an international advance care planning intervention (mySupport study). BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, P.; Quinn, K.; O’Hanlon, B.; Aranda, S. Family meetings in palliative care: Multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines. BMC Palliat. Care 2008, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, E.; Perobelli, E.; Rotolo, A.; Berloto, S. Lessons learned from Italian nursing homes during the COVID-19 outbreak: A tale of long-term care fragility and policy failure. J. Long-Term Care 2021, 2021, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, I.; Bonaudo, M.; Dimonte, V.; Campagna, S. Le missed care negli ospiti delle residenze sanitarie per anziani: Risultati di uno studio pilota [The missed care in nursing homes: A pilot study]. Assist. Inferm. Ric. 2018, 37, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davies, N.; De Souza, T.; Rait, G.; Meehan, J.; Sampson, E.L. Developing an applied model for making decisions towards the end of life about care for someone with dementia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.M. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med. Decis. Mak. 1995, 15, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohra, J.U.; Brazil, K.; Hanna, S.; Abelson, J. Family perceptions of end-of-life care in long-term care facilities. J. Palliat. Care 2004, 20, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Basso, I.; De Marinis, M.G.; Campagna, S.; Di Giulio, P. Good end-of-life care in nursing home according to the family carers’ perspective: A systematic review of qualitative findings. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Campagna, S.; Basso, I.; De Marinis, M.G.; Di Giulio, P. Mechanisms by which end-of-life communication influences palliative-oriented care in nursing homes: A scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 2134–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Clari, M.; Basso, I.; Di Giulio, P. What contributes to family carers’ decision to transition towards palliative-oriented care for their relatives in nursing homes? Qualitative findings from bereaved family carers’ experiences. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 19, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Basso, I.; Clari, M.; Dimonte, V.; Di Giulio, P. A qualitative study of nurses’ perspective about the impact of end-of-life communication on the goal of end-of-life care in nursing home. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonella, S.; Gonella, S.; Di Giulio, P.; Angaramo, M.; Dimonte, V.; Campagna, S.; Brazil, K.; mySupport study group. Implementing a nurse-led quality improvement project in nursing home during COVID 19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Int. Health Trends Perspect. 2022, 2, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendrich-van Dael, A.; Bunn, F.; Lynch, J.; Pivodic, L.; Van den Block, L.; Goodman, C. Advance care planning for people living with dementia: An umbrella review of effectiveness and experiences. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 107, 103576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavelaar, L.; Van Der Steen, H.; De Jong, H.; Carter, G.; Brazil, K.; Achterberg, W.; van der Steen, J. Physicians’ perceived barriers and proposed solutions for high-quality palliative care in dementia in the Netherlands: Qualitative analysis of survey data. J. Nurs. Home Res. Sci. 2021, 7, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.L.; Palmer, J.A.; Volandes, A.E.; Hanson, L.C.; Habtemariam, D.; Shaffer, M.L. Level of care preferences among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Steen, J.T.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Knol, D.L.; Ribbe, M.W.; Deliens, L. Caregivers’ understanding of dementia predicts patients’ comfort at death: A prospective observational study. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maust, D.T.; Blass, D.M.; Black, B.S.; Rabins, P.V. Treatment decisions regarding hospitalization and surgery for nursing home residents with advanced dementia: The CareAD Study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2008, 20, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscani, F.; van der Steen, J.T.; Finetti, S.; Giunco, F.; Pettenati, F.; Villani, D.; Monti, M.; Gentile, S.; Charrier, L.; Di Giulio, P. Critical decisions for older people with advanced dementia: A prospective study in long-term institutions and district home care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 535.e13–535.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Gjengedal, E.; Rosland, J.H. They know!-Do they? A qualitative study of residents and relatives views on advance care planning, end-of-life care, and decision-making in nursing homes. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemmt, M.; Henking, T.; Heizmann, E.; Best, L.; van Oorschot, B.; Neuderth, S. Wishes and needs of nursing home residents and their relatives regarding end-of-life decision-making and care planning-A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzeng, E.; Colaianni, A.; Roland, M.; Chander, G.; Smith, T.J.; Kelly, M.P.; Barclay, S.; Levine, D. Influence of institutional culture and policies on do-not-resuscitate decision making at the end of life. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes-Thompson, S.; Gessert, C.E. End of life in nursing homes: Connections between structure, process, and outcomes. J. Palliat. Med. 2005, 8, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranley, L.A.; Hoben, M.; Yeung, J.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Norton, P.G.; Wagg, A. SCOPEOUT: Sustainability and spread of quality improvement activities in long-term care- a mixed methods approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visetti, G. RSA, Infermieri in Fuga: “é Come Stare in Guerra ma Senza più Soldati” [Nursing Homes, Nurses on the Run: It’s Like Being in War But without Soldiers]. 2020. Available online: https://www.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/11/03/news/rsa_infermieri_in_fuga_e_come_stare_in_guerra_ma_senza_piu_soldati_-301044443/ (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Gonella, S.; Di Giulio, P.; Antal, A.; Cornally, N.; Martin, P.; Campagna, S.; Dimonte, V. Challenges experienced by Italian nursing home staff in end-of-life conversations with family caregivers during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertini, M.; Mantovani, D. Older parents and filial support obligations: A comparison of family solidarity norms between native and immigrant populations in Italy. Ageing Soc. 2021, 42, 2556–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscani, F.; Farsides, C. Deception, catholicism, and hope: Understanding problems in the communication of unfavorable prognoses in traditionally-catholic countries. Am. J. Bioeth. 2006, 6, W6–W18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time Point | Family Caregivers | Nursing Home Staff | Nursing Home Manager | Research Staff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-family care conference |

|

|

| |

| Post-family care conference |

|

|

|

|

| Data Collection Methods | Time Point | |

|---|---|---|

| Before Family Care Conference | After Family Care Conference | |

| Residents’ clinical records (N) | 11 | 11 |

| Family caregivers’ self-administered questionnaire (N) | 11 | 11 |

| Family caregivers’ semi-structured interviews (N) | 2 | 11 |

| Nursing home staff semi-structured interviews (N) | 3 | 3 |

| Nursing home manager semi-structured interview (N) | 1 | 1 |

| Research staff semi-structured interview (N) | - | 1 |

| In-the-field notes | Collected | Collected |

| Inductive Approach | Deductive Approach | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Units of Meaning | Codes | Sub-Categories | Categories |

| A FC said: “My mum cannot decide anything, others always decide for her. Sometimes I think ‘Will they make the right or wrong decisions?’.” | Doubting that HCPs make the best care choices | Level of trust | Shared decision-making between healthcare professionals and residents/family caregivers |

| A FC said: “I’m calmer now because they know what I think and I know what they think. We have agreed on the path to follow.” | Trusting the HCPs | ||

| A research staff member said: “Following the FCC, FCs feel much more involved in decisions.” | Feeling involved in decisions | Family involvement in end-of-life care decisions | |

| A HCP said: “FCCs allowed FCs to be engaged in end-of-life decisions, provided space for sharing and communication, thus enriching the end-of-life experience of FCs.” | Providing FCs space for discussion | ||

| A research staff member said: “Following the FCC, FCs feel […] more emotionally-supported.” | Feeling emotionally supported | Establishing a partnership between HCPs and FCs | |

| A HCP said: “It has been a wonderful piece of work […]. FCs felt recognized as caregivers and familiar relationships based on mutual respect and with stronger bonds than before were established.” | Strengthening relationships with FCs | ||

| Before Family Care Conference N = 6 n/N | After Family Care Conference N = 16 n/N | |

|---|---|---|

| Elements of the existing end-of-life communication theory | ||

| Healthcare professionals–family caregivers and healthcare professionals–residents communication | 6/6 | 16/16 |

| Family caregivers’ understanding | 4/6 | 16/16 |

| Shared decision-making between healthcare professionals and residents/family caregivers | 6/6 | 16/16 |

| Residents’ preferences known | 4/6 | 8/16 |

| Family caregivers’ preferences known | 2/6 | 16/16 |

| Contextual factors | ||

| Family environment | 3/6 | 13/16 |

| Nursing home environment | 3/6 | 14/16 |

| Contextual factors (i.e., political/normative, historical, social, and cultural factors) | 5/6 | 14/16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonella, S.; Campagna, S.; Dimonte, V. A Situation-Specific Theory of End-of-Life Communication in Nursing Homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010869

Gonella S, Campagna S, Dimonte V. A Situation-Specific Theory of End-of-Life Communication in Nursing Homes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010869

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonella, Silvia, Sara Campagna, and Valerio Dimonte. 2023. "A Situation-Specific Theory of End-of-Life Communication in Nursing Homes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010869

APA StyleGonella, S., Campagna, S., & Dimonte, V. (2023). A Situation-Specific Theory of End-of-Life Communication in Nursing Homes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010869