Perceived Barriers of Accessing Healthcare among Migrant Workers in Thailand during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Financial Barriers

- Lack of migrant health insurance

“In the past, the government had a plan to take care of undocumented migrants who did not have any passports or any personal identity evidence…Yet, de facto, those migrants were not able to visit any health facilities… As such, this leads to refusal from health facilities to provide health screening for undocumented migrants especially in the COVID-19 pandemic”.(C01)

- Unaffordability of hospital care

“With limited income, migrant workers or undocumented migrants could not afford to pay for medical bills. The bill is high”.(F10)

- Unstable employment status

“COVID-19 interrupted our VISA extension, and then some migrant workers cannot continue their VISA validity. This resulted in negative impacts on access to health insurance. Moreover, some migrant workers needed to shift their work and then change their employers. This circumstance can limit our access to social security scheme and health insurance too. Also, the type of work can affect health screening, and it is even worse when they found that they were infected. Migrant workers in small companies needed to drop out of their work once they got infected, and it meaned that they lived without payment”.(C01)

“Once they have no jobs, it means that they lose their income”.(D01)

“The government is the key decisionmaker. Closure on the construction sites was implemented without any relief plans. We are unsure what we should do next”.(B01)

3.2. Structural Barriers

- Constraint in health system design

“Home isolation for migrant workers is challenging. At the construction sites, their living conditions did not enable them to do self-quarantine. Some of them are living in small shelters and work transfer is quite common for them. In normal situation, poor living conditions are obvious, and it is even worse during this pandemic”.(F10)

- Service adjustment during the COVID-19 period

“Over the first wave of the crisis, health facilities denied migrants with positive cases. Thai patients were priority. They urged us (migrants) to stay home”.(D01)

3.3. Cognitive Barriers

- Negative attitudes towards migrant workers

“There were growing trends of negative attitudes towards migrant workers, particularly when new migrant COVID-19 cases were found in communities. Burmese migrant workers were prohibited from entering (some) fresh markets. There was a sign stopping them at the entrance. They were afraid that these people would bring more infection in the area. Surely, those migrants would face more difficulties in their daily life”.(F10)

- Language and communication barriers

”Yesterday we were informed that workplaces planned to contain the spread of COVID-19 by sealing the workplaces. This measure needed to be explained explicitly to migrant workers, and we needed to educate them…But the staff did not know how to explain them as we spoke in different languages…Some migrant workers could not access knowledge sources and had poor health literacy to take care of themselves during the spread of COVID-19. There was misunderstanding (in the sense of improper use) about self-protection; how to wear masks, hand gels, or soaps”.(C02)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Doung-Ngern, P.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Panjangampatthana, A.; Janekrongtham, C.; Ruampoom, D.; Daochaeng, N.; Eungkanit, N.; Pisitpayat, N.; Srisong, N.; Yasopa, O.; et al. Case-Control Study of Use of Personal Protective Measures and Risk for SARS-CoV2 Infection, Thailand. Emerg. Infect Dis. 2020, 26, 2607–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajatanavin, N.; Tuangratananon, T.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Responding to the COVID-19 second wave in Thailand by diversifying and adapting lessons from the first wave. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marome, W.; Shaw, R. COVID-19 Response in Thailand and Its Implications on Future Preparedness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uansri, S.; Tuangratananon, T.; Phaiyarom, M.; Rajatanavin, N.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Jaruwanno, W. Predicted Impact of the Lockdown Measure in Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Greater Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand. Thailand Migration Report 2019; United Nations: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; Available online: https://thailand.iom.int/sites/thailand/files/document/publications/Thailand%20Report%202019_22012019_HiRes.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- World Health Organization. Interim Guidance for Refugee and Migrant Health in Relation to COVID-19 in the WHO European Region. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/434978/Interim-guidance-refugee-and-migrant-health-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Kang, S.J.; Hyung, J.A.; Han, H.R. Health literacy and health care experiences of migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, D. Migrant workers and COVID-19. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 634–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Pudpong, N.; Prakongsai, P.; Putthasri, W.; Hanefeld, J.; Mills, A. The Devil Is in the Detail-Understanding Divergence between Intention and Implementation of Health Policy for Undocumented Migrants in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunpeuk, W.; Teekasap, P.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Julchoo, S.; Phaiyarom, M.; Sinam, P.; Pudpong, N.; Suphanchaimat, R. Understanding the Problem of Access to Public Health Insurance Schemes among Cross-Border Migrants in Thailand through Systems Thinking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, J.E.; Carrillo, V.A.; Perez, H.R.; Salas-Lopez, D.; Natale-Pereira, A.; Byron, A.T. Defining and targeting health care access barriers. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2011, 22, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, J.; Gilbert, P. A Handbook of Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- Arayawong, W.S.C.; Thanaisawanyangkoon, S.; Punjangampattana, A. Training Curriculum of Migrant Health Volunteers; Suteerawut, T., Haruthai, C., Thanaisawanyangkoon, S., Punjangampattana, A., Eds.; Thepp.envanich Printing: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2016; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. What Has Been the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immigrants? An Update on Recent Evidenceq. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/what-is-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-immigrants-and-their-children-e7cbb7de/ (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Abba-Aji, M.; Stuckler, D.; Galea, S.; McKee, M. Ethnic/racial minorities’ and migrants’ access to COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. J. Migr. Health 2022, 5, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Evolution and complexity of government policies to protect the health of undocumented/illegal migrants in Thailand—The unsolved challenges. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2017, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunpeuk, W.; Julchoo, S.; Phaiyarom, M.; Sinam, P.; Pudpong, N.; Loganathan, T.; Yi, H.; Suphanchaimat, R. Access to Healthcare and Social Protection among Migrant Workers in Thailand before and during COVID-19 Era: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations in Thailand. Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of COVID-19 in Thailand. Bangkok. 2020. Available online: https://www.th.undp.org/content/thailand/en/home/library/socio-economic-impact-assessment-of-covid-19-in-thailand.html (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- International Organization for Migration. Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 on Migrant Workers in Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Thailand. IOM, Thailand. 2021. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/socioeconomic-impact-covid-19-migrant-workers-cambodia-lao-peoples-democratic-republic (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand. Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Underscored a Role of Migrants as Essential Partners for Sustainable Development at the Opening Session of the Asia-Pacific Regional Review of Implementation of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM). 2021. Available online: https://www.mfa.go.th/en/content/escapeng?cate=5d5bcb4e15e39c306000683e (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Papwijitsil, R.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Sinam, P.; Phaiyarom, M.; Julchoo, S.; Suphanchaimat, R. Factors Related to Health Risk Communication Outcomes among Migrant Workers in Thailand during COVID-19: A Case Study of Three Provinces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization of Migration, Thailand. IOM Thailand COVID-19 Response and Recovery Plan. 2021. Available online: https://thailand.iom.int/iom-thailand-covid-19-response (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- International Labour Organization. COVID-19: Impact on Migrant Workers and Country Response in Thailand. Bangkok. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/asia/publications/issue-briefs/WCMS_741920/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Ministry of Labour of Thailand. E-magazine MOL. 2021. Available online: https://www.mol.go.th/e_magazine (accessed on 16 May 2022).

| Code | Involvement with Social and Health Issues among Migrant Workers |

|---|---|

| Policymaker (Ministry of Public Health) | |

| A01 | Consultant of Deputy Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Public Health |

| A02 | Head of Health Administration Division, Ministry of Public Health |

| A03 | Consultant of Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health |

| A04 | Policymaker from the Division of Health Economics and Health Security, NHSO |

| A05 | Policymaker from the National Institute of Emergency Medicine |

| Policymaker (Other Ministry Participants) | |

| A06 | Advisor to the Minister of Social Development and Human Security, Thailand |

| A07 | Deputy Permanent Secretary of National Health Commission Office, Thailand |

| A08 | Head of National Health Security Office |

| A09 | Head of health promotion plan for vulnerable populations, ThaiHealth Promotion Foundation, Thailand |

| A10 | Staff of health promotion plan for vulnerable populations, ThaiHealth Promotion Foundation, Thailand |

| Healthcare professionals | |

| B01 | Medical doctor from Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health |

| B02 | Medical doctor from Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health |

| B03 | Public health academic who provides healthcare for detainees (Immigration Bureau) |

| B04 | Nurse who provides healthcare to detainee |

| B05 | Volunteer medical doctor who provides healthcare for COVID-19 patients in home isolation |

| Experts on migrant health (non-government organisations: NGOs) | |

| C01 | Staff who have experience in work related to health services and quality of life of migrants and/or foreigners |

| C02 | Staff who have experience in work related to health services and quality of life of migrants and/or foreigners |

| Migration workers | |

| D01 | Migrant health volunteer |

| D02 | Migrant health volunteer |

| D03 | Migrant health volunteer |

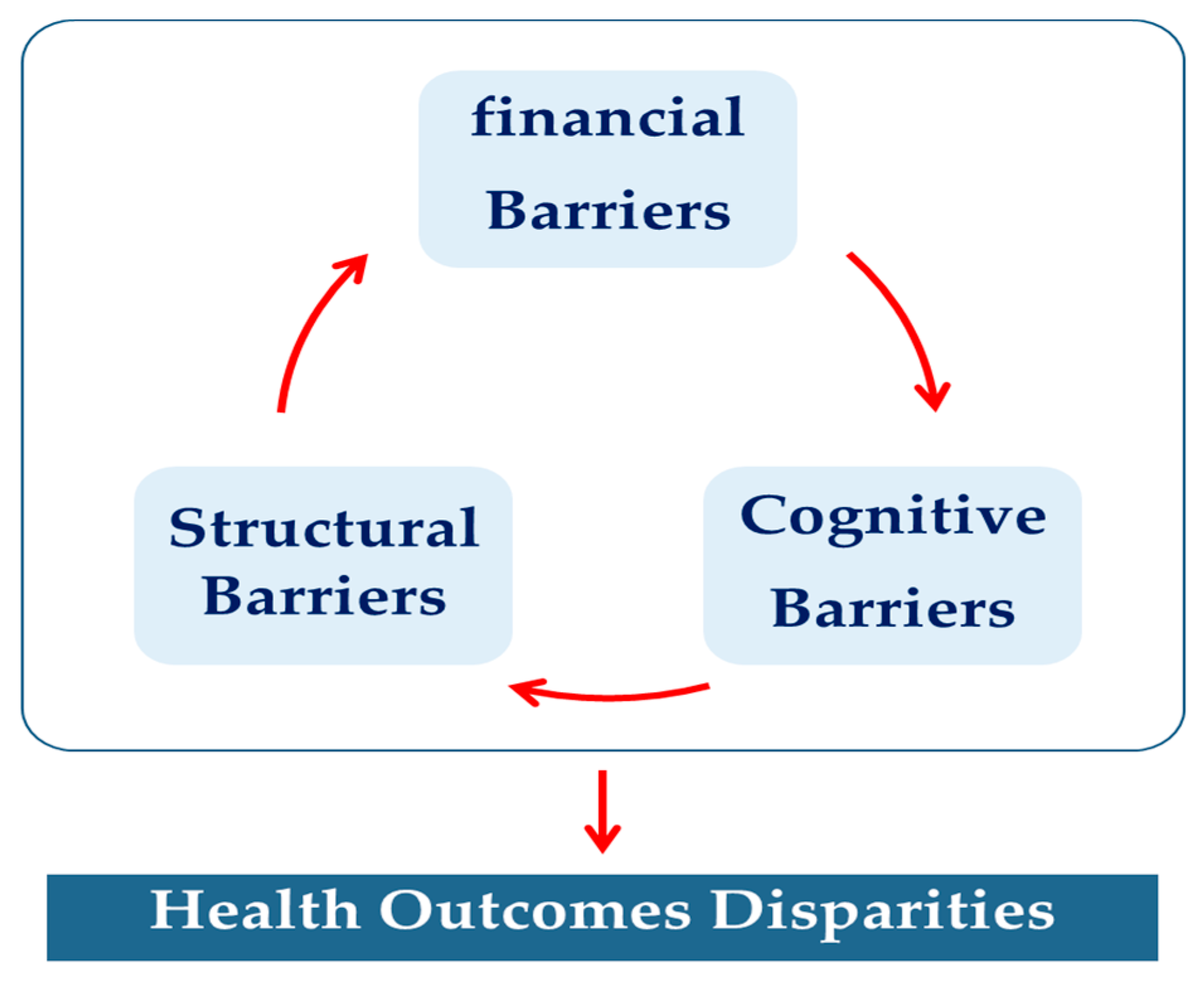

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Financial Barriers | 1. Lack of migrant health insurance |

| 2. Unaffordability of hospital care | |

| 3. Unstable employment status | |

| Structural Barriers | 1. Constraint in health system design |

| 2. Service adjustment during COVID-19 period | |

| Cognitive Barriers | 1. Negative attitudes towards migrant workers |

| 2. Language and communication barriers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uansri, S.; Kunpeuk, W.; Julchoo, S.; Sinam, P.; Phaiyarom, M.; Suphanchaimat, R. Perceived Barriers of Accessing Healthcare among Migrant Workers in Thailand during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105781

Uansri S, Kunpeuk W, Julchoo S, Sinam P, Phaiyarom M, Suphanchaimat R. Perceived Barriers of Accessing Healthcare among Migrant Workers in Thailand during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105781

Chicago/Turabian StyleUansri, Sonvanee, Watinee Kunpeuk, Sataporn Julchoo, Pigunkaew Sinam, Mathudara Phaiyarom, and Rapeepong Suphanchaimat. 2023. "Perceived Barriers of Accessing Healthcare among Migrant Workers in Thailand during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105781