Teamwork Management and Benefit of Telemedicine in COVID-19 Outbreak Control on an Offshore Vessel in the Gulf of Thailand, Songkhla Province, Thailand: A Case Report

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. COVID-19 Spreading Control on Board

2.2.1. Case Identification at the Arrival

2.2.2. Isolation for CoIC and Quarantine for CoCC Measures on Board

2.2.3. Telemedicine Usage for Health Monitoring

2.2.4. Plan for Evacuation

2.2.5. The Joint Working Group

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4. Ethics Considerations

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. COVID-19 Symptoms and the Results of the RT-PCR Tests for COVID-19 upon Arrival

3.3. Isolation and Quarantine Process

3.4. Repeated RT-PCR Tests Performed

3.5. SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern

3.6. Monitoring Health Status

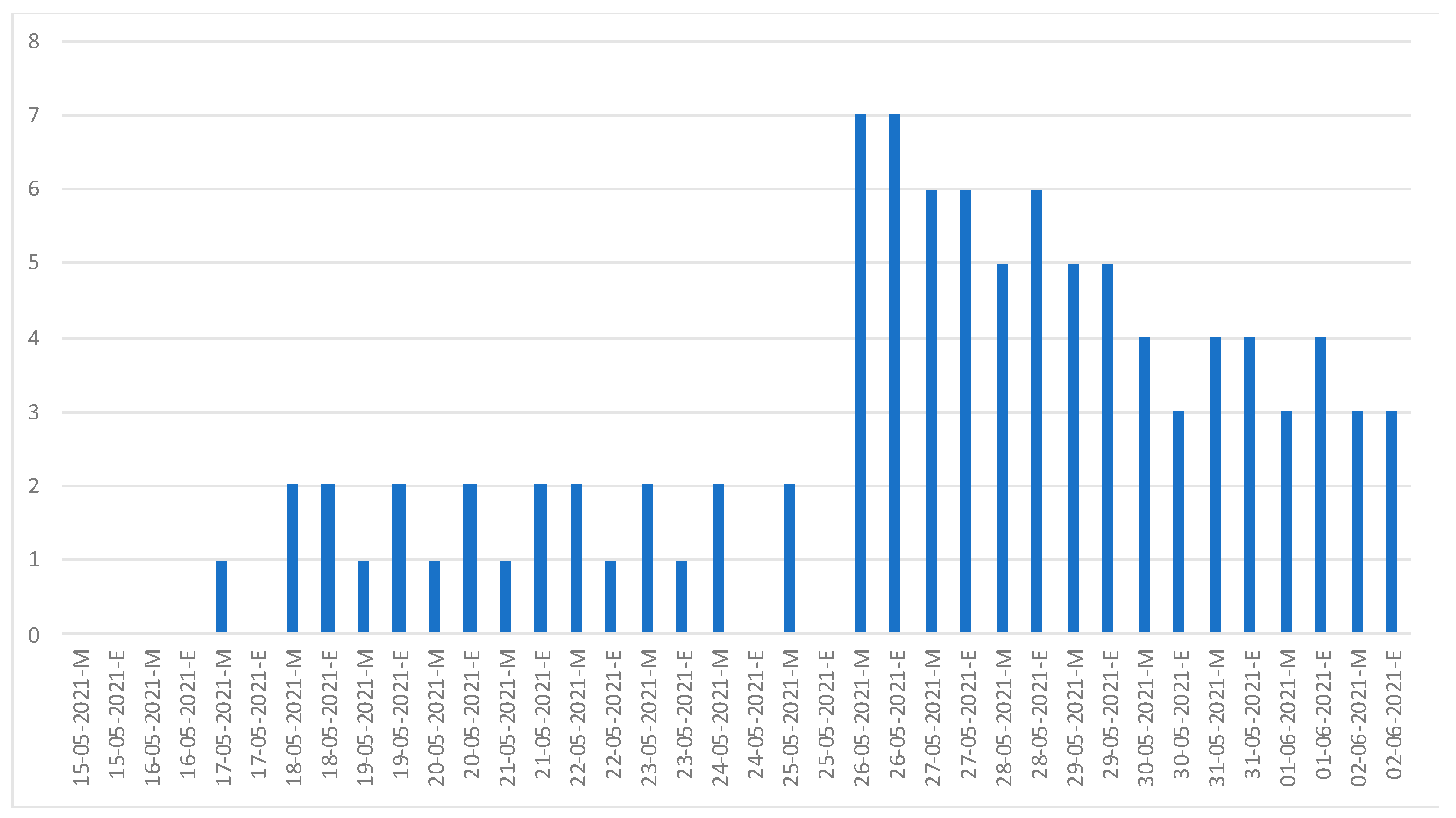

3.7. The Summary of the Journey

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Results

4.2. The Management of the Onboard Outbreak

4.3. The Benefit of Telemedicine

4.4. The Limitations and Learning Experiences of Medical Follow-Up via Telemedicine

4.5. Limitations of this Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Marinkovic, A.; Haider, N.; Abbasi, A.F.; Jaferi, U.; Prakash, S.; Balendra, V. The Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, 204993612110243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Interim Recommendations for Use of the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine, BNT162b2, under Emergency Use Listing. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-BNT162b2-2021.1 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Clinical Management: Living Guidance, 25 January 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/338882/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021.1-eng.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Yamagishi, T.; Doi, Y. Insights on Coronavirus Disease 2019 Epidemiology From a Historic Cruise Ship Quarantine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, e458–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19. 13 July 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---13-july-2021 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Department of Disease Control, the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://ddc.moph.go.th/viralpneumonia/eng/file/main/order_of_the_centre.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- World Health Organization. Guidance for Maritime Vessels on the Mitigation and Management of COVID-19|Quarantine|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/maritime/covid-19-ship-guidance.html (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. Operational Considerations for Managing COVID-19 Cases/Outbreak on Board Ships. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/operational-considerations-for-managing-covid-19-cases-or-outbreaks-on-board-ships-interim-guidance (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- International Chamber of Shipping. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Guidance for Ship Operators for the Protection of the Health of Seafarers, Third Edition. Available online: https://www.ics-shipping.org/publication/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-for-ship-operators-for-the-protection-of-the-health-of-seafarers-v3/ (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/Coronavirus.aspx (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- World Health Organization. Contact Tracing and Quarantine in the Context of COVID-19: Interim Guidance, 6 July 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-Contact_tracing_and_quarantine-2022.1 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- The Healthcare-Associated Infection Treatment and Prevention Working Group, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health. Guidelines on Clinical Practice, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infection for COVID-19. Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://ddc.moph.go.th/viralpneumonia/eng/file/guidelines/g_CPG_06may21.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Guha Niyogi, S.; Agarwal, R.; Suri, V.; Malhotra, P.; Jain, D.; Puri, G.D. One Minute Sit-to-Stand Test as a Potential Triage Marker in COVID-19 Patients: A Pilot Observational Study. Trends Anaesth. Crit. Care 2021, 39, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.L.; Neves, I.; Luís, G.; Camilo, Z.; Cabrita, B.; Dias, S.; Ferreira, J.; Simão, P. Is the 1-Minute Sit-To-Stand Test a Good Tool to Evaluate Exertional Oxygen Desaturation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease? Diagnostics 2021, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, E. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak on the Cruise Ship Diamond Princess. Int. Marit. Health 2020, 71, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, T.; Kamiya, H.; Kakimoto, K.; Suzuki, M.; Wakita, T. Descriptive Study of COVID-19 Outbreak among Passengers and Crew on Diamond Princess Cruise Ship, Yokohama Port, Japan, 20 January to 9 February 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codreanu, T.A.; Ngeh, S.; Trewin, A.; Armstrong, P.K. Successful Control of an Onboard COVID-19 Outbreak Using the Cruise Ship as a Quarantine Facility, Western Australia, Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Hindu Net Desk. Coronavirus Updates | May 1, 2021. The Hindu. 2021. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-live-may-1-2021-updates/article34455434.ece (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Managing Investigations During an Outbreak. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/contact-tracing/contact-tracing-plan/outbreaks.html (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-classifications.html (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; He, D. The Disease Severity and Clinical Outcomes of the SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 775224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Considerations for Quarantine of Contacts of COVID-19 Cases: Interim Guidance, 19 August 2020; WHO/2019-nCoV/IHR_Quarantine/2020.3; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333901 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health; COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/overview/prioritization-of-therapeutics/ (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic Testing for SARS-CoV-2. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/diagnostic-testing-for-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ending Isolation and Precautions for People with COVID-19: Interim Guidance. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Goldberg, E.M.; Jiménez, F.N.; Chen, K.; Davoodi, N.M.; Li, M.; Strauss, D.H.; Zou, M.; Guthrie, K.; Merchant, R.C. Telehealth Was Beneficial during COVID-19 for Older Americans: A Qualitative Study with Physicians. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 3034–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Total Crew | Deck Crew | Engine Crew | Catering and Other Departments Crew |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 29 | 14 | 8 | 7 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 27 (93.1) | 14 (100) | 7 (87.5) | 6 (85.7) |

| Age years, median (IQR) | 43.1 (36.9,49.2) | 45.2 (37.3, 53.1) | 40.6 (34.4, 44.6) | 40.8 (39.8, 42.7) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), n (%) | ||||

| 18.5–24.9 | 10 (34.5) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (25) | 2 (28.6) |

| 25–29.9 | 13 (44.8) | 6 (42.9) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (57.1) |

| 30–34.9 | 6 (20.7) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (14.3) |

| Nationality, n (%) | ||||

| Ukrainian | 9 (31) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (50) | 0 |

| Polish | 9 (31) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (25) | 1 (14.3) |

| Filipino | 5 (17.2) | 0 | 0 | 5 (71.4) |

| Croatian | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 1 (14.3) |

| Norwegian | 1 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Indian | 1 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Russian | 1 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Spanish | 1 (3.4) | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 |

| Underlying disease, n (%) | ||||

| Asthma | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Vaccination, n (%) | ||||

| Received | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| RT-PCR for coronavirus, n(%) | ||||

| Detectable | ||||

| on arrival (n = 29) | 6 (20.7) | 6 (42.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Day 7 after quarantine (n = 23) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Day 14 after quarantine (n = 22) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Date | Activities | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1 May 2021 | The vessel departed from India. | - |

| 11 May 2021 | The vessel arrived at the Port of Songkhla in Singha Nakhon district. | |

| First RT-PCR tests performed (all crew, n = 29) | Detectable 6/29 (20.7%) | |

| 12 May 2021 | The Songkhla Provincial Health Office called for a joint meeting. | A joint working team was formed, and an action plan for COVID-19 control was implemented. |

| 13 May 2021 | Medicines and equipment were delivered to the vessel. | - |

| 14 May 2021 | Web application was started. | - |

| 19 May 2021 | Second RT-PCR tests performed (on CoCC, n = 23). | Detectable 1/23 (4.3%). No new CoCC found. |

| 20 May 2021 | Medicines were delivered. | - |

| 26 May 2021 | Third RT-PCR tests performed. | No new detectable result. |

| 2 June 2021 | The isolation of the last CoIC was completed. | - |

| 9 June 2021 | The COVID-19 control process ended. | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pongpattarapokin, R.; Chusri, S.; Ingviya, T.; Chaichulee, S.; Kwanyuang, A.; Horsiritham, K.; Varopichetsan, S.; Surasombatpattana, S.; Sathirapanya, C.; Sathirapanya, P.; et al. Teamwork Management and Benefit of Telemedicine in COVID-19 Outbreak Control on an Offshore Vessel in the Gulf of Thailand, Songkhla Province, Thailand: A Case Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105813

Pongpattarapokin R, Chusri S, Ingviya T, Chaichulee S, Kwanyuang A, Horsiritham K, Varopichetsan S, Surasombatpattana S, Sathirapanya C, Sathirapanya P, et al. Teamwork Management and Benefit of Telemedicine in COVID-19 Outbreak Control on an Offshore Vessel in the Gulf of Thailand, Songkhla Province, Thailand: A Case Report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105813

Chicago/Turabian StylePongpattarapokin, Rujjirat, Sarunyou Chusri, Thammasin Ingviya, Sitthichok Chaichulee, Atichart Kwanyuang, Kanakorn Horsiritham, Suebsai Varopichetsan, Smonrapat Surasombatpattana, Chutarat Sathirapanya, Pornchai Sathirapanya, and et al. 2023. "Teamwork Management and Benefit of Telemedicine in COVID-19 Outbreak Control on an Offshore Vessel in the Gulf of Thailand, Songkhla Province, Thailand: A Case Report" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105813