Abstract

In Canada, approximately 52% of First Nations, Inuit and Métis (Indigenous) peoples live in urban areas. Although urban areas have some of the best health services in the world, little is known about the barriers or facilitators Indigenous peoples face when accessing these services. This review aims to fill these gaps in knowledge. Embase, Medline and Web of Science were searched from 1 January 1981 to 30 April 2020. A total of 41 studies identified barriers or facilitators of health service access for Indigenous peoples in urban areas. Barriers included difficult communication with health professionals, medication issues, dismissal by healthcare staff, wait times, mistrust and avoidance of healthcare, racial discrimination, poverty and transportation issues. Facilitators included access to culture, traditional healing, Indigenous-led health services and cultural safety. Policies and programs that remove barriers and implement the facilitators could improve health service access for Indigenous peoples living in urban and related homelands in Canada.

1. Introduction

1.1. First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples

First Nations, Inuit and Métis (Indigenous) peoples are the recognized Indigenous peoples in Canada [1]. Each has their own colonial history, and there is diversity and relatedness within and between these distinct peoples [1].

1.2. The Migration of Indigenous People to Urban Areas

Indigenous peoples in Canada are becoming more urbanized, with the 2016 census highlighting that 52% of First Nations, 62.6% of Métis and 56.2% of Inuit peoples lived in urban areas [2]. From 2006 to 2016, the estimated number of Indigenous peoples living in urban areas increased by 59.7% [2].

Métis people have been living in and migrating to Canadian cities since the founding days of the Métis nation [3]. In 1951, amendments to the Indian Act repealed a law that limited the free movement of First Nations peoples off reserves, resulting in the migration of First Nations people to urban areas [4]. The Indian Act also contributed to First Nations women’s migration to cities because if a First Nations woman with status (formally recognised as a First Nations woman) married a non-status man, she would lose her status and therefore be unable to live on reserve; which forced many First Nations women to move to urban areas [5]. The federal government began to actively implement polices of Inuit relocation from traditional territories to permanent settlements in the Nunangat or southern urban centres during WWII [3,4,5]. Food insecurity and access to health care, housing, employment, and education have prompted the ongoing migration of Inuit people to urban centres [3,6].

1.3. Access to Health Services in Urban Areas of Canada

Compared to remote areas of Canada, urban centres have a higher per capita density of primary healthcare, mental health, social support and specialist health services. Despite this urban concentration of services, Indigenous peoples living in urban areas do not necessarily have better health care experiences and treatment outcomes compared to First Nations people living on reserves or Inuit people living on Nunangat. The First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) found that 21.3% of First Nations people living on-reserve reported not having a primary health care provider, and 9.6% reported unmet health needs in the previous 12 months [7]. In the urban city of Toronto, 37.4% of Indigenous people reported not having a primary health care provider, and 28.0% reported having unmet healthcare needs in the previous 12 months [8]. This highlights that some Indigenous peoples living in urban areas, despite living closer to a range of health services, are having difficulty accessing health care services or are choosing not to access these services.

1.4. Aim

This study aims to highlight the barriers Indigenous people experience and the facilitators that could improve access to health services among Indigenous peoples living in urban areas of Canada.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conducting the Review

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement [9] but is not registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The primary research question was the following: What are the barriers to and facilitators of access to health services for First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples living in urban areas of Canada?

2.2. Search Strategy

We searched the electronic databases Embase, Medline and Web of Science from 1 January 1981 to 30 April 2020 using the following MeSH terms and variations:

- (First Nations OR Inuit OR Métis OR Indigenous OR Aboriginal OR Native) AND

- (Canada) AND

- (Urban OR urbanized OR city OR cities OR metropolitan) AND

- (clinic OR medical OR doctor OR nurse OR physician OR primary health service OR mental health OR hospital OR drug use services) AND

- (access OR accessing)

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

Reference lists of included studies were examined for additional studies. We also searched for relevant grey literature including government or community reports using Google. Studies were included if they had a focus on First Nations (status or non-status), Inuit or Métis peoples who lived in urban areas of Canada and provided information about barriers or facilitators to accessing health services. Studies that reported combined results of Indigenous people living in urban and rural/remote settings were included if there was content specific to urban health care.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they were guidelines, reviews, opinion pieces, not in English, contained no Indigenous specific results, or the full paper could not be accessed electronically or through author communication. If a study met the inclusion criteria but it did not specify the distinct Indigenous nations included in the study (i.e., First Nations, Inuit or Métis) then the authors labelled the study population as ‘Indigenous’, recognizing that pan-Indigenous approaches that combine distinct Indigenous populations have limitations. In alignment with Statistics Canada, urban areas were defined as a population of ≥1000 and a population density of >400 persons/km [10].

2.5. Data Extraction

The first author reviewed each study using Covidence software [11] and removed studies that did not meet inclusion criteria. The first and second authors then worked together to reach consensus on the included studies. Data extraction was conducted by the first author and inserted into an excel spreadsheet [12]. The following information was extracted: author, year the study was published, years the study was conducted, city and province, Indigenous group (First Nations, Inuit, Métis), study design, how the sample was chosen, sample size, population group (adults, youth, Elders), type of health service (general practitioner, emergency department of a hospital, substance use service, dental clinic, etc.), incentives provided (cash, gift cards), aim of the study, barriers to health service access and facilitators to health service access.

2.6. Ethics

This study did not seek ethics approval because it used publicly available studies and government and community reports. It was reviewed and approved by the board of an Indigenous organization of which the third author is a senior staff member.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

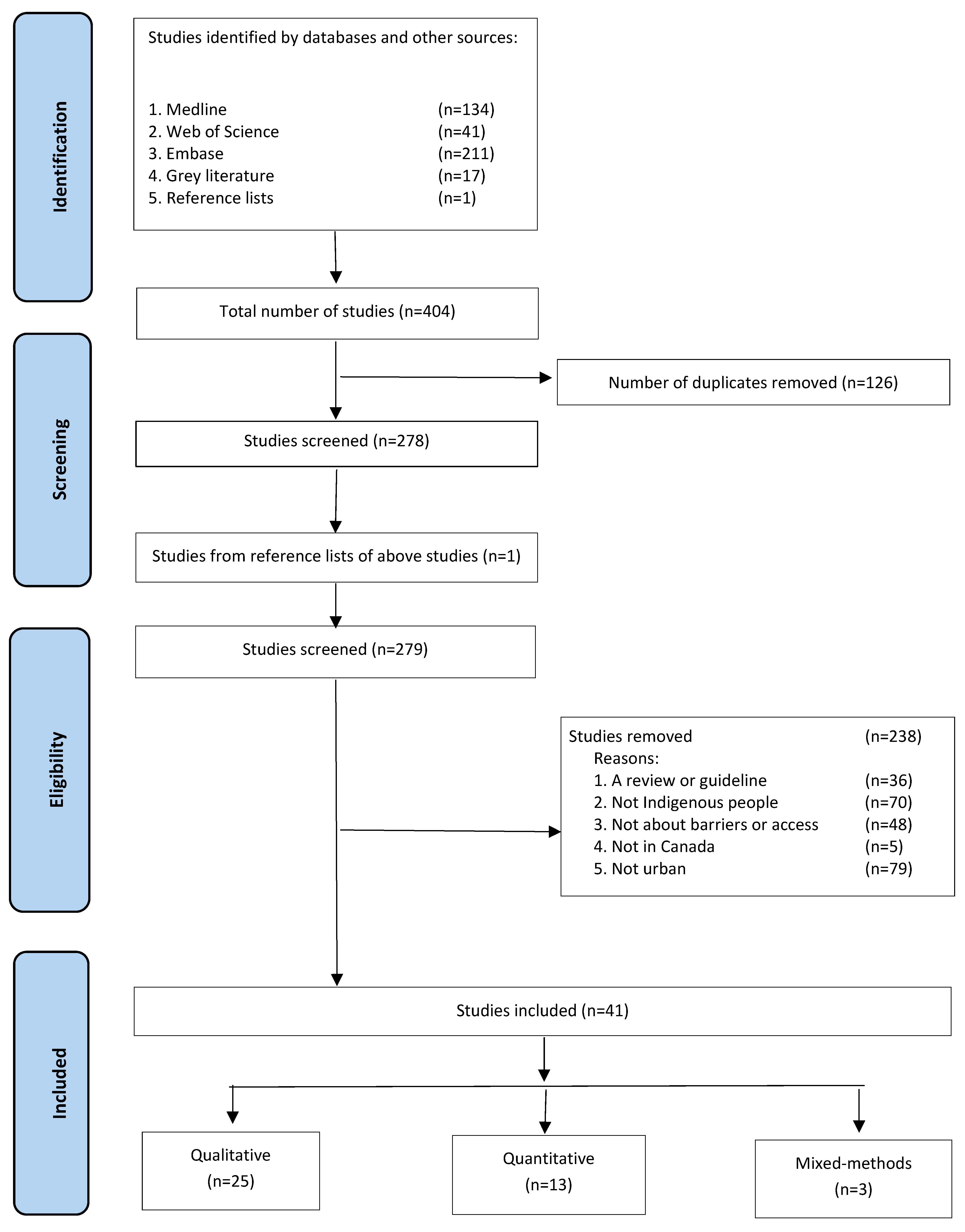

Overall, 41 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1 and Table 1) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies.

Table 1.

Studies examining health service access among First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples living in urban areas of Canada.

3.2. Barriers of Accessing Health Services

Barriers of accessing health care services for Indigenous peoples living in urban areas included difficult communication with health professionals, medication issues, dismissal by healthcare staff, wait times, mistrust and avoidance of healthcare, racial discrimination, poverty and transportation issues (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2.

Barriers and facilitators of accessing health services among First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples living in urban areas of Canada.

3.2.1. Difficult Communication with Health Care Professionals

Difficult communication with hospital staff was highlighted as a barrier [28,37,41,43,52,53]. Participants gave examples of when they were in medical facilities and not listened to, not believed or spoken to in a condescending manner [28,35,42]. Some participants spoke of not understanding what the healthcare providers were saying to them. When a family member accompanied one participant to the hospital, the participant said the following:

This time it was not as bad because my daughter came with me. I felt I was treated alright… I felt this time around the staff treated me good and this time I understand as the doctor talked slow to me and when I don’t understand the question I asked him to explain it to me better. I feel more comfortable now.[53]

One participant who was pregnant felt she did not have time to ask questions and said the following:

The doctor himself is so abrasive—flies into the room, does what he needs to do … it doesn’t really seem like he cares, and he is out the door and on to the next patient. … I feel so rushed that I don’t actually get to talk about things that are pertinent to my pregnancy. And so I leave the office and did not voice my concerns.[27] (p. 5)

Finally, one study highlighted a fear that disclosing spiritual gifts to non-Indigenous healthcare providers could bring about a mental health misdiagnosis [25], suggesting that Indigenous patients may not feel safe disclosing traditional cultural practices to healthcare providers.

3.2.2. Medication Issues

Some participants who had a history of substance use were denied medications for telling the truth about their substance use [20,34,35]. Two studies which included people who used illicit drugs highlighted that when they told the truth about their drug use, they were kicked out of the doctor’s office or were told that they needed a clean urine test before they could receive their medications [20,35]. A non-Indigenous nurse acknowledged that “there is a systemwide belief that Indigenous peoples misuse pain medications, and as a result, Indigenous peoples are not provided adequate pain medication” [48] (p. 43).

One study participant stated that her doctor did not know that she should go on medication for her condition, and she had to educate him [33]. There was an example of fear towards being overprescribed medications with one participant reporting that they were terrified of medication due to seeing a family member being heavily medicated because of mental health issues [25].

3.2.3. Dismissal or Discharge by Healthcare Staff

Indigenous people living in urban areas described being either verbally or physically dismissed from healthcare facilities and how this affected their ability to access healthcare including instances where they avoided/delayed seeking healthcare until they were very sick. Examples of dismissal include being threatened by hospital security or being involuntarily discharged from the hospital [16,20]. One participant said the following:

My pneumonia hadn’t even [gone away] and it was during winter time. And …one of the nurses came in and said the doctor is discharging you. I said I’m not even better yet and she said, well it’s time for you to go … don’t let me call security. And sure enough she called security. Security literally came in, grabbed me behind my arms, dragged me down the hallways and threw me out the door, with pneumonia, in winter time.[16] (p. 1112)

3.2.4. Wait Times

Studies highlighted that Indigenous people spend a lot of time waiting for healthcare services. Participants in Barnabe and colleagues’ (2017) study said that they had difficulty having the physician make a referral, obtaining an appointment once referred and waiting too long to see the referral physician as the referral appointments were often cancelled or deferred. Other participants reported that there were long wait lists to access healthcare in general, long waiting times once they were in the doctor’s office or emergency room and long waits for test results [19,27,33,34,42,49,53]. Another participant, highlighted how long waiting times discouraged them from seeking timely assessment:

I notice every time I go see a doctor, I’m waiting for a long time. Like my knee, I handled that for about a week and a half before I even decided to go [for treatment] because I knew the waiting time was just going to be a long time.[42] (p. 705)

3.2.5. Mistrust and Avoidance of Healthcare

Studies highlighted the mistrust that urban Indigenous people felt towards the health care system [53]. Previous experiences of accessing health services contribute to Indigenous mistrust of healthcare providers [19,34]. One Indigenous Elder from Schill and colleagues’ (2019) study commented that

Sometimes we don’t trust the doctors … because we don’t know what they’re going to give us. And sometimes that can harm our body … That’s why when I was smoking and I was coughing for three days, I didn’t go to the hospital because I’m scared of hospitals. Sometimes it’s trust.[39] (p. 871)

3.2.6. Racial Discrimination

Studies identified racial discrimination as a barrier to accessing health services [15,29,30,39,41,43,48]. One study interviewed health care providers about Indigenous patients with one healthcare professional stating that “there are times when Indigenous patients come in with expectations of poor treatment, which sets the stage for a challenging interaction” [49]. A doctor also said, “as a physician, sometimes I become defensive when an interaction with an Indigenous patient is not going well” [48] (p. 40). Health professionals acknowledged their lack of understanding of Indigenous issues and culture, and that their views about Indigenous people were informed by the media.

Participants highlighted that being Indigenous elicited anti-Indigenous discrimination [20,37,41,52]. One participant noted that

The healthcare workers treated me like crap and I know it was because I was Native … When you need the medical care we put up with it. We shouldn’t have to.[20]

Studies highlighted the harms that discrimination can have on an individual’s health-seeking behaviours [18,40]. The Our Health Counts Toronto study found that 71% of Indigenous adults living in Toronto reported experiencing racism from healthcare professionals which then prevented, stopped or delayed them from returning to seek healthcare [45].

3.2.7. Poverty and Transportation

Poverty was identified as a barrier even within Canada’s universal health care system [16,19,20,37,43,49,52].

Indigenous peoples were concerned with how healthcare providers might be responding to them based on their appearance as people living in poverty and poor neighbourhoods [16,52].

One participant noted that

… you have to expect living in this area you’re not going to get the best healthcare. It seems like they care less when you‘re in a poverty-stricken area … the doctor’s office is kind of ghetto looking … It doesn’t feel personable, it doesn’t feel welcoming, and it feels like you’re in and out, and they are not doing their job. They don’t ask you how you’re doing, as they would in a different nicer area.[47]

Poverty also includes not being able to afford to take transportation to medical appointments and was mentioned in four studies [19,27,46,52]. One study interviewed an Indigenous pregnant woman who noted that

“I was supposed to go for an ultrasound, but I couldn’t go. It was cold that day and I wasn’t gonna walk. I didn’t have a bus fare … didn’t want to freeze my ears, so I just stayed home”.[27]

3.3. Facilitators of Accessing Health Services

The facilitators to accessing health care were access to culture, traditional healing, Indigenous-led healthcare services and support around their needs such as food and transportation (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

3.3.1. Access to Culture

The opportunity to use and practice culture was highly valued by Indigenous peoples living in urban areas [13,14,22,25,36]. One participant reported that, “to have wellness, it means having access to your culture and to resources and support” [25] (p. 94). Community-designed teachings, traditional healing services, services in different Indigenous languages (e.g., Oji-Cree, Cree, Inuktitut, Ojibway), medicine walks, dancing, drumming, traditional arts and crafts, sweat lodges and ceremonies were available and highly valued as part of their healthcare [13,14]. Access to and use of traditional languages was also identified in several studies as a facilitator of healthcare access [13,14,22,44].

There was recognition of mainstream medicine and its benefits, but this was commonly in a context in which participants identified that they had access to both mainstream and traditional Indigenous health and wellbeing practices (e.g., naturopaths, social workers) [36]. One participant remarked that

“I do see a clinical counsellor every couple of weeks but I don’t see that as being more helpful than going to the beading group, than going to Métis Night at the Friendship Centre”.[25] (p. 95)

3.3.2. Traditional Healing

Access to traditional healing was identified as highly important in multiple studies. The personal connection with Traditional Healers was cherished by Indigenous people in these studies [13,17,23,36]. One Indigenous person noted that

Doctors today don’t know who we are, especially when we are using walk-in clinics. Our traditional doctors knew us, they knew our family, and they talked to our ancestors in ceremony. If we got sick, our parents knew where to go, and not just to one person, there were different people in the community.[36] (p. e395)

3.3.3. Indigenous-Led and Run Health Services

Grey literature provided valuable information regarding Indigenous community-led and -run health services. These services improved access and connection to traditional healing alongside mainstream medical services [14,24,43]. A report by the Health Council of Canada (2012) described a range of projects designed and based in Indigenous communities. One example was Clinique Minowe which began in 2011 and included a nurse and a social worker providing home visits. Within the two years, the program significantly increased access of a broad range of health, social services and programs. Staff built trust through a visible and active presence in the community. Families who have an established relationship with Clinique Minowe were more likely to attend their western medical or social service appointments compared to before the clinic was set up [24].

Studies described the higher quality of care at Indigenous-led and -run health services [39,44,46,51]. One participant commented that

I went to another downtown clinic and the doctor that I had was giving me constantly the same pills all the time when I was getting sick. I went over to the Native Health and the doctor there, as soon as she saw me, said, ‘Get to the hospital.’ And now she is my doctor. She is somebody who cares and takes the time to listen to me.[51] (p. 826)

3.3.4. Access to Culturally Safe Care

Cultural safety was identified as a high priority that increased access, including return visits to health services, especially in one study where a participant said the following:

I think that I have to mention cultural safety. It’s so important. It’s something that should be a way of being for everyone, so that we can develop respectful relationships with no matter who it is. […] If I know where our people are, like the Ki-Low-Na Friendship Society, I’d rather go there.[39] (p. e827)

4. Discussion

This study highlights the main barriers to health services for Indigenous people living in urban areas and identified facilitators that could improve Indigenous people accessing health services. Although this study focused on the perspectives and experiences of Indigenous peoples, there was one study that included the perspectives of health professionals when providing services to Indigenous peoples in urban areas.

Only one study focused on Métis peoples [25] and Inuit peoples [43], respectively. Additional studies that included Métis and Inuit peoples also included First Nations peoples. Just under half of the studies in our analysis included First Nations peoples only. The three distinct Indigenous groups seemed to face similar challenges of racial discrimination and negative interactions with health professionals. This highlights the need for increased education among health professionals about the three distinct Indigenous groups in Canada.

Studies described tensions between Indigenous peoples and health professionals. The organizational practices within institutions such as hospitals and primary health services can impact health professionals’ behaviour towards Indigenous people. In recent years Indigenous leaders and communities have advocated for health institutions to implement cultural safety training with their staff. Cultural safety is a concept developed by Māori nurse Irihapeti Ramsden in the 1990s in response to the way Māori people were being treated by health institutions [54,55]. Her work proposes three steps towards culturally safe practices: firstly, cultural awareness or understanding of differences; secondly, cultural sensitivity where people accept the legitimacy of difference; and thirdly, reflecting on the impact of the service provider’s life experience and positioning on others. In Canada, a team in Montreal implemented cultural safety training with 45 nurses, social workers and doctors. The program was successful at raising awareness of Indigenous culture and challenges Indigenous peoples face when accessing health services, the importance of including Elders in the design and delivery of services and to decolonize health care systems [56]. Similar to New Zealand and Canada, Indigenous leaders in Australia have advocated for cultural safety training. A report by McDermott and colleagues highlights why institutions should imbed cultural safety as an ongoing program for all health care staff to reduce racism, raise awareness and increase access to health services for Indigenous peoples [57]. A review in Australia found that the large disparity in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people could be attributed to institutional racism and intergenerational trauma [58,59]. From an institutional perspective, cultural safety training may provide a step forward to improving Indigenous peoples experiences with health professionals.

In our review, the study by Wylie and colleagues (2019) suggests that stereotypes within the health profession regarding Indigenous peoples set the stage for challenging interactions. This aligns with literature that highlights “cultural differences”; nurses ‘othering’ Indigenous peoples; and assumptions about Indigenous peoples that influenced clinical practice [60,61]. The cultural safety approach taken by Indigenous leaders in Canada, Australia and New Zealand could provide some useful ways health care institutions could reduce racism and increase access to health services for racial minorities in these developed nations. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service is attempting to reduce challenges black and Asian populations face when accessing the National Health Service (the United kingdom’s universal health system). Using the approaches Indigenous leaders have taken may provide a starting point to developing similar cultural safety training to achieve these reductions in discrimination and raise awareness [62].

Access to Indigenous-led and -run health services was highly valued by Indigenous peoples. These community-based health services are commonly rooted in Indigenous ways of knowing and doing; Indigenous community, identity and inclusion; and Indigenous culture and cultural protocols—all of which can contribute to cultural safety. Two studies highlighted the importance of these more inclusive ways of approaching health and wellbeing and linked implementation strategies including equity-focused organizational structures, policies and processes; contextually tailored care; and culturally safe spaces for Indigenous patients [44,52].

Holistic healthcare that includes a person’s emotional, mental and physical wellbeing was identified as important to Indigenous peoples [13,14,43]. The concept of holistic healthcare and wellbeing has been widely acknowledged as having benefits [58]. There is some evidence supporting the benefits of holistic wellbeing programs, particularly for Indigenous peoples who have spent time in prison and then re-enter the community [63]. Continued efforts to look beyond the one health issue for which an individual is attending a health service are needed. This indirectly results in other health conditions being identified early even though the patient may not have attended the health care service for that health issue. Programs in Australia that provide financial incentives to Indigenous health service providers upon completion of general preventative “health checks” have shown good uptake [64]. These adult health checks aim to advance the wellbeing of Indigenous peoples in Australia by conducting a range of general health checks to identify any health issue early and commence a plan to address it. This could be one way to provide holistic healthcare in Canada.

Access to traditional healing was also of high importance among Indigenous participants [13,14,32,37,43]. A study by Hossain et al. (2020) found that having a strong connection to your Indigenous culture seemed to have health benefits. A review by Asamoah and colleagues highlighted that in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, traditional healing was used in three ways: firstly, as the main choice of treatment; secondly, as an add-on option to western medical treatment; and thirdly, through adopting traditional knowledge within mainstream health care institutions [65]. This suggests that Indigenous people who move to urban areas for a range of reasons might benefit from connecting to Indigenous culture and with other Indigenous people living in urban areas.

4.1. Limitations

Limitations include quantitative studies that, while providing useful information, were not constructed to provide in-depth information regarding barriers and facilitators [19,29,30,46,49,52].

4.2. Future Research

There is a need for longer-term funding of Indigenous-led healthcare services and Indigenous child and youth services [41,45]. Funding is needed both for healthcare institutions to collaborate with Indigenous organizations and peoples to design and implement cultural training and for Indigenous organizations and peoples to evaluate these cultural safety programs. It is also important to provide continuing cultural awareness and education opportunities for non-Indigenous healthcare workers [29].

Future research needs to also advance Indigenous-led health information infrastructure for Indigenous peoples living in urban areas. For example, the various Our Health Counts studies have demonstrated limitations in estimating the true number of Indigenous peoples living in urban areas [66]. One component of this work includes linking cohorts of Indigenous peoples living in urban areas to provincial healthcare utilization datasets to address gaps in population-based information regarding healthcare usage. Regular reporting of primary and tertiary healthcare use for Indigenous peoples is essential to identify service gaps and to identify ways to reduce emergency room visits and hospitalizations. This work should be Indigenous-led and focus on the research questions that the community wants answered. Smylie and colleagues (2011) noted that “self-determination is fundamental and thus [Indigenous] peoples must have full involvement and choice in all aspects of health care delivery, including governance, research, planning and development, implementation and evaluation” [41] (p. 82).

Future research that examines the barriers Two-Spirit peoples face when accessing healthcare and the barriers and facilitators to healthcare for Indigenous Elders living in urban areas is also needed [22].

5. Conclusions

Indigenous people living in urban areas are experiencing barriers in healthcare access. A history of discrimination is negatively influencing interactions between non-Indigenous health professionals and Indigenous peoples. Practical ways to implement the facilitators is a way forward to increasing access. Indigenous-led research that meets community needs should be encouraged. Additionally, providing and evaluating cultural safety and awareness training to non-Indigenous healthcare providers is needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph20115956/s1, Table S1: Barriers and facilitators of accessing health care among First Nation, Métis and Inuit peoples in urban areas of Canada.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and N.M.M.; methodology, S.G. and N.M.M.; validation, S.G. and N.M.M.; formal analysis, S.G. and N.M.M.; investigation, S.G. and N.M.M.; data curation, S.G. and N.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G., N.M.M. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, S.G., N.M.M., J.S. and J.W.F.; funding acquisition, S.G. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author was able to travel to Toronto to collaborate with the other authors through a University of Melbourne Dyason fellowship (number: 604426). The first author’s salary is supported by an Australian National Health & Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (number: 2009727). The last author is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Advancing Generative Health Services for Indigenous Populations in Canada (number: 950232638).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not receive ethical approval as it is a systematic review of published studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not obtained because this is a systematic review of published studies.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

All authors are Indigenous peoples and would like to acknowledge the important role Indigenous people have in leading, designing and implementing health services for and with Indigenous communities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Canadian Geographic. Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. 2020. Available online: https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/section/truth-and-reconciliation/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Key Results from the 2016 Census. 2017. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Dickason, O.P.; Newbigging, W. A Concise History of Canada’s First Nations. 2015. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/concise-history-of-canadas-first-nations/oclc/895341415 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples. Relocation of Aboriginal Communities. In Report on the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples; Indian and Northern Affairs: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1991; Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100014597/1572547985018 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. Understanding the Needs of Urban Inuit Women. 2017. Available online: https://pauktuutit.ca/project/understanding-the-needs-of-urban-inuit-women-final-report/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Patrick, D.; Tomiak, J.A.; Brown, L.; Langille, H.; Vieru, M. Regaining the Childhood I Should Have Had: The Transformation of the Inuit. In Aboriginal Peoples in Canadian Cities: Transformation and Continuities; Howard, H., Proulx, C., Eds.; Wilfred Laurier University Press: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. National Report of the First Nations Regional Health Survey Phase 3: Volume One. 2018. Available online: https://niagaraknowledgeexchange.com/resources-publications/first-nations-regional-health-survey-phase-3-volume-1-2/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- O’Brien, X.; Wolfe, S.; Maddox, R.; Laliberte, N.; Smylie, J. Adult Access to Health Care—Our Health Counts Toronto. 2018. Available online: http://www.welllivinghouse.com/what-we-do/projects/our-health-counts/our-health-counts-toronto/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/subjects/standard/pc (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Harrison, H.; Griffin, S.J.; Kuhn, I.; Usher-Smith, J.A. Software Tools to Support Title and Abstract Screening for Systematic Reviews in Healthcare: An Evaluation. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Wilson, K. Microsoft Excel 2013. In Using Office 365; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboriginal Health Access Centres. Bringing Order to Indigenous Primary Health Care Planning and Delivery in Ontario. 2016. Available online: https://iportal.usask.ca/record/59345 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Aboriginal Health Access Centres; Aboriginal Community Health Centres. Our Health, Our Seventh Generation, Our Future. 2015. Available online: https://soahac.on.ca/our-health-our-seventh-generation-our-future-2015-aboriginal-health-access-centres-report/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Carter, A.; Greene, S.; Nicholson, V.; Dahlby, J.; Pokomandy, A.; Loutfy, M.R. “You Know Exactly Where You Stand in Line. Its Right at the Very Bottom of the List”: Negotiating Place and Space among Women Living with HIV Seeking Health Care in British Columbia, Canada. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 25 (Suppl. SA), 25A–26A. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, J.; Varcoe, C.; Browne, A.J. Aboriginal Women’s Experiences of Accessing Health Care When State Apprehension of Children Is Being Threatened. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environics Institute. Urban Aboriginal Peoples Study. 2010. Available online: https://www.uaps.ca/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Firestone, M.; Smylie, J.; Maracle, S.; McKnight, C.; Spiller, M.; O’Campo, P. Mental Health and Substance Use in an Urban First Nations Population in Hamilton, Ontario. Can. J. Public Health 2015, 106, e375–e381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.; Smylie, J.; Maracle, S.; Spiller, M.; O’Campo, P. Unmasking Health Determinants and Health Outcomes for Urban First Nations Using Respondent-Driven Sampling. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Fleming, K.; Markwick, N.; Morrison, T.; Lagimodiere, L.; Kerr, T. “They Treated Me like Crap and I Know It Was Because I Was Native”: The Healthcare Experiences of Aboriginal Peoples Living in Vancouver’s Inner City. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Snyder, M.; Wilson, K.; Whitford, J. Healthy Spaces: Exploring Urban Indigenous Youth Perspectives of Social Support and Health Using Photovoice. Health Place 2019, 56, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Council of Canada. Compendium of Promising Practices: Understanding and Improving Aboriginal Maternal and Child Health in Canada. 2003. Available online: https://childcarecanada.org/documents/research-policy-practice/11/08/understanding-and-improving-aboriginal-maternal-and-child (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Health Council of Canada. Canada’s Most Vulnerable: Improving Health Care for First Nations, Inuit, and Metis Seniors. 2013. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/458307/publication.html (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Health Council of Canada. Empathy, Dignity, and Respect: Creating Cultural Safety for Aboriginal People in Urban Health Care. 2012. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.698021/publication.html (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Auger, M.D. “We Need to not Be Footnotes Anymore”: Understanding Metis People’s Experiences with Mental Health and Wellness in British Columbia, Canada. Public Health 2019, 176, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaman, M. Evaluation of the Partners in Inner-City Integrated Prenatal Care (PIIPC) Project in Winnipeg, Canada: Perspectives of Women and Health Care Providers. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54 (Suppl. 1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaman, M.I.; Sword, W.; Elliott, L.; Moffatt, M.; Helewa, M.E.; Morris, H.; Gregory, P.; Tjaden, L. Barriers and Facilitators Related to Use of Prenatal Care by Inner-City Women: Perceptions of Health Care Providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, R.D.; Evans, M.; Berg, L.D.; Bottorff, J.L.; Dingwall, C.; Alexis, C.; Nyberg, J.; Smith, M.L. Visibility and Voice: Aboriginal People Experience Culturally Safe and Unsafe Health Care. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1662–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitching, G.T.; Firestone, M.; Schei, B.; Wolfe, S.; Bourgeois, C.; O’Campo, P.; Rotondi, M.; Nisenbaum, R.; Maddox, R.; Smylie, J. Unmet Health Needs and Discrimination by Healthcare Providers among an Indigenous Population in Toronto, Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, H.P.; Cidro, J.; Isaac-Mann, S.; Peressini, S.; Maar, M.; Schroth, R.J.; Gordon, J.N.; Hoffman-Goetz, L.; Broughton, J.R.; Jamieson, L. Racism and Oral Health Outcomes among Pregnant Canadian Aboriginal Women. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27 (Suppl. 1), 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyola-Sanchez, A.; Hazlewood, G.; Crowshoe, L.; Linkert, T.; Hull, P.M.; Marshall, D.; Barnabe, C. Qualitative Study of Treatment Preferences for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Pharmacotherapy Acceptance: Indigenous Patient Perspectives. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaskill, D.; FitzMaurice, K.; Cidro, J. Toronto Abgoriginal Research Project. 2011. Available online: https://tarp.indigenousto.ca/about-toronto-aboriginal-research-project-tarp/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Mill, J.E.; Jackson, R.C.; Worthington, C.A.; Archibald, C.P.; Wong, T.; Myers, T.; Prentice, T.; Sommerfeldt, S. HIV Testing and Care in Canadian Aboriginal Youth: A Community Based Mixed Methods Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, S.E.; Wilson, K. Understanding Barriers to Health Care Access through Cultural Safety and Ethical Space: Indigenous People’s Experiences in Prince George, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 218, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowgesic, E.; Meili, R.; Stack, S.; Myers, T. The Indigenous Red Ribbon Storytelling Study: What Does It Mean for Indigenous Peoples Living with HIV and a Substance Use Disorder to Access Antiretroviral Therapy in Saskatchewan? Can. J. Aborig. Commu.-Based HIV/AIDS Res. 2015, 7, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, M.; Howell, T.; Gomes, T. Moving toward Holistic Wellness, Empowerment and Self-Determination for Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Can Traditional Indigenous Health Care Practices Increase Ownership over Health and Health Care Decisions? Can. J. Public Health 2016, 107, e393–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Xavier, C.; Kitching, G.; Maddox, R.; Muise, G.M.; Dokis, B.; Smylie, J. Adult Access to Health Care Findings, Access to Health Care Findings & Community Priorities. Our Health Counts London. 2016. Available online: https://soahac.on.ca/our-health-counts/#:~:text=Our%20Health%20Counts%20is%20a,Well%20Living%20House%20at%20St (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Pearce, M.E.; Jongbloed, K.; Demerais, L.; MacDonald, H.; Christian, W.M.; Sharma, R.; Pick, N.; Yoshida, E.M.; Spittal, P.M.; Klein, M.B. “Another Thing to Live for”: Supporting HCV Treatment and Cure among Indigenous People Impacted by Substance Use in Canadian Cities. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 74, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, K.; Terbasket, E.; Thurston, W.E.; Kurtz, D.; Page, S.; McLean, F.; Jim, R.; Oelke, N. Everything Is Related and It All Leads Up to My Mental Well-Being: A Qualitative Study of the Determinants of Mental Wellness Amongst Urban Indigenous Elders. Br. J. Soc. Work 2019, 49, 860–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smye, V.; Browne, A.J.; Varcoe, C.; Josewski, V. Harm Reduction, Methadone Maintenance Treatment and the Root Causes of Health and Social Inequities: An Intersectional Lens in the Canadian Context. Harm Reduct. J. 2011, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smylie, J.; Firestone, M.; Cochran, L.; Prince, C.; Maracle, S.; Morley, M.; Mayo, S.; Spiller, T.; McPherson, B. Our Health Counts Hamilton. 2011. Available online: http://www.welllivinghouse.com/what-we-do/projects/our-health-counts/our-health-counts-hamilton/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Tang, S.Y.; Browne, A.J.; Mussell, B.; Smye, V.L.; Rodney, P. “Underclassism” and Access to Healthcare in Urban Centres. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tungasuvvingat Inuit. Our Health Counts—Urban Indigenous Health Database Project—Inuit Adults Living in Ottawa. 2017. Available online: https://tiontario.ca/resources (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Van Herk, K.A.; Smith, D.; Tedford Gold, S. Safe Care Spaces and Places: Exploring Urban Aboriginal Families’ Access to Preventive Care. Health Place 2012, 18, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well Living House. Discrimination Factsheet, Our Health Counts Toronto. 2016. Available online: http://www.welllivinghouse.com/what-we-do/projects/our-health-counts/our-health-counts-toronto/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Barnabe, C.; Lockerbie, S.; Erasmus, E.; Crowshoe, L. Facilitated Access to an Integrated Model of Care for Arthritis in an Urban Aboriginal Population. Can. Fam. Physician 2017, 63, 699–706. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.L.; Jack, S.M.; Ballantyne, M.; Gabel, C.; Bomberry, R.; Wahoush, O. Indigenous Mothers’ Experiences of Using Primary Care in Hamilton, Ontario, for Their Infants. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2019, 14, 1600940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, L.; McConkey, S. Insiders’ Insight: Discrimination against Indigenous Peoples through the Eyes of Health Care Professionals. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, M.; Firestone, M.A.; McKnight, C.D.; Smylie, J.; Rotondi, M.A. A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Relationship between Diabetes and Health Access Barriers in an Urban First Nations Population in Canada. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, A.C.; Cotnam, J.; O’Brien-Teengs, D.; Greene, S.; Beaver, K.; Zoccole, A.; Loutfy, M. Racism Experiences of Urban Indigenous Women in Ontario, Canada: “We All Have That Story That Will Break Your Heart”. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2019, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, C.; Carroll, D.; Chaudhry, M. In Search of a Healing Place: Aboriginal Women in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J.; Smye, V.L.; Rodney, P.; Tang, S.Y.; Mussell, B.; O’Neil, J. Access to Primary Care from the Perspective of Aboriginal Patients at an Urban Emergency Department. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, B.L.; Carmargo Plazas, M.D.P.; Salas, A.S.; Bourque Bearskin, R.L.; Hungler, K. Understanding Inequalities in Access to Health Care Services for Aboriginal People: A Callfor Nursing Action. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2014, 37, E1–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsden, I. Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. 2002. Available online: https://www.nccih.ca/634/cultural_safety_and_nursing_education_in_aotearoa_and_te_waipounamu.nccih?id=1124 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yaphe, S.; Richer, F.; Martin, C. Cultural Safety Training for Health Professionals Working with Indigenous Populations in Montreal, Quebec. Int. J. Indig. Health 2019, 14, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, D. Having the Hard Conversations: Strengthening Pedagogical Effectiveness by Working with Student and Institutional Resistance to Indigenous Health Curriculum. 2020. Available online: https://limenetwork.net.au/resources-hub/resource-database/having-the-hard-conversations-strengthening-pedagogical-effectiveness-by-working-with-student-and-institutional-resistance-to-indigenous-health-curriculum-final-report/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/110ef308-c848-4537-b0e7-6d8c53589194/aihw-aus-221-chapter-6-2.pdf.aspx (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Kelaher, M.A.; Ferdinand, A.S.; Paradies, Y. Experiencing Racism in Health Care: The Mental Health Impacts for Victorian Aboriginal Communities. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 201, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, A.J. Clinical Encounters between Nurses and First Nations Women in a Western Canadian Hospital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J. Discourses Influencing Nurses’ Perceptions of First Nations Patients. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 41, 166–191. [Google Scholar]

- Lokugamage, A.U.; Rix, E.; Fleming, T.; Khetan, T.; Meredith, A.; Hastie, C.R. Translating Cultural Safety to the UK. J. Med. Ethics 2021, 49, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P.; Lloyd, J.E.; Joshi, C.; Malera-Bandjalan, K.; Baldry, E.; McEntyre, E.; Sherwood, J.; Reath, J.; Indig, D.; Harris, M.F. Do Programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Leaving Prison Meet Their Health and Social Support Needs? Aust. J. Rural Health 2018, 26, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormel, H.; Kok, M.; Kane, S.; Ahmed, R.; Chikaphupha, K.; Rashid, S.F.; Gemechu, D.; Otiso, L.; Sidat, M.; Theobald, S.; et al. Salaried and Voluntary Community Health Workers: Exploring How Incentives and Expectation Gaps Influence Motivation. Jum Resour Health 2019, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, G.; Khakpour, M.; Carr, T.; Groot, G. Exploring Indigenous Traditional Healing Programs in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand: A Scoping Review. Explore 2023, 19, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, M.A.; O’Campo, P.; O’Brien, K.; Firestone, M.; Wolfe, S.H.; Bourgeois, C.; Smylie, J.K. Our Health Counts Toronto: Using Respondent-Driven Sampling to Unmask Census Undercounts of an Urban Indigenous Population in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).