Job Seekers’ Burnout and Engagement: A Qualitative Study of Long-Term Unemployment in Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Unemployment in the Psychological Perspective

1.2. Job Burnout

1.3. The Burnout of Unemployed Job Seekers

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Instruments

- -

- Engagement) What makes you feel energetic when looking for work?

- -

- (Exhaustion) What makes you feel exhausted when looking for work?

- -

- (Involvement) What makes you feel involved in your job search?

- -

- (Cynicism) What makes you feel detached in your job search?

- -

- (Search effectiveness) What makes you feel effective in your job search?

- -

- (Search ineffectiveness) What makes you feel ineffective in your job search?

2.3. Participants

2.4. Ethical Issues

2.5. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat. Total Unemployment Rate. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00203/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Eurostatistics. Labour Market. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/euro-indicators/labour-market (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2023. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_865332.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Consob. La Crisi da COVID-19—Le Misure a Sostegno Dell’economia in Europa e in Italia. Available online: https://www.consob.it/web/investor-education/crisi-misure-sostegno (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Ministero del Lavoro. Decreto Sostegni: Numerose Novità in Materia di Lavoro. Available online: https://www.lavoro.gov.it/notizie/Pagine/Decreto-Sostegni-numerose-novita-in-materia-di-lavoro.aspx (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Chirumbolo, A.; Callea, A.; Urbini, F. The Effect of Job Insecurity and Life Uncertainty on Everyday Consumptions and Broader Life Projects during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcover, C.-M.; Salgado, S.; Nazar, G.; Ramirez-Vielma, R.; Gonzalez-Suhr, C. Job Insecurity, Financial Threat, and Mental Health in the COVID-19 Context: The Moderating Role of the Support Network. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221121048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckerman, P.; Ilmakunnas, P. Unemployment and self-assessed health: Evidence from panel data. Health Econ. 2009, 18, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, E.; Böckerman, P.; Lundqvist, A. Self-reported health versus biomarkers: Does unemployment lead to worse health? Public Health 2020, 179, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez-Coto, M.; Rute-Pérez, S.; Pérez-García, M.; Caracue, A. Unemployment and general cognitive ability: A review and meta-analysis. J. Econ. Psychol. 2021, 87, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrish, N.; Medina-Lara, A. Does unemployment lead to greater levels of loneliness? A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 287, 114339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Hörmann, G.; Heipertz, W. Unemployment and health—A public health perspective. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2007, 104, A2957–A2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee-Ryan, F.M.; Song, Z.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kinicki, A.J. Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, K.A. Job loss and unemployment research from 1994 to 1998: A review and recommendations for research and intervention. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 55, 188–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossen, C.; McIlveen, P. Unemployment from the perspective of the psychology of working. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 34–79. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R.D.; Diemer, M.A.; Perry, J.C.; Laurenzi, C.; Torrey, C.L. The construction and initial validation of the Work Volition Scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now Positive Psychological Capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, M.D.; Privado, J.; Arnaiz, R. Is there any relationship between unemployment in young graduates and psychological resources? An empirical research from the Conservation of Resources Theory. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2019, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Valera, M.M.; Soler-Sánchez, M.I.; García-Izquierdo, M.; Meseguer de Pedro, M. Personal psychological resources, resilience and self-efficacy and their relationship with psychological distress in situations of unemployment. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 34, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.K.G.; Chen, D.; Aw, S.S.Y.; Tan, M.Z. Unemployed and exhausted? Job-search fatigue and reemployment quality. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 92, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P.; Schaufeli, W.B. Measuring burnout. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well-Being; Cooper, C.L., Cartwright, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 86–108. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f129180281 (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Nadon, L.; De Beer, L.T.; Morin, A.J.S. Should Burnout Be Conceptualized as a Mental Disorder? Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout: A short socio-cultural history. In Burnout, Fatigue, Exhaustion; Neckel, S., Schaffner, A., Wagner, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Canu, I.G.; Marca, S.C.; Dell’Oro, F.; Balázs, A.; Bergamaschi, E.; Besse, C.; Bianchi, R.; Bislimovska, J.; Bjelajac, A.K.; Bugge, M.; et al. Harmonized definition of occupational burnout: A systematic review, semantic analysis, and Delphi consensus in 29 countries. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2020, 47, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands-Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Desart, S.; De Witte, H. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, Validity, and Reliability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Turunen, J. The relative importance of various job resources for work engagement: A concurrent and follow-up dominance analysis. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2021, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Applying the Job Demands-Resources model: A ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organ. Dyn. 2017, 46, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, M.D.; Tsitouri, E. Positive psychology in the working environment. Job demands-resources theory, work engagement and burnout: A systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1022102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Upadyaya, K. Role of demands-resources in work engagement and burnout in different career stages. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 108, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, L.V.; Heinemann, T. Burnout: From work-related stress to a cover-up diagnosis. In Burnout, Fatigue, Exhaustion; Neckel, S., Schaffner, A., Wagner, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rozman, M.; Grinkevich, A.; Tominc, P. Occupational stress, symptoms of burnout in the workplace and work satisfaction of the age-diverse employees. Organizacija 2019, 52, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnis, M.; Pirrone, M.P.; Cuccu, S.; Agus, M.; Pedditzi, M.L.; Cortese, C.G. Burnout syndrome in reception systems for illegal immigrants in the Mediterranean. A quantitative and qualitative study of Italian practitioners. A quantitative and qualitative study of Italian practitioners. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiceno, J.M.; Alpi, S.V. Burnout: “Syndrome of burning oneself out at work (SBW)”. Acta Colomb. Psicol. 2007, 10, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Trigo, T.R.; Teng, C.T.; Hallak, J.E.C. Burnout syndrome and psychiatric disorders. Rev. Psiquiatr. Clin. 2007, 34, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinello, M.; Negrisolo, A. Quando Ogni Passione è Spenta. La Sindrome del Burnout Nelle Professioni Sanitarie; Mc Graw Hill: Milan, Italy, 2009; pp. 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Borgogni, L.; Consiglio, C.; Alessandri, G.; Schaufeli, W.B. “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater!” Interpersonal strain at work and burnout. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2012, 21, 875–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedditzi, M.L.; Nonnis, M. Psycho-social sources of stress and burnout in schools: Research on a sample of Italian teachers. Med. Lav. 2014, 105, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Edelwich, J.; Brodsky, A. Burnout: Stages of Disillusionment in the Helping Professions; Kluwer Academic Plenum Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980; pp. 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Rodríguez, F.M.; Pérez-Mármol, J.M.; Brown, T. Education burnout and engagement in occupational therapy undergraduate students and its associated factors. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacewicz, C.E.; Mellano, K.T.; Smith, A.L. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social constructs and athlete burnout. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 43, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnis, M.; Agus, M.; Pirrone, M.P.; Cuccu, S.; Pedditzi, M.L.; Cortese, C.G. Burnout and engagement dimensions in the reception system of illegal immigration in the mediterranean sea. A qualitative study on a sample of Italian practitioners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amundson, N.E.; Borgen, W.A. The dynamics of unemployment: Job loss and Job search. Pers. Guid. J. 1982, 60, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.H.; Vinokur, A.D. The JOBS program: Impact on job seeker motivation, reemployment, and mental health. In The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search; Klehe, U.-C., van Hooft, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamani, L.; Agyemang, B.C.; Afful, J.; Asumeng, M. Work attitude of Ghanaian nurses for quality health care service delivery: Application of Individual and Organizational Centered (IOC) interventions. Int. J. Res. Stud. Manag. 2018, 7, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, W.A.; Amundson, N.E. The Dynamics of Unemployment. J. Couns. Dev. 1987, 66, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnis, M.; Frau, G.; Agus, M.; Urban, A.; Cortese, C.G. Burnout without a job: An explorative study on a sample of Italian unemployed jobseekers. J. Public Health Res. 2023, 12, 227990362211492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.; Maslach, C. OCS. Organizational Checkup System. Come Prevenire il Burnout e Costruire L’impegno; Giunti OS: Firenze, Italy, 2005; pp. 68–94. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. JRN 2020, 25, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, L.; Tuzzi, A. Analyzing Written Communication in AAC Contexts: A Statistical Perspective. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2011, 27, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolasco, S. Analisi Multidimensionale dei Dati: Metodi, Strategie e Criteri D’interpretazione; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 1999; pp. 12–45. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera-Fernández, M.J.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J.; Peró-Cebollero, M. Qualitative research in psychology: Misunderstandings about textual analysis. Qual. Quant. 2011, 47, 1589–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U. Theory Building in Qualitative Research and Computer Programs for the Management of Textual Data. Soc. Res. Online 1997, 2, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasze, G.; Mattissek, A. Handbuch Diskurs und Raum: Theorien und Methoden für die Humangeographie Sowie die Sozial- und Kulturwissenschaftliche Raumforschung; Transcript Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 6–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann, G. Text Mining for Qualitative Data Analysis in the Social Sciences; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 16–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancia, F. The Logic of the T-Lab Tools Explained. 2012. Available online: http://www.tlab.it/en/toolsexplained.php (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Lancia, F. T-LAB Pathways to Thematic Analysis. 2012. Available online: http://www.tlab.it/en/tpathways.php (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Benzécri, J.-P. Correspondence Analysis Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1992; pp. 20–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lebart, L.; Piron, M.; Morineau, A. Statistique Exploratoire Multidimensionnelle: Visualisations et Interférences en Fouille de Données; Dunod: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Savaresi, S.M.; Boley, D.L. On the performance of bisecting K-means and PDDP. In Proceedings of the 2001 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM), Chicago, IL, USA, 5–7 April 2001; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, B.M.; Randel, A.E.; Collins, B.J.; Johnson, R.E. Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SAJIP 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostatistics. Impact of COVID-19 on Employment Income—Advanced Estimates. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Impact_of_COVID-19_on_employment_income_-_advanced_estimates&stable=1 (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Nemteanu, M.-S.; Dinu, V.; Dabija, D.-C. Job Insecurity, Job Instability, and Job Satisfaction in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.R.; Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.; Annabi, C.A. The impact of mindfulness practice on physician burnout: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 956651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanski, M.; Hassed, C. Mindfulness as a concept and a process. Aust. Psychol. 2008, 43, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. J. Organiz. Behav. 2017, 38, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, J.M.; Bolander, P.; Forsman, A.K. Bottom-Up Interventions Effective in Promoting Work Engagement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 730421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuori, J.; Toppinen-Tanner, S.; Mutanen, P. Effects of resource-building group intervention on career management and mental health in work organizations: Randomized controlled field trial. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 97, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, K.A.; Astin, J.; Pelletier, K.R.; Levanovich, K.; Baase, C.M.; Park, Y.Y.; Bodnar, C.M. Mindfulness goes to work impact of an online workplace intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Berkel, J.; Boot, C.R.L.; Proper, K.I.; Bongers, P.M.; Van der Beek, A.J. Effectiveness of a worksite mindfulness-based multi-component intervention on lifestyle behaviors. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

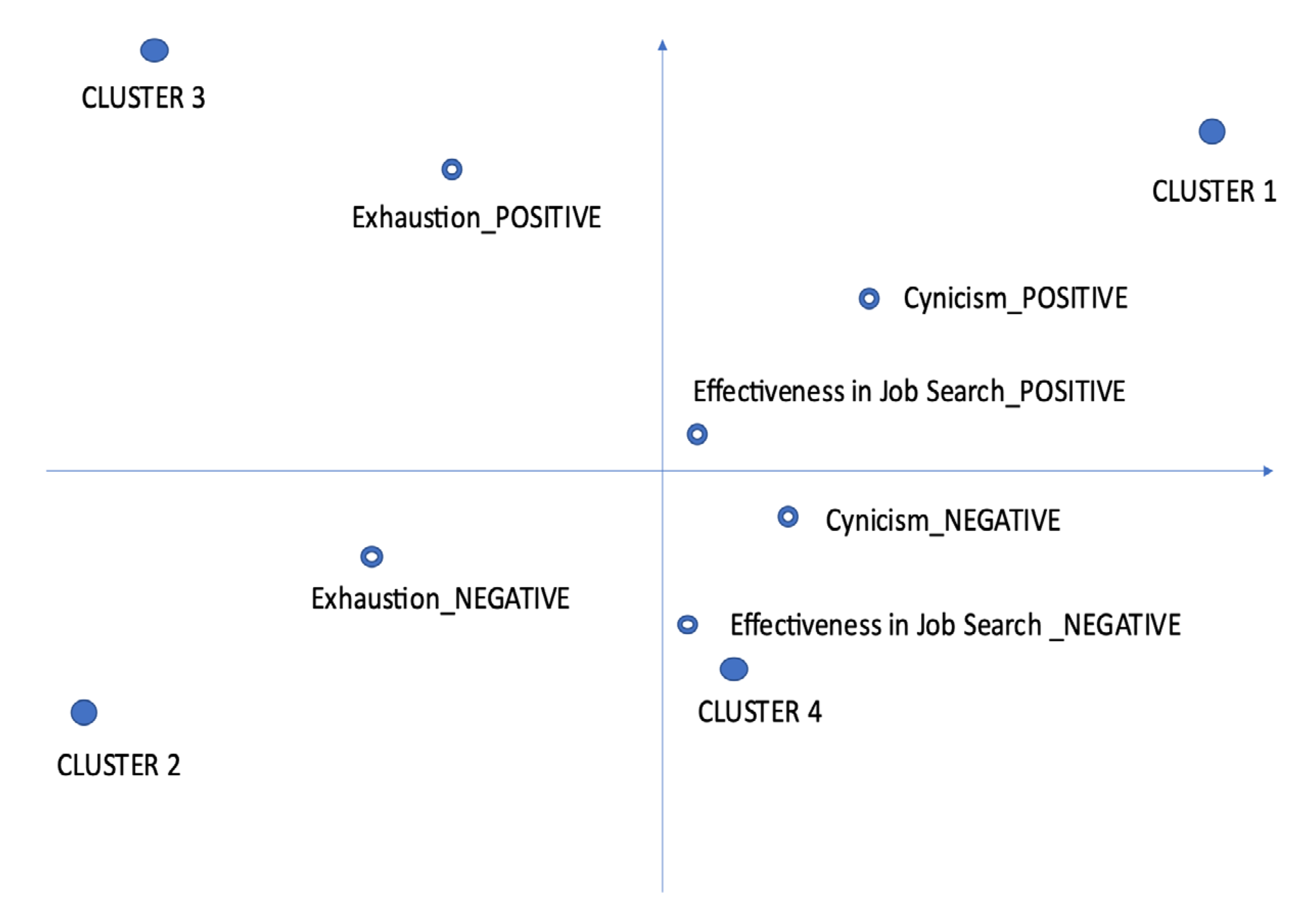

| Cluster | % of CUs in Cluster | Label | Principal Lemmas Ordered by Decreasing Frequency English (Italian) | Frequency of Lemma Occurrence | Descriptive Variables Ordered by Decreasing Chi-Squared Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21.70 | Exhaustion vs. Engagement | work (lavoro) | 178 | Cynicism Positive: chi-squared = 259.093 Effectiveness in Job Search Positive: chi-squared= 81.933 |

| pleasure (piacere) | 54 | ||||

| thinking (pensare) | 30 | ||||

| profession (professione) | 25 | ||||

| 2 | 10.83 | Disillusion vs. Hope | answering (rispondere) | 61 | Exhaustion Negative: chi-squared = 322.29 |

| CV (curriculum) | 41 | ||||

| sending (mandare) | 24 | ||||

| announcements (annunci) | 20 | ||||

| understanding (capire) | 10 | ||||

| absence (assenza) | 8 | ||||

| usual (solito) | 8 | ||||

| 3 | 12.04 | Cynicism vs. Trust | finding (trovare) | 106 | Exhaustion Positive: chi-squared = 294.003 |

| hope (speranza) | 24 | ||||

| possibility (possibilità) | 20 | ||||

| vigorous (energico) | 12 | ||||

| positive (positivo) | 11 | ||||

| 4 | 55.43 | Inefficacy vs. Efficacy | searching (cercare) | 76 | Effectiveness in Job Search Negative: chi-squared = 88.319 Cynicism Negative: chi-squared = 8.617 |

| experience (esperienza) | 52 | ||||

| succeeding (riuscire) | 48 | ||||

| working (lavorare) | 44 | ||||

| seek (ricerca) | 36 | ||||

| putting (mettere) | 31 | ||||

| asking (chiedere) | 27 | ||||

| arriving (arrivare) | 26 | ||||

| taking (prendere) | 25 | ||||

| ability (capacità) | 20 | ||||

| difficulty (difficoltà) | 19 | ||||

| situation (situazione) | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nonnis, M.; Agus, M.; Frau, G.; Urban, A.; Cortese, C.G. Job Seekers’ Burnout and Engagement: A Qualitative Study of Long-Term Unemployment in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115968

Nonnis M, Agus M, Frau G, Urban A, Cortese CG. Job Seekers’ Burnout and Engagement: A Qualitative Study of Long-Term Unemployment in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115968

Chicago/Turabian StyleNonnis, Marcello, Mirian Agus, Gianmarco Frau, Antonio Urban, and Claudio Giovanni Cortese. 2023. "Job Seekers’ Burnout and Engagement: A Qualitative Study of Long-Term Unemployment in Italy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115968

APA StyleNonnis, M., Agus, M., Frau, G., Urban, A., & Cortese, C. G. (2023). Job Seekers’ Burnout and Engagement: A Qualitative Study of Long-Term Unemployment in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115968