COVID-19 and Masking Disparities: Qualitative Analysis of Trust on the CDC’s Facebook Page

Abstract

:1. Introduction

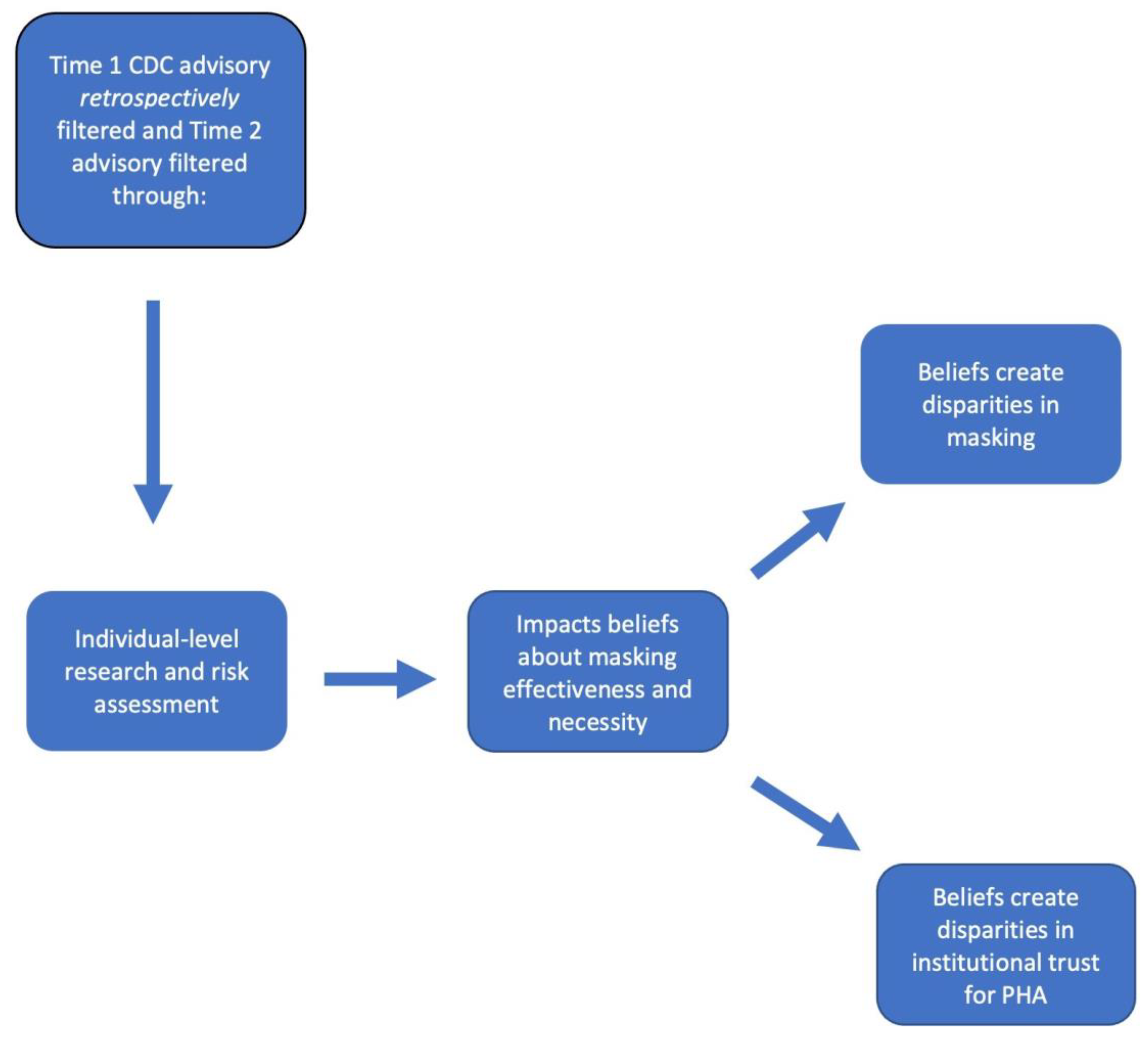

1.1. Theory

1.2. Summary and Grounded Theory Outcomes

1.3. Research Objectives and Questions

2. Related Works

2.1. Institutional Trust and Rapid Change

2.2. COVID-19, Masking, and SM

2.3. Current Methodology Used in SM Analysis of Masking

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Methods and Data Source

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Theme 1—Dispute over Effectiveness of DIY Masking

…there’s no scientific evidence of the usefulness of universal masks, otherwise CDC would have issued a recommendation about it… Globally, scientific evidence about masks (surgical or N95 not to mention “cloth” masks) is sparse and makes it really hard for both the people and health organizations.(User SLB)

The government didn’t want civilians buying up [N95] masks, adding to the shortage, needed by healthcare workers. So they were willing to sacrifice the general public. Also, the government is allowing the people to think BANDANAS work! They don’t! The virus is microscopic and goes right through regular fabric. I was a surgical nurse.(User FPG)

4.2. Theme 2—Conflicting Mask Advisories

I hope everyone clearly understands that wearing masks is not to protect you from the virus but to protect others from you. Since you may have the virus without knowing it and if you cough and sneeze without covering yourself you will infect others without knowing it. So please wear masks everyone…(User RFH)

They knew [face masks work]. If not, they SHOULD HAVE. Why did they not see China wearing masks???? Why did they not realize that all viruses are nonsymptomatic [sic] for days before symptoms appear???? All doctors and nurses and most people know this. Not waited til [sic] it was proven. IT was just common sense. CDC are murderers. No Excuses!(User RFJ)

How many people died before the CDC states the obvious. Started with: They don’t work. They work, but only for medical personnel, they work but only by stopping you from spreading it… you wouldn’t be able to wear one properly, they work but would make you overconfident. Did I miss any? Wear a fecking [sic] mask it’s obvious.(User FSK)

We can no longer trust the CDC… they are on Trump’s payroll. Cloth masks are NOT safe enough!!! Why is the richest and most powerful country in the world telling us how to do DIY life saving measures instead of providing n95 masks for all??(User EAL)

4.3. Theme 3—CDC Waited Too Long

…just shows how everyone has duty to form [sic] own opinions and look out for themselves. I could not believe the things that were being said by “officials” when I have watched this unfold for months and new [sic] it was all fluff. It’s been airborne, it’s deadly, it leaves you with impaired lung function. Is it going to wipe out the entire world—no but a lot of people are at risk and warning public in January and taking steps would have made this a lot less deadly.(User EVP)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: Stop the Spread of Germs 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/cdc/posts/pfbid02WnY8NnQgA3mqYsgvKorZbGSWDAc8N291YXX9V1iRueFtsH8YQDGVjLdd2tgfuFnJl?__cft__[0]=AZW4oNcre1cENJSydA2njDFw-7csuQFsWvCu-FtBmA9tIcxPYluzVnRldT-QdWIrM3kblA7-oUwQjGswbFUuuufUfT7X0FqN32U3r6rI2kCzlV_R9JoYwHcevoEg1HeRtjPb4G3J-xPYVBpInz48EZ3F&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control Facebook Page. Wondering if a Mask Would Protect You from COVID-19? 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/cdc/posts/pfbid02f4JBbsKWeEvZe1c6V1Gsvs1jDixoH9qRpwonebiY4QtaJGVaXs9K4FnNqB91cAm3l?__cft__[0]=AZWtQDpU3TRZ9RTLJrbXWOi98FW5DhWq8Uskn3vssi5Eh_t3VEgPvRH2NGGcIJrcpVwGLFBS-lk3i80XNb7v9dR_N2knM_cpoGlnaIB32ak2QhdrBzTxiC_xSYgwGTTLxc-DYG_nCjemFllecZwyR2vo&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Aguirre-Duarte, N. Can People with Asymptomatic or Pre-Symptomatic COVID-19 Infect Others: A Systematic Review of Primary Data. Public Glob. Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s Recommendation Use of Cloth Face Coverings. 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/cdc/posts/pfbid02nQu9YMpKs2VCGykarMGWiybxA48m1s61jWVLUjZaZ3tB1m1kAcp19axGBYD1Qjg1l?comment_id=10157784741681026&reply_comment_id=10157784769721026 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Beck, U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, D. Risk, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Risk, Trust, Reflexivity. In Reflexive Modernization; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 184–197. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Blendon, R.J.; Benson, J.M.; Hero, J.O. Public Trust in Physicians—U.S. Medicine in International Perspective. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1570–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Laurent-Simpson, A.; Lo, C.C. Risk society online: Zika virus, social media and distrust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sociol. Health Illn. 2019, 41, 1270–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.C.; Laurent-Simpson, A. How SES May Figure in Perceptions of Zika Risks and in Preventive Action. Sociol. Spectr. 2018, 38, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney Rutten, L.J.; Blake, K.D.; Greenberg-Worisek, A.J.; Allen, S.V.; Moser, R.P.; Hesse, B.W. Online Health Information Seeking among US Adults: Measuring Progress toward a Healthy People 2020 Objective. Public Health Rep. 2019, 134, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontos, E.Z.; Emmons, K.M.; Puleo, E.; Viswanath, K. Communication Inequalities and Public Health Implications of Adult Social Networking Site Use in the United States. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 3), 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heldman, A.B.; Schindelar, J.; Weaver, J.B. Social Media Engagement and Public Health Communication: Implications for Public Health Organizations Being Truly “Social”. Public Health Rev. 2013, 35, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, B.F.; Fraustino, J.D.; Jin, Y. How Disaster Information Form, Source, Type, and Prior Disaster Exposure Affect Public Outcomes: Jumping on the Social Media Bandwagon? J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2015, 43, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L. COVID-19 information on social media and preventive behaviors: Managing the pandemic through personal responsibility. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loon, J.V. Understanding epidemics in apocalypse culture. In Risk and Technological Culture; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Washer, P. Lay perceptions of emerging infectious diseases: A commentary. Public Underst. Sci. 2011, 20, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, J.A.; Hinote, B.P. Chronic illness as incalculable risk: Scientific uncertainty and social transformations in medicine. Soc. Theory Health 2011, 9, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, S.; Shriver, T.E.; Mix, T.L. Risk Society and Contested Illness: The Case of Nuclear Weapons Workers. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 73, 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, J.O. Health and illness as drivers of risk language in the news media—A case study of The Times. Health Risk Soc. 2020, 22, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhalovskiy, E.; French, M. COVID-19, public health, and the politics of prevention. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 42, e4–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordani, R.C.F.; Giolo, S.R.; Zanoni Da Silva, M.; Muhl, C. Risk perception of COVID-19: Susceptibility and severity perceived by the Brazilian population. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Florin, M.-V.; Renn, O. COVID-19 risk governance: Drivers, responses and lessons to be learned. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.P.; Hanna, E.; McCartney, M.; Dingwall, R. Science, society, and policy in the face of uncertainty: Reflections on the debate around face coverings for the public during COVID-19. Crit. Public Health 2020, 30, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesser-Edelsburg, A.; Mordini, E.; James, J.J.; Greco, D.; Green, M.S. Risk Communication Recommendations and Implementation during Emerging Infectious Diseases: A Case Study of the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2014, 8, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Duong, H.T.; Nguyen, H.T. Media exposure and intentions to wear face masks in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak: The mediating role of negative emotions and risk perception. Atl. J. Commun. 2021, 30, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L. The Intentions to Wear Face Masks and the Differences in Preventive Behaviors between Urban and Rural Areas during COVID-19: An Analysis Based on the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Akhtar, N.; Ahmad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Wu, H.; Yang, C. Assessing Public Willingness to Wear Face Masks during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Fresh Insights from the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, R.W.; Foerster, T.A. Predicting intentions to practice COVID-19 preventative behaviors in the United States: A test of the risk perception attitude framework and the theory of normative social behavior. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 2744–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokemper, S.E.; Cucciniello, M.; Rotesi, T.; Pin, P.; Malik, A.A.; Willebrand, K.; Paintsil, E.E.; Omer, S.B.; Huber, G.A.; Melegaro, A. Experimental evidence that changing beliefs about mask efficacy and social norms increase mask wearing for COVID-19 risk reduction: Results from the United States and Italy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palcu, J.; Schreier, M.; Janiszewski, C. Facial mask personalization encourages facial mask wearing in times of COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Alhuwail, D.; Househ, M.; Hamdi, M.; Shah, Z. Top Concerns of Tweeters during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Infoveillance Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obiała, J.; Obiała, K.; Mańczak, M.; Owoc, J.; Olszewski, R. COVID-19 misinformation: Accuracy of articles about coronavirus prevention mostly shared on social media. Health Policy Technol. 2021, 10, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Lopez Segui, F.; Moreno-Sánchez, P.A. A Social Network Analysis of Tweets Related to Masks during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourali, M.; Drake, C. The Challenge of Debunking Health Misinformation in Dynamic Social Media Conversations: Online Randomized Study of Public Masking During COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e34831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, A.; Nielsen, A.; Bellows, Z.; Farrell, E.; Durette, P.-N.; Banda, J.M.; Cupchik, G. Changes in Public Response Associated with Various COVID-19 Restrictions in Ontario, Canada: Observational Infoveillance Study Using Social Media Time Series Data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, F.; Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Fazea, Y. The Impact of Social Media Shared Health Content on Protective Behavior against COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskhodchikov, A.N.; Pilgun, M. COVID-19 and Public Health: Analysis of Opinions in Social Media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Shen, Z.; Shah, N.; Cuomo, R.; Cai, M.; Brown, M.; Li, J.; Mackey, T. Characterizing Weibo Social Media Posts from Wuhan, China during the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Content Analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e24125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoernke, K.; Djellouli, N.; Andrews, L.; Lewis-Jackson, S.; Manby, L.; Martin, S.; Vanderslott, S.; Vindrola-Padros, C. Frontline healthcare workers’ experiences with personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: A rapid qualitative appraisal. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhasin, T.; Butcher, C.; Gordon, E.; Hallward, M.; LeFebvre, R. Does Karen wear a mask? The gendering of COVID-19 masking rhetoric. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglietto, F.; Rossi, L.; Bennato, D. The Open Laboratory: Limits and Possibilities of Using Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube as a Research Data Source. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2012, 30, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, G.A.; Elsbach, K.D. Ethnography and Experiment in Social Psychological Theory Building: Tactics for Integrating Qualitative Field Data with Quantitative Lab Data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 36, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, K.A.; Barile, J.P.; Guerin, R.J.; Vanden Esschert, K.L.; Jeffers, A.; Tian, L.H.; Garcia-Williams, A.; Gurbaxani, B.; Thompson, W.W.; Prue, C.E. Factors Associated with Cloth Face Covering Use among Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, K.M.C.; Keating, J.A.; Safdar, N. Crisis Communication and Public Perception of COVID-19 Risk in the Era of Social Media. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Wu, Q.; Hao, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Alias, H.; Shen, M.; Hu, J.; Duan, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. The role of institutional trust in preventive practices and treatment-seeking intention during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak among residents in Hubei, China. Int. Health 2022, 14, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H.; Washer, P.; Solberg, C. Public engagement with emerging infectious disease: The case of MRSA in Britain. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; 4. Paperback Printing; Aldine: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottfried, J.; Shearer, E. News Use across Social Medial Platforms 2016; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gramlich, J. 10 Facts about Americans and Facebook; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/01/facts-about-americans-and-facebook/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Walker, M.; Matsa, K.E. News Consumption across Social Media in 2021; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/09/20/news-consumption-across-social-media-in-2021/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- U.S. Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health—Appendix A, Summary of the Public Health System in the United States; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218212 (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Lofland, J. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis; Wadsworth/Thomson Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, P. The role of fear in modern societies. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e52157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupton, D.; Southerton, C.; Clark, M.; Watson, A. The Face Mask in COVID Times: A Sociomaterial Analysis; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.W. Trust in Health Care in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 2373–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKay, M.; Cimino, A.; Yousefinaghani, S.; McWhirter, J.E.; Dara, R.; Papadopoulos, A. Canadian COVID-19 Crisis Communication on Twitter: Mixed Methods Research Examining Tweets from Government, Politicians, and Public Health for Crisis Communication Guiding Principles and Tweet Engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, P. The Shifting Engines of Medicalization. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, P.; Leiter, V. Medicalization, markets and consumers. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 158–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, P.C.-I.; Jiang, W.; Pu, G.; Chan, K.-S.; Lau, Y. Social Media Engagement in Two Governmental Schemes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Macao. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, M.; Ellison, N.B.; Lampe, C.; Lenhart, A.; Madden, M. Social Media Update 2014. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2015. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/social-media-update-2014 (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Gauchat, G. Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 77, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jamison, A.M.; Quinn, S.C.; Freimuth, V.S. “You don’t trust a government vaccine”: Narratives of institutional trust and influenza vaccination among African American and white adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 221, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mierlo, T. The 1% Rule in Four Digital Health Social Networks: An Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Major Themes | Sample Data Points (by Theme and Trust) | N of Posts |

|---|---|---|

| Disparities in Masking and Institutional Trust: | ||

| Dispute Over Effectiveness of DIY Masking (do not trust CDC now, no masking from the start) | “Make sure your [sic] not wearing a mask. They don’t protect you.”—User KNZ (Indirect distrust) “If COVID can in fact go right through material, then why on earth would anyone settle for a material ‘mask?’”—User PMY (Indirect distrust) “They need to address this. It’s ridiculous that the CDC does not understand micron sizes of fabric and the size of COVID19. They have to know. It [second advisory] has to be about alleviating fear.”—User TKX (Direct distrust) “Making masks[s] will not work […] just stay home now that works.” User MKW (Indirect distrust) “Unfortunately homemade masks and clothes likes scarfs [sic] don’t protect from particles going through…”—User AAV (Indirect distrust) | N = 124 |

| Conflicting Mask Advisories (do not trust CDC—either already masking anyway or will now) | “CDC was irresponsible in telling the general public not to wear masks for the sole reason that they didn’t have any [masks]. They should have told people from the beginning to fashion a mask. Instead they shamed people into not wearing them even if they already had one they could have used.”—User CIU (Direct distrust) “Really CDC [sic], you are supposed to be the smartest people, hospitals follow your guidelines… Before airborne, now droplet. Before no mask now wear mask guidelines. No n95 when in fact that’s the best for now to protect the HC [healthcare] workers.”—User KGT (Indirect distrust) “The U.S. government knew all of this for months. They didn’t prepare and when they realized they were screwed because of inaction they tried to tell us not to wear masks to save them for the medical field. It NEVER made sense not to wear a mask.” User TCS (Direct distrust) | N = 74 |

| Disappointment in CDC for Length of Time to Pro-Masking Advisory (do not trust CDC—either already masking anyway or will mask now) | “People could have been fashioning masks 2 months ago.”—User NDN (Indirect distrust) “They [CDC] have had this thing in a lab since Dec. Nothing new is coming out. They already know EVERYTHING about this virus. Trust me when I tell you, by the time they tell you to wear a mask, they already know it’s way worse than even they are telling you now.”—TCS (Direct distrust) “I’ve been sewing them [DIY masks] like crazy for my family members. I happily would have started sewing them in January if the CDC had been more honest with the public about the necessity of wearing them.”—User SCM (Direct distrust) | N = 55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laurent-Simpson, A. COVID-19 and Masking Disparities: Qualitative Analysis of Trust on the CDC’s Facebook Page. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126062

Laurent-Simpson A. COVID-19 and Masking Disparities: Qualitative Analysis of Trust on the CDC’s Facebook Page. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126062

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaurent-Simpson, Andrea. 2023. "COVID-19 and Masking Disparities: Qualitative Analysis of Trust on the CDC’s Facebook Page" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126062

APA StyleLaurent-Simpson, A. (2023). COVID-19 and Masking Disparities: Qualitative Analysis of Trust on the CDC’s Facebook Page. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126062