Diagnostic Accuracy and Measurement Properties of Instruments Screening for Psychological Distress in Healthcare Workers—A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Assessment of the Methodological Quality of the Studies

2.6. Rating of the Measurement Properties

2.7. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

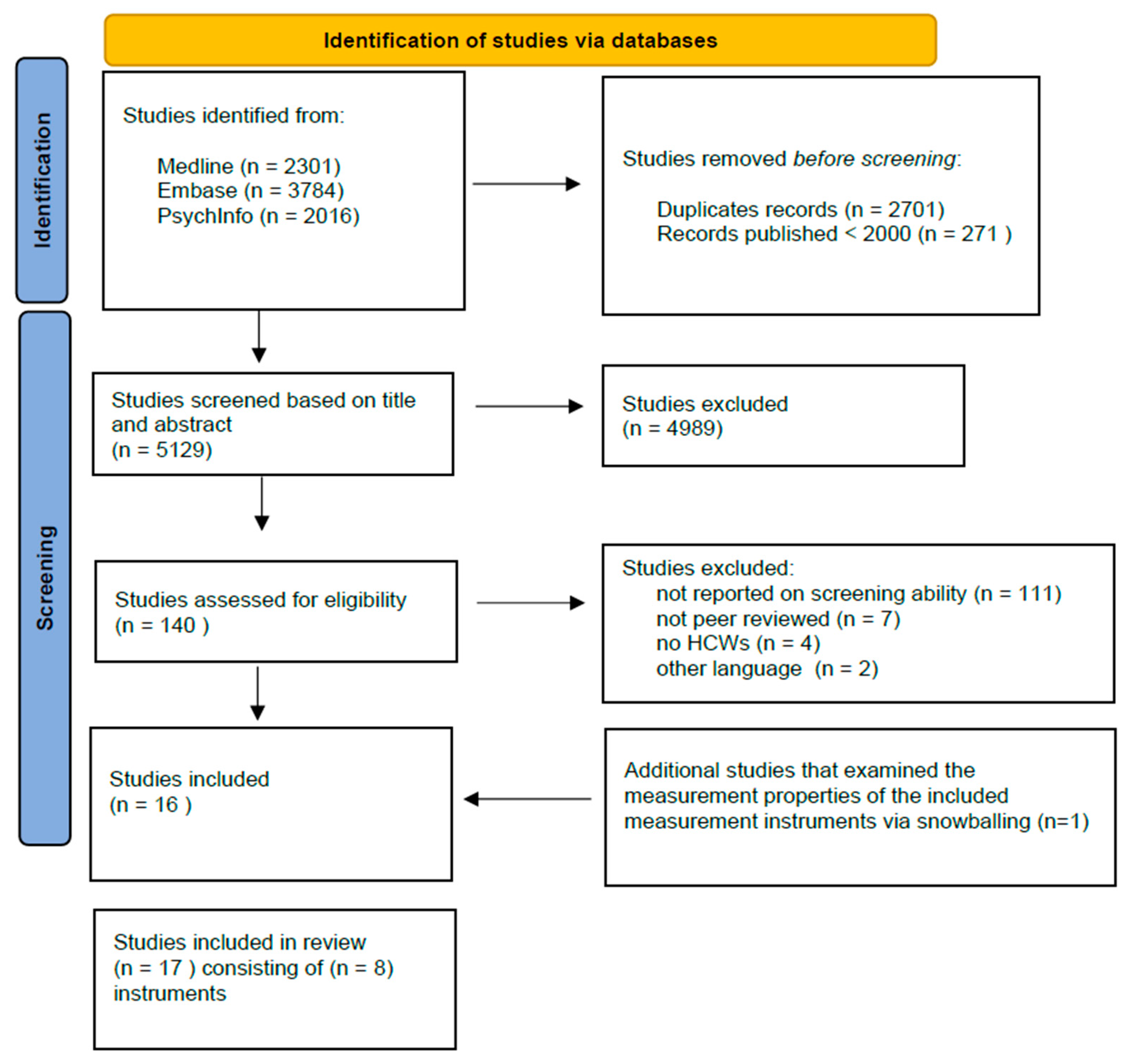

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Assessment of the Methodological Quality of the Studies

3.4. Rating of the Measurement Properties

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Interpretation of Results

4.2. Comparison to Other Literature

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Implications of Results for Practice, Policy and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slater, P.J.; Edwards, R.M.; Badat, A.A. Evaluation of a staff well-being program in a pediatric oncology, hematology, and palliative care services group. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2018, 10, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridner, S.H. Psychological distress: Concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 45, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Molen, H.F.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; de Groene, G. Work-related psychosocial risk factors for stress-related mental disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Loerbroks, A.; Angerer, P.; Siegrist, J. Work stress and the risk of recurrent coronary heart disease events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2015, 28, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, T.W.; Smith, F.; Goldacre, M.J. Why doctors consider leaving UK medicine: Qualitative analysis of comments from questionnaire surveys three years after graduation. J. R. Soc. Med. 2018, 111, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutekom, M.; Vansenne, F.; McCaffery, K.; Essink-Bot, M.-L.; Stronks, K.; Bossuyt, P.M.M. The effects of screening on health behaviour: A summary of the results of randomized controlled trials. J. Public Health 2010, 33, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, N.; Lesage, A.; Wang, J. Should psychological distress screening in the community account for self-perceived health status? Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, F.R.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Ketelaar, S.M.; van Dijk, F.J.; Sluiter, J.K. The Mental Vitality @ Work Study: Effectiveness of a mental module for workers’ health surveillance for nurses and allied health care professionals on their help-seeking behavior. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaar, S.M.; Gartner, F.R.; Bolier, L.; Smeets, O.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Sluiter, J.K. Mental Vitality @ Work-A workers′ health surveillance mental module for nurses and allied health care professionals: Process evaluation of a randomized controlled trial. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxim, L.D.; Niebo, R.; Utell, M.J. Screening tests: A review with examples. Inhal. Toxicol. 2014, 26, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoffen, M.F.; Twisk, J.W.; Heymans, M.W.; de Bruin, J.; Joling, C.I.; Roelen, C.A. Psychological distress screener for risk of future mental sickness absence in non-sicklisted employees. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; The QUADAS-Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenderink, A.F.; Zoer, I.; van der Molen, H.F.; Spreeuwers, D.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; van Dijk, F.J. Review on the validity of self-report to assess work-related diseases. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2012, 85, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.M.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.W.M.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.Y.; Hemsworth, D.; Lim, S.H.; Ayre, T.C.; Ang, E.; Lopez, V. Evaluation of Psychometric Properties of Professional Quality of Life Scale Among Nurses in Singapore. J. Nurs. Meas. 2020, 28, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boezeman, E.J.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Sluiter, J.K. Predictive value and construct validity of the work functioning screener-healthcare (WFS-H). J. Occup. Health 2016, 58, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.-T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, B.-Y.; Yi, T.-W.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Zheng, B.; Luo, D.; Du, P.-X.; Jiang, Y. A multicenter study on the validation of the burnout battery: A new visual analog scale to screen job burnout in oncology professionals. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, E.D.; Mohr, D.; Lempa, M.; Joos, S.; Fihn, S.D.; Nelson, K.M.; Helfrich, C.D. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometric evaluation. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Johnson, P.O.; Johnson, L.M.; Halasy, M.P.; Gossard, A.A.; Satele, D.; Shanafelt, T. Efficacy of the Well-Being Index to identify distress and stratify well-being in nurse practitioners and physician assistants. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2019, 31, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Satele, D.; Shanafelt, T. Ability of a 9-Item Well-Being Index to Identify Distress and Stratify Quality of Life in US Workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Utility of a brief screening tool to identify physicians in distress. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Ability of the physician well-being index to identify residents in distress. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2014, 6, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadare, O.O.; Doucette, W.R.; Gaither, C.A.; Schommer, J.C.; Arya, V.; Bakken, B.; Kreling, D.H.; Mott, D.A.; Witry, M.J. Use of the Professional Fulfillment Index in Pharmacists: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiana, L.; Arena, F.; Oliver, A.; Sanso, N.; Benito, E. Compassion Satisfaction, Compassion Fatigue, and Burnout in Spain and Brazil: ProQOL Validation and Cross-cultural Diagnosis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, R.; Musick, D.; Greenawald, M.; Carter, K.; Bogue, R.; Penwell-Waines, L. Evaluating the Burnout-Thriving Index in a Multidisciplinary Cohort at a Large Academic Medical Center. South. Med. J. 2019, 112, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, V.; Girgis, A. Can a single question effectively screen for burnout in Australian cancer care workers? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, D.; Baregheh, A.; Aoun, S.; Kazanjian, A. A critical enquiry into the psychometric properties of the professional quality of life scale (ProQol-5) instrument. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 39, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohland, B.M.; Kruse, G.R.; Rohrer, J.E. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health 2004, 20, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, T.; Iecovich, E.; Shvartzman, P. Psychometric Characteristics of the Hebrew Version of the Professional Quality-of-Life Scale. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 52, 575–581.e571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trockel, M.; Bohman, B.; Lesure, E.; Hamidi, M.S.; Welle, D.; Roberts, L.; Shanafelt, T. A Brief Instrument to Assess Both Burnout and Professional Fulfillment in Physicians: Reliability and Validity, Including Correlation with Self-Reported Medical Errors, in a Sample of Resident and Practicing Physicians. Acad. Psychiatry 2018, 42, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddimba, A.C.; Scribani, M.; Nieves, M.A.; Krupa, N.; May, J.J.; Jenkins, P. Validation of Single-Item Screening Measures for Provider Burnout in a Rural Health Care Network. Eval. Health Prof. 2016, 39, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeflang, M.M.G.; Moons, K.G.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Zwinderman, A.H. Bias in Sensitivity and Specificity Caused by Data-Driven Selection of Optimal Cutoff Values: Mechanisms, Magnitude, and Solutions. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veldhoven, M.; Broersen, S. Measurement quality and validity of the ‘need for recovery scale’. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, i3–i9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeflang, M.M.; Deeks, J.J.; Gatsonis, C.; Bossuyt, P.M. Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimundić, A.M. Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy: Basic Definitions. Ejifcc 2009, 19, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.M.; Lijmer, J.G.; Moher, D.; Rennie, D.; de Vet, H.C. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD initiative. Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Population | Instrument Administration | Reference Standard | Measurement Properties Examined | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Author/Year | Construct | Sample Size | Occupation | Mean Age (SD) | Female n (%) | Mode of Administration | Language | Setting | Response Rate | ||

| WFS-H | Boezeman et al., 2016 [17] | Unimpaired work functioning | 249 | Nurses | 47 (12) | 209 (84%) | Self-administration | Dutch | Academic Medical Center | 24% | NWFQ, EWPS, 4DSQ | Criterion validity |

| Burnout battery | Deng et al., 2017 [18] | Burnout syndrome | 538 | Physicians, nurses | nr | 430 (80%) | Self-administration | nr | University, cancer and municipal hospitals | 81% | MBI-HSS, Doctors’ Job Burnout Questionnaire. | Criterion validity |

| Physicians well-being Index | Dyrbye et al., 2013 [22] | Multi-dimensions of distress | 7288 | Physicians | nr | 1530 (21%) | Self-administration | English | nr | 26% | MBI-personal accomplishment | Criterion validity |

| Dyrbye et al., 2014 [23] | Multi-dimensions of distress | 1701 | Residents | nr | 918 (54%) | Self-administration | English | nr | 23% | Mental QOL and level of fatigue on a standardized linear analogue scale. | Criterion validity | |

| Dyrbye et al., 2019 [20] | Multi-dimensions of distress | 976 | Nurses | 52 (11) | 892 (92%) | Self-administration | English | nr | 47% | Overall QOL on a standardized linear analogue scale. MBI-depersonalization MBI- emotional exhaustion | Criterion validity | |

| 60 | Physician assistants | 46 (11) | 409 (69%) | 30% | ||||||||

| 9-item well-being index | Dyrbye et al., 2016 [21] | Multi-dimensions of distress | 5392 | General working population, physicians | nr | 2458 (46%) | Self-administration | English | nr | nr | Overall QOL on a standardized linear analogue scale. MBI-depersonalization MBI-emotional exhaustion | Criterion validity |

| Professional quality of Life Scale | Ang et al., 2020 [16] | Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue | 1338 | Nurses | nr | 1250 (93%) | Self-administration | nr | Academic medical hospital | 28% | PANAS | Internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypotheses testing |

| Galiana et al., 2017 [25] | Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue | 385 | Physicians, nurses, Psychologists, nursing assistants, social workers, other | nr | 300 (78%) | Self-administration | Spanish | nr | nr | na | Internal consistency, structural validity. | |

| Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue | 161 | Physicians, nurses, psychologists, nursing assistants, social workers, other | nr | 143 (89%) | Self-administration | Portuguese | nr | nr | na | Internal consistency, structural validity. | ||

| Hemsworth et al., 2018 [28] | Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue | 273 | Australian nurses | 40 (nr) | 253 (93%) | Self-administration | English | Hospital | 21% | na | Internal consistency, structural validity, hypothesis testing. | |

| 303 | Canadian nurses | 40 (nr) | 263 (87%) | 30% | ||||||||

| 651 | Canadian palliative care workers | 53 (nr) | 553 (85%) | 67% | ||||||||

| Samson et al., 2016 [30] | Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue | 377 | Physicians | 48 (10) | 20% | Self-administration | Hebrew | Primary health and palliative care setting | 35% | Shirom-Melamed burnout measurement | Internal consistency, structural validity, hypothesis testing, criterion validity | |

| Nurses | 80% | |||||||||||

| Social workers | nr | |||||||||||

| Burnout-thriving index | Gates et al., 2019 [26] | Burnout | 1365 | Physicians, fellows, residents, medical students, nurses | 41 (nr) | 979 (72%) | Self-administration | English | Hospital | 45% | MBI | Criterion validity |

| Single item burnout | Dolan et al., 2015 [19] | Burnout | 5404 | Physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical associates administrative clerks. | nr (nr) | nr (nr) | Self-administration | English | Primary care clinic | 25% | MBI- emotional exhaustion | Criterion validity |

| Hansen et al., 2010 [27] | Burnout | 740 | Nurse oncologist, palliative care physician, other health professionals, research and administration | 46 (10) | 499 (78%) | Self-administration | English | Various medical institutions | 56% | MBI-HSS emotional exhaustion, single-item self-defined burnout scale | Criterion validity | |

| Rohland et al., 2004 [29] | Burnout | 307 | Physicians | 44 (nr) | 78 (26%) | Self-administration | English | Alumni of the Texas Tech University school of medicine | 43% | MBI | Criterion validity | |

| Waddimba et al., 2016 [32] | Burnout | 308 | Rural physician/non-physician practitioners | 49 (nr) | 141 (46%) | Self-administration | English | Academic medical centre, community hospitals, clinics and school-based health centres | 65% | MBI-HSS emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, The Single-item Burnout, measure from the Physician Work Life Study | Criterion validity | |

| Professional fulfillment index | Trockel et al., 2018 [31] | Professional wellbeing | 250 | Physicians | nr | 123 (49%) | Self-administration | English | Academic medical centre | nr | MBI-HSS the one-item self-defined burnout measure, sleep-Related Impairment Depression, and Anxiety scales, WHOQOL-BREF | Internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypothesis testing, criterion validity. |

| Fadare et al., 2021 [24] | Professional wellbeing | 4716 | Pharmacists | 44(13) | 3059(65%) | Self-administration | English | nr | 56% | nr | Internal consistency, Structural validity | |

| Instrument/Author/Year | Domains | Applicability Concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (Worker) Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | Flow and Timing | Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | |

| WFS-H/Boezeman et al., 2016 [17] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Burnout Battery/Deng et al., 2017 [18] | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Physician well-being index/Dyrbye et al., 2013 [22] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Physician well-being index/Dyrbye et al., 2014 [23] | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| 9 item physician well-being index/Dyrbye et al., 2016 [21] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Physician well-being index/Dyrbye et al., 2019 [20] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Professional quality of life/Samson et al., 2016 [30] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Burnout-thriving index/Gates et al., 2011 [26] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Single Item of BO/Dolan et al., 2015 [19] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Single Item of BO/Hansen et al., 2010 [27] | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Single Item of BO/Rohland et al., 2004 [29] | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Single Item of BO/Waddimba et al., 2016 [32] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| PFI/Trockel et al., 2018 [31] | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Hypotheses Testing | Criterion Validity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument (Ref) | Sub-Samples | Subscales | Methodological Quality of the Studies | Results Measurement Property (Rating) A. Hypotheses Confirmed 75% | Methodological Quality of the Studies | Results Measurement Property (Rating) A. Area under the Curve B. Pearson Correlations C. Spearman Correlations D. Sensitivity | Cut-Off-Point | Correlation with Scale | Comparator Measurement Instrument |

| WHF-S Boezeman et al., 2016 [17] | na | Cognitive aspects of task execution and general incident | Very good | A. WFS-H correlates moderately with productivity general health and distress (+) | Unclear | A. 0.79 (+) D. 71% (+) | 0.25 | na | na |

| Avoidance behavior | A. 0.71 (+) D. 56% (−) | 0.13 | |||||||

| Conflicts and irritations with colleagues | A. 0.71 (+) D. 56% (−) | 0.29 | |||||||

| Impaired contact with patients and family | A. 0.64 (−) D. 42% (−) | 0.19 | |||||||

| Lack of energy and motivation | A. 0.82 (+) D. 76% (+) | 0.32 | |||||||

| Burnout Battery Deng et al., 2017 [18] | na | na | na | na | Unclear | A. 0.76 (+) D. 68% (−) | 3 bars | na | na |

| A. 0.71 (+) D. 67% (−) | 3 bars | ||||||||

| A. 0.62 (−) D.55% (−) | 3 bars | ||||||||

| Physician well-being index Dyrbye et al., 2013 [22] | na | Low quality of life | na | na | Unclear | A. 0.85 (+) | ≥1/2 standard deviation | na | Standardized linear analogue scale MBI-PA |

| High fatigue | A. 0.78 (+) | ≥1/2 standard deviation | |||||||

| Suicidal ideation | A. 0.80 (+) | ≥1/2 standard deviation | |||||||

| Physician well-being index Dyrbye et al., 2014 [23] | na | Low mental quality | na | na | Unclear | D. 70% (+) | ≥5 | na | Standardized linear analogue scale |

| High fatigue | D. nr | nr | nr | ||||||

| Suicidal ideation | D. nr | nr | nr | ||||||

| 9 item well-being indexDyrbye et al., 2016 [21] | Physician sample | High quality of life | na | na | Unclear | A. 0.80 (+) | ≥1/2 standard deviation | na | Standardized linear analogue scale |

| Low quality of life | A. 0.84 (+) | ≥1/2 standard deviation | Standardized linear analogue scale | ||||||

| Fatigue | A. 0.74 (+) | ≥1/2 standard deviation | 10-point linear analogue scale | ||||||

| Burnout | A. 0.85 (+) | nr | MBI | ||||||

| Physician well-being Index Dyrbye et al., 2019 [20] | na | Quality of life | na | na | Unclear | A. 0.81 (+) | ≥0.5 standard deviation | na | Linear analogue scale |

| Fatigue | A. 0.62 (−) | ≥0.5 standard deviation | Linear analogue scale | ||||||

| Suicidal ideation | A. 0.65 (−) | Reported suicidal ideation within the past 12 months | Single item suicidal ideation | ||||||

| Burnout | A. 0.77 (+) | EE ≥ 0.27 and DP ≥ 0.28 | MBI | ||||||

| Professional quality of life scale Ang et al., 2020 [16] | na | na | Inadequate | ? | na | na | na | na | na |

| Professional quality of life scale Hemsworth et al., 2018 [28] | Australian | Compassion satisfaction | Inadequate | ? | na | na | na | na | na |

| Burnout | |||||||||

| Secondary traumatic stress | |||||||||

| Canadian | Compassion satisfaction | Inadequate | ? | ||||||

| Burnout | |||||||||

| Secondary traumatic stress | |||||||||

| Professional quality of life scale Samson et al., 2016 [30] | na | Compassion satisfaction | Inadequate | ? | Unclear | B. 0.72 (+) | na | na | UWES-9 |

| Burnout | B. 0.57 (−) | SMBM | |||||||

| Secondary traumatic stress | B. 0.40 (−) | PDEQ | |||||||

| Professional fulfilment Trockel et al., 2018 [31] | na | Professional fulfilment | Inadequate | ? | Unclear | A. 0.81 (+) D. 73% (+) | 3.0 | na | na |

| Burnout | A. 0.85 (+) D. 72% (+) | 3.0 | |||||||

| Single Item burnout Waddimba et al., 2016 [32] | na | na | na | na | Unclear | C. 0.72 (+) | na | Physicians work life with EE | MBI |

| C. 0.41 (−) | Physicians work life with DP | ||||||||

| C. 0.89 (+) | I feel burned out from work with EE | ||||||||

| C. 0.81 (+) | I have become more callous with DP | ||||||||

| Single Item burnout Hansen et al., 2010 [27] | na | na | na | na | Unclear | B. 0.68 (−) | na | EE and self-defined burnout | MBI |

| Single Item burnout Rohland et al., 2004 [29] | na | na | na | na | Unclear | B. 0.64 (−) | nr | EE | MBI |

| B. −0.26 (−) | PA | ||||||||

| B. 0.32 (−) | DP | ||||||||

| Burnout thriving- Index Gates et al., 2019 [26] | na | na | na | na | Unclear | D. 84% (+) | nr | EE | MBI |

| D. 81% (+) | PA | ||||||||

| D. 81% (+) | DP | ||||||||

| Single item burnout Dolan et al., 2015 [19] | na | na | na | na | Unclear | A. 0.92 (+) B. 0.78 (+) D. 83% (+) | na | EE | MBI |

| Internal Consistency | Reliability | Structural Validity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument (Author/Year) | Sub-Samples | Subscales | Methodological of the Studies Quality | Results Measurement Property (Rating) Cronbach’s α (Rating) | Methodological Quality | Results (Rating) | Methodological Quality | Results (Rating) A. Comparative Fit Index B. Root Mean Square Error C. Standardized Root Mean Residuals |

| Professional quality of life Scale Galiana et al., 2017 [25] | Spanish sample | Compassion satisfaction | Very good | 0.77 (+) | na | na | Very good | A. 0.94 (−) B. 0.07 (−) |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.78 (+) | |||||||

| Burnout | 0.54 (−) | |||||||

| Brazilian sample | Compassion satisfaction | Very good | 0.86 (+) | na | na | Inadequate | A. 0.94 (−) B. 0.08 (−) | |

| Secondary traumatic ttress | 0.77 (+) | |||||||

| Burnout | 0.65 (−) | |||||||

| Professional quality of life ScaleAng et al., 2020 [16] | na | Compassion satisfaction | Very good | 0.92 (+) | na | na | na | na |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.80 (+) | |||||||

| Burnout | 0.78 (+) | |||||||

| Professional quality of life ScaleHemsworth et al., 2018 [28] | Australian nurses | Compassion satisfaction | Very good | 0.90 (+) | na | na | Very good | A. 0.99 (+) B. 0.73 (−) |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.82 (+) | A. 0.98 (+) B. 0.71 (−) | ||||||

| Burnout | 0.80 (+) | A. 0.82 (−) B. 0.15 (−) | ||||||

| Canadian nurses | Compassion satisfaction | Very good | 0.91 (+) | na | na | Very good | A. 0.99 (+) B. 0.71 (−) | |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.85 (+) | A. 0.96 (+) B. 0.09 (−) | ||||||

| Burnout | 0.75 (+) | A. 0.82 (−) B. 0.15 (+) | ||||||

| Canadian palliative nurses | Compassion satisfaction | Very good | 0.87 (+) | na | na | Very good | A. 1.00 (+) B. 0.04 (−) | |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.82 (+) | A. 0.98 (+) B. 0.07 (−) | ||||||

| Burnout | 0. 69 (−) | A. 0.85 (−) B. 0.17 (+) | ||||||

| Professional quality of life Scale Samson et al., 2016 [30] | na | Compassion satisfaction | Very good | 0.87 (+) | na | na | Very good | A. 0.68 (−) B. 0.08 (−) |

| Secondary traumatic stress | 0.82 (+) | |||||||

| Burnout | 0.69 (−) | |||||||

| Professional fulfilment Trockel et al., 2018 [31] | na | Work exhaustion | Very good | 0.86 (+) | Inadequate | ? | Inadequate | ? |

| Interpersonal disengagement | 0.92 (+) | |||||||

| Burnout | 0.92 (+) | |||||||

| Professional fulfilment | 0.91 (+) | |||||||

| Professional fulfilment Fadare et al., 2021 [24] | na | Work exhaustion | Very good | 0.92 (+) | na | na | Very good | A. 0.99 (+) B. 0.08 (−) |

| Interpersonal disengagement | 0.92 (+) | A. 0.99 (+) B. 0.08 (−) | ||||||

| Professional fulfilment | 0.92 (+) | C. 0.07 (+) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Emal, L.M.; Tamminga, S.J.; Kezic, S.; Schaafsma, F.G.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; van der Molen, H.F. Diagnostic Accuracy and Measurement Properties of Instruments Screening for Psychological Distress in Healthcare Workers—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126114

Emal LM, Tamminga SJ, Kezic S, Schaafsma FG, Nieuwenhuijsen K, van der Molen HF. Diagnostic Accuracy and Measurement Properties of Instruments Screening for Psychological Distress in Healthcare Workers—A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126114

Chicago/Turabian StyleEmal, Lima M., Sietske J. Tamminga, Sanja Kezic, Frederieke G. Schaafsma, Karen Nieuwenhuijsen, and Henk F. van der Molen. 2023. "Diagnostic Accuracy and Measurement Properties of Instruments Screening for Psychological Distress in Healthcare Workers—A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126114

APA StyleEmal, L. M., Tamminga, S. J., Kezic, S., Schaafsma, F. G., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., & van der Molen, H. F. (2023). Diagnostic Accuracy and Measurement Properties of Instruments Screening for Psychological Distress in Healthcare Workers—A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126114