Modeling the Conversation with Digital Health Assistants in Adherence Apps: Some Considerations on the Similarities and Differences with Familiar Medical Encounters

Abstract

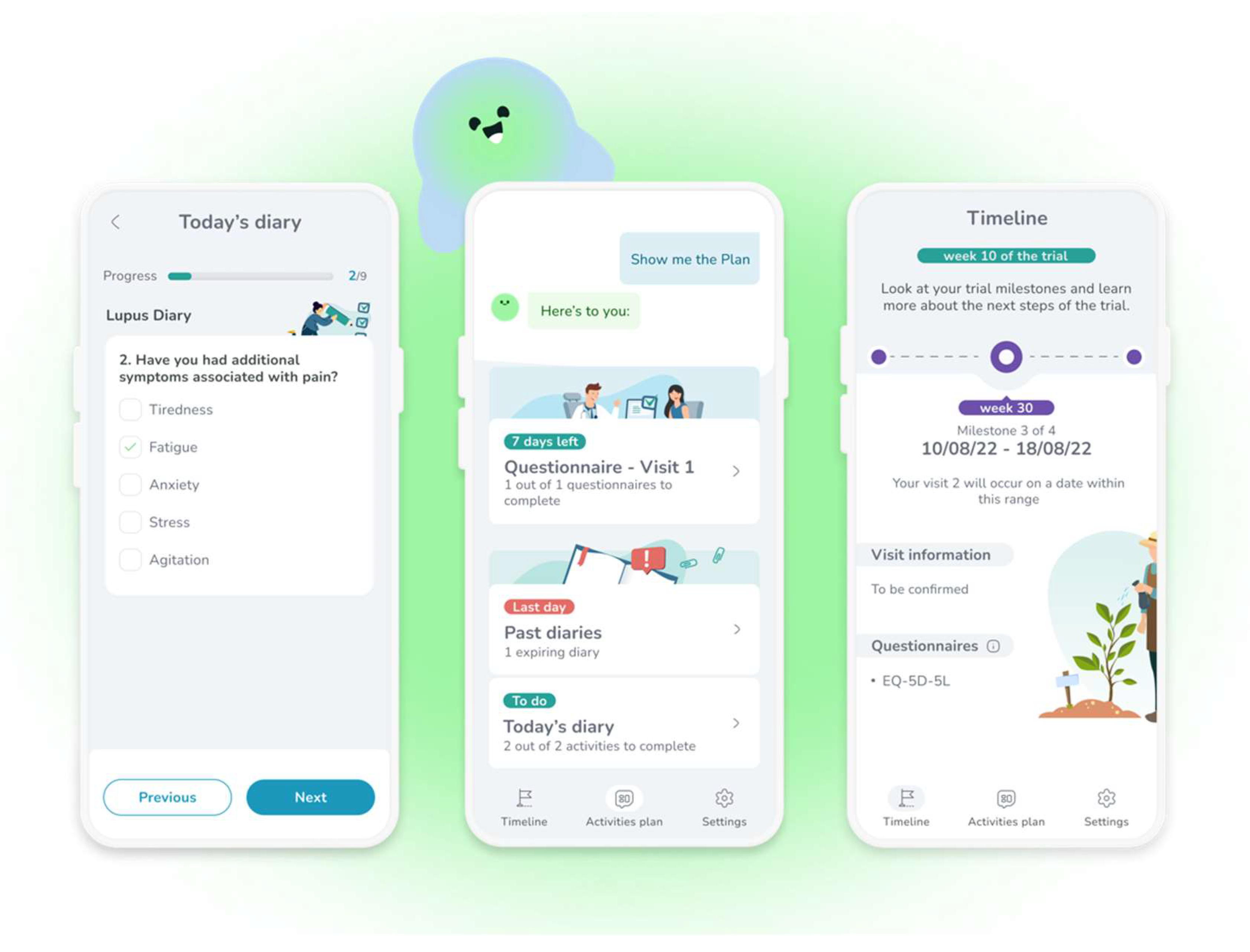

:1. Conversational Agents in Adherence Apps: Digital Health Assistants

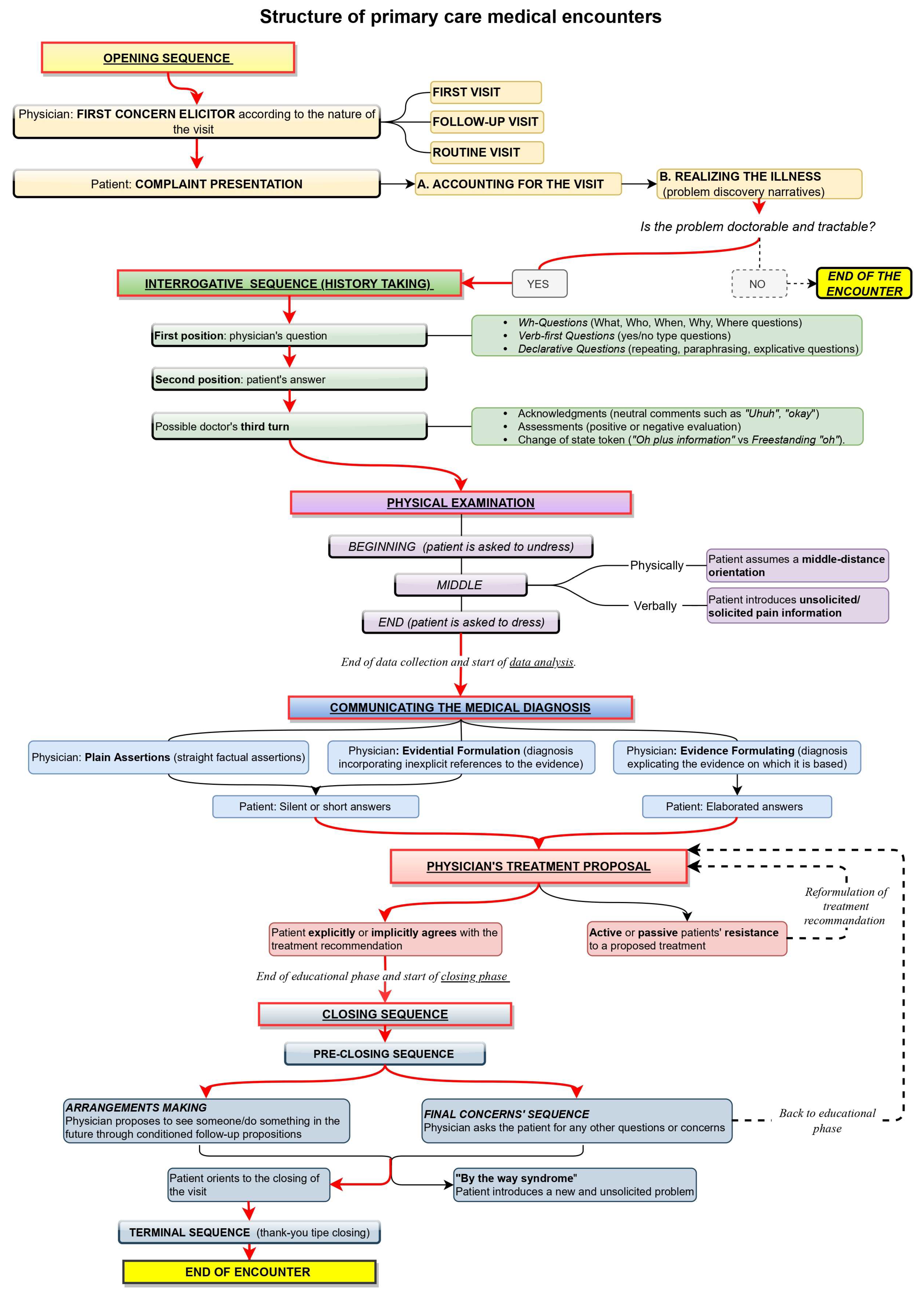

2. Similarities and Differences in the Structure of Physician- and DHA-Patient Encounters

Similarities and Differences with DHA-Patient Encounters in Adherence Apps

3. Design Recommendations Phase-by-Phase

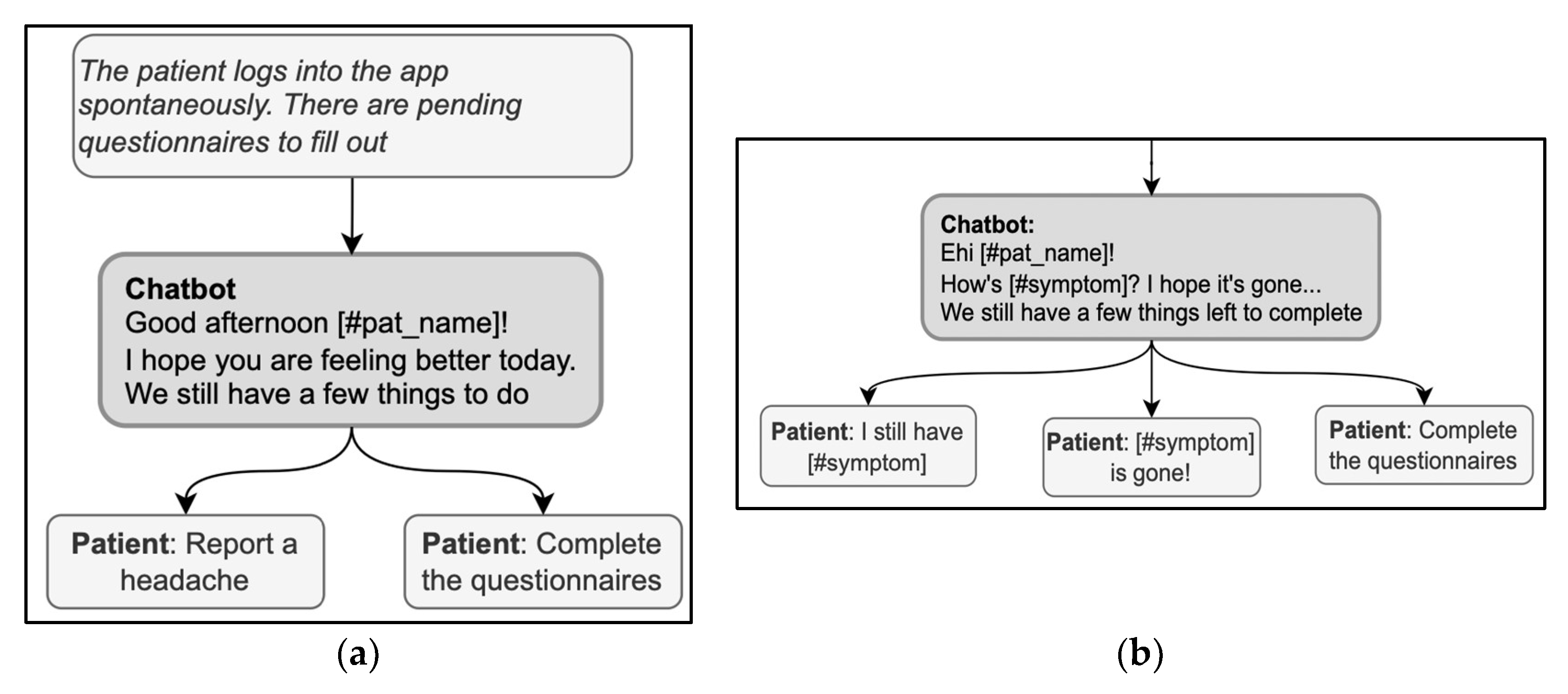

3.1. Openings

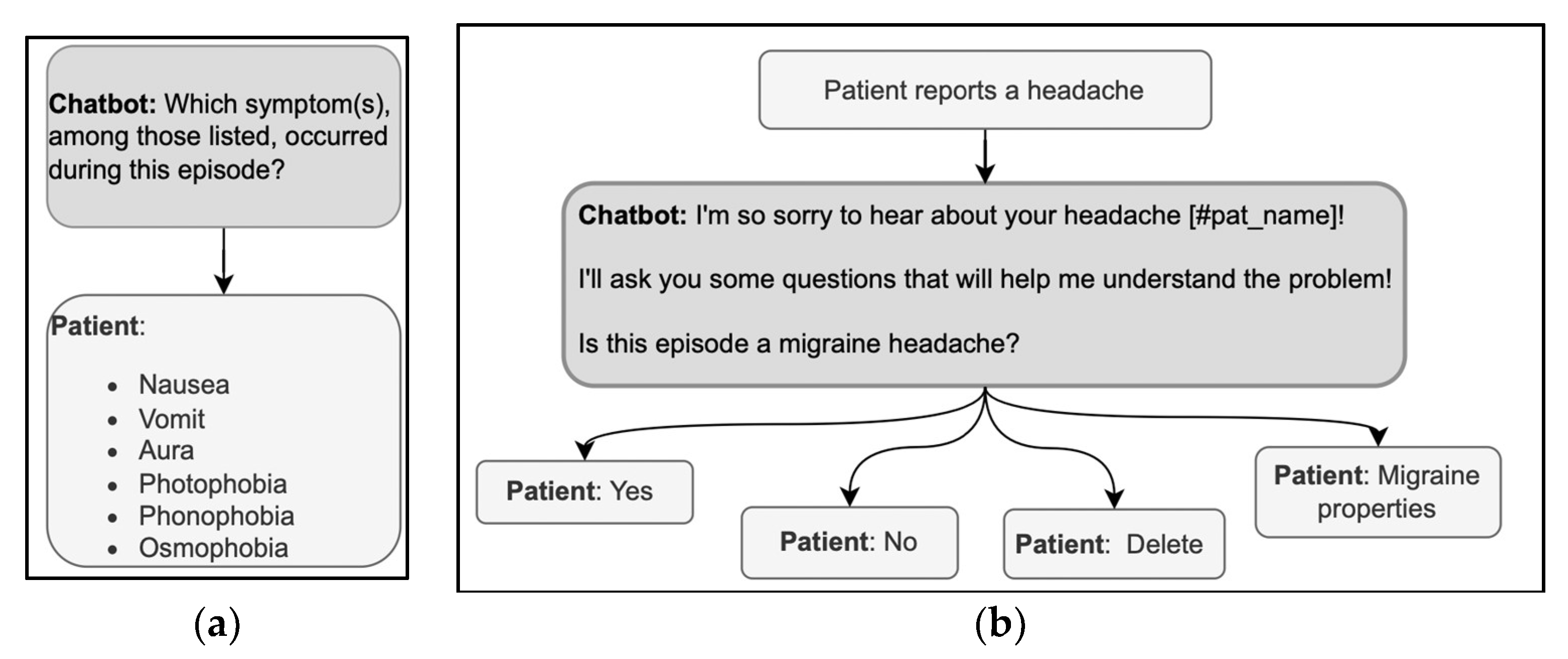

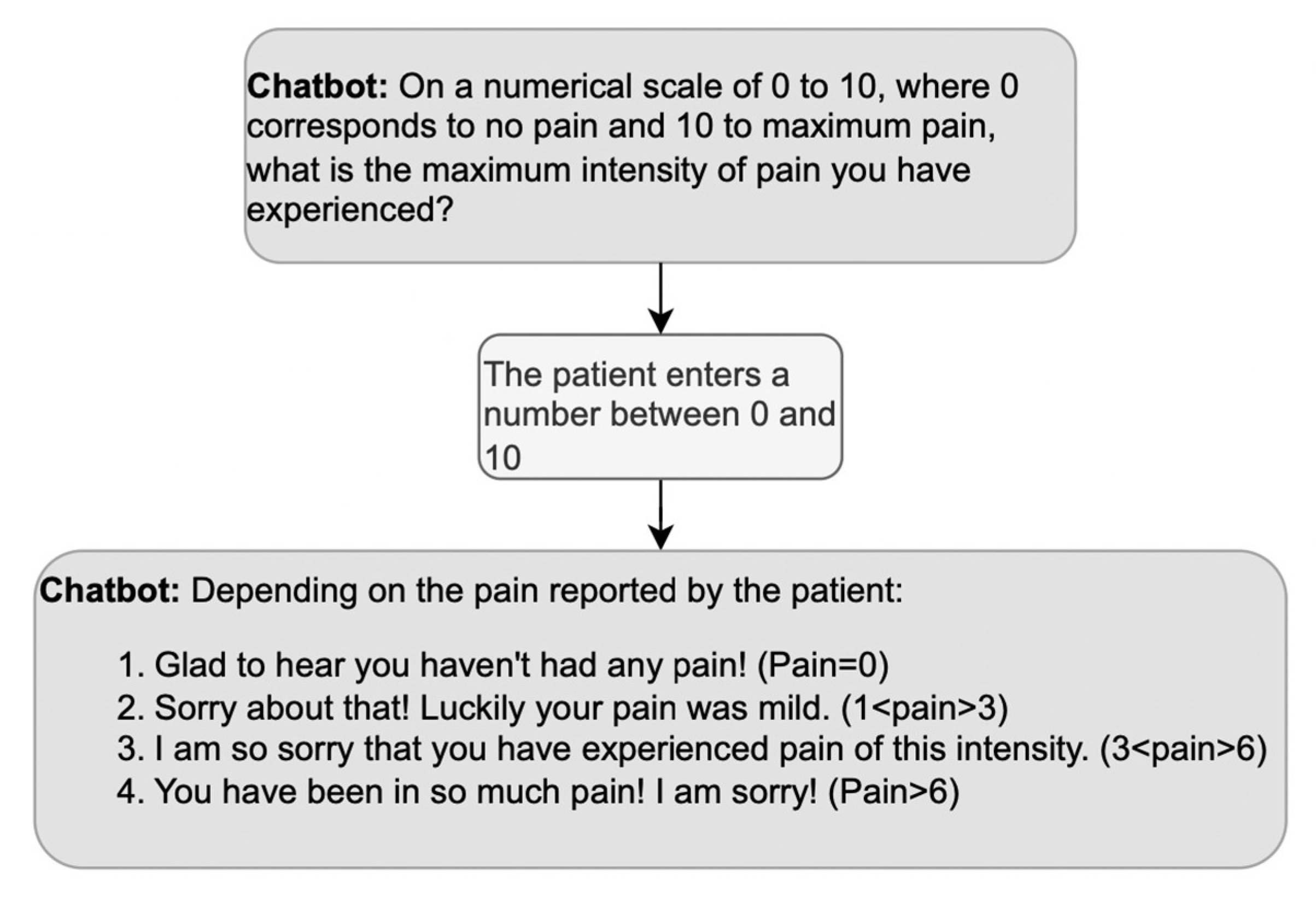

3.2. History-Taking

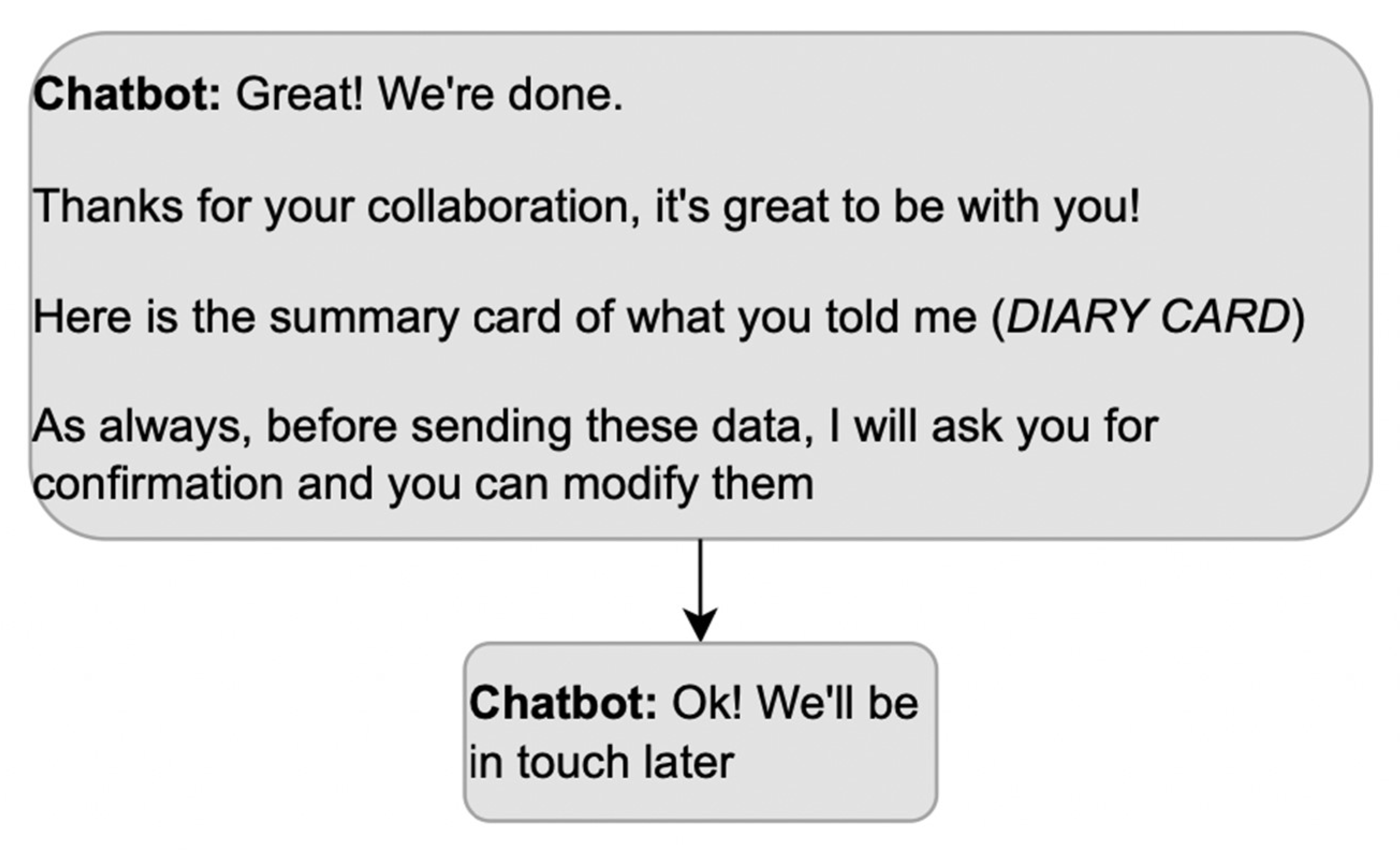

3.3. Pre-Closure and Closure

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Unconstrained Natural Language Interfaces

4.2. Chats and Emergency Calls

4.3. Limits

4.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sabatè, E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report_fin.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Vrijens, B.; De Geest, S.; Hughes, D.A.; Przemyslaw, K.; Demonceau, J.; Ruppar, T.; Dobbels, F.; Fargher, E.; Morrison, V.; Lewek, P.; et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, F.; Pobiruchin, M.; Wiesner, M.; Meixner, G. An approach to improve medication adherence by smart watches. In Digital Healthcare Empowering Europeans; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 956–958. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Sklar, G.E.; Oh, V.M.S.; Li, S.C. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ali, E.E.; Chan, S.S.L.; Leow, J.L.; Chew, L.; Yap, K.Y.-L. User acceptance of an app-based adherence intervention: Perspectives from patients taking oral anticancer medications. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 25, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anghel, L.A.; Farcas, A.M.; Oprean, R.N. An overview of the common methods used to measure treatment adherence. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2019, 92, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald, D.S.; Butt, S.; Bestwick, J.P. One-way Versus Two-way Text Messaging on Improving Medication Adherence: Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 1139.e1–1139.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabi, K.; Randhawa, A.S.; Choi, F.; Mithani, Z.; Albers, F.; Schnieder, M.; Nikoo, M.; Vigo, D.; Jang, K.; Demlova, R.; et al. Mobile Apps for Medication Management: Review and Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline: Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/digital-interventions-health-system-strengthening/en/ (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Ross, J.; Stevenson, F.; Dack, C.; Pal, K.; May, C.; Michie, S.; Barnard, M.; Murray, E. Developing an implementation strategy for a digital health intervention: An example in routine healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solomon, D.H.; Rudin, R.S. Digital health technologies: Opportunities and challenges in rheumatology. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bézie, A.; Morisseau, V.; Rolland, R.; Guillemassé, A.; Brouard, B.; Chaix, B. Using a Chatbot to Study Medication Overuse among Patients Suffering from Headaches. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 801782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Car, J.; Tan, W.S.; Huang, Z.; Sloot, P.; Franklin, B.D. eHealth in the future of medications management: Personalisation, monitoring and adherence. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Backes, C.; Moyano, C.; Rimaud, C.; Bienvenu, C.; Schneider, M.P. Digital Medication Adherence Support: Could Healthcare Providers Recommend Mobile Health Apps? Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 2, 616242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Car, L.T.; Dhinagaran, D.A.; Kyaw, B.M.; Kowatsch, T.; Joty, S.; Theng, Y.-L.; Atun, R. Conversational Agents in Health Care: Scoping Review and Conceptual Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E.; Heritage, J. Taking the Patient’s Medical History: Questioning during Comprehensive History Taking. In Communication in Medical Care: Interactions between Physicians and Patients; Heritage, J., Maynard, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 151–184. [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulou, E.; Moussiades, L. An overview of DHA technology. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, Cham, Switzerland, 17–20 June 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickmore, T.; Trinh, H.; Asadi, R.; Olafsson, S. Safety first: Conversational agents for health care. In Studies in Conversational UX Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.; Vythilingam, R.; Formosa, P. A principlist-based study of the ethical design and acceptability of artificial social agents. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2023, 172, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Ethics Guidelines For Trustworthy AI. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Jain, U. Personal Digital Health Assistants. ASA Monit. 2021, 85, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.G.; Bartel, B.; Ferguson, T.; Blake, H.T.; Northcott, C.; Virgara, R.; A Maher, C. Improving User Experience of Virtual Health Assistants: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e31737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Dunn, A.G.; Tong, H.L.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Chen, J.; Bashir, R.; Surian, D.; Gallego, B.; Magrabi, F.; Lau, A.Y.S.; et al. Conversational agents in healthcare: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Informatics Assoc. 2018, 25, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chew, H.S.J. The Use of Artificial Intelligence–Based Conversational Agents (Chatbots) for Weight Loss: Scoping Review and Practical Recommendations. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 10, e32578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Ji, M.; Xie, W.; Qian, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Hao, T. Language Use in Conversational Agent–Based Health Communication: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e37403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, J. Conversation analysis and institutional talk. In Handbook of Language and Social Interaction; Fitch, K.L., Sanders, R.E., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 103–148. [Google Scholar]

- Arminen, I.; Licoppe, C.; Spagnolli, A. Respecifying Mediated Interaction. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 2016, 49, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchby, I. Technologies, Texts and Affordances. Sociology 2001, 35, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, J.; Maynard, D.W. (Eds.) Communication in Medical Care: Interaction between Primary Care Physicians and Patients; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, C. The opening sequence in doctor-patient interaction. In Medical Work: Realities and Routines; Atkinson, P., Heath, C., Eds.; Gower: Farnborough, UK, 1981; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.D. An Interactional Structure of Medical Activities during Acute Visits and Its Implications for Patients’ Participation. Health Commun. 2003, 15, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, D.W.; Heritage, J. Conversation analysis, doctor-patient interaction and medical communication. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heritage, J.; Maynard, D.W. Problems and Prospects in the Study of Physician-Patient Interaction: 30 Years of Research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2006, 32, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Button, G.; Casey, N. Generating a topic: The use of topic initial elicitors. In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis; Atkinson, J.M., Heritage, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.D. Soliciting patients’ presenting concerns. In Communication in Medical Care: Interaction between Physicians and Patients; Heritage, J., Maynard, D.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gafaranga, J.; Britten, N. “Fire away”: The opening sequence in general practice consultations. Fam. Pract. 2003, 20, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gafaranga, J.; Britten, N. Talking an institution into being: The opening sequence in general practice consultations. In Applying Conversation Analysis; Richards, K., Seedhouse, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckle, J.D.; Billings, J.A. A history of history-taking. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1987, 2, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, V.T. Doing Attributions in Medical Interaction: Patients’ Explanations for Illness and Doctors’ Responses. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppermann, A.; Spranz-Fogasy, T. Doctors’ Questions as Displays of Understanding. Commun. Med. 2011, 8, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, H.H.; Schaefer, E.F. Contributing to discourse. Cogn. Sci. 1989, 13, 259–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, C. Demonstrative Suffering: The Gestural (Re)embodiment of Symptoms. J. Commun. 2002, 52, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Have, P. Talk and institution: A reconsideration of the ‘asymmetry’ of doctor-patient interaction. In Talk and Social Structure: Studies in Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis; Boden, D., Zimmerman, D.H., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; pp. 138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Spranz-Fogasy, T. Verstehensdokumentation in der medizinischen kommunikation: Fragen und Antworten im Arzt-Patient-Gespräch. In Verstehen in professionellen Handlungsfeldern; Deppermann, A., Reitemeier, U., Schmitt, R., Spranz-Fogasy, T., Eds.; Narr: Tübingen, Germany, 2010; pp. 27–116. [Google Scholar]

- Perakyla, A. Authority and Accountability: The Delivery of Diagnosis in Primary Health Care. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S.; Antaki, C. How professionals deal with clients’ explicit objections to their advice. Discourse Stud. Interdiscip. J. Study Text Talk 2022, 24, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, V.; Parry, R.; Seymour, J. Communication practices that encourage and constrain shared decision making in health-care encounters: Systematic review of conversation analytic research. Health Expect. 2017, 20, 1228–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.D. Closing medical encounters: Two physician practices and their implications for the expression of patients’ unstated concerns. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C. Coordinating closings in primary care visits: Producing continuity of care. Stud. Interact. Socioling. 2006, 20, 379–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. Negotiating last-minute concerns in closing Korean medical encounters: The use of gaze, body and talk. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.J. Closing Surgeon-Patient Consultations. Int. Rev. Pragmat. 2012, 4, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.J. Closing clinical consultations. In Handbuch Sprache in der Medizin; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.B. “If you don’t get better, you may come back here”: Proposing conditioned follow-ups to the doctor’s office. Text Talk 2018, 38, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, G.; Holden, J. The time-efficiency principle: Time as the key diagnostic strategy in primary care. Fam. Pract. 2013, 30, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, J.; Levinson, W.; Roter, D. Oh, by the way …. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1994, 9, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.C.; Rosson, C.; Christensen, J.; Hart, R.; Levinson, W. Wrapping things up: A qualitative analysis of the closing moments of the medical visit. Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 30, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, P.; Long, B. Doctors Talking to Patients: A Study of the Verbal Behaviours of Doctors in the Consultation; Her Majesty’s Stationery Office: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, R.M. From sentence to sequence: Understanding the medical encounter through microinteractional analysis. Discourse Process. 1984, 7, 135–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolli, A.; Gamberini, L.; D’Agostini, E.; Cenzato, G. Understanding the Stakeholders’ Expectations About an Adherence App: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Bari, Italy, 30 August–3 September 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sidnell, J. Conversation Analysis: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.D. The Organization of Action and Activity in General Practice, Doctor-Patient Consultations. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Footing. Semiotica 1979, 25, 1–29. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/semi.1979.25.1-2.1/html (accessed on 3 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cassell, E.J. Talking with Patients; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, J.; Clayman, S. Talk in Action: Interactions, Identities, and Institutions; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y.; Carney, P. Are People Polite to Computers? Responses to Computer-Based Interviewing Systems1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 1093–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y. Machines and Mindlessness: Social Responses to Computers. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivers, T.; Heritage, J. Breaking the sequential mold: Answering ‘more than the question’ during comprehensive history taking. Text Talk 2001, 21, 151–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvel, M.K.; Epstein, R.M.; Flowers, K.; Beckman, H.B. Soliciting the Patient’s Agenda. JAMA 1999, 281, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kocaballi, A.B.; Coiera, E.; Berkovsky, S. Revisiting habitability in conversational systems. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–28 April 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Følstad, A.; Taylor, C. Conversational Repair in Chatbots for Customer Service: The Effect of Expressing Uncertainty and Suggesting Alternatives. In Proceedings of the Chatbot Research and Design: Third International Workshop, CONVERSATIONS 2019, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 19–20 November 2019; Revised Selected Papers. Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schegloff, E.A.; Jefferson, G.; Sacks, H. The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language 1977, 53, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakin, M.A.; Zimmerman, D.H. Reduction and Specialization in Emergency and Directory Assistance Calls. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 1999, 32, 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromdal, J.; Landqvist, H.; Persson-Thunqvist, D.; Osvaldsson, K. Finding out what’s happened: Two procedures for opening emergency calls. Discourse Stud. 2012, 14, 371–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hedman, K. Managing Medical Emergency Calls (Doctoral dissertation, Lund University Open Access). 2016. Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hj:diva-34568 (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Ranjbartabar, H.; Richards, D.; Bilgin, A.A.; Kutay, C. First Impressions Count! The Role of the Human’s Emotional State on Rapport Established with an Empathic versus Neutral Virtual Therapist. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 12, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.; Richards, D. Modelling Therapeutic Alliance Using a User-Aware Explainable Embodied Conversational Agent to Promote Treatment Adherence. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th ACM In-ternational Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Paris, France, 2–5 July 2019; ACM: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 248–251. [Google Scholar]

| Opening | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Does the caller explain the reason for the encounter at the opening (or re-opening after a pre-closure)? If the reason is not stated immediately, is it explicitly solicited by the called party within the opening phase? Alternatively, is the reason known to both parties (i.e., there is no other possible reason than one)? |

| 1a | When the patient is the caller, does the DHA use a first concern elicitor, and is the answer to the first concern elicitor present and explicit? |

| 1b | In DHAs using predefined answer options, do the answer options to the first concern elicitor cover all possible reasons for the visit? |

| 2 | Does the DHA address the patient in a way that acknowledges the recurrent nature of their encounters? For instance, by addressing them by their name, referring to their last encounter, or (if appropriate to the reason for the encounter) when the data was last collected |

| 2a | Is the DHA’s first concern elicitor appropriate for the type of visit that is about to take place? (Note: If the activation of the DHA is a general one, without any clue about the reason for the visit, the first concern elicitor should be as vague as “What can I do for you?”; if some activities were postponed and need to be resumed as soon as the patient feels better, the first concern elicitor can be “How are you now?”) |

| 3 | Can the DHA’s initial greetings (how are you) be confused with a first concern elicitor, or does it specifically refer to the patient’s last reported condition or agreement? |

| 3a | Does the DHA use one elicitor per message? |

| 3b | Are the response options relevant (consistent) for the corresponding elicitor? |

| History taking | |

| 4 | Does the DHA begin an interrogation sequence only after completing the opening phase? |

| 5 | Does the DHA use Wh-questions to collect information it does not have and V1-Questions only for information already inputted and needing confirmation? |

| 5a | Is the patient allowed to correct their inputted data at any point in the conversation, including right after inputting them? |

| 5b | Does the DHA clarify what it does with the data and react empathically to the inputted data? |

| 6 | Does the DHA clarify the criterion, which makes some answers irrelevant (and then not present) among the answer options? |

| 7 | Does the DHA avoid formulating the question in a way that makes an optimistic answer desirable? |

| Closing | |

| 8 | Is there after history taking a pre-closing sequence (opened by DHA) that… |

| 8a | … allows the patient to confirm what has been communicated to the DHA? |

| 8b | …mentions or agrees about when (or if) the meeting will be repeated and for which activity? |

| 8c | …offers the patient to carry out another activity instead of closing the encounter? |

| 9 | Is there a sequence that explicitly ends the encounter with thanks and greetings? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spagnolli, A.; Cenzato, G.; Gamberini, L. Modeling the Conversation with Digital Health Assistants in Adherence Apps: Some Considerations on the Similarities and Differences with Familiar Medical Encounters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126182

Spagnolli A, Cenzato G, Gamberini L. Modeling the Conversation with Digital Health Assistants in Adherence Apps: Some Considerations on the Similarities and Differences with Familiar Medical Encounters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(12):6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126182

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpagnolli, Anna, Giulia Cenzato, and Luciano Gamberini. 2023. "Modeling the Conversation with Digital Health Assistants in Adherence Apps: Some Considerations on the Similarities and Differences with Familiar Medical Encounters" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 12: 6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126182

APA StyleSpagnolli, A., Cenzato, G., & Gamberini, L. (2023). Modeling the Conversation with Digital Health Assistants in Adherence Apps: Some Considerations on the Similarities and Differences with Familiar Medical Encounters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20126182