Access to Healthcare Services among Thai Immigrants in Japan: A Study of the Areas Surrounding Tokyo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

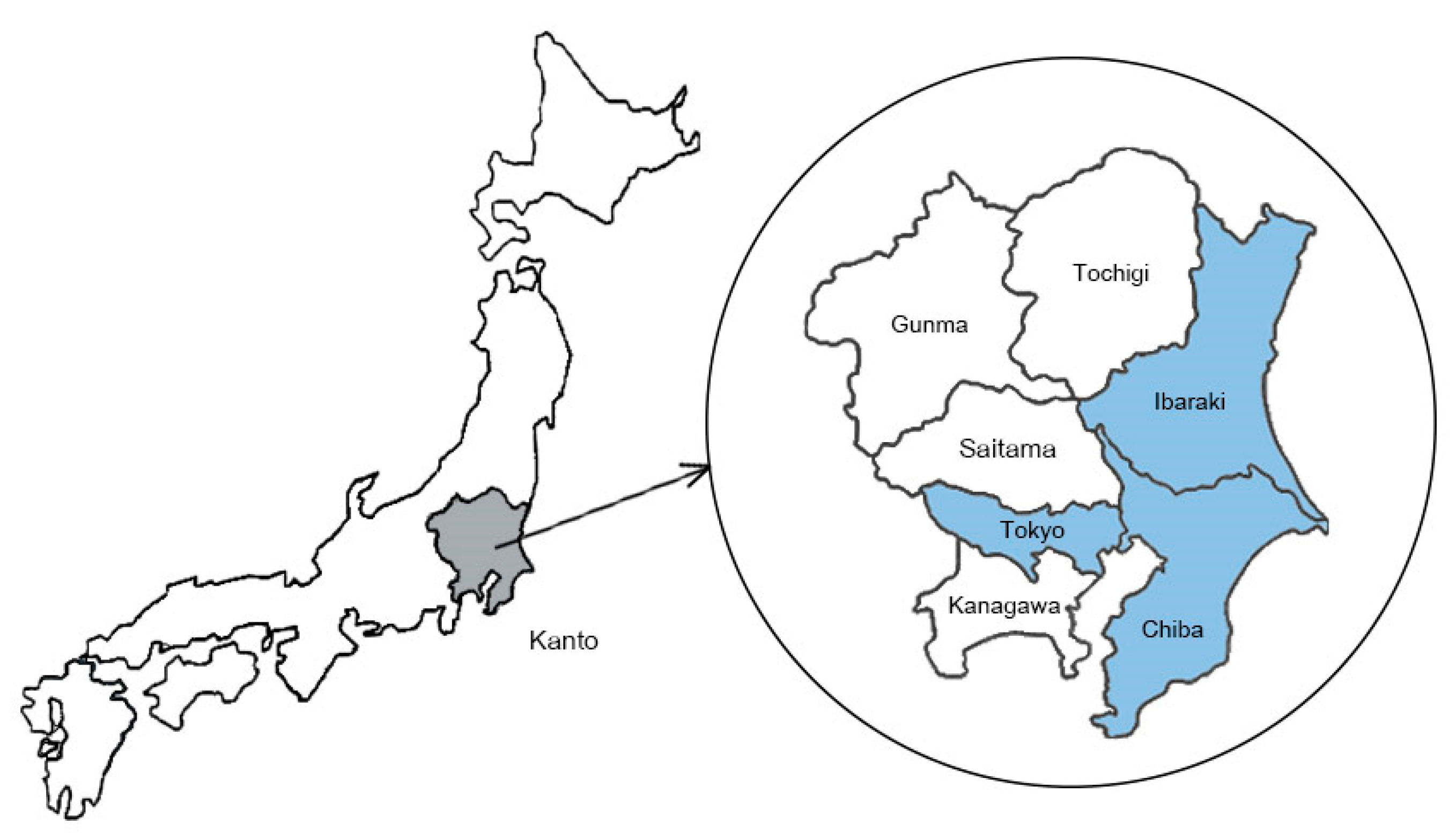

2.1. Study Setting, Sample Size, and Data Collection

2.2. Variable Measurements: Dependent Variables

2.3. Variable Measurements: Independent Variables

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Ethics and Consent

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vargas-Silva, C. Migration and Development-Migration Observatory; Migration Observatory. Available online: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/primers/migration-and-development/ (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- World Health Organization. Refugee and Migrant Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/refugee-and-migrant-health (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- OECD. Japan. In International Migration Outlook 2020, 44th ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 206–207. [Google Scholar]

- SDGs Promotion Headquarters. SDGs Implementation Guiding Principles Revised Edition (Temporary Translation). 2016. Available online: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/sdgs/pdf/jisshi_shishin_r011220e.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Derose, K.P.; Escarce, J.J.; Lurie, N. Immigrants And Health Care: Sources Of Vulnerability. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacker, K.; Anies, M.; Folb, B.L.; Zallman, L. Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: A literature review. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2015, 8, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Migration, Health & Human Rights; World Health Organization: Paris, France, 2003; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Internations. Guide to Health Insurance and Healthcare System in Japan; InterNations. Available online: https://www.internations.org/japan-expats/guide/healthcare (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- World Health Organization. UHC Law in Practice: Legal access Rights to Health Care: Country Profile: Japan; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ken Uzuka. Uninsured Foreigners in Japan Face Threats to Life. Mainichi Daily News. 20 November 2021. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20211120/p2a/00m/0na/021000c (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Nikkei Asia. Foreigners’ Unpaid Bills Give Japanese Hospitals a Headache. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-immigration/Foreigners-unpaid-bills-give-Japanese-hospitals-a-headache2 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Supakul, S.; Ozaki, A.; Tanimoto, T. A Call for Enhanced Healthcare Support for Increasingly Vulnerable Groups of Foreigners in Japan: Insights from a Former Thai-Native Medical Student in Japan. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 28, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistic Bureau of Japan. News Bulletin 28 February 2022. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/info/news/20220228.html (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Japan-Thailand Relations. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/thailand/data.html (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan. Statistics. Available online: https://www.isa.go.jp/en/policies/statistics/index.html (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- World Health Organization. Distribution of Health Payments and Catastrophic Expenditures Methodology/by Ke Xu; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. SDG 3.8.2 Catastrophic Health Spending (and Related Indicators). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/financial-protection (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Calderon, J.; Rijks, B.; Agunias, D.R. Asian labour migrants and health: Exploring policy routes. Int. Organ. Migr. Issue Brief 2012, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Li, N. Empirical Analysis of the Status and Influencing Factors of Catastrophic Health Expenditure of Migrant Workers in Western China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Dong, D. Association of migration status with quality of life among rural and urban adults with rare diseases: A cross-sectional study from China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1030828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, K.; Mahmud, A.; Hamedon, T.R. Incidence and determinants of catastrophic health expenditure among low-income Malaysian households. Med. J. Malays. 2022, 77, 474–480. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, S.; Sata, M.; Rosenberg, M.; Nakagoshi, N.; Kamimura, K.; Komamura, K.; Kobayashi, E.; Sano, J.; Hirazawa, Y.; Okamura, T.; et al. Universal health coverage in the context of population ageing: Catastrophic health expenditure and unmet need for healthcare. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, T.; Ceelen, M.; Tang, M.J.; Browne, J.L.; de Keijzer, K.J.; Buster, M.C.; Das, K. Health care seeking among detained undocumented migrants: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imafuku, R.; Nagatani, Y.; Shoji, M. Communication Management Processes of Dentists Providing Healthcare for Migrants with Limited Japanese Proficiency. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, J.; Tylleskär, T.; Sontag, K.; Peterhans, B.; Ritz, N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries-the 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattof, S.R. Health insurance and care-seeking behaviours of female migrants in Accra, Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P. Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: A systematic review through providers’ lens. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzúrová, D.; Winkler, P.; Drbohlav, D. Immigrants’ access to health insurance: No equality without awareness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7144–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müllerschön, J.; Koschollek, C.; Santos-Hövener, C.; Kuehne, A.; Müller-Nordhorn, J.; Bremer, V. Impact of health insurance status among migrants from sub-Saharan Africa on access to health care and HIV testing in Germany: A participatory cross-sectional survey. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2019, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, M.; Endo, M.; Yoshino, A. Factors associated with access to health care among foreign residents living in Aichi Prefecture, Japan: Secondary data analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Basic Design for Peace and Health (Global Health Cooperation); 2015. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000110234.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Co-Organizers of the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Forum. Universal Health Coverage Forum Tokyo Declaration on Universal Health Coverage: All Together to Accelerate Progress towards UHC. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000317581.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Japan International Cooperation Agency. Japan’s Experiences in Public Health and Medical Systems. In Chapter 5 Infectious Diseases Control; Japan International Cooperation Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, B.H.; van Ginneken, E. Health care for undocumented migrants: European approaches. Issue Brief (Commonw. Fund) 2012, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.L.; Brown, T.B. EMTALA: The Evolution of Emergency Care in the United States. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 45, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onarheim, K.H.; Melberg, A.; Meier, B.M.; Miljeteig, I. Towards universal health coverage: Including undocumented migrants. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Razum, O. Effect of restricting access to health care on health expenditures among asylum-seekers and refugees: A quasi-experimental study in Germany, 1994–2013. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immigration Services Agency. Guidebook on Living and Working: For Foreign Nationals Who Start Living in Japan. Available online: https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001297615.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Maillard-Belmonte, R. Foreigners without Residency Status Fear for Their Lives. Available online: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/2041/ (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Yuka Honda. Medical Expenses of 22 Million Yen for One Foreign Patient Cannot Be Recovered Tokyo Metropolitan Hiroo Hospital. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASQ9H2V2YQ9GOXIE01T.html (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Sugie, Y.; Kodama, T. Immigrant Health Issue in Japan-The Global Contexts and a Local Response to the Issue. 2017. Available online: http://jupiter2.jiu.ac.jp/books/bulletin/2013/nurse/01_sugie.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Thwin, A.A.; Patcharanarumol, W. Implementing health insurance for migrants, Thailand. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Evolution and complexity of government policies to protect the health of undocumented/illegal migrants in Thailand-the unsolved challenges. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2017, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinmann, T.; AlZahmi, A.; Schneck, A.; Mancera Charry, J.F.; Fröschl, G.; Radon, K. Population-based assessment of health, healthcare utilisation, and specific needs of Syrian migrants in Germany: What is the best sampling method? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Population (n = 67) | Unspecified Visa Status (n = 22) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 43 | 64.2 | 10 | 45.5 | |

| Male | 24 | 35.8 | 12 | 54.5 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20–29 | 18 | 26.9 | 13 | 59.1 | |

| 30–39 | 8 | 11.9 | 4 | 18.2 | |

| 40–49 | 15 | 22.4 | 4 | 18.2 | |

| 50–59 | 19 | 28.4 | 1 | 4.5 | |

| ≥60 | 7 | 10.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Educational level | |||||

| Elementary school or lower | 18 | 26.9 | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Junior high school | 15 | 22.4 | 7 | 31.8 | |

| Highschool | 20 | 29.9 | 10 | 45.5 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or upper | 14 | 20.9 | 3 | 13.6 | |

| Hometown | |||||

| Northeast | 29 | 43.3 | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Central | 16 | 23.9 | 5 | 22.7 | |

| East | 7 | 10.4 | 11 | 50 | |

| North | 12 | 17.9 | 4 | 18.2 | |

| South | 3 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Duration of stay | |||||

| <6 months | 7 | 10.4 | 5 | 22.7 | |

| 6 months–5 years | 23 | 34.3 | 12 | 54.5 | |

| ≥5 years | 37 | 55.2 | 5 | 22.7 | |

| Japanese language proficiency | |||||

| less than N5 | 11 | 16.4 | 5 | 22.7 | |

| N5 | 20 | 29.9 | 12 | 54.5 | |

| N4 | 12 | 17.9 | 3 | 13.6 | |

| N3 | 16 | 23.9 | 2 | 9.1 | |

| N2 | 5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| N1 | 3 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Type of visa | |||||

| Short term | 4 | 6 | |||

| Long term | 41 | 61.2 | |||

| Unspecified | 22 | 32.8 | |||

| Total Population (n = 67) | Unspecified Visa Status (n = 22) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Full-time employed | 49 | 73.1 | 21 | 95.5 | |

| Unemployed | 8 | 11.9 | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Business owner | 5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Part-time employed | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Household income (100,000 Japanese yen/year) | |||||

| <19 | 15 | 22.4 | 3 | 13.6 | |

| 20–39 | 33 | 49.3 | 15 | 68.2 | |

| 40–59 | 11 | 16.4 | 3 | 13.6 | |

| 60–79 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| ≥80 | 6 | 8.9 | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Out-of-pocket (OOP) (100,000 Japanese yen/year) | |||||

| <4 | 43 | 64.2 | 11 | 50 | |

| 4.1–8 | 15 | 22.4 | 7 | 31.8 | |

| 8–12 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 13.6 | |

| 12.1–16 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 40 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 4.5 | |

| Catastrophic healthcare expenditure (CHE) | |||||

| No CHE | 63 | 94 | 20 | 90.9 | |

| Have CHE | 4 | 6 | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Total Population (n = 67) | Unspecified Visa Status (n = 22) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % |

| Insurance type | ||||

| National Health Insurance (NHI) | 25 | 37.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Social Insurance (SI) | 13 | 19.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 2 | 3 | 2 | 9.1 |

| None | 27 | 40.3 | 20 | 90.9 |

| Health status | ||||

| Chronic diseases | 28 | 41.8 | 4 | 18.2 |

| No chronic diseases | 39 | 58.2 | 18 | 81.8 |

| Health information access | ||||

| Language used when receiving healthcare services | ||||

| Thai | 6 | 9 | 4 | 18.2 |

| Japanese | 53 | 79.1 | 16 | 72.7 |

| English | 5 | 7.5 | 1 | 4.5 |

| Other | 3 | 4.5 | 1 | 4.5 |

| Source of information | ||||

| Non-governmental SNS sources | 24 | 35.8 | 7 | 31.8 |

| Governmental SNS sources | 8 | 11.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Television/radio/newspaper | 7 | 10.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Friends/family members | 27 | 40.3 | 10 | 45.5 |

| Employers | 15 | 22.4 | 10 | 45.5 |

| Other | 7 | 10.4 | 1 | 4.5 |

| Health insurance knowledge | ||||

| Do you know that health insurance can help | ||||

| reduce the healthcare costs? | ||||

| Yes | 55 | 82.1 | 14 | 63.6 |

| No | 12 | 17.9 | 8 | 36.4 |

| Health insurance attitude | ||||

| Do you think that having health insurance is necessary? | ||||

| Necessary | 63 | 94 | 19 | 86.4 |

| Not necessary | 4 | 6 | 3 | 13.6 |

| Health insurance barriers | ||||

| Language | 20 | 29.9 | 12 | 54.5 |

| Financial | 16 | 23.9 | 9 | 40.9 |

| Complicated procedure | 5 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Time constraint | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 9.1 |

| Not necessary | 3 | 4.5 | 1 | 4.5 |

| No visa | 6 | 9 | 4 | 18.2 |

| No barrier | 33 | 49.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Variable | CHE | Knowledge HI | Attitude HI | Practice HI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | p-Value | X2 Test p-Value | aOR | 95% CI | p-Value | X2 Test p-Value | aOR | 95% CI | p-Value | X2 Test p-Value | aOR | 95% CI | p-Value | X2 Test p-Value | |

| Educational level | ||||||||||||||||

| Junior high school or lower | ||||||||||||||||

| High school or higher | 0.98 | 0.13–7.60 | 0.984 | 0.975 | 11.85 | 1.87–75.23 | 0.009 | 0.014 | 0.45 | 0.04–5.44 | 0.533 | 0.317 | 1.366 | 0.27–6.99 | 0.708 | 0.686 |

| Duration of stay | ||||||||||||||||

| <5 years | ||||||||||||||||

| ≥5 years | 0.28 | 0.02–3.44 | 0.316 | 0.21 | 16.85 | 1.61–176.62 | 0.025 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.05–5.93 | 0.615 | 0.828 | 5.72 | 1.20–27.27 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Visa | ||||||||||||||||

| Have a visa | ||||||||||||||||

| Unspecified | 1.24 | 0.13–11.52 | 0.851 | 0.451 | 0.59 | 0.02–1.08 | 0.059 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.01–1.64 | 0.112 | 0.064 | 0.02 | 0.00–0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Supakul, S.; Jaroongjittanusonti, P.; Jiaranaisilawong, P.; Phisalaphong, R.; Tanimoto, T.; Ozaki, A. Access to Healthcare Services among Thai Immigrants in Japan: A Study of the Areas Surrounding Tokyo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136290

Supakul S, Jaroongjittanusonti P, Jiaranaisilawong P, Phisalaphong R, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. Access to Healthcare Services among Thai Immigrants in Japan: A Study of the Areas Surrounding Tokyo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(13):6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136290

Chicago/Turabian StyleSupakul, Sopak, Pichaya Jaroongjittanusonti, Prangkhwan Jiaranaisilawong, Romruedee Phisalaphong, Tetsuya Tanimoto, and Akihiko Ozaki. 2023. "Access to Healthcare Services among Thai Immigrants in Japan: A Study of the Areas Surrounding Tokyo" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 13: 6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136290

APA StyleSupakul, S., Jaroongjittanusonti, P., Jiaranaisilawong, P., Phisalaphong, R., Tanimoto, T., & Ozaki, A. (2023). Access to Healthcare Services among Thai Immigrants in Japan: A Study of the Areas Surrounding Tokyo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136290