The Association of Moral Injury and Healthcare Clinicians’ Wellbeing: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

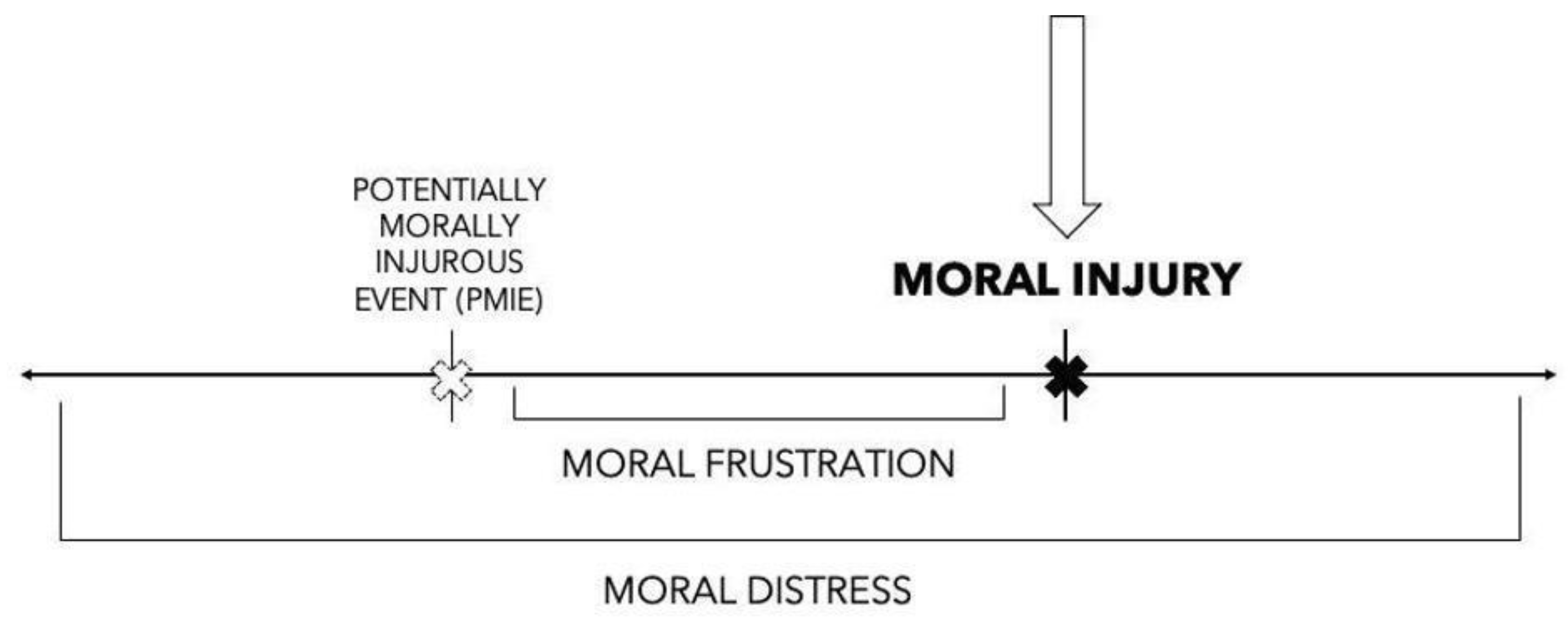

1.1. Moral Injury as a Measure of Wellbeing

1.2. Wellbeing Indicators for Healthcare Workers

1.3. Positionality Statement

1.4. Purpose

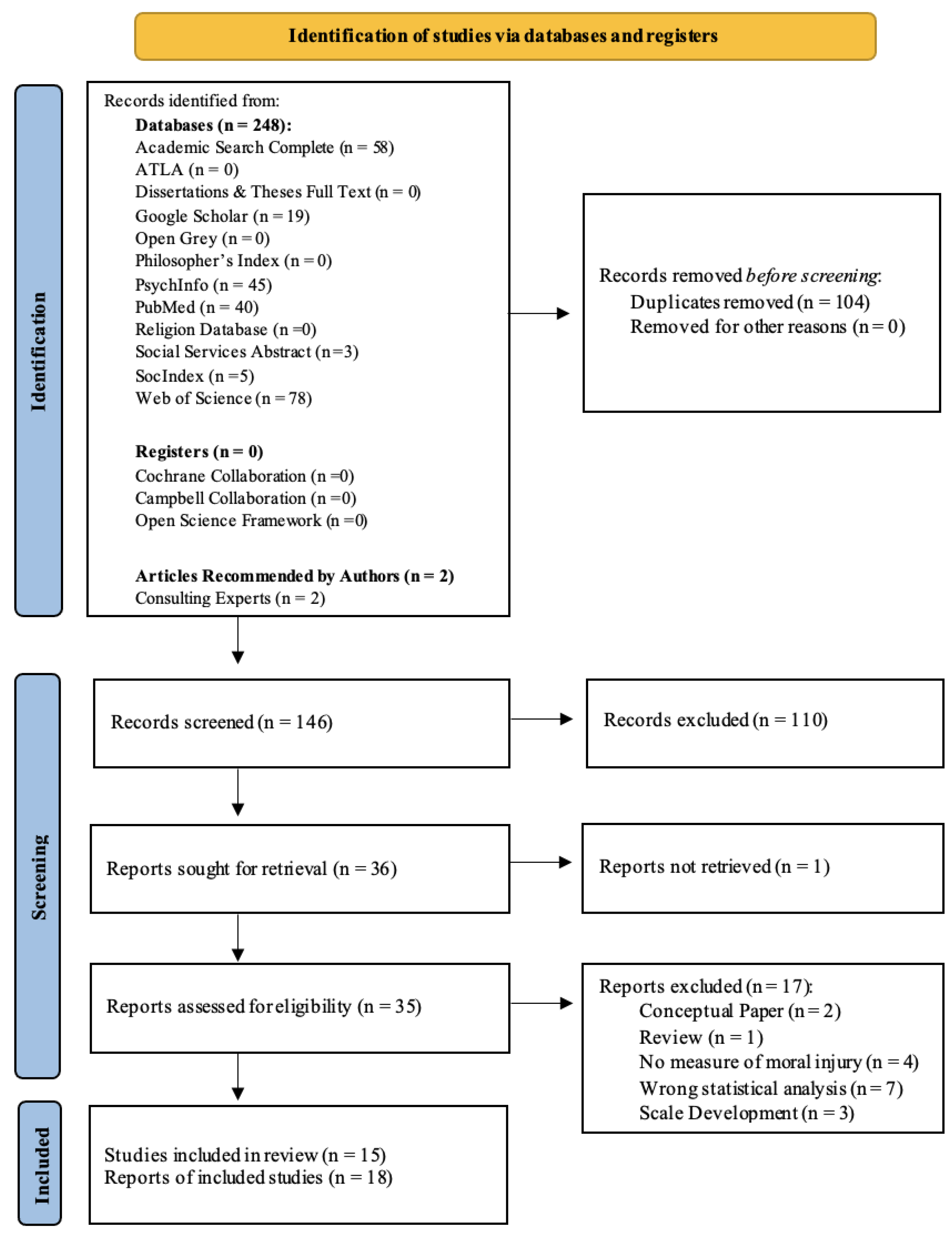

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PRISMA-P Protocol Overview

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Synthesis of Moral Injury and Wellbeing

3.3. Qualitative Studies Summary

| Authors Year Location | Aims | Sample (Size, Description, and Method) | Methodology/ Design/ Theory | Concepts Studied (Variables) | Outcomes | Conclusion about Moral Injury and Wellbeing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander 2020 [44] United States | To offer an illustration of how moral injury interventions with veteran populations can inform care for physicians experiencing burnout. | n = 1 Female cardiologist with 20+ years clinical experience. Convenience Sampling | Qualitative Case Study Content Analysis No use of theory | Moral Injury (Shay’s Definition) Personal Wellbeing Compassion Fatigue Emotions Burnout | Themes: Use of clinical terms is not helpful in describing distress. Need to address the moral declination that impacts her personal wellbeing and work. Examination of all identities is essential. “Polarization” must be named in work vs. personal conflict. | Moral injury impacts personal wellbeing (adverse personal emotions, high stress, and polarization between work/personal life and beliefs) as well as professional wellbeing (burnout, compassion fatigue, and increased cynicism). |

| Ball, Watsford, and Scholz 2020 [45] Australia | To analyze these data with regard to positive and harmful ways trainees have been impacted by their clinical work. | n = 14 Majority female (n = 11) psychologists in a medical center during the second year of their training program. Purposive Sampling | Qualitative Phenomenological Cross-sectional, semi-structured interviews Thematic Analysis [61] Recommended Biopsychosocial-spiritual model for theory. | Moral Injury (MI) [59] Vicarious Trauma (VT) Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) Compassion Fatigue (CF) Burnout | Themes: Engagement with training and professional selves. Engagement with training and holistic selves. Self-Care | Trauma exposure could lead to STS, VT, and MI. MI can occur prior or alongside CF, and then burnout is a result of all these experiences. |

| Benatov, Zerach, and Levi-Belz 2022 [48] Israel | To examine the moderating role of thwarted belongingness in the relationships between HCWs’ exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) and moral injury symptoms, depression, and anxiety. | n = 296 Majority female, Israeli-born, and married. Mean age of 40.28 years, and included nurses, doctors, social and psychological care workers, and clinical support workers who mostly worked in hospitals. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Cross-sectional Linger Regression Mediation-Moderation Modeling [62] Lietz’s framework of moral injury named in discussion [63]. | Moral Injury MISS-HP Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs) MIES Anxiety GAD-7 Depression PHQ-9 Belongingness Thwarted Belongingness (TB) | Moral injury was positively correlated with anxiety, depression, PMIEs, and belongingness. | When healthcare workers are exposed to more PMIEs, they also experience moral injury symptoms, which is associated with anxiety and depression. The relation between PMIE and depression and anxiety is mediated via moral injury symptoms and moderated by thwarted belonging. |

| Brown, Proudfoot, Mayat, and Finn 2021 [46] United Kingdom | To explore, “how do newly qualified doctors experience transition from medical school to practice” and “moral injury during transition”? | n = 7 New doctors (first 4 years) with an age range of 24–29 years, predominantly female, and who recently experienced a transition (<2 years). Purposive Sampling | Qualitative Hermeneutic Phenomenology [64]. Semi-Structured Interviews Thematic Analysis using an Interpretivist Paradigm [64,65,66]. Multiple and Multidimensional Transitions (MMT) Theory [67]. | Moral Injury (Shay’s Definition) Transitional Experiences | Themes: The nature of transition to practice. The influence of community. The influence of personal beliefs and values. The impact of the unrealistic undergraduate experience. | Transition to practice was viewed negatively due to the lack of interpersonal support in 4-month rotations. Participants relied on the ethics of caring values to cope, but this in itself is troublesome and predisposes to moral injury. |

| Chandrabhatla, Asgedom, Gaudiano, de Avila, Roach, Venkatesan, Weinstein, and Younossi 2022 [49] United States | To examine the relationship between burnout, second victim experiences, and moral injury experiences before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among hospitalists. | n = 81 Hospitalists between the ages of 20 and 40, with a stable partner/married, have children, and the majority of their work was clinical. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Cross-sectional comparison Independent sample t-test No use of theory | Moral Injury MIES Burnout Mini Z Burnout Survey Second Victim Experiences Second Victim Experience and Support Tool Well-being Flourishing Scale Satisfaction with Life Scale Work Wellbeing Work Wellbeing Scale | Burnout levels reported were the same across pre COVID-19 and during COVID-19. An increase in reporting of second victim experiences during COVID-19, whether the hospitalist experiences burnout or not. | Moral injury was named as a predictive variable of burnout during COVID-19 in this study. During the pandemic, there was a higher rate of moral injury amongst burned out hospitalists. |

| Dale, Cuffe, Sambuco, Guastello, Leon, Nunez, Bhullar, Allen, and Mathews 2021 [47] United States | This study investigated the occurrence that HCPs were experiencing MI, whether the experience of MI was related to co-occurring psychiatric symptomatology, self/others MI, and burnout. | n = 265 Majority white females with a mean age of 37.6 years old. Worked in a large city, have a college degree, and married or in a long-term relationship. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Longitudinal Logistic Regressions Multilinear regression Multilevel modeling No use of theory | Moral Injury MIES Healthcare Morally Distressing Experiences 4-study related questions Current Psychiatric Symptomatology PHQ-9 GAD-7 PTSD Checklist-5 Workplace Burnout Professional Fulfillment Index (PFI) | Notably, longitudinally, self-moral injury was most impactful on experiences of burnout, and others moral injury was level influential on burnout. Higher levels of self-moral injury were correlated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and other moral injury was only associated with depression. | When a healthcare worker conducts a moral injury themselves, they are most at risk for experiencing burnout. While witnessing others do things that healthcare workers find morally injurious can cause some depression, it is the individual moral injury that contributes to anxiety and PTSD. |

| Kreh, Brancaleoni, Magalini, Chieffo, Flad, Ellebrecht, and Juen 2021 [18] Austria and Italy | To develop basic hypotheses regarding resilience and stress experiences of healthcare workers in the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. | n = 13 Healthcare workers (psychologists, physicians, and nurses) between the ages of 26 and 40, mostly female, with at least 5 or 10 years of experience for staff and clinicians, respectively. Convenience Sampling | Qualitative Grounded Theory Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups Thematic Analysis [68]. No use of theory | Moral Injury (Shay’s Definition; Litz’s Definition) Psychological Safety Stress Institutional Support Resilience | Themes: Fear, guilt feelings, frustration, loss of trust, and exhaustion Casual factors: rapidly evolving situations with high uncertainty Stressors Resilience factors 3 developed hypotheses | Stress, power imbalance, and inability to separate home from work were all named as precursors to moral injury. Then, moral injury could result in poor mental health. |

| Levi-Belz and Zerach 2022 [50] Israel | To highlight the emotional burden (depression and anxiety) among healthcare workers during COVID-19, and to further understand the direct and indirect role of PMIEs as well as the mediating role of stress and moral injury symptoms on depression and anxiety. | n = 296 Majority female, Israeli-born, and married. Mean age of 40.28 years, and included nurses, doctors, social and psychological care workers, and clinical support workers who mostly worked in hospitals, with an average 12 years of experience. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Cross-sectional Pearson’s Correlations Structured Equation Modeling No use of theory | Moral Injury (Litz’s Definition) MISS-HP PMIE MIES Depression PHQ-9 Anxiety GAD-7 Perceived Stress Perceived Stress Scale | PMIEs were significantly positively correlated with depression and anxiety. Stress and MI were also found to be significant mediating variables between PMIE and anxiety and depression. The full model explained 63% variance in depression and 57% variance in anxiety. | This study highlights the relationship between moral injury and stress as well as moral injury increasing anxiety and depression. |

| Murray, Krahé, and Goodsman 2018 [19] United Kingdom | To determine whether the concept of moral injury resonated with medical students working in emergency medicine and what might mitigate that injury for them. | n = 5 Medical students in prehospital care. Convenience Sampling —Sampled using critical case sampling | Qualitative Phenomenological Structured Interviews Focus Groups Thematic Analysis [61] No use of theory, names need for theoretical framing | Moral Injury (Shay’s Definition; Litz’s Definition) Trauma Exposure Social Support | Themes: What is Seen on Scene Material versus Human Resources The Complexity of Debrief | Moral injury acts as a reaction to witnessing trauma (but does not qualify as PTSD). Then, experiencing moral injury can lead to other wellbeing outcomes. Social supports and debriefing traumatic events are protective factors to reduce experiences of moral injury. |

| Hines, Chin, Glick, and Wickwire, 2021 [16] United States | The purpose of the project was to quantify experiences of moral injury anddistress in HCWs during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic response. | n = 96 Majority female attending physicians with a mean age of 41 years old and an average of 14 years of experience in healthcare. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Prospective Longitudinal Survey Design Descriptive Analysis Paired t-test Hierarchical Linear Modeling No use of theory | Moral Injury (Litz’s Definition) MIES Resilience Resilience Scale Distress IES-R | In the final model, stressful work environment was significantly associated with moral injury, while supportive work environment was nearly significantly associated with lower moral injury. | Stress and support are both related to moral injury, and stress was identified as a predictor to moral injury. |

| Litam and Balkin 2020 [51] United States | To understand the extent to which healthcare workers experience moral injury while working in a pandemic. | n = 109 Majority white, female physicians and nurses, with an average age of 38 years old and an average of 12 years in healthcare. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey Design Descriptive, correlational, and Multiple regression analyses No use of theory | Moral Injury (Litz’s Definition) MIES Professional Quality of Life PROQOL: -Compassion Satisfaction (CS) -Burnout -Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) | STS was significantly associated with moral injury. Given the higher correlation between secondary traumatic stress and moral injury, a limited contribution of burnout was identified within the model, so burnout was removed. | STS was shown to significantly contribute to moral injury as a predictor. Burnout showed no association to moral injury, and CS was not significantly associated with moral injury. |

| Mantri, Song, Lawson, Berger, and Koenig 2021a [52] United States | To (a) characterize the changes in HP moral injury wrought by the pandemic over the course of 2020 and (b) identify potential predictors of moral injury amongst HPs. | n = 1831 Majority white, female, Christian, between the ages of 35–44, nurses and doctors, who are married. Snowball Sampling | Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey Design Descriptive Student’s t-test Pearson’s Correlations Logistic Regression No use of theory | Moral Injury (Shay’s Definition) MISS-HP Religiosity Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) Burnout Abbreviated MBI | Results indicated that significant negative predictors of MISS-HP included ages of more than 55 years old, greater religiosity, direct experience with patients with COVID-19, divorced, and non-nursing professions. | Moral injury is a parallel construct to burnout. Moral injury has been suggested as a precursor to burnout [52], and it is possible that burnout rates will continue to increase as a lagging marker of ongoing moral strain. Personal identity factors impact moral injury. |

| Mantri, Lawson, Zhizhong, and Koenig 2021b [53] United States | To a) examine the prevalence of moral injury symptoms causing impairments in family, social, or occupational functioningand b) identify predictors of MI symptoms in bivariate and multivariate analyses. | n = 181 Majority white, male, physicians, with a majority of participants under the age of 55, who are Christian. Snowball Sampling | Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey Design Descriptive ANOVA Student’s t-test Pearson Correlations No use of theory | Moral Injury (Shay’s Definition; Litz’s Definition) MISS-HP Clinical Characteristics Religious Characteristics BIAC Depression PHQ-9 Anxiety GAD-7 Burnout MBI | Moral injury symptoms were significantly more common among individuals who were more depressed, who were more anxious, or, especially, who indicated more burnout symptoms. In the final model, the strongest predictor of MI symptoms was burnout, followed by commission of medical errors in the past month, and religiosity at a trend level. | Moral injury is correlated with individuals with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and burnout. Committing medical errors, younger age, lower religiosity, and fewer years in practice were all significant predictors of moral injury. Moral injury mediates the relationship between experiencing transgressing moral code and the clinical outcomes. |

| Morris, Webb, and Devlin 2022 [54] United Kingdom | To explore if healthcare providers in psychiatric settings are exposed to PMIEs, what the relationship between PMIEs and wellbeing are, and what the impact of COVID-19 is on PMIEs and wellbeing. | n = 237 Majority of participants were female, white British, between 21 and 30, and unregistered nurses. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Cross-sectional Survey Design Spearman Rank-Order Correlations Bootstrapped Regressions No use of theory | Moral Injury/PMIEs (Litz’s Definition) MIES Wellbeing (Subscales: Burnout, Secondary Trauma, Compassion Satisfaction) ProQOL-5 | Moral injury has significant positive associations with burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and significant negative associations with compassion satisfaction. | Moral injury was predictive of higher secondary trauma and burnout as well as lower self-compassion amongst healthcare workers. |

| Ulusoy and Çelik 2021 [55] Turkey | To determine burnout levels and possible related psychological processes such as psychological flexibility, moral injury, and values among healthcare workers after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. | n = 124 The sample was majority female doctors with a mean age of 33.3 years old. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Cross-sectional Survey Design Correlation Analysis Multiple Linear Regression No use of theory | Moral Injury (Litz’s Definition) MIES Psychological Flexibility Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II Burnout MBI Depression and Anxiety Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 Values Valuing Questionnaire | Depression and anxiety were the only significant predictors of emotional exhaustion. Moral injury was the only significant predictor of depersonalization. Moral injury, days worked during COVID-19, and value obstruction were the significant predictors for personal accomplishment. | This study demonstrates associations between moral injury and burnout, specifically moral injury as a predictor of depersonalization and personal accomplishment within burnout. |

| Zerach and Levi-Belz 2021 [56] Israel | The objectives of this study were to examine patterns of exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) among HSCWs and their associations with MI, mental health outcomes and psychological correlates. | n = 296 Majority female, Israeli-born, and married, with a mean age of 40.28 years, and included nurses, doctors, social and psychological care workers, and clinical support workers who mostly worked in hospitals. Convenience Sampling | Quantitative Cross-sectional survey Design Latent Class Analysis No use of theory | Moral Injury MISS-HP Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs) MIES Depression PHQ-9 Self-Criticism Factor from Depressive Experiences Questionnaire Trauma International Trauma Questionnaire for PTSD and C-PTSD Self-Compassion Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form | Participants who had high exposure or betrayal exposure to moral injury experienced more PTSD and moral injury symptoms than those with minimal exposure. Those in the high exposure group also had more depressive symptoms. Additionally, those in the high exposure and betrayal only exposure groups had higher rates of self-criticism and lower self-compassion. | This study highlighted the relationship between moral injury and trauma (PTSD), mental health (depression), self-criticism and low self-compassion. |

| Zhizhong, Al Zaben, Koenig, and Ding 2021 [57] China | To examine the relationship between spirituality, moral injury, and mental health among physicians and nursesin mainland China during the COVID-19 pandemic. | n = 3006 Majority Han, female, doctors, with bachelor’s degree, married, and not affiliated with religion, with an average age of 35 years old, with an average of 12 years of practice. Snowball Sampling | Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey Design Descriptive Pearson’s Correlations Students t-test ANOVA Hierarchical Linear Modeling No use of theory | Moral Injury (Litz’s Definition) MISS-HP Spirituality Depression PHQ-9 Anxiety GAD-7 | Spirituality was positively correlated with moral injury, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms) after controlling sociodemographic variables. | Moral injury is correlated with mental illness. Those with higher spirituality were associated with experiencing higher moral injury. Moral injury was a mediating variable but was not a moderating variable between spirituality and depression/anxiety. |

| Zhizhong, Koenig, Yan, Jing, Mu, Hongyu, and Guangtian 2020 [58] China | To assess the psychometric properties of the 10-item Moral Injury Symptoms Scale-Health Professional (MISS-HP) among healthcare professionals in China. | n = 3006 Majority Han, female, doctors, with bachelor’s degree, married, and not affiliated with religion, with an average age of 35 years old, with an average of 12 years of practice. Snowball Sampling | Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey Design Pearson’s Correlations Students t-test ANOVA No use of theory | Moral Injury (Litz’s Definition) MISS-HP Spirituality Depression PHQ-9 Anxiety GAD-7 Well-being Secure Flourish Index (SFI) Burnout MBI-HSMP | Moral injury had a small significant inverse correlation with personal accomplishment and a significant moderate inverse association with SFI. Otherwise, moral injury had a significant moderate positive association with the remaining constructs: PHQ-9, GAD-7, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization. | Moral injury is found in increasingly stressed healthcare professionals, and moral injury is correlated with depression, anxiety, burnout (all three subconstructs), and flourishing. |

3.4. Quantitative Studies Summary

3.5. Personal Wellbeing

3.6. Professional Wellbeing

3.7. Use of Theory

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Framing

4.2. Power as a Measured Construct

4.3. Consequences of Moral Injury for Healthcare Workers

4.4. Contextualizing Moral Injury within Wellbeing

4.5. Burnout

4.6. Trauma

4.7. Mental Health

4.8. Spirituality/Religiosity

4.9. Measuring Moral Injury

4.10. Synthesis of the Literature

4.11. Future Directions in Research

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Census Bureau. 22 Million Employed in Health Care Fight Against COVID-19. Census.gov. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/who-are-our-health-care-workers.html (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Elsevier. Clinicians of the Future: A 2022 Report; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1242490/Clinician-of-the-future-report-online.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Cartolovni, A.; Stolt, M.; Scott, P.; Suhonen, R. Moral Injury in Healthcare Professionals: A Scoping Review and Discussion. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Burned-Out Physician. In The Burned Out Physician: Managing the Stress and Reducing the Errors; Kello, J.E., Allen, J.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabarkapa, S.; Nadjidai, S.E.; Murgier, J.; Ng, C.H. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 and Other Viral Epidemics on Frontline Healthcare Workers and Ways to Address It: A Rapid Systematic Review. Brain Behav. Immun.—Health 2020, 8, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Utility of a Brief Screening Tool to Identify Physicians in Distress. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wee, K.Z.; Lai, A.Y. Work Engagement and Patient Quality of Care: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, S.E. The Web of Silence: A Qualitative Case Study of Early Intervention and Support for Healthcare Workers with Mental Ill-Health. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, S.J.; Ranjalkar, J.; Chandy, S.S. Collateral Effects and Ethical Challenges in Healthcare Due to COVID-19—A Dire Need to Support Healthcare Workers and Systems. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, N.; Harrex, W.; Rees, M.; Willis, K.; Bennett, C.M. COVID-19 Infection and the Broader Impacts of the Pandemic on Healthcare Workers. Respirology 2022, 27, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J. Moral Injury. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2014, 31, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, B.T.; Kerig, P.K. Introduction to the Special Issue on Moral Injury: Conceptual Challenges, Methodological Issues, and Clinical Applications. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, P.-L.; Kreh, A.; Kulcar, V.; Lieber, A.; Juen, B. A Scoping Review of Moral Stressors, Moral Distress and Moral Injury in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. IJERPH 2022, 19, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, E. Understanding the Effect of Moral Transgressions in the Helping Professions: In Search of Conceptual Clarity. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2019, 93, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAninch, A. Moral distress, moral injury, and moral luck. Am. J. Bioeth. 2016, 16, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, S.E.; Chin, K.H.; Glick, D.R.; Wickwire, E.M. Trends in Moral Injury, Distress, and Resilience Factors among Healthcare Workers at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hert, S. Burnout in Healthcare Workers: Prevalence, Impact and Preventative Strategies. Local Reg. Anesth. 2020, 13, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreh, A.; Brancaleoni, R.; Magalini, S.; Chieffo, D.; Flad, B.; Ellebrecht, N.; Juen, B. Ethical and Psychosocial Considerations for Hospital Personnel in the COVID-19 Crisis: Moral Injury and Resilience. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, E.; Krahe, C.; Goodsman, D. Are Medical Students in Prehospital Care at Risk of Moral Injury? Emerg. Med. J. 2018, 35, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalera, C. COVID-19 Psychological Implications: The Role of Shame and Guilt. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 571828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândea, D.-M.; Szentagotai-Tătar, A. Shame-Proneness, Guilt-Proneness and Anxiety Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 58, 78–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Medicine. Taking Action against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being; The National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, P.; Devkota, N.; Dahal, M.; Paudel, K.; Joshi, D. Mental health impacts among health workers during COVID-19 in a low resource setting: A cross-sectional survey from Nepal. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine, A.; Ruotsalainen, J.H.; Serra, C.; Verbeek, J.H. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 4, CD002892. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Li, H.; Zhu, W.; Lin, S.; Chai, W.; Wang, X. Effect of work stressors, personal strain, and coping resources on burnout in Chinese medical professionals: A structural equation model. Ind. Health 2012, 50, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Bruinvels, D.; FringsDresen, M. Psychosocial work environment and stress related disorders, a systematic review. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health—A meta-analytic review. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2006, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Worker Wellness: A Scoping Review. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.-A.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’malley, C.M. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, C.G.; Sabina, S.; Tumolo, M.R.; Bodini, A.; Ponzini, G.; Sabato, E.; Mincarone, P. Burnout Among Healthcare Workers in the COVID 19 Era: A Review of the Existing Literature. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 750529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health America (MHA). The Mental Health of Healthcare Workers in COVID-19: Survey Results; Mental Health America: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Fang, Y.; Guan, Z.; Fan, B.; Kong, J.; Yao, Z.; Liu, X.; Fuller, C.J.; Susser, E.; Lu, J.; et al. The Psychological Impact of the SARS Epidemic on Hospital Employees in China: Exposure, Risk Perception, and Altruistic Acceptance of Risk. Can. J. Psychiatry. Rev. Can. De Psychiatr. 2009, 54, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmoe, M.C.; Chapman, M.B.; Gold, J.A.; Giedinghagen, A.M. Physician Suicide: A Call to Action. Mo. Med. 2019, 116, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Watt, I.; Tsipa, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P): Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, A.; Cherry, M.; Dickson, R. Doing a Systematic Review: A Student’s Guide; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: York, UK, 2009; Available online: https://www.york.ac.uk/crd/guidance/ (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Booth, A. Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice. Libr. Hi Tech 2006, 24, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 5.0.0 [updated February 2008]; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Canoga Park, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies. JBI Evid. Synth. 2014, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.W. Walking Together in Exile: Medical Moral Injury and the Clinical Chaplain. J. Pastor. Care Couns. 2020, 74, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, J.; Watsford, C.; Scholz, B. Psychosocial Impacts of Training to Provide Professional Help: Harm and Growth. Trauma 2020, 24, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.L.; Proudfoot, A.; Mayat, N.Y.; Finn, G.M. A Phenomenological Study of New Doctors’ Transition to Practice, Utilising Participant-Voiced Poetry. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2021, 26, 1229–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, L.P.; Cuffe, S.P.; Sambuco, N.; Guastello, A.D.; Leon, K.G.; Nunez, L.V.; Bhullar, A.; Allen, B.R.; Mathews, C.A. Morally Distressing Experiences, Moral Injury, and Burnout in Florida Healthcare Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benatov, J.; Zerach, G.; Levi-Belz, Y. Moral Injury, Depression, and Anxiety Symptoms among Health and Social Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Moderating Role of Belongingness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrabhatla, T.; Asgedom, H.; Gaudiano, Z.P.; de Avila, L.; Roach, K.L.; Venkatesan, C.; Weinstein, A.A.; Younossi, Z.M. Second Victim Experiences and Moral Injury as Predictors of Hospitalist Burnout before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Zerach, G. The Wounded Helper: Moral Injury Contributes to Depression and Anxiety among Israeli Health and Social Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anxiety Stress Coping 2022, 35, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litam, S.D.A.; Balkin, R.S. Moral Injury in Health-Care Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic. Traumatology 2020, 27, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantri, S.; Song, Y.; Lawson, J.; Berger, E.; Koenig, H. Moral Injury and Burnout in Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 209, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantri, S.; Lawson, J.; Wang, Z.; Koenig, H. Prevalence and Predictors of Moral Injury Symptoms in Health Care Professionals. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 209, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.J.; Webb, E.L.; Devlin, P. Moral Injury in Secure Mental Healthcare Part II: Experiences of Potentially Morally Injurious Events and Their Relationship to Wellbeing in Health Professionals in Secure Services. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2022, 33, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, S.; Celik, Z. The Silent Cry of Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study on Levels and Determinants of Burnout among Healthcare Workers after First Year of the Pandemic in Turkey. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 32, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerach, G.; Levi-Belz, Y. Moral Injury and Mental Health Outcomes among Israeli Health and Social Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Class Analysis Approach. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1945749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhizhong, W.; Al Zaben, F.; Koenig, H.; Ding, Y. Spirituality, Moral Injury and Mental Health among Chinese Health Professionals. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhizhong, W.; Koenig, H.G.; Yan, T.; Jing, W.; Mu, S.; Hongyu, L.; Guangtian, L. Psychometric Properties of the Moral Injury Symptom Scale among Chinese Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.J.; Purcell, N.; Burkman, K.; Litz, B.T.; Bryan, C.J.; Schmitz, M.; Villierme, C.; Walsh, J.; Maguen, S. Moral Injury: An Integrative Review. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G.; Ames, D.; Büssing, A. Editorial: Screening for and Treatment of Moral Injury in Veterans/Active Duty Military With PTSD. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2016, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, C.A. Establishing Evidence for Strengths-Based Interventions? Reflections from Social Work’s Research Conference. Soc. Work. 2009, 54, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Jarman, M.; Osborn, M. Doing Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In Qualitative Health Psychology: Theories and Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1999; pp. 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A.; Collin, A. Introduction: Constructivism and Social Constructionism in the Career Field. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, V.; Smith, J.A. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In Handbook of Qualitative Psychology, 2nd ed.; Sage Publishing: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.; Jindal-Snape, D.; Morrison, J.; Muldoon, J.; Needham, G.; Siebert, S.; Rees, C. Multiple and Multidimensional Transitions from Trainee to Trained Doctor: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study in the UK. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Aldine: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, W.P.; Marino Carper, T.L.; Mills, M.A.; Au, T.; Goldsmith, A.; Litz, B.T. Psychometric Evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantri, S.; Lawson, J.; Wang, Z.; Koenig, H. Identifying Moral Injury in Healthcare Professionals: The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-HP. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2323–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, G.L. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. New Insights into Burnout and Health Care: Strategies for Improving Civility and Alleviating Burnout. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reamer, F.G. Moral Injury in Social Work: Responses, Prevention, and Advocacy. Fam. Soc. 2021, 103, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; West, C.; Zhao, X.; Novotny, P.; Kolars, J.; Habermann, T.; Sloan, J. Relationship Between Increased Personal Well-Being and Enhanced Empathy Among Internal Medicine Residents. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinkerson, J.D. Defining and assessing moral injury: A syndrome perspective. Traumatology 2016, 22, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.; Leiter, M. Maslach Burnout Inventory, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christina-Maslach/publication/277816643_The_Maslach_Burnout_Inventory_Manual/links/5574dbd708aeb6d8c01946d7/The-Maslach-Burnout-Inventory-Manual.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Kopacz, M.S.; Ames, D.; Koenig, H.G. It’s Time to Talk about Physician Burnout and Moral Injury. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, E28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Satele, D.; Shanafelt, T. Ability of a 9-Item Well-Being Index to Identify Distress and Stratify Quality of Life in US Workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haefner, J. Self-Care for Health Professionals During Coronavirus Disease 2019 Crisis. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, F.; Clatty, A. Self-Care Strategies in Response to Nurses’ Moral Injury during COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thibodeau, P.S.; Nash, A.; Greenfield, J.C.; Bellamy, J.L. The Association of Moral Injury and Healthcare Clinicians’ Wellbeing: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136300

Thibodeau PS, Nash A, Greenfield JC, Bellamy JL. The Association of Moral Injury and Healthcare Clinicians’ Wellbeing: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(13):6300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136300

Chicago/Turabian StyleThibodeau, Pari Shah, Aela Nash, Jennifer C. Greenfield, and Jennifer L. Bellamy. 2023. "The Association of Moral Injury and Healthcare Clinicians’ Wellbeing: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 13: 6300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136300

APA StyleThibodeau, P. S., Nash, A., Greenfield, J. C., & Bellamy, J. L. (2023). The Association of Moral Injury and Healthcare Clinicians’ Wellbeing: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136300