Use of Intersectionality Theory in Interventional Health Research in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Review Aim

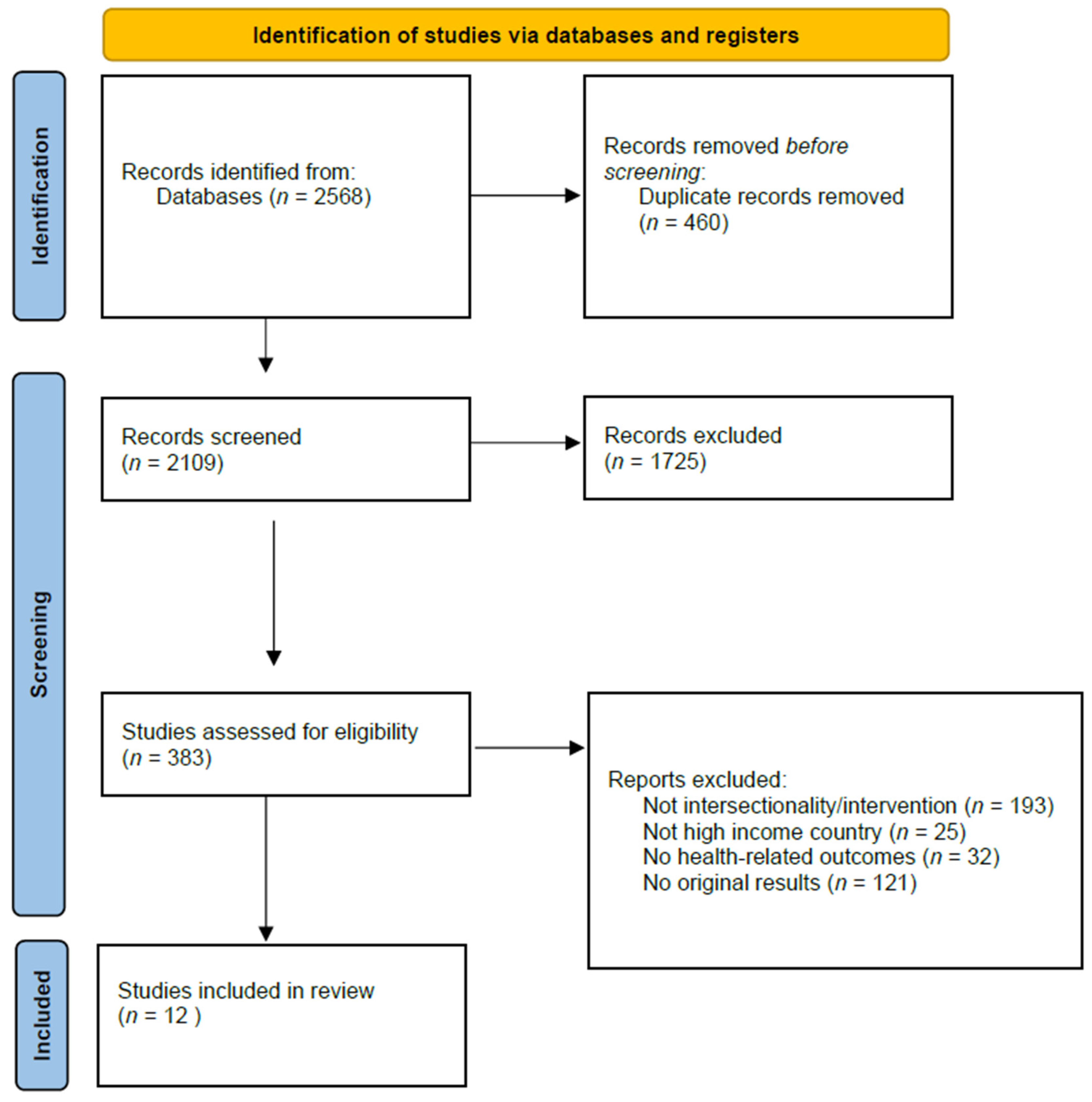

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Synthesis of the Results

2.6. Selection Process

3. Results

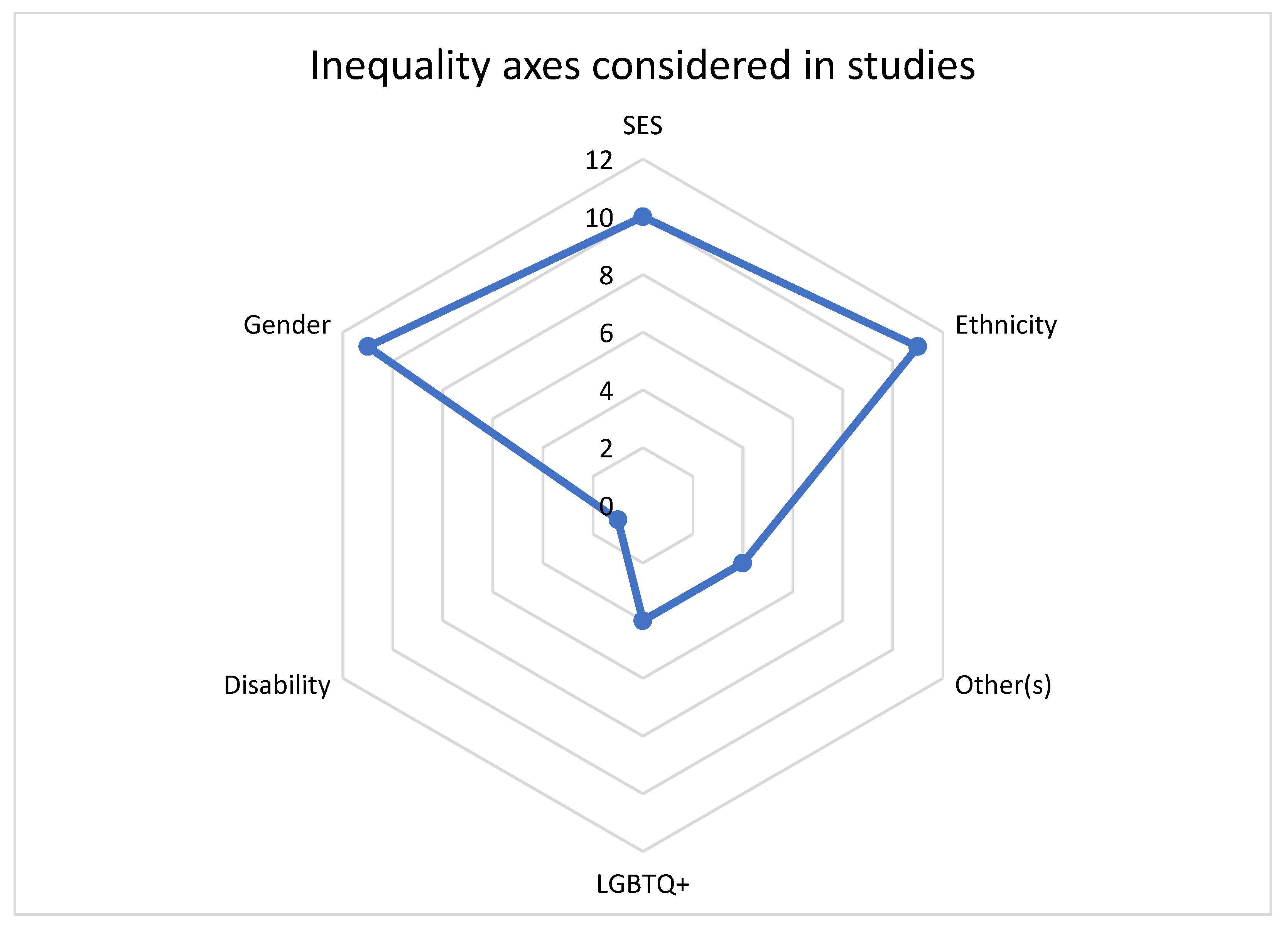

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.1.1. Use of Intersectionality to Analyse Impacts of Interventions (Eight Studies)

3.1.2. Intersectionality as a Tool to Design Interventions (Four Studies)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Strategy–Medline via Web of Science. Date: 11 May 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocks | Search terms | Results | |

| # 7 | #6 AND #1 | 1455 | |

| Indexes = MEDLINE Timespan = All years | |||

| # 6 | #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 | 14,113,133 | |

| Indexes = MEDLINE Timespan = All years | |||

| # 5 | Interventions | TS = ((Public Health Practices) OR (Community health services) OR (health care rationing) OR (Healthy People Program) OR (capacity building) OR (health facilities) OR (health personnel) OR (health NEAR/2 promotion) OR (health services) OR (health care reform) OR (health plan implementation) OR (health planning technical assistance) OR (health NEAR priorities) OR (health resources) OR (national health programs) OR ((regional OR local) NEAR (public health)) OR (Preventive Health Services) OR (health NEAR education)) | 1,332,906 |

| Indexes = MEDLINE Timespan = All years | |||

| # 4 | Interventions | TS = ((intervention* OR program* OR strateg* OR quasi-experimental OR evaluat* OR evidence OR assessment OR effectiveness OR ‘health survey’ OR trial OR utilization OR access*) OR (quasi-experimental OR random$ OR ‘health survey’ OR “longitudinal study”) OR (comparative OR control* OR prospective OR evaluation OR blind* OR effective*)) | 13,749,807 |

| Indexes = MEDLINE Timespan = All years | |||

| # 3 | Interventions | MH = (Public Health Practices OR Community health services OR health care rationing OR Healthy People Program OR capacity building OR health facilities OR health personnel OR health promotion OR health services OR health care reform OR health plan implementation OR health planning technical assistance OR health priorities OR health resources OR national health programs OR regional health planning OR Preventive Health Services OR health education) | 352,501 |

| Indexes = MEDLINE Timespan = All years | |||

| # 2 | Interventions | MH = (clinical trials OR feasibility studies OR intervention studies OR comparative studies OR evaluation studies OR Evidence-Based Practice) | 83,140 |

| Indexes = MEDLINE Timespan = All years | |||

| # 1 | Intersectionality | TS = (intersectional*) | 2099 |

| Indexes = MEDLINE Timespan = All years |

Appendix B

| Author(s) | Country | Target Population | Health Issue(s) | Intervention | Intersectionality Framework | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gleeson, Herring, and Bayley (2020) [26] | UK (London-based) | Polish migrants and professionals | Alcohol misuse | Health promotion | The analysis has attempted to incorporate the experiences of migration, gender, alcohol use and social class to give a broad understanding of pathways into, through and beyond alcohol treatment. | The findings suggest a need for services to address the unique service needs of Polish (and potentially other migrant) women, including additional social stigma, social attitudes toward women within minority communities surrounding substance use and challenges to engaging with treatment. The professionals highlighted Polish migrant women’s likelihood of being dependent on a male partner both in terms of financial security and access to social networks. The multiple references from professionals relating to the interaction between alcohol use and domestic violence for this group of women also suggests a need for treatment services to be aware of the additional negative experiences of women and seek ways to ensure they are addressed within treatment programmes. |

| Liu et al. (2016), [25] | USA, UK, Australia, New Zealand and Norway | Researchers | Smoking cessation, increasing physical activity and healthy eating | Health promotion | An intersectional perspective in this study highlights both the mutually constitutive positive and negative effects these factors have on the social identities of members of ethnic minority populations, and their health practices and outcomes. | Findings include (i) the intersections of ethnicity and demographic variables such as age and gender highlight the different ways in which people interact, interpret and participate in adapted interventions; (ii) the representational elements of ethnicity such as ancestry or religion are more complexly lived than they are defined in adapted interventions; (iii) the contextual experiences surrounding ethnicity considerations shape the receptivity, durability and continuity of adapted interventions. |

| Lloyd, Rimes, and Hambrook (2021) [27] | UK (London-based) | Service users who had previously attended and completed the LGBQ Wellbeing Group were collated. | Mental health (anxiety and depression) | Mental health | Intersectional approaches are situated in the understanding that individual identities are built on multiple different layers relating to different aspects of our socially defined selves, such as gender, gender identity, sexuality, race/ethnicity, social class, etc. | Respondents reported that they found the CBT frame of the group useful, with the LGBQ focus experienced as particularly beneficial, often enhancing engagement with CBT concepts and tools. In addition to generic elements of group therapy that some found difficult, others reported that intragroup diversity, such as generational differences, could lead to a reduced sense of connection. Several suggestions for group improvement were made, including incorporating more diverse perspectives and examples in session content and focusing more on issues relating to intersectionality. |

| Medina-Perucha et al. (2019) [28] | UK | Women, over 18 years of age, and on/having received opioid substitution treatment | Drug abuse | Health promotion | Drug use-related stigma often overlaps with stigma associated with other interdependent social categories. Personal and social identity can actually be understood as multidimensional rather than the unidimensional product of a combination of personal attributes and belonging to certain social groups. An individual can experience multiple overlapping stigmas (intersectional stigma) that refer to associations between social identities and structural inequities. | Women’s narratives highlighted the intersection of stigma associated with distinct elements of women’s identities: (1) female gender, (2) drug use, (3) transactional sex, (4) homelessness and (5) sexual health status. Intersectionality theory and social identity theory are used to explain sexual health risks and disengagement from (sexual) health services among women on opioid substitution treatment (WOST). Intersectional stigma was related to a lack of female and male condom use and a lack of access to (sexual) health services. |

| Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar (2019) [29] | UK (England and Wales) | Single people, without dependents, aged between 18 and 24 | Housing, Physical safety and harassment, mental health and isolation | Housing | An intersectional framework attempts to take into consideration the ways in which people are multiply marginalized by different, but interlinked, social structures: such as class, racism, sexism, homophobia and ableism. | The analysis focuses on two key themes: physical safety and violence, followed by mental health and isolation. Ultimately, the paper examines whether housing welfare reform in Britain has resulted in placing already vulnerable people into potentially dangerous and unhealthy housing situations. |

| Stevens et al. (2018) [30] | USA | Pregnant and postpartum women | Perinatal mental health | Mental health treatment | Intersectionality attends to the interactive relationships among social factors such as race, ethnicity, education, partner status, income, geography and other factors that play a key role in perinatal mental health and adjustment to parenting. Viewed through this lens, perinatal women’s experiences as “socially vulnerable” are influenced by the complex interweaving of numerous possible factors. | Results showed high treatment engagement and effectiveness, with 65.9% of participants demonstrating reliable improvement in symptoms. African American and Hispanic/Latina patients had similar treatment outcomes compared to White patients, despite facing greater socio-economic disadvantages. Findings indicate that the treatment model may be a promising approach to reducing perinatal mental health disparities. |

| Morrow et al. (2020) [31] | Canada | Participants were Asian men living with or affected by mental illness and community leaders interested in stigma reduction and advocacy. | Mental health | Mental health | As an analytic framework, intersectionality helps to clarify the complex interactions between age and ableism, colonization and white supremacy, heteronormativity and hegemonic masculinity, xenophobia and neoliberalism. This paper use intersectionality to explore Asian men’s experiences of stigma and mental illness specifically to tease out the ways in which stigma of mental illness among Asian men is mediated by age, immigration experiences, sexual and gender identities, racism and racialization processes, normative expectations about masculinity and material inequality. | The data collected pre- and post-interventions revealed that men understand and experience stigma as inextricably linked to social location, specifically age, race, masculinity, ethnicity and time of migration. Our analysis also revealed that mental health stigma cannot be understood in isolation from other social and structural barriers. The application of intersectional frameworks must figure prominently in psychological research and in public health policies that seek to reduce mental health stigma in racialized communities. |

| Potter, Lam, Cinciripini, and Wetter (2021) [32] | USA | Participants were 424 male and female adult smokers | Smoking cessation | Health promotion | An intersectionality framework is useful for understanding how the interplay between multiple marginalized sociodemographic attributes may shape health inequities. This work highlights the importance of moving beyond prioritizing one category of social status as the basis for health inequities research. | Lower household income may be related to higher risk of smoking cessation failure. There were no significant interactions among race/ethnicity, gender and income in predicting relapse. Pairwise intersectional group differences suggested some groups may be at higher risk of relapse. Number of marginalized sociodemographic attributes did not predict relapse. |

| Kivlighan et al. (2019) [33] | USA | Clients who received one treatment episode of individual counselling | Mental health | Mental health | Intersectionality theory seeks to understand and promote the inseparable intersection of cultural identities. | Results indicated that therapists differed in their ability to produce changes in symptom-defined psychological distress as a function of clients’ intersecting identities of race-ethnicity and gender. |

| Bounds, Otwell, Melendez, Karnik, and Julion (2020) [34] | USA | Four focus groups were held with mainly African American youth. The majority of the experts were female and from an ethnic/racial minority background. | Reduce risk factors for sexual exploitation | Behavioural | Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that situates multiple microlevel experiences within macrolevel systems of privilege and oppression. Authors propose to take an intersectionality approach for the intervention with homeless youth and refine the content and approach to consider the layered risks associated with their age, race/ethnicity, sexual exploitation history, sexual/gender identity and family functioning. | Results from 29 youths and 11 providers indicate that there are unique considerations that must be taken into consideration while working with youth at risk of sexual exploitation to ensure effective service delivery and/or ethical research. Emergent themes included: setting the stage by building rapport and acknowledging experiences of structural violence, protect and hold which balances youth’s need for advocacy/support with their caregivers’ need for validation/understanding and walking the safety tightrope by assessing risks and safety planning. |

| David, Rowe, Staeheli, and Ponce (2015) [35] | USA | Homeless women | Mental health | Mental health | The framework of intersectionality highlights the ways in which interpersonal constructs—including race, class and gender—may coincide with social structures to dynamically shape an individual’s lived experience and sense of self. An intersectionality perspective maintains that social constructs including racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination can contribute to the development of an individual’s multiple marginalized personal identities. | Authors highlight four key principles that can optimize and promote the recovery outcomes of these women: (1) peer support, (2) flexible services and resources, (3) supportive program leadership and (4) gender-sensitive services provided by women. We provide case vignettes highlighting how each of these treatment principles fosters trust and helps to create safe psychological and physical spaces for women clients. |

| Kelly and Pich (2014) [36] | USA | Latinas with PTSD who experienced IPV | Mental health | Mental health | An intersectional approach frames the problem as one of power inequities at multiple levels–interpersonal, institutional and societal and multiple systems (race, ethnicity, gender/class). The integration of biomedical and intersectional approaches in this study meant that both the women’s PTSD systems and intersectional invisibility were acknowledged and addressed throughout the research study. | Significant reductions in PTSD and MDD and increased self-efficacy were sustained 6 months post-intervention. Culturally relevant mental health IPV interventions can be feasible and appropriate in women across ethnic groups. However, there were not significant impact on other outcomes such as quality of life. |

References

- Marmot, M. Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ 2020, 368, m693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentikelenis, Bambra & Forster. Health Inequalities in Europe. Setting the Stage for Progressive Policy Action. 2018. Available online: https://www.feps-europe.eu/resources/publications/629:health-inequalities-in-europe-setting-the-stage-for-progressive-policy-action.html (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Holman, D.; Salway, S.; Bell, A.; Beach, B.; Adebajo, A.; Ali, N.; Butt, J. Can intersectionality help with understanding and tackling health inequalities? Perspectives of professional stakeholders. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2021, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapilashrami, A.; Hankivsky, O. Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. Lancet 2018, 391, 2589–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Droit Soc. 2021, 108, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. Evolving intersectionality within public health: From analysis to action. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, O.; Grace, D.; Hunting, G.; Giesbrecht, M.; Fridkin, A.; Rudrum, S.; Ferlatte, O.; Clark, N. An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: Critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, P.H. Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowleg, L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, O. An Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Framework; Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy: Vancouver, BC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg, L. When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Mytton, O.; White, M.; Monsivais, P. Why Are Some Population Interventions for Diet and Obesity More Equitable and Effective Than Others? The Role of Individual Agency. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorenc, T.; Petticrew, M.; Welch, V.; Tugwell, P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauer, G.R.; Churchill, S.M.; Mahendran, M.; Walwyn, C.; Lizotte, D.; Villa-Rueda, A.A. Intersectionality in quantitative research: A systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard, E.; Fitzgerald, L.; Wigginton, B.; Mutch, A. Applying intersectionality theory in health promotion research and practice. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Evans, C.R.; Subramanian, S.V. Can intersectionality theory enrich population health research? Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, K.; Drey, N.; Gould, D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C. Placing intersectional inequalities in health. Health Place 2022, 75, 102761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.; George, A.; Morgan, R.; Poteat, T. 10 Best resources on … intersectionality with an emphasis on low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghasemi, E.; Majdzadeh, R.; Rajabi, F.; Vedadhir, A.; Negarandeh, R.; Jamshidi, E.; Takian, A.; Faraji, Z. Applying Intersectionality in designing and implementing health interventions: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.J.; Davidson, E.; Bhopal, R.; White, M.; Johnson, M.; Netto, G.; Sheikh, A. Adapting health promotion interventions for ethnic minority groups: A qualitative study. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, H.; Herring, R.; Bayley, M. Exploring gendered differences among polish migrants in the UK in problematic drinking and pathways into and through alcohol treatment. J. Ethn. Subst. Abuse. 2022, 21, 1120–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C.E.M.; Rimes, K.A.; Hambrook, D.G. LGBQ adults’ experiences of a CBT wellbeing group for anxiety and depression in an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Service: A qualitative service evaluation. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2021, 13, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Perucha, L.; Scott, J.; Chapman, S.; Barnett, J.; Dack, C.; Family, H. A qualitative study on intersectional stigma and sexual health among women on opioid substitution treatment in England: Implications for research, policy and practice. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982 2019, 222, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilkinson, E.; Ortega-Alcázar, I. Stranger danger? The intersectional impacts of shared housing on young people’s health & wellbeing. Health Place 2019, 60, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, N.R.; Heath, N.M.; Lillis, T.A.; McMinn, K.; Tirone, V.; Sha’ini, M. Examining the effectiveness of a coordinated perinatal mental health care model using an intersectional-feminist perspective. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M.; Bryson, S.; Lal, R.; Hoong, P.; Jiang, C.; Jordan, S.; Patel, N.B.; Guruge, S. Intersectionality as an Analytic Framework for Understanding the Experiences of Mental Health Stigma Among Racialized Men. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.N.; Lam, C.Y.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Wetter, D.W. Intersectionality and Smoking Cessation: Exploring Various Approaches for Understanding Health Inequities. Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2021, 23, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivlighan, D.M.; Hooley, I.W.; Bruno, M.G.; Ethington, L.L.; Keeton, P.M.; Schreier, B.A. Examining therapist effects in relation to clients’ race-ethnicity and gender: An intersectionality approach. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, D.T.; Otwell, C.H.; Melendez, A.; Karnik, N.S.; Julion, W.A. Adapting a family intervention to reduce risk factors for sexual exploitation. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- David, D.H.; Rowe, M.; Staeheli, M.; Ponce, A.N. Safety, Trust, and Treatment: Mental Health Service Delivery for Women Who Are Homeless. Women Ther. 2015, 38, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, U.A.; Pich, K. Community-based PTSD treatment for ethnically diverse women who experienced intimate partner violence: A feasibility study. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 35, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, L.; Lee, C. Intersectionality in quantitative health disparities research: A systematic review of challenges and limitations in empirical studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982 2021, 277, 113876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, A.-M. Intersectionality as a Normative and Empirical Paradigm. Polit. Gend. 2007, 3, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.; Walker, A. Understanding unequal ageing: Towards a synthesis of intersectionality and life course analyses. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, A.-M. Empirical Intersectionality: A Tale of Two Approaches. UC Irvine Law Rev. 2013, 3, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Fagrell Trygg, N.; Gustafsson, P.E.; Månsdotter, A. Languishing in the crossroad? A scoping review of intersectional inequalities in mental health. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitehead, M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hankivsky, O. Intersectionality 101. Ph. D. Thesis, The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU, Burnaby, Canada, April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FOR-EQUITY—Tools and Resources to Help Reduce Social and Health Inequalities. Available online: https://forequity.uk/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

| n = 12 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| USA | 6 | 50 |

| UK | 4 | 33.33 |

| Canada | 1 | 8.33 |

| Several countries | 1 | 8.33 |

| Year | ||

| 2021 | 2 | 16.66 |

| 2020 | 3 | 25 |

| 2019 | 3 | 25 |

| 2018 | 1 | 8.33 |

| 2017 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 1 | 8.33 |

| 2015 | 1 | 8.33 |

| 2014 | 1 | 8.33 |

| Research design | ||

| Qualitative | 6 | 50 |

| Quantitative | 3 | 25 |

| Mixed-method | 3 | 25 |

| Intersectionality use | ||

| Analysis | 8 | 66.66 |

| Design | 3 | 25 |

| Design/Analysis | 1 | 8.33 |

| Author(s) | Country | Health Topic | Sample Size | Intersectionality Use | Inequalities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SES | Ethnicity | Gender | LGBTQ+ | Disability | Other(s) | |||||

| Gleeson et al. (2020) QUAL [26] | UK | Alcohol misuse | 17 | Analysis | NA | |||||

| Liu et al. (2016), QUAL [25] | Various | Health promotion (Various) | 37 | Design | Age | |||||

| Lloyd et al. (2021) QUAL [27] | UK | Mental health | 18 | Analysis | Age | |||||

| Medina-Perucha et al. (2019) QUAL [28] | UK | Drug abuse | 20 | Analysis | Various | |||||

| Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar (2019) QUAL [29] | UK | Housing | 40 | Analysis | NA | |||||

| Stevens et al. (2018) QUAL [30] | USA | Mental health (perinatal) | 82 | Design /Analysis | NA | |||||

| Morrow et al. (2020) MIXED [31] | Canada | Mental health | 94 | Analysis | Age | |||||

| Potter et al. (2021) QUANT [32] | USA | Smoking cessation | 344 | Analysis | NA | |||||

| Kivlighan et al. (2019) MIXED [33] | USA | Mental health | 415 | Analysis | NA | |||||

| Bounds et al. (2020) MIXED [34] | USA | Risk for sexual exploitation | 40 | Design | NA | |||||

| David et al. (2015) QUANT [35] | USA | Mental health | 300 | Analysis | NA | |||||

| Kelly and Pich (2014) QUANT [36] | USA | Mental health | 27 | Design | NA | |||||

| 10 | 11 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tinner, L.; Holman, D.; Ejegi-Memeh, S.; Laverty, A.A. Use of Intersectionality Theory in Interventional Health Research in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146370

Tinner L, Holman D, Ejegi-Memeh S, Laverty AA. Use of Intersectionality Theory in Interventional Health Research in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(14):6370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146370

Chicago/Turabian StyleTinner, Laura, Daniel Holman, Stephanie Ejegi-Memeh, and Anthony A. Laverty. 2023. "Use of Intersectionality Theory in Interventional Health Research in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 14: 6370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146370

APA StyleTinner, L., Holman, D., Ejegi-Memeh, S., & Laverty, A. A. (2023). Use of Intersectionality Theory in Interventional Health Research in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(14), 6370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20146370